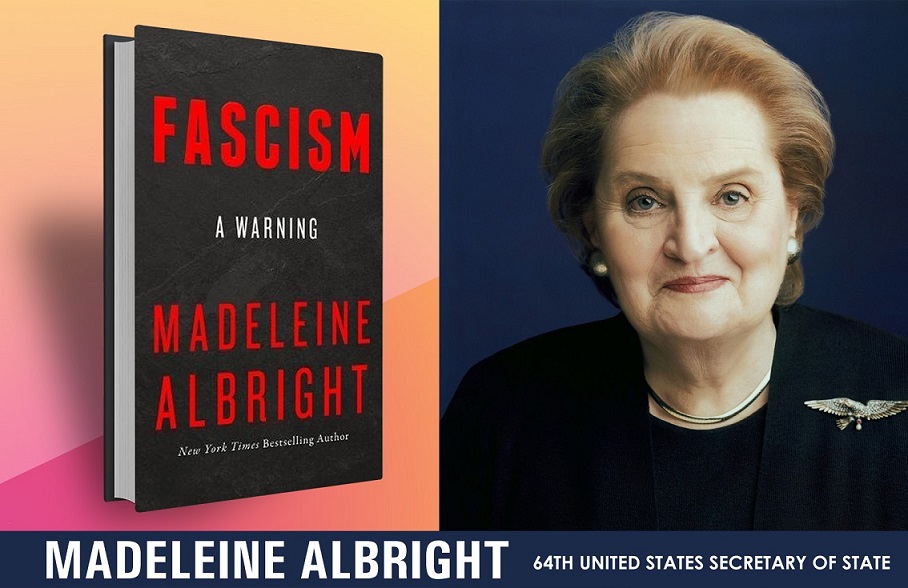

Watching Madeleine Albright introducing her latest book “Fascism – A Warning” in Georgetown University, her passion on the subject was unmistakable. As a victim of fascism, she spoke about her experiences as a small child in her native land Czechoslovakia, first facing Nazi invasion then communist coup. This is Madeline Albright’s sixth book since she finished her term as Secretary of State at Clinton administration in 2001. “I have found my voice late in my life, I have no intention to stop (talking) now” she said in a straight face. The book just does what she says, becomes her voice. As she was answering the questions of the moderator, the elephant in the room was no doubt Donald Trump. When the moderator asked the question “Do you think Donald Trump is a fascist?” her answer was a clear “No” without missing a beat. She explained that although she considers Trump anti-democratic, he falls short of the definition in critical areas such as use of force to advance agenda.

Albright believes that the recent wave of authoritarianism in the world is reminiscent of pre-WW2 Europe. She uses history to draw analysis and trends on how fascism take roots in a country. Well known figures of yesterday and today; Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Orban, Milosevic, Chavez, Kim Jong Il, Putin and Erdogan, all get their special chapters in the book.

The first part of the book offers historical content written in an easy-to-read style, full of accounts of events, anecdotes and quotes. However, history is not presented for the sake of history, as Albright paints a detailed picture of the philosophy behind fascism, preconditions that facilitated its rise and the methods used by the fascists. She asserts that works of philosophers such as Malthus, Galton, Darwin, Nietzsche and Freud which break away from traditional moorings and accept life as a “constant struggle to adapt with little room for sentiment, and no assurance of progress” has formed the backbone of fascist thinking. Anger and fear drawn from a public resentment and grievances, whether real perceptive or relative, are shown to be the main force behind the ideology.

The book draws common themes of the early 20th century fascism such as; promises of everything to a widely dissatisfied public, appearance of common men, constant blame of outsiders for all problems of the nation, use of a very effective propaganda machine and elimination of all opposition and dissent once power is attained. Although the public support behind Mussolini and Hitler is always depicted to be very high, author points to the fact that both men reached to power without ever having won a majority vote. Thus, in countering fascism, one can draw the conclusion that, precautions should be taken early before the demagogue in power; closes democratic pathways within the political machinery, uses state apparatus to silence the opposition and poisons the minds with ruthless ideology.

The book identifies that fascist movements were also existent in rest of the Europe and US. It appears that those movements never managed to reach a breakthrough size before world was shocked by the horrors of their predecessors in Italy and Germany, after which they died down quickly.

Albright offers exceptional insight into the psychology of fascism, presenting it as a part of humanity and not an exception. The belief that, others are getting treated better than they deserve and one is not getting what he is owed, opens the doors to fascism. She points out that, “Even people who enlisted in such movements out of ambition, greed, or hatred likely either were unaware of, or denied to themselves, their true motives”. In the absence of an effective mechanism to assuage anger, the economic and social discontent is exploited by a leader who offer prizes that seem worth giving up democratic freedoms. Albright shortly offers a philosophical cure to fascism but doesn’t explain how this is to be achieved. The idea that we are all created equals is the “single most effective antidote to the self-centered numbness that allows fascism to thrive” she declares in one chapter but quickly presents the challenge in another chapter: “Respect for the rights of others is a lofty principle; but envy is a primal urge”.

Albright -by no means- views the world through Pollyannaish lenses but she has managed to keep her belief for a more democratic world despite what she has lived and seen. “People often ask if I am an optimist or a pessimist, I am an optimist that worries a lot” stated Madeleine Albright in his speech which drew a chuckle from the audience. She asserts that “Good guys don’t always win, especially when they are less divided and less determined than their adversaries”.

The book offers interesting insight into issues such as historical collapse of fascism and a comparison between fascism and communism.

Albright draws attention to the startling rapidity the fascism collapsed in Italy and Germany. The man who were considered embodiment of the nation became target of firing squad or took their own life. In a single day, you could no longer find a single admitted fascist. The comparison of communism and fascism shows that the supposedly opposite ideologies have more commonality than one might think. “A dictatorship by any other name is still a dictatorship” declares Albright and goes on to explain that both speak the language of violence, detest popular governance and freedom of expression, all the while being riddled with ironies.

The chapters devoted to the dictators of modern times; Chavez, Erdogan, Putin and Kim Jong Il contain insightful historical analysis on why fascism was able to flourish in those countries, all the while enrichened by interaction of Albright with them, throughout her tenure.

Overarching theme of these chapters depict how all these leaders were accepted as a reformer that succeeded providing economic or social relief initially, succumbed to authoritarian tendencies over time and tie their bleak future with their country.

The book is rich in content, reflecting authors personal experience and expertise in the subject. It has a cross disciplinary approach, including elements of history, policy making, psychology and sociology. The book and its title might be viewed “Alarmist” by some concludes Albright. Her response is a single word: “Good”.