Abstract: A presidential summit of the Caspian littoral countries is expected to be held soon this year. The convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea is highly likely to be signed by all the five littorals at the summit. However, there are significant issues still on dispute relating the Caspian Sea. One of them is the construction of trans-Caspian pipelines carrying hydrocarbons from east to west, specifically the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) project, which is intended to transport natural gas from Turkmenistan to Europe. This paper has investigated the stances of relevant parties regarding TCP project, analysed the explanations of several key persons on the coming summit and on TCP distinctively, and tried especially to estimate Russia and Iran’s plan for the TCP and how they would work to achieve their targets on the coming summit. Finally, the paper aims to present the results indicating that Russia, together with Iran, plans to restrict Turkmenistan build a gas pipeline on the Caspian with the disguise of environmental concerns.

Introduction

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan emerged as independent and so the new littorals of the Caspian Sea. Then existed legal regime of the Caspian Sea between Russia and Iran turned out to be inadequate to meet contemporary requirements and to regulate the mutual relations of the Caspian States mainly in terms ofdelimitation and exploitation of natural resources (UN, 1998).

So, it is required to be updated. However, to date, for twenty-seven years, littoral countries could not manage to sign an exhaustive regulation. In the beginning, the discussion had a ‘legal status’ orientation. But, the Caspian has both sea and lake specifications, so no distinct legal status was fully appropriate for it. Eventually, under the influence of their conflicting interests, littorals could not agree on which legal status and its respective law setting to implement for the Caspian. Disagreements led the way to negotiations and then to power politics instead of peaceful dispute resolution mechanisms of international law. Moreover, since the early 2000s, on a few different occasions, the problem even caused Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan come close to armed-conflict and Russia use gunboat diplomacy[1] which followed by a rigorous arms race in the region until now. Therefore, further disagreements have a potential to ignite a conflict in the Caspian region. Like the Middle East, any possible destabilisation in the region would have strong global effects. So, it’s vital for the world peace that the littorals agree on a lawful, reasonable, and a robust legal regime for the Caspian Sea.

Suddenly, on December 2017 after Caspian Foreign Ministerial meeting in Moscow, when there was no mutual ‘public’ expectation for solution to the chronic legal regime problem, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov surprisingly said: “I am pleased to tell you that we have found solutions to all outstanding key issues linked with this document. The text of the convention is practically ready.” (Pannier, Qishloq Ovozi…, 2017). He was talking about the convention on the legal regime of the Caspian Sea. One of the main issues regarding with the legal regime was whether a multilateral consent is obliged for an underwater gas or oil pipeline across the Caspian, although only the agreement between parties through whose territories the pipeline passes is required according to international law (UNCLOS, 1982). Dispute on seabed borders between Azerbaijan-Turkmenistan-Iran is also among the leading problem topics. This issue is reservedfor later articles. On this article, we will take the first issue and comment on the implications of the coming convention for the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP).

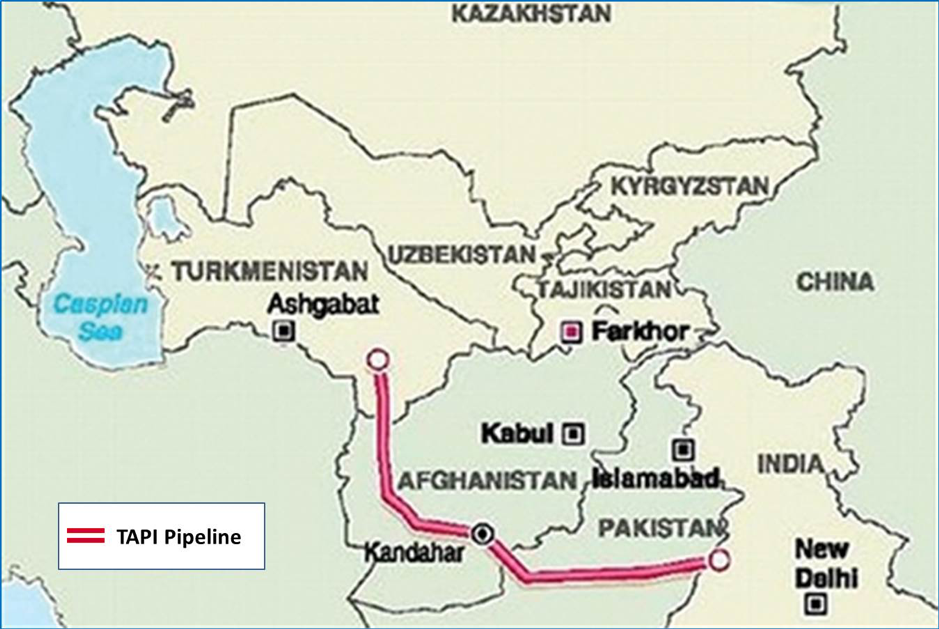

Figure 1: Possible Route of Trans-Caspian Pipeline (Behorizon, 2018)

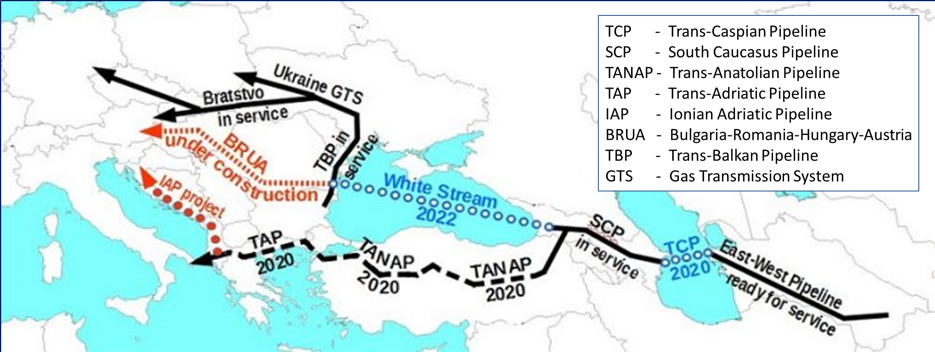

Regarding the TCP project, since it was first suggestedin 1996, Turkmenistan had been trying to realise it. The project aims to transfer Turkmen gas to Azerbaijan across the Caspian Sea (Figure 1). The next step is to send the gas to Europe through Georgia and Turkey. Currently, Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) pipelines, shown in Figure 2, from Azerbaijan to Europe are expected to be ready by 2020. The internal pipelines from Turkmenistan’s eastern fields are also ready to feed the subsea pipeline. Moreover, nowadays, Turkmenistan is having the worst economic crisis ever in their history. So, they are in dire need of gas revenues; and TCP has the potential to boost Turkmen economy.

Figure 2: Southern Gas Corridor Pipelines (Meydan TV, 2016)

On the other hand, Russia and Iran have strictly opposed the pipeline that will bypass them. Although their real concerns were economic and political, they were continually citing lack of overall agreement on the legal status of the Caspian and environmental impact of the pipelines. In reality, if TCP were constructed, Turkmen gas would be a strong rival in their Western markets. Thiswould cause adverse effects not only for their economies which are highly dependent on hydrocarbon sales but also for Russia’s political power over the EU which politically exploits EU’s dependence on Russian gas. So, from economic and political points of view, the possibility of Russia and Iran to sign a convention that will give freedom to Turkmenistan construct the TCP seems to be very low. Furthermore, most of the explanations of related officials and comments of experts strongly imply that Russia and Iran will not allow any pipeline across the Caspian.

The convention is expected to be signed by the heads of Caspian States in the Astana Summit soon this year. So, the present paper aims to guess as precisely as possible the outcome of the summit regarding Trans-Caspian Pipeline. Within this goal, it’s hoped that the public, the academics and the governments of related parties, especially of Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, EU, and the US not to get caught underprepared to overcome the implications and do their best in advance to get their rights according to international law from the upcoming convention. The first section of the paper provides the rationales behind the support of TCP by the prospective exporter (Turkmenistan), the importer (EU), the transit countries (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey), the US and Western energy companies. Section II explains the neutrality of China regarding the project. Section III focuses on why the TCP project is opposedby Russia, Iran, Gulf countries and Russian energy companies. Section IV analyses the explanations of several key persons, experts and reporters on the coming summit and TCP specifically. Section V tries to estimate Russia and Iran’s plans for the TCP on the forthcoming convention. And finally, Section VI concludes that Russia, together with Iran, plans to impose other Caspian littorals (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan) a convention that gives Russia and Iran the option to block any infrastructure contrary to their interests, under the guise of environmental concerns.

