Introduction

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has moved the topic of defence to the epicentre of the political debate in the transatlantic zone. Responding to the new circumstances, the German government recently announced a massive scale-up of the country’s defence ambitions. These ambitions are part of a greater pattern within the context of “restrengthening NATO,” transitioning from “brain-dead” status, as famously dubbed by the French president Emmanuel Macron, to a highly responsive alliance that even saw enlargement in Europe, aiming to deter Russian aggression.

The central question is: “Where will Germany position itself in the future European defence architecture?” Germany, as the largest country in the European Union, has long been taking on the role of the engine of the bloc. Yet, while European countries are raising investments and political attention for their armed forces, the perspective role of Germany and its armed forces has not yet been determined.

In his famously received “Zeitenwende speech,” literally meaning “turn of an era,” German federal chancellor Olaf Scholz signalled a reorientation of the hitherto rather passive German foreign policy. Several moves so far also confirm the picture built at this speech. To start with, the country has announced raising its military budget. A special fund of 100 billion Euros is set to produce relief for financial misallocation of the past, as well as continuously missing the NATO 2 % goal. Recently, the chancellor even elaborated on his concept of “Zeitenwende” by illustrating an ambitious roadmap for a more outward-oriented European Union in a keynote address at the Charles University in Prague.

Yet, the issues are not as straightforward as deduced from Scholz’s speech. While Germany appears to rearm and build up its capabilities to back up a more active foreign policy by military means, its government has also shown hesitation to follow such an active foreign policy and present a tough stance towards Russia. Examples supporting such ambiguity include delaying the supply of heavy weapons to Ukraine or its indecision to introduce fierce sanctions at the beginning of the Russian invasion.

Meanwhile, countries like Poland rush forward and produce headlines in this regard. Furthermore, demands by French President Emmanuel Macron for stronger European autonomy have, in large part, remained unanswered by the Germans in the past. Yet, the tides have turned, and new circumstances threaten the security in Europe.

Therefore, apart from releasing warm promises of investments, the question remains whether Germany is ready, capable, and willing to align with states such as France or Poland on the matter and take up more military and foreign policy responsibility in Europe and NATO. A respective assessment of potential German military capabilities will help shed light on answering this question.

Analysis

1. Context: Lack of German Clarity in a European Security Landscape

Especially the countries that have been in close proximity to the warzone and have been deeply impacted by the Russian invasion have manifested renewed push to their military posture and political stance in European defence politics. These include, for example, Poland, which now borders a war zone alongside the three Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Even before the invasion, all four states were already among the eight out of thirty NATO states that hit the alliance’s spending target of 2.0 % of their GDP, with Poland reaching the level of 2.34 %.

Despite its already high defence spending and maintaining a solid defence corps, Poland currently plans to increase its defence budget to 3 % in the coming year, going hand in hand with massive investments in military equipment, such as agreeing to buy 250 M1A2 Abrams battle tanks from the United States. The country also plans to double the size of its currently 143.500-strong armed forces. Furthermore, since the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Poland has been calling upon NATO and the United States to increase their presence within its borders. An undertaking which has now materialised with establishing a permanent US Headquarters in the country.

Meanwhile, the Baltic states have also reinforced their commitment to NATO by further boosting their defence spending in response to the Russian aggression. Furthermore, reacting to the demands of the Baltic states, NATO has agreed to double the number of its combat-ready battle groups on its Eastern flank in the framework of its forward presence operation, bringing the number of multinational battlegroups to eight. This stance was also reaffirmed by its commitment to increase the size of these battlegroups from battalion to brigade size, marking great support for the Baltic states’ defence capabilities.

Such developments, as seen in these four examples, fit well into the rhetoric leveraged by especially the last two US Presidents that Europe should take more responsibility in providing its own security. Although for not the same reason, French president Emmanuel Macron also advocates Europe should scale up its defence capabilities to attain “strategic autonomy.” France has long advocated taking on more leadership tasks in the European Union in this regard. Macron had already made clear in 2018 that his country would invest in a robust military and meet the NATO 2 % target. Furthermore, after Brexit, Macron called upon the burden of increasingly shaping European security to be split between his country, as well as Poland and Germany. In the current situation, such ambitions are especially required in foreign policy matters. While Poland rushes forward, including its notable support for Ukraine, France seems to have found its position.

Since Angela Merkel retired, a figurehead that can unite European ambitions into a long-term vision, has not yet emerged. Seeing the current developments in Europe and the threat posed to the continent by the Russian aggression, the question arises where Germany stands in this security landscape and if the country is ready to invest more in Bundeswehr or its armed forces to project power.

