Hezbollah Leader Nasrallah

Hezbollah has long championed the armed confrontation against Israel in the Middle East. (ICG Report 2017, 2). Its image in the Arab street made a peak after the July war in 2006, and the group depicted this as its second victory after ending the Israeli occupation in southern Lebanon in May 2000 (Al-Manar 2017). The group’s leader Nasrallah became a highly popular name with his pictures being hung in several corners of the Arab street. In the spring of 2013, the group became an active part of the sectarian conflict in Syria where its enemy was not Israel but other Arabs and Muslims that filled the ranks of the opposition armed groups. Nevertheless, the group’s arguments about its Syrian entanglement convinced Lebanese Shi’as and its supporters from other Lebanese communities on the necessity of its deploying military force to Syria (Hu 2016). Overall, despite its resistance only against Israel for so many years, Hezbollah was able to develop a particular discourse to justify its use of force in Syria.

In this paper, I will present key aspects of Hezbollah’s view on the use of military force, focusing on the comparison of its resistance against Israel versus its armed intervention in Syria. What is a justified war from the group’s perspective? How does it change when facing a Muslim versus / and a non-Muslim enemy? What are the similarities and differences, if any, in Hezbollah’s legitimization discourse within the contexts of its wars against Israel versus its Syrian entanglement? In the remaining sections, Hezbollah’s conception of just war will be explored, comparing the discourses used in the cases of Israel and Syria. The paper will conclude with a discussion about the implications of the findings on the broader security dynamics in the Middle East.

Hezbollah and a Just War

From the perspective of Hezbollah, the primary reason that legitimizes taking up arms is resistance against injustice, oppression, and aggression (Heidekat 2010, 96).

This implies defending the lives, land and the dignity of the oppressed people when they are confronted with enemy aggression (Alahed 2011). It follows the example of Imam Hussein who did not surrender to the unjust demands of Yazid in the Karbala event, and it falls within the defensive mode of the al-Jihad al-Asghar, the Lesser Jihad. In Hezbollah’s view, any person suffering from oppression is worth protection and the group claims that it has been concerned about the security of all Lebanese people independent from their religions.

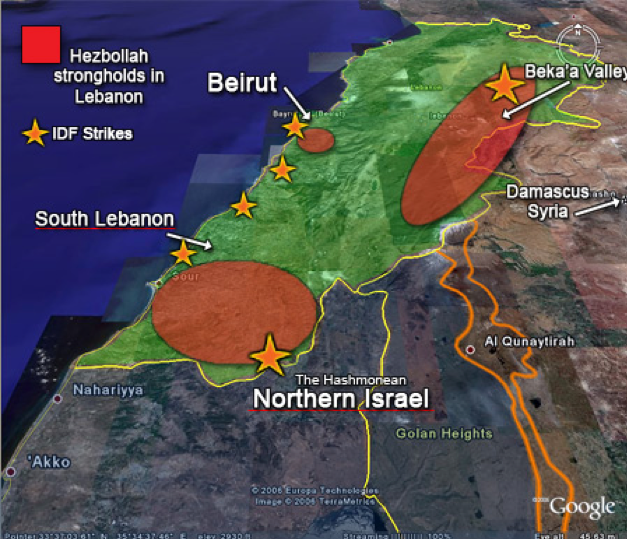

Source : (S. Israel, 2018)

In the case of Israel, Hezbollah fought against Israel’s forces until May 2000. Following the retreat of Israeli troops, the group carried on its armed resistance due to continuing Israeli presence in the Shebaa Farms which Hezbollah consider as Lebanese territory, to liberate Lebanese and Muslim prisoners who were jailed in Israel, and to respond to occasional air, land, and sea violations made by Israeli military (Alahed May 2014). Overall, the group contended that it was protecting the oppressed people of Lebanon from the aggressive actions of the oppressor, Israel, which, according to Hezbollah, enjoyed the support of the United States and other Western countries (New Manifesto 2009).

In the case of Syrian civil war, the group highlighted its armed struggle against the extremist groups. It argued that it was determined to pre-emptively protect Lebanese people from the atrocities of the terrorist entities such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL) (ICG Report 2014). For Hezbollah, its fight in Syria was once again resisting the hegemonic plans of the oppressor countries – the USA, Israel, and the West – which wanted to oppress the people of Syria by igniting ethnic and sectarian clashes and by seeking to fragment the country into several pieces (Alahed June 2014).