This article is the first piece of a four-article series dealing with essential issues on the dispute for the expected Caspian convention. Next article will try to provide with suggestions for relevant parties on how to implement Trans-Caspian Pipeline in spite of Russo-Iranian opposition. Last two articles will deal with the delimitation of the Caspian Sea in an equitable, proportional, and fair way according to the international law.

- Why is Trans Caspian Pipeline Favoured?

a. Turkmenistan: I Have Gas, I Cannot Sell It

Although it has plenty of natural gas reserves, Turkmenistan cannot produce much since it cannot sell more, mostly due to the lack of sufficient export infrastructures. It has the fourth-largest gas reserves after Iran, Russia, and Qatar in the world. According to (BP, 2017)statistics, it has 9.4% of the world total provengas; yet its production is just 1.9% of the world’s total. If it has more export options, it has a potential to produce and sell gas at least 5times the current amount; this means its fossil-fuel dependent economy can grow almost 5times. Therefore, it’s really important for Turkmenistan to construct pipelines to sell its gas. Maybe today it’s more important than ever before when the grave economic situation in the country is taken into consideration (Toktonaliev, 2017).

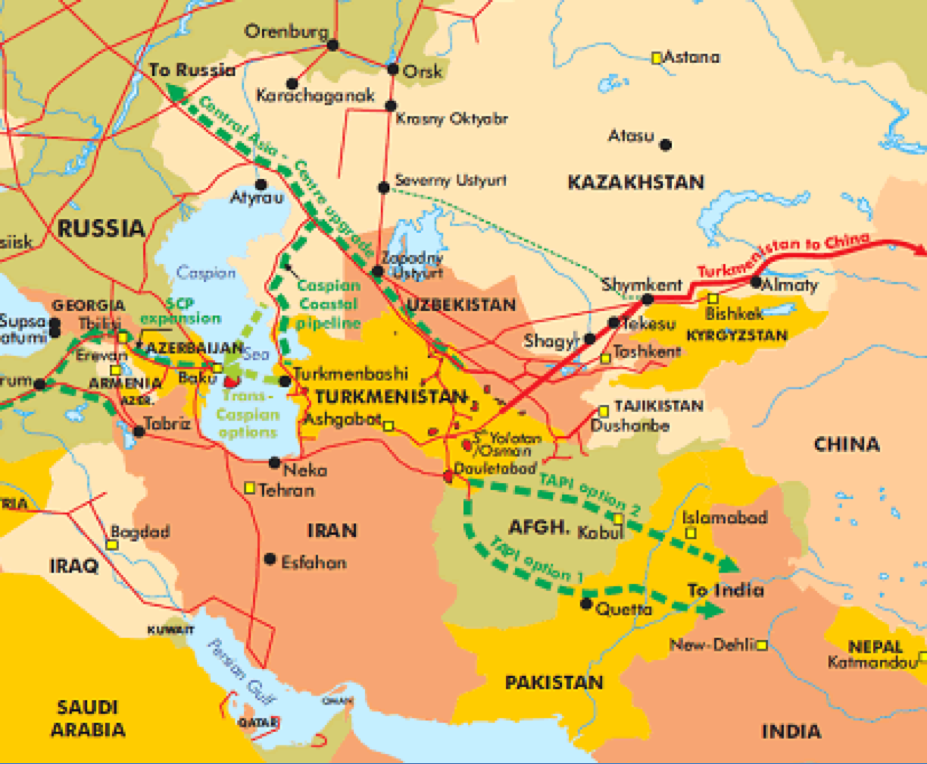

In order toefficiently transfer its gas to reliable markets, TCP project is one of the best options Turkmenistan has already been trying to implement (Sadikhova, 2017). President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov signalled even in 2007 that Turkmenistan seeks to develop a trans-Caspian gas pipeline, but to date, the project has not been implemented, yet. (Katzman, 2018). Moreover, since 2017, upon a disagreement on pricing with Russia and Iran, Turkmenistan started exporting almost all of its gas to China. So, China can be definedas Turkmenistan’s sole customer. However, this causes a monopsony[2] in the market, meaning the buyer to be tempted to lower the price knowing that the seller has no choice other than accepting it (Eurasianet, 2016).

Furthermore, Turkmenistan repays numerous Chinese loans from most of the profits for gas exports to China (The Chronicle of Turkmenistan, 2016). According to Igor Yushkov, a senior analyst of the Russian National Energy Security Fund (FNEB), another problem for Turkmenistan in China is that Russian state company Gazprom envisages expansion to the Chinese market and its pipeline projects can compete with additional pipelines from Turkmenistan to China (EADaily, 2017). Considering all above and the vulnerability of depending so heavily on exports to China, as once was the case for exports to Russia, Turkmenistan needs new consumers (Cutler, China’s geo-economic…, 2017).

Regarding Turkmenistan’s customer diversification efforts, a gas pipeline project to satisfy mainly India’s demand, TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) (Figure 3) is still ongoing, though with doubts. It’s under construction since 2008. It has financing and security problems (Eurasianet, 2018). In addition, the total annual gas demand of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India is less than 30 billion cubic metres (bcm)(BP, 2017), and it’s not likely for them to buy all of their demands from Turkmenistan which would be contrary to the supply diversification principle. So, according to (BP, 2017)data, it seems that Turkmenistan’s exports on TAPI would be, very optimistically, 20 bcmannually, at most.

Figure 3: Route of TAPI Pipeline (Georgia Today, 2017)

However, on the Far West, there is a giant and reliable energy consumer demanding gas from Turkmenistan: the EU. The annual energy demand of the EU is about thirteen times higher than that of TAPI’s customers; it’s approximately 400 bcm. And for Turkmen gas to reach the EU, the most efficient export directions are through TCP and South Caucasus Pipeline via White Stream and/orTANAP (Trans Anatolia Pipeline), as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Pipelines Proposed to Carry Turkmen Gas to Europe (Energy Ministry of Georgia, 2018)

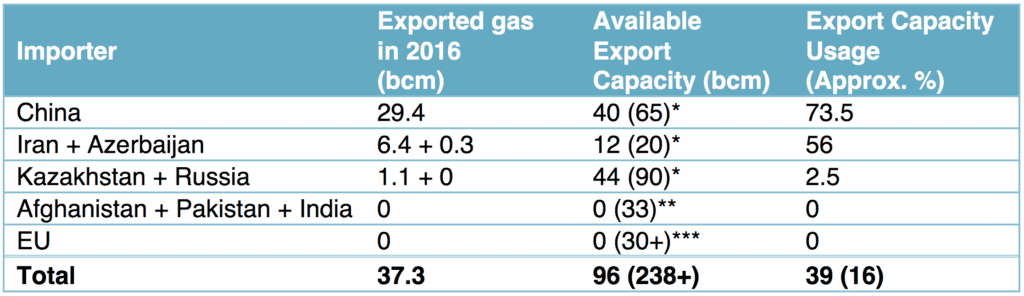

TCP has a potential to boost Turkmen economy. The table below shows Turkmenistan’s gas export amounts, currently available and potentially available export capacities, and capacity usage ratios according to export data in 2016. As seen in Table 1, through the existing pipelines (not including TCP and TAPI), Turkmenistan currently has the capacity toexport gas up to 96 bcm, but exports 37.3 bcm, so uses only 39% of its capacity. Even if we assume that there is no increase in exports to China, when TCP is realised, Turkmenistan will almost double its exports. So, considering its poor economic conditions, constructing Trans-Caspian Pipeline is the best option for Turkmenistan to recover.