2. Political and Public Attitudes Towards the Role of Bundeswehr

Although Germany naturally seems responsible for taking on a leading role in the European Union by having the bloc’s biggest economy and population, the matter is far from being easy. Especially Germany’s complex past often restrains political decision-makers from diverting away from a diplomacy-oriented and pacifistic foreign policy.

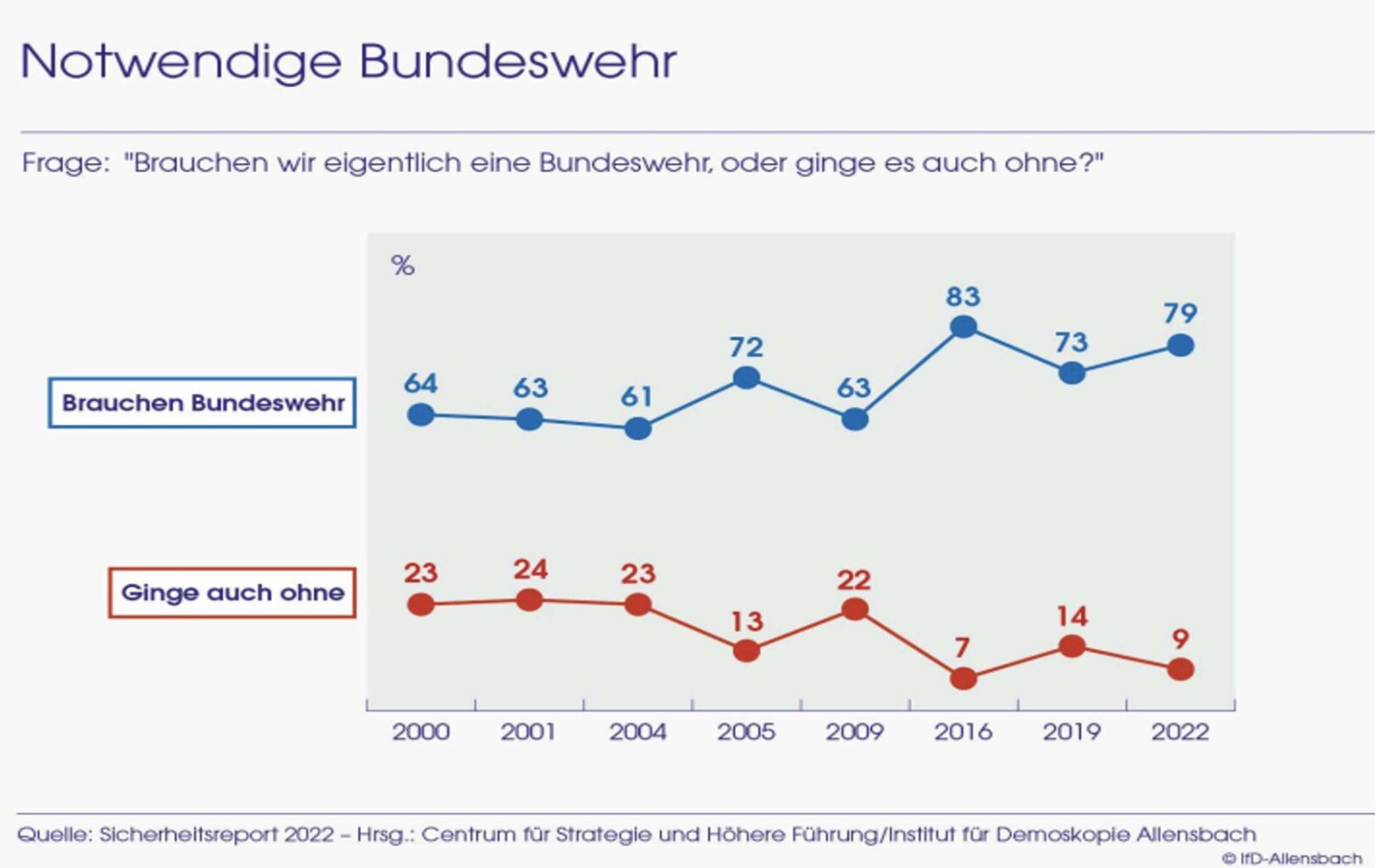

Such curbing beliefs do also resonate in society. According to a long-term study commissioned by the German ministry of defence investigating public opinion on the Bundeswehr (the German Armed Forces) between 2010 and 2020, a great majority of German nationals prefer soft foreign policy measures over use of hard power. This more precisely means prioritising diplomatic channels and economic aid over use of military forces in crises and combat. Likewise, the opinions on increase in the Bundeswehr budget have been indecisive. Although the public generally has a positive attitude towards the armed forces and the latter seems well integrated into German society, breaking such strongly held beliefs of decades-long self-effacement is difficult.