A major difference for Hezbollah in the cases of Israel and Syria is the fight against Muslims in the latter situation.

In Islam, jihad can also take place against Muslims when they demonstrate signs of apostasy or create dissension (Khadduri 1955, 75). Islamic jurists assert that when certain grievances lead to dissension amongst a Muslim population, reconciliation is the first option to deal with the problem before resorting to military jihad. For many jurists, “rebellion is worse than tyranny,” and dissension that may damage the unity of the Islamic community should be eschewed (Khadduri 1955, 77-79). This line of thinking was reflected in Hezbollah’s position on the Syrian conflict, and the group frequently emphasized the importance of maintaining the unity and territorial integrity in Syria (Alahed June 2014). Nasrallah blamed all the opposition armed groups for not heeding his calls to stop fighting against the properly functioning Syrian state, stating that there was “no horizon other than more bloodshed and more destruction of the country” in their aspirations to overthrow the Syrian regime by military force (Alahed June 2014).

Another difference in the context of Hezbollah’s involvement in the Syrian conflict was the group’s emphasis on the pre-emption arguments. The group did not limit itself to defensive battles along the border regions but also fought in different parts of Syria, claiming to be engaged in a pre-emptive war against ISIL and other extremist groups. In the available literature, it is not easy to find studies on the concept of pre-emption in Islam. Moreover, the distinction between the pre-emptive and preventive war in Islam is not that straightforward (Ssenyonjo 2012). Under this category, what is listed as a righteous ground for resorting to force is attacking first when there is a severe enemy threat. This can manifest itself when the enemy breaks a treaty or when its troops are seen in the preparation of war (IslamAwareness 2017). Was this exactly the case in Syria? For Hezbollah, the answer was positive because ISIL and Al Nusra Front were already at the border and their attacks in Lebanon were killing people.[1]

Overall, in Hezbollah’s messages to justify its taking up arms, defense, protection, and pre-emption were the main arguments emphasised by the group. This involved using force not only against non-Muslims but also against other Muslims that endanger the lives of ordinary people. In Syria, Hezbollah was not differentiating between the moderate or extremist factions among the opposition armed groups it was fighting against because for the group, they were all in complicity with the hegemonic powers. Moreover, they were not heeding Hezbollah’s calls to negotiate with the Syrian regime. As a result, from Hezbollah’s perspective, it was justified to use force against the Syrian opposition even this meant a shift of focus from its primary front against Israel.

Hezbollah’s Intentions against Israel and in Syria

In both its conflict against Israel and its military engagement in Syria, Hezbollah maintained that its weapons were not intended to harm people that belong to a particular religion or sect. It did not present its hostility against Israel to be driven out of an anti-Semitic stance (Das 2006, 32) because, for Hezbollah, Judaism is a divine religion and Jews are the “People of the Book” (Saad-Ghorayeb 2002, 168). Similarly, in the Syrian civil war, Hezbollah insisted that its fight was not against the Sunnis (Alahed November 2014). In both cases, Hezbollah contended that it was responding to enemy aggression, Israel in the former and extremist groups in the latter situation.

Since the group’s Syrian engagement was more controversial than its use of force against Israel in view of the Muslim populations, Nasrallah had to spend more energy to respond to accusations for acting with evil intentions in Syria. He appeared more frequently in the media to assert that it was, in fact, defending true Islam from the image ISIL and other extremist groups were representing (Pollak 2016, 12). He stressed that the battle in Syria was “a battle in defense of the Islam of Allah and his messenger Prophet Mohammed” and called on every Muslim – “scholars, journalists, authors” – to play their role while Hezbollah was using arms for this purpose (Alahed February 2015).

Hezbollah and the Iranian Dimension

Hezbollah’s links to Iran has a religious and a political dimension. The religious aspect is clearly presented by Hezbollah’s deputy secretary-general Naim Qassem in his book Hizbullah: The Story from Within (2005 and the 2010 edition with a new introduction). In this publication, Qassem lists three core pillars for the group: “Belief in Islam”, “Jihad” and attachment to the doctrine of “Wilayat al-Faqih” or the “Jurisdiction of the Jurist-Theologian”. The last one concerns Hezbollah’s acceptance of the al-Wali al-Faqih, the Supreme Shi’a religious leader of the time as the ultimate authority in sanctioning war decisions. The doctrine of Wilayat al-Faqih was introduced by Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini and came into practice with the Iranian revolution of 1979. Since then, Hezbollah has acknowledged and paid respect to the jurisdiction of Khomeini and his successor Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei (Daher 2007).