Table 1: Turkmenistan’s Gas Export Capacity and Exported Amounts in 2016 (Behorizon, 2018. Sources: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2017; Energy Charter Conference, 2017; SOCAR)

* Numbers in parenthesis shows potentially available capacities when modernisation/expansionis made.

** TAPI pipeline, having financing and security problems is still under construction since 2008. There are serious concerns about the fate of it, but officially it’s expected to be in operation by 2022.

*** Through East-West Pipeline in Turkmenistan and via Trans-Caspian Pipeline, if project realises.

Another alternative might have been using the Soviet-era pipelines, as seen in Figure 5, to connect Turkmen gas to Russian gas network, and then to transfer it to Europe. However, current Russian outlets toEurope are full. EU has an amendment proposal to its Gas Directive, Russian Nord Stream-2 and Turk Stream projects do not comply with it, so Russia is expected to have problems even to sell its owngas to Europe, let alone Turkmen gas (European Commission, 2017). Additionally, regarding the Russian option, the reliability of the customer considering its trade history (Hays, 2016)and its respect for the rule of law (Buckley, 2018)are also factors that need to be taken into account. Therefore, regarding gas exports, the only viable solution for Turkmen economy to recover is TCP.

Figure 5: Present and Prospective Gas Pipelines from Turkmenistan (EADaily, 2017)

b. EU: I Need Your Gas, I Cannot Buy It

EU wants to include TCP to Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) for supply diversification purposes and thus enhance its energy security (Council of the European Union, 2017). Currently, it relies mostly on Russian gas and Russia used its gas exports to EU as a weapon in bilateral political conflicts. Therefore, EU is in search of alternative gas supplies for years, especially after the Ukraine crisis in 2014.

One of the significant alternative supply projects of EU is SGC. It connects Shah Deniz-2 deposit of Azerbaijan in the Caspian to Europe. The project is expected to be finished by 2020. Initially, Azerbaijan is expected to put 10 billion cubic meters annually (bcma) gas in the pipeline for Europe (Zeynalova, 2018). And if Turkmen gas will also join the project by the construction of TCP, it will pump at least 30 bcmaextra gas (Azernews, 2017).

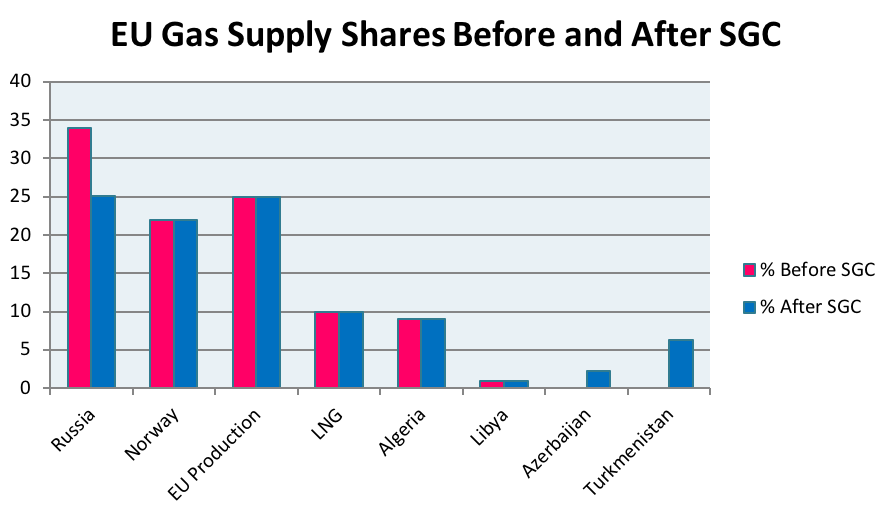

SGC has a great potential for breaking Russia’s monopoly. EU is conducting several other projects concerning supply diversification (e.g. East-Med, Romania off-shore, new LNG terminals etc.) and energy efficiency which is promising good results. However, on the negative side, trends show that EU’s own gas production will decrease in the future. So if we assume that the ins and outs neutralise themselves causing no change at all in the supply scheme, Azeri and Turkmen gas to be put in SGC, by itself only, can make dramatic changes to break Russian monopoly. Graph 1 shows the supply scheme before and after SGC in order to see how important SGC’s marginal effect is. As seen in the graph, Russian share on EU gas supply decreases roughly from 34% to 25% when Azeri and Turkmen gas is pumped to Europe via SGC. Note that, calculation here is based on the assumption that the EU will buy Azeri and Turkmen gas wholly as an alternative to Russian gas.

Graph 1: EU Gas Supply Shares Before and After SGC (Behorizon, 2018. Source: ENTSOG-GIE, 2017)

c. Transit Countries: More Gas, More Fees, Enhanced Defence

Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey would be transit countries provided that Turkmen gas is put on SGC. It’s apparent that they are going to earn more transit fees when more gas is pumped through the pipeline. Also, their defences would also be enhanced, since to secure its strategic gas supplies EU would include these countries inits defence (energy security) plans which will benefit those countries with extra protection.

d. The US: I Want to Diminish Russo-Iranian Energy Dominance

The US has always fully supported the TCP since it was first suggested. American energy companies are indeed the originators of the TCP project. The US wants to ensure hydrocarbons flow unimpeded from the Caspian region so that Russian and Iranian ability to use these resources as foreign policy tools to coerce neighbouring nations and destabilise the region will be decreased. Also, by TCP, she wants to diminish Russia’s regional monopoly of hydrocarbons while creating a wedge between Russo-Iranian energy cooperation to mitigate global natural gas domination (O’Neil, Hawkins, & Zilhaver, 2011).

e. Western Energy Companies: We Want What Maximizes Profit

For Western energy giants’ points of view, TCP is the most profitable alternative to transfer Central Asian hydrocarbons to global markets with high demand. Those companies have generally wanted such disputes to be solvedwith the economically optimal solution for them. It’s not about the costs only. Reliability, safety & security, and transfer speed are also among the factors in effect. Thus, for them, the economically optimal transfer method of gas from the east side of the sea to the west is ‘via a subsea pipeline’. With a subsea pipeline, the transportation costs would be lower since the path would be shorter and the number of transit countries who claim payment would be less. Moreover, fortunately, the sea is not too wide and not too deep which lowers the costs further. Instead of pipelines around the sea, a pipeline across the sea is not only cheaper but also more reliable, safe & secure, and faster. It is more reliable, more secure and safer because by decreasing the number of the transit countries, the possibility the gas flow to be impededdue to factors such as political crises, military conflicts, terrorist attacks, and pricing disputes would be decreased. It’s also faster since simply it’s shorter.

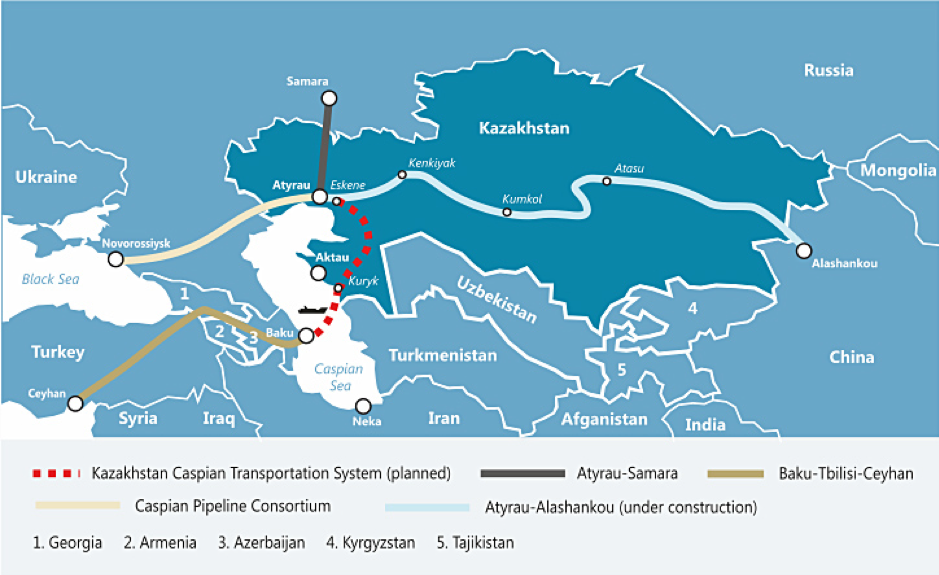

A similar solution is also optimal for Kazakhstan’s offshore Kashagan oilfield. As shown in Figure 6 with red dashes, the operating company plans to expand the production and transport the excess oil across the Caspian to Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline via tankers. However, if the Russo-Iranian hindrance on pipelines is surpassed, pipeline probably would replace tankers since it is the economically optimal transfer method.