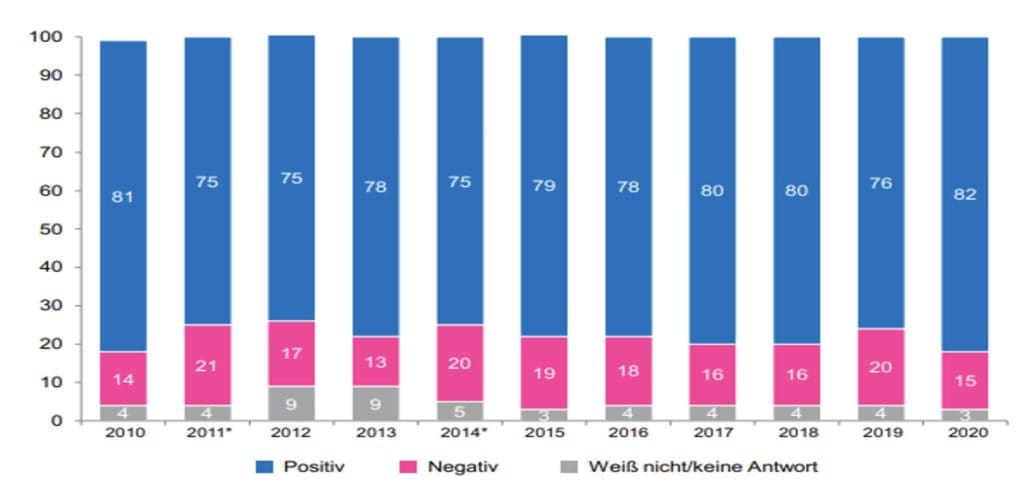

Figure 1: The figure shows the development of German public opinion on the necessity of maintaining the Bundeswehr. Although Germans clearly agree on the necessity of maintaining armed forces when posed this question…. (Source: Sicherheitsreport 2022, Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach)

Although the parties in government have officially affirmed their ambitions towards a more active foreign policy that also foresees the use of hard measures when push comes to shove, a consensus seems far from sight. The leading party in government is the Social Democratic Party (SPD), which is the party of both the chancellor and the minister of defence, Christine Lambrecht. With the Zeitenwende speech, as well as statements issued by Lambrecht calling for the Bundeswehr to be a “fully capable army” and a “European strength multiplier,” officials of this governing party seem to be positive about a more active role for the German armed forces.

|

Figure 2: …and answer positively when asked about their personal attitude towards the Bundeswehr, … (Source: “Forschungsbericht Trendradar 2021,“ Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr) |

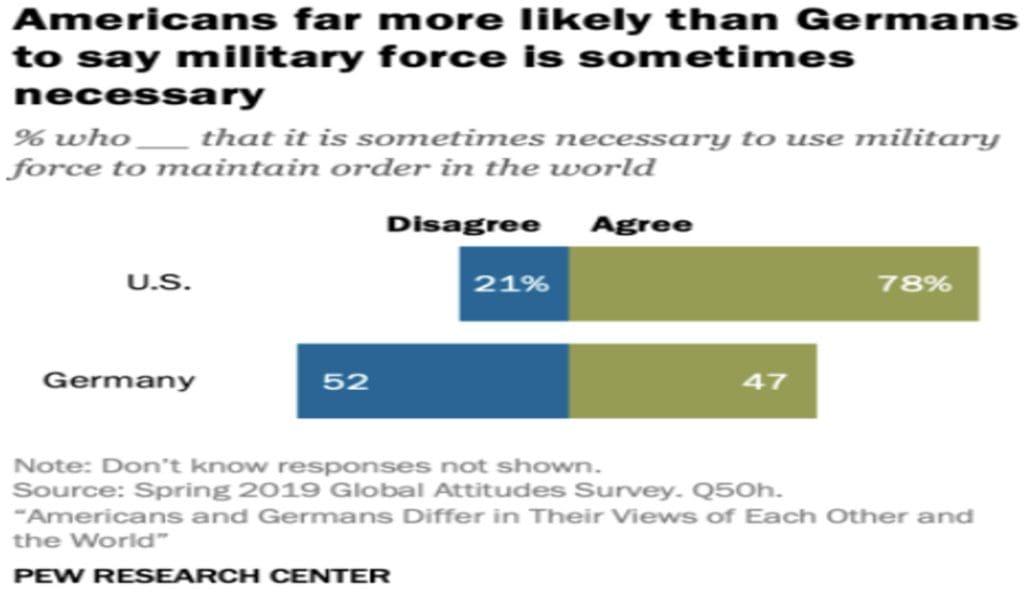

Figure 3: …still, the commitment to and acceptance of military force and combat operations in society is lower in Germany than in the NATO partner USA (Source: “Americans and Germans Differ in Their Views of Each Other and the World,” Pew Research Center). |