In its conflict against Israel, Hezbollah received the endorsements of both Imam Khomeini and Khamenei who did not hide their hostility toward Israel (Takeyh 2006). It is also likely that before planning an ambush operation and kidnapping Israel soldiers in July 2006 (operation “Truthful Pledge” as Hezbollah calls it), Hezbollah had the approval of Ayatollah Khamenei (Daher 2007). In the Syrian civil war, Nasrallah acknowledged receiving the consent of the al-Wali al-Faqih, saying that “We did not receive an order from His Eminence the Supreme Leader…. We have a legitimate permit, but we do not have an order: Go and fight or do so and so” (Alahed March 2016). In both cases, the religious authorization provided a critical layer to Hezbollah’s legitimacy claims and the group was able to mobilize several fighters in its military engagements.

The Iranian influence on Hezbollah is not limited to the religious dimension.

Iran played a critical role in Hezbollah’s establishment and for years, it has provided Hezbollah with weapons and funding (Devore 2012, 91). As a result, Hezbollah’s use of violence has mostly been in line with Iranian geopolitical interests despite Nasrallah’s continuous attempts to deny this. In his discourse, Nasrallah mostly downplays his organization’s ties to Iran and depicts Hezbollah as a Lebanese actor which is primarily concerned with the safety and security of the Lebanese people. He believes that Lebanon has many enemies and its security apparatus is not capable enough to face these challenges on its own. Therefore, from his perspective, Hezbollah should keep its weapons and use them when necessary (Alahed May 2006).

The Hezbollah-Iranian connection became much more obvious in Hezbollah’s decision to deploy fighters to a foreign soil, to Syria, as early as 2012 (Sullivan 2014). For many, Hezbollah’s fight in Syria was a move to sustain/expand Iranian influence in the Levant region by saving the friendly regime of Bashar al-Asad and by keeping the logistic channels open to Hezbollah (Sullivan 2014, ICG 2014). Moreover, Hezbollah has supported an Alawite regime and Alawism is considered as an offshoot of Shi’a Islam. Hezbollah denied these geopolitical and religious explanations and instead, highlighted its morally more acceptable reasons of defense and pre-emption against the extremist threat that was emanating from Syrian territory (Kizilkaya 2017).

Overall, when the Iranian dimension is concerned, there has not been a significant change for Hezbollah in relation to its recourse to violence. The group has closely coordinated its military actions with this country while continuously rejecting the claims for being an Iranian proxy. For the group, what has given Hezbollah the authority to retain and use weapons is the hostile security environment surrounding Lebanon, rather than the political and religious connections with the Iranian regime.

Hezbollah and Non-violent Alternatives to War

It is rather difficult to grasp Hezbollah’s views on the use of unarmed methods before engaging in conflicts. On the one hand, Nasrallah asserts that for Hezbollah, “fighting is not a hobby” and he stresses that it has been out of necessity, not a choice for the group to take up arms (Alahed March 2016). On the other hand, the group’s binary view of the events leads to an inclination towards resorting to force because the alternative is mostly perceived as a sign of weakness and running from responsibilities. Against Israel, Nasrallah presented the two available options as to whether resist and support the Palestinian cause or to accept “surrendering, normalization and submissiveness” (Alahed September 2009). In the context of Syria, Hezbollah also presented a binary situation in which the alternatives were either supporting the side of the extremists and their external funders or fighting alongside a regime which has been friendly to resistance movements that confronted Israel’s hegemony in the Middle East (Alahed May 2013).

Framing the conditions in this mode leaves limited or no room for negotiations and political dialogue in Hezbollah’s way of handling tensions. This was particularly the case in its conflicts against Israel because the group believed that diplomacy could only serve the interest of Israel and hence the only alternative was to use force against it (Qassem 2005, 149). The group declared its position against Israel in its first official manifesto of 1985 as “We recognize no treaty, cease-fire, peace agreement with Israel”, also stressing its determination to fight until Israel is obliterated. (Alagha 2006, 231). Over the years, there have been no signs of change in this hostile stance.