Figure 6: Transfer Structures for Kazakhstan’s Caspian Oil (North Caspian Operating Company, 2018)

f. Pro-TCP Camp

Due to the various benefits of the project to them, Turkmenistan, EU, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, US and Western energy companies favour the TCP. For expanding the Southern Gas Corridor, EU currently negotiate with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan on a Trans-Caspian pipeline to transport gas across the Caspian Sea (European Commission, 2018). Southern Gas Corridor Advisory Council which comprised of all the entities above except Turkmenistan and energy companies also states that SGC is open to future participants (SGC Advisory Council, 2015).Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan signed an MoU on energy cooperation in August 2017, EU put the TCP on its List of Projects of Common Interest in November 2017, the most recent U.S. National Security Strategy stated that Washington will “help our allies and partners become more resilient against those that use energy to coerce” and“support the diversification of energy sources, supplies, and routes at home and abroad” (Cutler, Commentary…, 2018).

However, as Senior Advisor to the Turkmen President Yashgeldi Kakaev said there are still no tangible actions other than intent statements (Karayianni, The “expanded” Southern…, 2018). The main problem of the pro-TCP camp is that Russia threatens to use force to prevent the construction of TCP, and there is not enough bargaining power of the West at the Caspian Sea. Two countries on the opposite sides of the sea cannot lay pipelines between them. The pipeline even would not cross from any other country’s section. But since it’s against the interests of Russia, it blocks the TCP by threat of force.

- The Neutral – China: “Let them fight!”

Economically, China would not want to lose its favourable monopsony position and would oppose Turkmenistan sell its gas to alternative customers via TCP. Since 2017, after a disagreement on pricing with Russia and Iran, Turkmenistan started to make almost all of its imports to China. So, China can be seenas Turkmenistan’s only customer. Thiscauses a monopsony in the market, meaning the buyer to be tempted to lower the price knowing that the seller has no choice other than accepting it (Eurasianet, 2016). Therefore, if the seller (Turkmenistan) has another choice (the EU), then monopsony breaks. That is the principalreason why China would not want TCP.

Politically, China does not want Central Asian states to save themselves from authoritarian leaders by whom it exerts influence to those countries. It financially supports authoritarianism in Central Asia by means ofBelt and Road Initiative (Munich Security Conference, 2018). If the TCP is realised, the need for Chinese financing will reduce, so the influence of China; moreover, a customer having influencing power, the EU, will strongly emerge in the political arena of Central Asia. In this context, China might prefer the Turkmen gas go to India rather than to the EU.

On the other hand, at the Conference of ‘Oil and Gas of Turkmenistan’ in November 2017 in Ashgabat, the Director General of CNPC International Turkmenistan Li Shulian told that China is ready to give financial support to TAPI and TCP if it’s realised (EADaily, 2017). In addition, for Chinese, EU serves as a useful ‘legitimiser’ of Chinese global political and economic activities, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Benner, Gaspers, Ohlberg, Poggetti, & Shi-Kupfer, 2018). So, there is reasoning for China to support EU’s projects financially as it’s the case for a China-led investment consortium, Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) support for SGC (Shafiyev, 2018). And furthermore, it should be noted that TCP is in harmony with China invested Trans-Caspian International Trade Route.

Consequently, if we combine those issues together, we might assess that ‘perhaps’ China could also support TCP, though not overtly, to take declining Russia’s place in Central Asia. However, since it’s a strategic ally of Russia, it seems more reasonable that China, for now, would downplay in Central Asia, let the Russia fall by itself or by the West and keep its neutrality for the TCP.

- Why is Trans Caspian Pipeline Opposed?

a. Russia and Iran: It’s Our Weapon, We Will Not Drop It

Since TCP was first suggestedin 1996, Russia, along with Iran, constantly opposed not only TCP but any pipeline project on Caspian which will have adverse effects on Russian strategic control on the energy flow from Central Asia to Europe (Karayianni, Is the Trans-Caspian…, 2018). They’ve argued that until the legal status of Caspian Sea is defined (by consensus), no cross-pipeline can be constructedwithout the consent of all the five littoral countries.

One of their two main concerns about TCP was economic. Turkmenistan was already a rival for them in the Chinese market. With access to the West directly via TCP, Turkmenistan, and maybe later Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, would be strong opponents of Russian hydrocarbon supply dominance and demand dependence over Europe and those of Iran’s over Turkey. Actually,there is co-dependence between EU-Russia and Turkey-Iran, even the latter’s dependency on their customers are bigger than the former’s reliance on the suppliers. More specifically, according to 2016 data, EU imports 34% of its gas from Russia, but Russia exports 80% of its gas to EU. Similarly, Turkey imports 21% of its gas from Iran, but Iran exports 92% of its gas to Turkey (ENTSOG-GIE, 2017)(Gazprom, 2018)(BP, 2017). If the TCP is realised, then, gas demand from them would decrease and so Russia and Iran’s revenues. Extra gas from Turkmenistan might also have a negative effect on gas prices also which would reduce their revenues further. The decline in their gas revenues will have a tremendous impact on their economies which are heavily basedon fossil-fuel exports. On the other hand, while Central Asian gas flows through Russia, it receives sizable transit fees and attains price mark-up by reselling the fuels through Russian controlled pipelines (Geopolitica, 2013).

Moreover, currently, Russia’s position in EU gas market is not stable. EU Commission’s amendment proposal on EU Gas Directive disallows Russia to export gas to the EU via Nord Stream-2 and Turk Stream pipelines. EU didn’t allow South Stream, too. So, Russia laid Turk Stream instead of South Stream to circumvent Ukraine to punish it by making lose it $2B transit revenues per year. However, the disagreement between EU and Russia resulted in Gazprom’s 50% capacity cut on Turk Stream. On the other side, the EU is divided into two about Nord Stream-2’s future. Added to Turk Stream, ongoing uncertainty over

Nord Stream-2 might force Russia to find new gas markets, and EU to find new supplies. Consequently, in this complexity, to preserve its position on the EU market, Russia is highly likely to block Central Asian gas to reach Europe as much as it could, (Maritime Working Group, 2018).

Their other concern is political. Russia’s transit monopoly position for Central Asian fossil fuels gives Russia leverage to control the Central Asia politically, and by letting the TCP, Russia would not want this position to be broken. On the other hand, while Central Asian gas flows through Russia, it has more oil and gas with which to secure greater leverage in international politics (Geopolitica, 2013). Same arguments are also valid for Iran although to a lesser degree.

b. Gulf Countries: We Don’t Want Rivals Either

According to (Janusz-Pawletta, 2015), the strategic importance of the Caspian deposits lies not in their actual size, but in their role in diversifying sources of energy for countries seeking resources outside the Arab region. Although only gas is at stake on the TCP, if it could somehow be realised, another pipeline for carrying Kazakh oil to Azerbaijan can also be thought of in the future. Therefore, oil and gas exporting Gulf countries, simplywould not want to share their reliable European customers, would support TAPI instead of TCP, and keep opposing any other pipeline across the Caspian. I believe the general manager of a UAE company, the Dragon Oil Turkmenistan Ltd. (the biggest foreign investor in Turkmenistan), best describes the will of Gulf Countries about where they want Turkmen gas to go, instead of Europe: “… (Turkmenistan) hasfavourablegeographic proximity of countries such as China, India, and Indonesia, which account for more than 50% of the world’s young and growing population. Growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) of these countries increased by an average of 34%… To continue to maintain high rates of economic growth, countries of this region need clean energy, that is, natural gas. And who, if not Turkmenistan, can best help meet the needs of these countries for energy?” (Rabi, 2015)

c. Russian Energy Companies: Long Live The Monopoly

Russian oil and gas monopolists believe that it’d be better to “allow” the delivery of the energy to China and India rather than to “break” the delivery monopoly of Russia towards Europe (Geopolitica, 2013).

d. Opposition Camp

Since they do not have any valid environmental or legal grounds, to support their opposition, Russia and Iran mainly rely on their military power in the region. However, as a rare occasion, recently on 5 May 2018, Iranian Science Minister Mansour Gholami stated in a meeting with Putin’s special representative for cooperation with Caspian Sea countries that they would cooperate with Russia to halt deterioration of the environment in the Caspian Sea (IFP, 2018).