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the SPD was also part of the previous coalition government under Angela Merkel, where the party stood out as a critic of investments into a stronger Bundeswehr. An example was when it blocked the acquisition of armed drones in 2020. Needless to say, the circumstances have changed. Yet past and recent ambitions of the party paint an incongruous picture that probably sets the scene for intense internal discussions.

The second biggest party in government are the Greens. In its election program, the Greens envisioned support for a stronger and well-equipped German army, greater integration of European armed forces and more coordination with NATO partners. Furthermore, particularly the Green foreign minister Annalena Baerbock has so far been pushing for a more decisive stance against Russia when she, for instance, criticised chancellor Scholz for delaying heavy weapon supply to Ukraine. However, while the Greens seem ready to take on more military and foreign policy responsibility, the party originates from peace movements in the 1970s and 1980s. This legacy could turn into a crucial test for the Greens in the long run. The youth organisation of the party has, for example, already vowed antipathy to the special fund for the Bundeswehr.

The third biggest party in the government is the Free Democratic Party (FDP), the main liberal party. The party’s chairman and minister of finance, Christian Lindner, has spoken out in favour of the massive investments into the Bundeswehr. In parliament, he committed his government to the goal of creating one of the most capable and powerful armies in Europe to live up to the relevance and responsibility that Germany has. Although Lindner’s statements are strong, it needs to be awaited whether actions will follow. As a strong supporter of frugal spending, he and his party have made clear that they stand for the constitutional debt-brake and will not accept further debts to finance the Bundeswehr’s rearmament, a principle that could slow down the process.

Thus, although a general commitment towards a stronger German role on the international stage can be identified, a consensus is far from being reached both within the governing parties as well as between them. Especially the Bundeswehr, though accepted as a necessary cornerstone for such commitment, has probably not gained the full political and public support needed to also develop into such. Therefore, the political situation within Germany showcases severe hindrances to more active German involvement in the military sphere. Overcoming these is a necessary pre-requisite for Germany to meet its envisioned responsibility in this regard.

3. How Promising is the Bundeswehr Strengthening Project?

By now, it is clear that Germany will invest 100 billion Euros more into all departments of its armed forces in addition to the budget already planned. This announcement aligns with a comprehensive Bundeswehr modernising program announced by Ursula von der Leyen, the then defence minister, in 2015. The special budget has received attention worldwide, triggering questions on what Germany’s place in the European security architecture and on the international stage would be. Although the investments are massive on paper, boosting Germany’s defence spending to a record high, it is disputable whether they will also translate into the contemplated military power.

Out of the 100 billion Euros, one-third alone shall be used to modernise the Luftwaffe, the German air force. By replacing, among other things, its old jets with American dual-capable F35 fighting jets and the new generation Eurofighter ECR, the Bundeswehr, for example, invests in new capabilities, including the potential carrying of B-61s or Tactical Nuclear Weapons, thus contributing to NATO’s nuclear deterrence. Especially the decision to buy F35 jets presents an interesting case that could signal to Washington that Germany is interested in strengthening the transatlantic bond and thus also increasing its responsibility in NATO. Such an announcement is good news, also for NATO, in which the USA, especially under Trump, has long been calling for increased burden-sharing.

Furthermore, by committing 16.6 billion Euros, the land forces will, for instance, be equipped with new tanks. At the same time, the navy is set to receive a new frigate and a corvette due to a departmental budget increment of 8.8 billion Euros. Lastly, about 21 billion Euros will be supplied for digitalisation and C2 capabilities.

Moreover, the investments are also meant to speed up research and development projects in all departments. The special budget will, for example, be committed to further develop the Future Combat Air System, a joint air defence project by France, Spain, and Germany. Meanwhile, the money will be used for the land forces to develop a new generation of tanks, the main ground combat system. The navy will be further supported in the development of the new submarine type 212 CD. Lastly, 422 million Euros are allocated for R&D to ingrain the use of artificial intelligence technology in the Bundeswehr. The money taken from the special budget will be added to the established and approved budget for research, development, and procurement which amounted to 10.3 billion Euros in 2021. In this regard, the special budget could indeed boost important R&D in this field, considering Germany’s expenditure in this branch only amounted to 18.6 % of its total defence spending. As such, Germany represented one of the five NATO countries with the lowest share of money spent in this regard.