In the Syrian case, the situation was quite different because the fighting involved using weapons against other Muslims. In such conditions, the Quranic verse 49:9 dictates that when two Muslim groups or countries engage in a fight, a peaceful solution could be found to reconcile them, but if one of the sides continues to aggress upon the other, then force should be used until oppression is stopped (Alagha 2006, 231). Hezbollah’s messages concerning its reaction to the Syrian crisis at its initial stages followed a similar path that is ordered in this verse. Nasrallah claimed that Hezbollah contacted the opposition groups at the beginning of the crisis to facilitate dialogue between them and the regime (Alahed February 2012). According to him, these groups rejected a peaceful solution believing that they could easily topple the Syrian government and establish a new system in Syria. Nasrallah also blamed the regional Arab and Muslim countries which funded and supported these groups without giving a chance to a political solution. He said for many years, Arab countries engaged in dialogue with Israel but they did not show the same patience to Syria by arming the rebel groups in Syria. That is why in Nasrallah’s view, Hezbollah had to use weapons against these groups which did not leave any other alternative and which became a tool in the hegemonic plots to destroy the unity of Syria (Alahed February 2012).

Funeral of a Hezbollah fighter that died in Syria (Source: YaLibnan, 2018)

Overall, despite the presence of unarmed jihad as one of the modes of Hezbollah’s jihad concept, it could be argued that it was completely irrelevant in the case of the group’s conflict against Israel. In the Syrian civil war, despite Hezbollah’s emphasis on the steps it undertook to reconcile the conflicting parties, it did not take long for the group to be an active party in the conflict, which was once again legitimised by the binary formula of resist and shoulder the responsibility or avoid the duty and submit to hegemonic schemes.

Hezbollah and Victory

A notable aspect of Hezbollah’s discussion of victory in its armed confrontation against Israel is the emphasis attributed to the failures of the Israeli military in achieving its objectives. In a speech delivered in August 2016, Nasrallah gave the example of a favourite Israeli which says: “Let the army win” because it was presumed that the Israeli Army always achieves victory regardless of the mistakes in the political domain (Alahed, 13 August 2016). According to Nasrallah, this could have worked for decades in the Arab-Israeli conflicts but failed with the emergence of Hezbollah. Israel could not continue its occupation of Lebanon and had to withdraw in 2000, it could not destroy Hezbollah’s weapons arsenal in 2006, and it lost its status as being the singular deterrence power in the region (Alahed, 13 August 2016). For Nasrallah, it became difficult for Israel to start a war with Hezbollah owing to the group’s concrete accomplishments in the battlefield. In his view, whenever he promises to defeat Israel, it should never be perceived as empty rhetoric (Alahed, February 2013).

In the case of the Syrian civil war, Nasrallah argued that division of Syria would be a disaster for Syria, Lebanon, and the entire region. He contended that in such a scenario, it would be impossible to govern Syria because there will be multiple authorities (armed groups) establishing their control in tiny pieces of territory. (Alahed, June 2014). He believed that victory in Syria would entail maintaining the integrity of the Syrian state and expressed his confidence in his group’s capability to accomplish this objective (Alahed 25 May 2015). On the other side, in Nasrallah’s view, there were Saudi Arabia, Qatar and several regional and international players who wrongly assumed that the Syrian regime could be defeated against the opposition in a few months (Alahed March 2016). In his mind, Hezbollah acted with a prospect for success while the others were disappointed quickly owing to their incorrect assessment of the capabilities of the opposition armed groups (Alahed March 2016).

Conclusion

There is a wide literature dealing with Hezbollah’s origins, ideology, organizational structure, social activities, media, political thoughts, and behaviors. Its conflicts and military tactics are also subject of several publications. In this short article, I tried to focus on the way Hezbollah justified its violence, looking at the main similarities and the differences in the group’s conflicts against Israel versus its involvement in the Syrian conflict. The main common point in both cases was the influence of Iran which demonstrated itself in the religious green light received from the al-Wali al-Faqih (the Iranian Supreme Leader) and in the political plus economic backing provided by the Iranian government. In both situations, Hezbollah downplayed this Iranian influence and highlighted its commitment to Lebanese interests and to the well-being of the Lebanese community.