- Analysis of Comments and Explanations

a. Comments and Explanations Arguing that Russia and Iran Will ‘Not Allow’ TCP

The analysis of the explanations of several key persons, the comments of hydrocarbon industry experts and reporters on the coming summit and specifically on TCP highlights that the convention proposed for the next Caspian Sea summit will not allow TCP project to be implemented(without the consent of all the five littorals).

For example, Igor Bratchikov, Ambassador-at-large of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the head of the Russian delegation to the multilateral talks on the Caspian Sea, speaks openly as much as a diplomat can and implies that Russia is against TCP citing environmental concerns. On an interview with Caspian Energy (CE) Magazine in 2016 which was republishedon Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ official website, he answered a question about how the positions of the parties on the construction of Trans Caspian pipelines changed. He said that Russia’s position had not changed and was quite open. He argued that Russia was firstly concerned about the environment rather than the economyof the project. And he defined Russia’s stance on the final decision for the construction of TCP thatall the five Caspian states had the right of the votesince the environmental issues affected them all. “Unilateral action on construction of Trans Caspian pipelines is inadmissible,” he threateningly concluded. (Bratchikov, 2016)

In his interview, Bratchikov almost explicitly states that Russia is against TCP and it is using environmental concerns to simulate as if its opposition is legal. He also implies, by calling the unilateral action for TCP as ‘inadmissible’, that it’s Russia’s red-line and Russia might even consider using military force to prevent TCP from being realised (Shlapentokh, 2014).

On 12 December 2017, one week after Lavrov’s explanations about the Caspian convention, Bratchikov again answered questions of Caspian Energy (CE) Magazine. This interview gives us information about Russia’s latest view of TCP from the first mouth and proves that it has not been changed. Bratchikov answered a similar question as in 2016 about whether Russia’s stance on Trans Caspian pipelines had changed. He gave similar answers but this time mentioned small details which give us hints about the method Russia would use to achieve its target in terms ofthe TCP. He again said that Russia’s stance had not changed, but this time he emphasizedthe construction of ‘main’ pipelines. He again talked about the environmental concerns, but this time mentioned the Tehran Convention which was related tomarine environment. And differently from 2016, this time he didn’t underline the right of vote for all the states ‘openly’, instead he used these words which would not draw any ‘public’ reaction in Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan: “We are pleased to note that the parties were able to find verified formulations on this principal issue in the draft Convention” (Bratchikov, 2017).

The ‘verified formulations’ mentioned in his last sentence above probably mean ‘the draft protocol on environmental impact assessment in trans-boundary context to the Tehran Convention’. As it will be explainedin detail in section V, that protocol serves as the concrete form of environmental disguise covering up Russo-Iranian efforts to block the ‘main’ (large diameter) pipelines on the Caspian, i.e. TCP.

Nonetheless, critics may argue that Russia is genuinely pursuing environmental well-being of the Caspian Sea and that there is no clear evidence that its efforts are against TCP. In this point, we could get some insights from the Director of National Energy Institute of Russia, Sergei Pravosudov.Probably, with the confidence of not-being a diplomat and thinking that the government needs his advice, Pravosudov speaks more openly than Bratchikov, and eventually reveals the real reasoning behind ‘the environmental concerns’.

On 7 November 2017, he answered questions of Mice Times Asia (MTA) regarding ‘Turkish Stream Pipeline’. One question of MTA was about problems that may arise with Turkey. He responded that the problem with Turkey is that she is not against Trans-Caspian Pipeline, wanted all the pipes to visit her, and supported the competition of Russia’s pipelines. Then, to block the TCP, he advised to competently negotiate the delimitation of the Caspian Sea or even to postpone it for an indefinite period. He urged that otherwise,the Europeans would buy Central Asian gas via TCP at the expense of Russian gas which would decrease Russia’s profits. Lastly, he suggested that Russia should only agree on the delimitation of the sea with the condition that: “…the pipeline to Europe can be built only with the consent of all littoral states” (Pravosudov, 2017).

Resulting from the above statements of two prominent figures, we understand that Russia’s stance on TCP has not changed, and it still opposes it. Another argument for the continuing objection of Russia to TCP and Russia’s alternative as compensationfor Turkmenistan could be the strategic partnership agreement signed by the presidents of Russia and Turkmenistan on 2 October 2017. Before the agreement, Turkmen President was trying to find ways to save the TCP deal. Lately, he had visited Azerbaijan in August 2017 and signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on energy cooperation which was perceivedas a step forward to the TCP. However, on 2 October 2017, Turkmenistan woke up the day with a decent example of Russian political warfare. A stunningnews appeared in Russian media on the very date when Putin would meet with his Turkmen counterpart in Ashgabat. Russia was relocating its Caspian Flotilla from the Northern Caspian city of Astrakhan to the West Caspian. The subheading of the news of Izvestiya read: “Swimming pool with missiles”[3] will allow Russia to monitor the situation in the Middle East and Central Asia.Although there was no significant military threat to Russia from CentralAsia, the reason for Central Asia being statedin the subheading should be relevant with Russo-Turkmen summit. Fortunately, on the following lines of the same news, a political scientist, the head of the Institute of Caspian Cooperation, Sergei Mikheev, gave Russia’s message clearly as crystal. He explained that Caspian region was increasingly interested in by third countries. He added: “It is rich in oil and gas. In addition, an alternative energy corridor from Central Asia to the West through the post-Soviet Transcaucasus can pass through it[4]. This idea is promoted by Americans and Europeans, but the Russian Federation and Iran are against it.”Sergei Mikheev also explained that the Caspian is a valuable asset for the Russian military since it is located close to the Middle East region and is directly adjacent to Central Asia (Mikheev, 2017). The message given by Russia to Turkmenistan via this news and Mikheev’s comments was open: “If you continue to try to realise Trans-Caspian Pipeline project, you should also consider facing with the Russian military.”

This was not the first time Putin used Caspian Flotilla as a tool for ‘gunboat diplomacy’. In April 2002, at the Caspian Summit in Ashgabat, he declared that Caspian Flotilla would conduct a big exercise soon. After his explanations, in May of that year Kazakhstan, and after the exercise in August, Azerbaijan in September adopted bilateral agreements signed with Russia.

More recently, on 7 October 2015,four warships of the Russian Caspian Flotilla launched a total of 26 Kalibr cruise missiles at ISIS targets in Syria, which is locatedabout 1500 kilometres away. Those missiles were thrownat ISIS, but more importantly, their side effects were probably targeted at Turkmenistan. Russia had already military facilities in Syria and military ships in the Mediterranean to strike ISIS targets there more conveniently, but Moscow had chosen to use its assets in the Caspian. This choice suggests that the strike was a show of force not only to West but also to CentralAsia, especially to Turkmenistan who was trying to strengthen its military, realise TCP project and not bow down to Russian requests for the sea. With regards to Russian requests, it should be statedthat Russia wants to oblige other littorals to get its approval before launching a project in the Caspian Sea, specifically pipeline projects. For this purpose, Russia and Iran suggested provisions in the draft protocol on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in a Trans-Boundary Context to the Tehran Convention (Framework Convention for the Protection of the Maritime Environment of the Caspian Sea) obliging the parties who intend to lay large diameter (main) subsea pipelines in the Caspian Sea to take the approval of other Caspian littoral countries for the EIA.However, Turkmenistan had refused those provisionsand offered instead to include all pipelines, such as the smaller pipelines connecting offshore deposits to the shore, to be constructedwith the approval of all littorals, not only the large diameter ones, probably toretaliate if other littorals deliberately block its projects. And this continuing stance of Turkmenistan also might have triggered the Russian show of force in the Caspian.