However, at least three reasons can be brought forward that support doubts about the workability of this investment undertaking. First, the Bundeswehr has long been fighting massive underfunding and inoperability problems. The ministry of defence has become close to being a magnet for general criticism. Most recently, the general inspector of the standing army has given room to his frustration by calling the Bundeswehr out for being “more or less bare” and missing options to deter Russia. Keeping such criticism in mind, the special budget for the Bundeswehr should not spark enthusiasm in everyone hoping for more German commitment. Rather, it offers Germany a chance to rehabilitate the financial mistakes which were made in the past. In this light, the minister has admitted that the money will also be used to simply reach the level of equipment of its NATO partners, something that appears to be necessary after the policy of cuts followed in the past.

Second, the government authority that is responsible for armament projects and investments taken by the Bundeswehr (Bundesamt für Ausrüstung, Informationstechnik und Nutzung der Bundeswehr – BAAINBw) is a bureaucratic giant that is massively criticised for being slow, notoriously inefficient, and usually finishing projects at a higher price than the initial bidding. Although the German parliament has already worked on overcoming such problems to speed up procurement processes, criticism remains, even from government members. Considering how Germany, although below the 2 % goal of NATO, has one of the best-funded militaries in the world in total numbers, a big chunk of the problem that the army needs to tackle rather seems to be this very inefficiency, illustrated by the BAAINBw.

Third, besides understanding the need for the special budget for the Bundeswehr, critics have noted the lack of planning certainty that goes along with such an “investment firework.” While deficiencies can now be corrected in the short term, the government has yet failed to introduce a suitable long-term strategy that respects issues like the necessity of upscaling the military industry, respective production capacities or the administration. Furthermore, the government plans to stick to the debt-brake as soon as possible again. However, as military developments usually require up to 15 years of lead time, future governments are directed into problems of military financing knowingly, which only delays some of the current issues.

Thus, on the one hand, the Bundeswehr seems set for the modernisation of its equipment and increasing responsibility in NATO. On the other hand, political uncertainty and criticism still surround the armed forces. Due to several improvements needed, the recent government project of raising the defence budget has, therefore, not yet proven to be completely convincing in strengthening Germany’s position on the global stage in the long term. Rather, the project seems to be born out of a general reactionist political mood calling for convincing answers to the shocking new geopolitical reality. Although announcing investments is at first convincing, the defence budget itself is not everything. A comprehensive approach requires a broader overhaul of the armed forces and its related industries for the ambitions not to turn out to be a flop.

Concluding Assessment: Is Germany Ready?

While European countries reaffirm their commitment to stronger militaries, countries like France and Poland stand out in their military ambitions. Yet, the role of Germany so far seems less clear.

In response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, Germany’s new tricolour government has appeared to be willing to overcome problems made in the past and to make Germany a more active player on the global stage. Especially the Bundeswehr has moved to the epicentre of attention. Accepting the military as a valuable asset in a more active foreign policy, the government of chancellor Scholz has promised unforeseen investments to improve the equipment of the armed forces.

However, the Bundeswehr deals with more problems than just its equipment. A lack of a real political consensus regarding its future role, efficiency issues in its public procurement, or the ambiguous public opinion symbolise symptoms of an army in need of a broader overhaul. Therefore, questions such as “is the special budget really that much?” or “is the German rearmament project really that ambitious?” should be revisited from this perspective.

Immense investments cannot simply correct the Bundeswehr’s severe problems. Rather, the political authorities should focus on overcoming the hurdles which led to these problems, ranging from a diverse stack of political to organisational ones. Issues, just as the ones pointed out, caused Germany not to be efficient in translating its economic power into military might. Before pouring money with a watering pot (a German political saying describing the waste of money), internal organisational processes should be overhauled to make the special budget an efficient endeavour.

Any conclusion based on Scholz’s Zeitenwende speech that Germany now plans a greater role for the Bundeswehr for projecting greater power should therefore be reconsidered. Before Germany can live up to the foreign policy and military responsibility that many expect of the country, immense work must be done for the army to portray the capabilities needed.

[*] Mats Radeck is a research assistant intern at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. He also follows a master’s program in International Relations with a special focus on “Global Conflict in the Modern Era” at Leiden University.