Different from its armed struggle against Israel, intervening in Syria introduced significant challenges for Hezbollah’s moral position in the Middle East. It involved a fight against a different enemy than Israel and it required shedding the blood of other Muslims that joined the Syrian opposition. It was very difficult for Hezbollah to justify its military involvement in Syria. Actually, after Hezbollah’s open involvement in the Syrian conflict, Nasrallah had to appear more frequently in interviews, televised speeches, and public talks (Pollak 2016, 12). He stressed the righteous grounds for his group’s involvement in Syria and mentioned several times that Hezbollah used force as a last resort and only after the battlefield was already full with so many radical groups that tried to overthrow the Syrian regime. For Hezbollah, using force against Israel has always been the first and the only option whereas against the Syrian opposition, the group claimed that it had done its best to find a peaceful solution before it decided to intervene in Syria to support a functioning government.

With its intensive involvement in Syria and with its acquisition of many conventional weapon systems such as tanks and armoured vehicles, Hezbollah now looks more like a regular army than a militant group (McDonald 2017). Furthermore, the Hezbollah model is replicated in several countries in the Middle East (Smyth 2015).[2] It is still not obvious if various Shi’a groups in Iraq, Syria or Yemen will evolve into future Hezbollahs, but it will certainly be a significant phenomenon to follow in the coming years. Hezbollah in Lebanon was born as an armed group almost four decades ago and then it became what it is in 2017. For the groups in other countries, time will tell if the Hezbollah model can be replicable.

References:

Alahed News Website, May 2006, “Nasrallah: Resistance is a point of strength for Lebanon”

Accessed 17 January 2018 http://english.alahednews.com.lb/essay detailsf.php?eid=701&fid=11

Alahed News Website, 18 September 2009. “Full Speech of Sayyed Nasrallah on Al-Quds Day: We will Never Recognize’ ’Israel´s’’ Right to Exist”. Accessed 07 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=9193&cid=450#.WXyoUxXyjIU

Alahed News Website, July 2011. “Hizbullah SG Full Speech on 27-07-2011”. Accessed 07 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=15047&cid= 452#.WX5dDhXyjIU

Alahed News Website, February 2012. “Sayyed Nasrallah Interview with Wikileaks Assange:”. Accessed 09 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/ essaydetails.php?eid=19645&cid= 453#.WX97cxWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 18 February 2013. “Sayyed Nasrallah: Resistance Will Not Stand Still on Any Aggression Against Lebanon”. Accessed 09 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=25016&cid=454#.WZf37PhJbIU

Alahed News Website, 25 May 2013. “Sayyed Nasrallah Delivers Speech on Resistance and Liberation Day”. Accessed 09 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=25839&cid=454#.WYHlbBWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 14 June 2013. “Sayyed Nasrallah,’s Speech “Day for the Wounded””. Accessed 09 January 2018. https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=25548 &cid=454#.WYD5whWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 25 May 2014. “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech on Resistance and Liberation Day- May 25, 2014”. Accessed 09 January 2018.

https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=26268&cid=556#.WYIiARWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 06 June 2014. “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech during Memorial Ceremony for Sheikh Kassir”. Accessed 09 January 2018.

https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=26357&cid=556#.WYIo-hWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 03 November 2014. “Sayyed Nasrallah [Full Speech] on 9th of Muharram: Our Battle is with Takfiris, ’Israel’”. Accessed 12 January 2018.

http://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=27799&cid=556#.WZILsdJJbIU

Alahed News Website, 25 May 2015. “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech on Resistance and Liberation Day”. Accessed 19 January 2018.

https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=29492&cid=562#.WYNUxBWLTIU

Alahed News Website, 06 March 2016. “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech on the Commemoration Ceremony of Martyr Leader Ali Fayyad”. Accessed 29 January 2018.

https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=32513&cid=570#.WYQ-BBWLS1s

Alahed News Website, 13 August 2016. “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech on the Divine Victory Anniversary”. Accessed 29 January 2018.

https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=34603&cid=570#.WYQ6BhWLS1s

Alagha Joseph, 2006. The Shifts in Hezbollah’s Ideology – Religious Ideology, Political Ideology, and Political Program. Amsterdam University Press

Al-Manar News Website. 16 February 2017. “Sayyed Nasrallah Promises Israelis with Game Changing Surprises!”. Accessed 20 January 2018. http://english.almanar.com.lb/193675

Cragin Kim, 2007. “Understanding Terrorist Ideology”. Accessed 11 January 2018. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/2007/RAND_CT283.pdf

Daher Aurélie, September 2007. “Lebanese Hezbollah, an Instrument of Iran’s Foreign Policy ?”, Accessed 31 January 2018. www.aureliedaher.com