As a result, after the October 2017 visit of Putin to Turkmenistan, there were signs that things have changed in spite of Turkmenistan’s reluctance. Being badly in need of money, Turkmenistan desperately seems to be surrendered to Russia’s pressure on abandoning the TCP project and signing the EIA protocol that leaves the fate of TCP forever to the consent of other littorals. As compensation, Russia might have offered Turkmenistan energy cooperation and support for the TAPI project.

Firstly, as for energy cooperation, comments of Myrat Archayev who the acting head of Turkmengaz is, match with the compensation argument above. On 1-2 November 2017, at the International Conference of “Oil and Gas of Turkmenistan-2017” in Ashgabat, Archayevdeclared, ‘out of nowhere’ (Pannier, Unpacking Lavrov…, 2017), that Turkmenistan is ready to supply gas to CIS countries and Eastern Europe via Russia by the Central Asia-Centre gas pipeline. “…If mutually acceptable agreements are reachedwith buyers and transit countries, this gas pipeline could potentially be used…” he stated further (EADaily, 2017).

However,in reality, especially in the gas sector, it’s almost impossible for Russia to provide Turkmenistan even a so-so alternative for the TCP, let alone a matching one.A senior analyst of the National Energy Security Fund (FNEB),Igor Yushkov, argues that the Russian option is hardly possible to carry Turkmen gas to Europe. He claims that Gazprom will not agree to be a transit vehicle for a competitor. According to him, Gazprom has not fully loaded its own capacities and was glad to cancel the contract for the purchase of Turkmen gas as early as last year (EADaily, 2017). Indeed, it can be inferred from Senior Advisor to the Turkmen President Yashgeldi Kakaev’s statements in the Fourth Ministerial Meeting of SGC Advisory Council on 27 February 2018 that Turkmenistan also knows that there is no better replacement for the TCP.Kakaev had told there: “It (the TCP project) should be addressed with some sense of urgency. It is time to start working on the project, instead of simply discussing it”(Karayianni, The “expanded” Southern…, 2018).

Secondly, as another compensation for TCP, on the strategic partnership agreement, Russia might have offered support to Turkmenistan for its other project, TAPI. Note that, TAPI was a never-ending-since-1995 project backed by the US and known to be opposed by Taliban. And Taliban is allegedly supported by Russia and Iran (Nicholson, 2018) (Votel, 2018). However, after the strategic agreement in October 2017, unexpected developments occurred in TAPI project raising suspicion that their cause might be the Russo-Iranian effect. A ceremony for the TAPI held in the Afghan city of Herat on 23 February 2018. Interestingly, it was reported on 22 February 2018 that Herat officials told that insurgents who were trained by Iran to disrupt the ceremony had switched sides and joined the government. A spokesman for the Taliban and a Taliban splinter group led by Rasul Akhund that operates in the north-west ofAfghanistan have both pledged to protect the construction of TAPI through Afghan territorysince it is a ‘national project’. (Pannier, Afghan TAPI Construction…, 2018).

By the way, Russia is also supporting Iran’s IPI (Iran-Pakistan-India) project which is rival to TAPI. And while TAPI seems to be hopeless, IPI is more likely to be realised. IPI does not pass through war-torn Afghanistan. Iran is Russia’s strategic ally while Turkmenistan ‘declares to be’ neutral. Iran has ties with Russia regarding Eurasian Economic Union and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Their foreign policies are generally in line with each other. Russia conducts operations in cooperation with Iran in the Middle East. So, it seems that Russia’s support to TAPI, if there is really, is ostensible and lasts only until the Caspian Sea Convention which exactly fits Russia’s interests is signed.

In this context, we are afraid that Turkmenistan was forced to cooperate with Russia in return for promises impossible to be kept, even though Turkmenistan acknowledges the impossibility of those promises.

After elaborating much on the region’s major power Russia, let us now look at the current stance of the other opposer, Iran. AlikeRussia, Iran also has not wanted a trans-Caspian pipeline bypassing Iran. His stance has not been changed, either. Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Asia, the Pacific and the Commonwealth and Iran’s representative for the Caspian Convention Special Working Group, Ibrahim Rakhimpour’s statements on the interview with Iranian Students’ News Agency on 9 December 2017, right after Lavrov’s speech, reflects Iran’s recent view on the issue from the first mouth: “We do not oppose this issue (TCP), but we have an environmental sensitivity in this field, and we are trying to make sure that there is no violation of environmental standards in this area”(Rakhimpour, 2017).From this statement, it’s understoodthat Iran will continue acting together with Russia to impose provisions in the EIA protocol obliging the parties who intend to lay large diameter submarine pipelines in the Caspian Sea to take the approval of other Caspian littoral countries for the EIA. In the end, those provisions will serve as ‘legal’ excuses to block the TCP project.

b. Comments and Explanations Arguing that Russia and Iran Will ‘Allow’ TCP

Statements above argue that in the coming convention Russia and Iran want to restrict TCP citing environmental concerns. However, some experts are against this view. For instance, former U.S. Ambassador to Kazakhstan and to Georgia, who is now an adjunct senior fellow at the RAND Corporation, William H. Courtneyclaims that Russia might allow TCP to break Chinese influence in Central Asia (Courtney, 2017). However, should Russia allow TCP, then EU and US would increase their influence in Central Asia; and it’s a fact that Russia sees the Western influence more dangerous for its interests than Chinese influence.

Second, an advisor of SOCAR, an academic, Brenda Shaffertells that among several energy regions in the world only Caspian got new investments last year in spite of low fuel prices (Shaffer, 2018). Thismight be perceived as a signal for the TCP since energy companies would want to maximise the return of their investments by the most profitable transport options available and it’s for sure that TCP is one of them. Another one might be a submarine oil pipeline from Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan. For instance, North Caspian Oil Company, the operator of the Kashagan offshore oil field of Kazakhstan and whose majority shareholders are Western energy companies, has production expansion plans. If they are realised, the territory of Azerbaijan will emerge as an additional export corridor for Kashagan’s excess oil via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. As it is statedon the Company’s website, oil is planned to be transferred to Kuryk port of Kazakhstan by an on-shore pipeline and then via tankers [or via a future pipeline across the sea which is cheaper] to Baku (Maritime Working Group, 2018). Nevertheless, the projects and investments favouring TCP certainly show that the energy companies want which is the most profitable for them, the TCP. Yet,it is what Western energy companies wish to. It’s of significance only to the degree of those companies’ power to pressure on Russia and Iran at the expense of the latter two’s profits. It seems that they don’t have that much power for now. For instance, BP could not stand up even against Iran in 2001 on the dispute of Alov-Araz-Sharg oil field between Azerbaijan and Iran. Besides, the recentannouncement of the capacityexpansion of Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which is a Russian majority joint company, might be considered as a counteraction to NCOC’s oil transport plans through the Caspian Sea. The reason is that CPC’s plans are in perfect consistency with Russia’s stance to TCP or any westward transport method from Central Asia bypassing itself (Maritime Working Group, 2018). Even though the other players find better alternatives, Russia would try its best to have all the westbound energy flow from Central Asia through itself, just as Bratchikov said:“Let those, who intend to invest in such projects, think about the economyof such projects, their efficiency and financial payback. But the environmental side of the issue primarily concerns the Caspian littoral countries – each of the Caspian littoral states without exception.” (Bratchikov, 2016)

Third, the Head of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Azerbaijan office, Nariman Mannapbekov, told that ADB wouldsupport SGC, but she mentions only Azeri gas at the initial stage, adding that other sources can also connect to the project later (Shafiyev, 2018). Thismight also be claimedas a support for the TCP. Thus far,ADB is a China-led investment consortium, andwe have mentioned China’s neutrality earlier in Section III. China offers support to TCP only if it’s realised. However, since there is a degree of convergence of interests and norms between Russia and China in Central Asia rather than a competition, fornow, it’s highly likely that China would be neutral with regards to TCP (Lemon, 2018).

Last but not least, Dr.Robert M. Cutler, a Senior Researcher at the Centre for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies of Carleton University, also thinks that Russia will allow TCP to save the authoritarian regime in Turkmenistan (Tahir, 2017). He justifies his views in several instances. As far as the ones I’ve encountered are: EU’s and Georgia’s growing interest on the TCP, Lavrov’s Dec. 5 explanations, Azeri Deputy Foreign Minister Khalafov’s statements (Cutler, How Central…, 2018); the acting Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs at the US Department of State, Sue Saarnio’s statements(EADaily, 2018); Azeri Energy Minister Shahbazov’s views, Senior Advisor to the Turkmen President Yashgeldi Kakaev’s attendance to the Fourth Ministerial Meeting of SGC Advisory Council on 27 Feb 2018 and his statements there: “it (the TCP project) should be addressed with some sense of urgency.It is time to start working on the project, instead of simply discussing it” (Karayianni, The “expanded” Southern…, 2018). Turkmen and Azerbaijani MoU on energy cooperation of August 2017, EU’s putting the TCP on its List of Projects of Common Interest in November 2017, the most recent U.S. National Security Strategy stating that Washington will “help our allies and partners become more resilient against those that use energy to coerce” and“support the diversification of energy sources, supplies, and routes at home and abroad” (Cutler, Commentary…, 2018).

Nevertheless, almost all of the instances above just show that Turkmenistan, EU, US, Georgia, and Azerbaijan want the TCP project to be implemented. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the project will be implemented. It just means that it is wanted to be implemented. However today, thanks to ‘Trump’s America First policy’, the US, leading power of the actors above does not have ‘enough will’ to force Russia and Iran to accept TCP. It has the power, but it lacks the will. The EU, as the secondary, economic, diplomatic power, has some troubles inside as Brexit, irregular migration, and the rise of anti-EU political parties. The EU tries to strengthen its cohesion. The other countries are weak and do not seem to be as steadfast as they should be on the issue. Therefore, Russo-Iranian side appears to have taken the initiative. Hopefully, the lawful and the beneficial happen, but the reality does not say so. So far,the situation is not desperate, which will be coveredin the next article.

Turning now to Lavrov’s Dec. 5 explanations, of which Cutler claims to be a signal to allow TCP, we can simplyargue that Lavrov did not say that they will allow TCP. He said that they’dfound solutions to all the key issues. As Bratchikov and Rakhimpourimply, those solutions are the solutions that fit Russia and Iran the most and as mentioned before they don’t include TCP.

With regards to the argument of saving the authoritarian regime, it would not be wrong to think that Russia would find simpler alternatives to support Berdymukhamedov (Hasanov, 2018)rather than risking his greater interests as was noted in Section II.

However, if Cutler wereright, it would be extreme naivetéto think that Russia would allow the TCP for just goodwill. Though it doesn’t seem to be likely that Russia would allow it, but if it were the case, Russia’s ‘tricky’ plan might be allowing TCP which would take some time to construct, carrying Turkmen gas through Russia in the meantime, slowing down the construction process as much as possible by negotiating environmental impact assessments and such. And at the end, through Southern Gas Corridor, Turkmen gas will already be passing through ‘Turkey’ which is becoming more and more pro-Russian and pro-Eurasian day by day that gives Russia strategic control of the pipeline. Moreoever it will be passing through Tbilisi which Russian controlled territory is just 30 miles away, and there is not any noteworthy physical obstacle to stop Russia from getting the strategic control of the pipeline, in case.But, again, since there are simpler and more direct alternatives, it seems that Russia would not take risks.

c. Limitations of the Analyses

The analyses in this section may have a limitation by accepting what the key people say reflects what they really think and what their countries really will do. So, it wouldn’t be wise to use only their explanations as an argument. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence to claim that the comments and explanations, arguing that Russia and Iran will not allow TCP, match perfectly with both the current economic and political interests and the historical stances of Russia and Iran which are providedin Section II and Section V.

- How will Russia and Iran try to Block TCP?

As noted before, Russia and Iran are opposed to the TCP. Although, in reality, there are economic and political reasons behind their objections, they have apparentlybased their opposition on lack of overall agreement on the legal status of the Caspian Sea and environmental issues (Socor, 2011) (Michel, 2015). Their stance has never changed. On 7 March 2000, they declared a joint statement to United Nations stating that “Russia and Iranopenly announce that theydo not agree to the implementation of any projects for Trans Caspian underwater pipelines, which pose an environmental threatin conditions of extremely active geodynamics (UN, 1999).”

Then they tried to achieve the veto right in a covert manner that can be readthrough their proposal on ‘previous versions’ of the draft convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea (from now onlegal status convention). “The Contracting States may lay main subsea pipelines on the floor of the Caspian Sea, under the condition that ecological expertise of these projects will be approved by all the coastal countries. The state laying the pipeline shall bear material responsibility for damages caused to the other Parties and to the marine environment occurring due to breakup of the pipeline” [Art. 13 (2) Abs. 3] [proposed by Russia and Iran] (Janusz-Pawletta, 2015).

They continued to the same stance on the most recent ‘draft Protocol dated 17 November 2017 on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Trans-Boundary Context’ to the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Maritime Environment of the Caspian Sea (hereinafterEIA protocol). First, in commercial means, the articles 9 and 15 of this protocol cause the TCP project to be unforeseeable to invest since the time frame of the EIA process is almost open-ended. Then, it gives Affected Parties (parties affected environmentally by the activity) limitless power to stall the project as long as they want.

Article 4 (2) of the EIA protocol proposes that if any country has a project of laying large diameter gas pipelines in the Caspian Sea, this project is subject to an EIA in a trans-boundary context which is a regular process in international law. The text of Article 4 (2) is as below:

“Each Contracting Party shall ensure that the proposed activities listed in Annex I to this Protocol (which includes large diameter pipelines for the transport of oil, gas and oil products, or chemicals), that are likely to cause a significant transboundary impact are subject to an environmental impact assessment procedure pursuant to this Protocolprior to a decision to authorize or undertake a proposed activity.” (Tehran Convention Secretariat, 2017).

However, Article 9 of the EIA protocol defines a too long 180-day consultation period, moreover with an option to even lengthen the period. It’s estimatedthat construction of the TCP would take about 2years to complete. It seems unreasonable for a 2-year-long project having EIA consultations ‘at least’ 6 months. However, according to article 5 of the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context of 1991 (the Espoo Convention), the time frame for the consultations should be reasonable.[5] The text of Article 9 of the EIA protocol is as below:

“Article 9. Consultation between Concerned Parties

Prior tomaking the final decision on the proposed activity, at the request of the Affected Party, the Party of Origin shall enter into consultations with the Affected Party, concerning, inter alia, measures to reduce potential transboundary impact.

(1) The Concerned Parties shall agree, at the commencement of such consultations, on a reasonable time-frame for the duration of the consultation period, while the period of consultations should not exceed 180 days unless otherwise decided during the consultation period.” (Tehran Convention Secretariat, 2017).

Moreover, if Affected Parties cannot agree on the EIA, the dispute is tried to be solved according to Article 15 of the EIA protocol. The dispute resolution mechanism brought by this article is inadequate especially for the Caspian Sea with a history of 27-year lack of overall agreement. It lacks a certain process and a strict timeline for resolution (Good Practices and Portfolio Learning Project, 2011). For 27 years, Caspian littorals made nothing more than consultations and negotiations. Isn’t it unreasonable to think that next time if they had a dispute they are going to solve it by consultations and negotiations? It seems that this provision justserves the legalisation of ‘superiority of power’ over the rule of law. The text of article 15 is as below:

“Article 15. Settlement of Disputes

Any dispute between the Contracting Parties concerning the application or interpretation of the provisions of this Protocol shall be settled in accordance with Article 30 of the Convention” (that is … the Contracting Parties will settle the disputes by consultations, negotiations or by any other peaceful means of their own choice)” (Tehran Convention Secretariat, 2017).