Das Ramon, 2006. “Making Moral Sense of the Israel-Hezbollah War”. Human Rights Research, 1-34

DeVore, Marc R. 2012. “Exploring the Iran-Hezbollah Relationship: A Case Study of How State Sponsorship Affects Terrorist Group Decision-Making.” Perspectives on Terrorism Vol 6, No. 4-5, 85-107

Feirahi Davud, 2017. War and Military Ethics in Shi’a Islam (Lion of Najaf Publishers)

Hu Zoe, 2016. “The history of Hezbollah, from Israel to Syria”. Accessed 21 January 2018 http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/10/history-hezbollah-israel-syria-161031053924273.html

Heidekat Jay P. 2010. “Hezbollah’s Resistance”. Constructing the Past, Vol. 11, Issue 1, 96

International Crisis Group (ICG), May 2014. Lebanon’s Hizbollah Turns Eastward to Syria. Middle East Report N. 153

ICG Report. 2017. “Hezbollah’s Syria Conundrum”, Report Number 175

IslamAwareness, 2017. “Jihad in Islam: Preemptive or Defensive?”. Accessed 23 January 2018. http://www.islamawareness.net/Jihad/preemptive.html

Khadduri Majid, 1955. War and Peace in the Law of Islam. (The John Hopkins Press)

Kızılkaya Z. 2017. “Hezbollah’s Moral Justification of its Military Intervention in the Syrian Civil War”. The Middle East Journal, Volume 71, Number 2, Spring 2017, 211-228

Mortada Radwan, 2013. “Has Lebanon Entered the Era of Suicide Bombings?”. Accessed 03 January 2018. http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/17660

McDonald Jesse, 2017. “Special Report: How Iran is exporting the Hezbollah model to dominate the Middle East”. Accessed 11 January 2018. http://globalriskinsights.com/2017/11/iran-export-hezbollah-model-influence-middle-east/

Otlowski Tomasz, 2015. “The civil war in Yemen and the geopolitics of the Middle East region”. Accessed 11 January 2018. https://pulaski.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Pulaski_Policy_Papers_No_08_15_EN.pdf

Pollak Nadav, 2016, “The Transformation of Hezbollah by Its Involvement in Syria”, The Washington Institute For Near East Policy, Research Notes No.35, 1-21

Qassem Naim, 2005, Hizbullah: The Story from Within, trans. Dalia Khalil (London: Saqi)

Saad-Ghorayeb Amal, 2002. Hizbu’llah. Politics of Religion. (Sterling: Pluto Press)

Samaha Nour, 2015, “Day of mourning in Lebanon after deadly Beirut bombings”. Accessed 22 January 2018. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/11/isil-claims-suicide-bombings-southern-beirut-151112193802793.html

Smyth Philip, February 2015, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and its Regional Effects”, Policy Focus 138, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Ssenyonjo Manisuli, 2012, “Jihad Re-Examined: Islamic Law and International Law”. Santa Clara Journal of International Law. Vol 10. Iss.1

Sullivan Marisa, 2014, “Hezbollah in Syria”, Institute of Study of War Middle East Security Report, N.19, April 2014

S.Israel, 2018, “Lebanon strikes out after U.S. funds withheld”. Accessed 02 February 2018. http://supportisrael.us/news/lebanon-strikes-out-after-u-s-funds-withheld/

Takeyh Ray, 200, “Iran, Israel and the Politics of Terrorism”. Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 48:4, 83-96

YaLibnan 2018, “Hezbollah’s Death toll in Syrian civil war tops 1263”. Accessed 03 February 2018. http://yalibnan.com/2015/10/28/hezbollahs-death-toll-in-syrian-civil-war-tops-1263/

[1] In August and November 2013, Hezbollah’s strongholds in southern Beirut were attacked by suicide bombers (Mortada 2013). On 12 November 2015, ISIL killed 43 people in Beirut in two suicide attacks (Samaha 2015).

[2] In Iraq, the Shi’a Popular Mobilization Forces (Hashd Al-Sha’abi in Arabic) have played a critical role in the Iraqi government’s efforts to defeat ISIL in central and western parts of the country. “Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Iraqi Hezbollah, Saraya al-Khorasani and the Badr Organization” have been some of the groups that acted in Iraq while maintaining the ties with Iran (McDonald 2017). In Yemen, Iran is also accused of creating a Hezbollah model with its support to Shi’a Houthis in the country (Otlowski 2015).