So, there is ample evidence that article 9 and 15 of the EIA protocol covertly give Russia and Iran the power to impede or even disallow any project they don’t want politically and economically under the guise of environmental concerns. The draft protocol degrades ‘EIA in transboundary context’ which is a technical process having universal standards, into a political process and makes it a subject of consultation and negotiation. It effectively discourages investors from any commercial project due to the lack of a certain timeline and a functional dispute resolution mechanism in the EIA process.[6] Moreover, it prevents the country of origin from implementing its project without having its EIA approved by all the affected parties.[7] However, on the international law, namely according to article 6 of the Espoo Convention[8], there is no requirement that the preferences of the affected country(ies) dictate the final decision of the country of origin. But “due account” must be taken of the consultations between the parties undertaken pursuant tothe Convention (Environmental Law Institute, 2009).

Critics again may claim that Russia and Iran’s environmental concerns should not be interpretedpessimistically. However, firstly, their own environmentally careless manner for the Caspian Sea is at odds with this argument. For instance, Iran pursues a project that transfers water from the Caspian Sea to its southern provinces to satisfy their need for water. But, according to Mohammad Darvish, a scholar at the Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands and an ex-official of Ministry of Environment of Iran, the pollution level of the sea is 40 times above the standard range, and if the water is transferred, Caspian Sea will be more salinized, threatening its ecosystem more than ever (Darvish, 2018).Apart from everything else, as mentioned by Mamuka Tsereteli, who is a Senior Fellow at Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, Russia’s ownmassive pipeline development in the Baltic and Black Seas spoils such an environmental argument (Tsereteli, 2017). With provisions related to the environment, Russia and Iran want to have the right to disapprove even a pipeline project to be laid only on Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan’s sectors. It will not pass from other littorals sectors. It was just as unreasonable as if Ukraine, Georgia and Romania had the right to disapprove Russia’s Turk Stream pipeline in the Black Sea which does not run into their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ); or as if Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia had the right to disapprove Russia’s Nord Stream 2 (NS2) pipeline in the Baltics.As for the NS2, a subject of international law, the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context of 1991 (the Espoo Convention) would be usedin EIA processes. Do you think Russia would agree that the EIA protocol proposed for the Caspian Sea is usedfor the EIA process for NS2 which obliges the approval of the EIA by Poland, for instance?

In this point, it should also be remindedthat Russia wisely refrains from referring internationally recognised maritime jurisdiction areas such as EEZ, continental shelf, and high seas for the Caspian Sea. Instead, it tries to implement a ‘common use on surface waters regime’ beyond territorial waters and fishery zone. By doing so, it avoids the rights given to states of sovereignty for constructing pipelines in the maritime jurisdiction areas in accordance withthe international law (UNCLOS, 1982) (Energy Charter Treaty, 1994). It already succeeded in implementing ‘common use on surface waters regime’ on the North Caspian by the bilateral agreements with Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. It expects the same regime to be also accepted by Iran and Turkmenistan with the signing of the legal status convention and became the general regime of the whole Caspian Sea restricting other littorals claim rights to lay pipeline by international law.

Since one of the arguments of Russia in order toblock the TCP is the lack of exhaustive agreement on the legal regime in the Caspian Sea, questions may arise about why Russia is pushing hard for the convention. It’s because Russia wants to guarantee with an agreement that no east-west pipeline project ever on the Caspian to be implementedwithout its consent. And this is the most appropriate time to tie up the deal in this way since their primary opponent in the region is as neutralised as never before. In Alexander G. Dugin’s words, who is an influential figure inKremlin’s policies: “The US is paralyzedfor the next three years. Good chance, we have to use it well.” (Dugin, 2017).Then,as mentioned above,the EU has a few serious problems to focus on as Brexit, irregular migration, and the rise of anti-EU political parties all weaken EU’s stand against Russia. Finally, Turkmenistan badly needs cash, and Azerbaijan lost Western support andcamecloser to Russia and Iran. So, Russia wants to benefit not only from the decline of Western effect in the region but also from the feeling of hopelessness and disunity among Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan; and it wants to have them put ink on a convention that obliges all the littorals’ consent for any pipeline project on the Caspian providing itself with the right to block any project in contrast with its interests.

Consequently, for the current situation, in the proposed legal status convention, Russia and Iran most probably still want to retain the right to veto any pipeline in the sea no matter from whose section it passes through (Bratchikov, 2017) (Rakhimpour, 2017). Russia and Iran try to achieve the veto right in a covert manner that can be readthrough their proposal on ‘previous versions’ of the draft legal status convention on which is elaborated above. We don’t have the latest draft which Lavrov commented on. Yet,it is one of the mainquestions of this article. But, we have the latest draft of EIA protocol which reflects the same stance of Russia and Iran. According to Bratchikov, Russia expects the EIA protocol to be signed before or simultaneously with the adoption of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea (Bratchikov, 2017). As a result, it appears that Russia and Iran would not give up their freedom to block any pipeline project bypassing them, so the previous proposals have probably been repeatedin the final texts of the legal status convention and EIA protocol.

- Conclusion

For so long, the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) project has been tried to be realised by Turkmenistan to diversify its customers and similarly by the EU to diversify its suppliers. The US has wanted the TCP to break Russo-Iranian energy dominance and their regional political influence. And Western energy giants have favoured it since it is the optimal east-west transfer method for Central Asian hydrocarbons.

On the other hand, Russia and Iran havenot wanted the TCP since it would result in tremendous deterioration on their economies, on Russia’s energy dominance over the EU and on its political influence in Central Asia. To date, they officially based their objection on the undefined legal status of the Caspian Sea and ecological damage the pipeline could cause.

Regarding China, there are both pros and cons of the TCP. Therefore, it appears that it would not take sides, but pursue a wait-and-see policy, instead.

As stated in the Introduction, the research was undertaken to guess as clearly as possible ‘the outcome of the upcoming summit in terms of Trans-Caspian Pipeline’, in order the public, academics and governments of related parties, especially of Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the EU, and the US to take proactive measures and to get out of the summit what they deserve according to the rule of law.Thus, the latest stances of Russia who drives the convention and its ally Iran were needed to be clearly definedtoguess the implications of the coming conventionregardingthe TCP.So, the statements of significant authorities who might best indicate the positions of their countries on the issue were investigated. The results supported the idea that the long-expectedlegal status convention will be used to ‘restrict the TCP’. Acknowledging the possible limitation of basing the argument on statements, although most of them were the statements of top diplomats representing their countries in the Caspian Convention Special Working Group; the result of the analysis was compared with the historical, economic, political and legal stances of Russia and Iran, and seen that it is in full compliance with them, too.So, it’s concluded that Russia and Iran would try to block the TCP using the forthcoming convention.

Then, the methods they would use to block the TCP were needed to be discoveredin order touse them to define counteractions which are deferredfor the next article. As for methods, their legal stance on the issue combined with the explanations of key persons suggested that Russia and Iran would refrain from mentioning a clear condition thatthe pipeline to Europe can be built only with the consent of all littoral states, as in Bratchikov and Rakhimpour’s latest statements; instead they would impose a convention having provisions in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) protocol to the Tehran Convention which covertly states that subsea pipelines across Caspian can only be built upon the approval of EIAs by all the affected littoral countries.

Then we have the question: why does Russia insist on the convention although it is already using the lack of the convention as an excuse for its opposition to the TCP? Becausenow is the best time to impose a convention that secures the obligation of its approval for any trans-Caspian pipeline project. It’s the best time since the Western effect in Central Asia is at its lowest and the feeling of misery and disunity among Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan is at its highest. In addition, it’s understoodthat not allowing the TCP is Russia’s state policy and it might even consider using military force to prevent TCP from being realised.

Besides, a number ofpotential limitations for the ‘guessing process’ in this research needs to be considered. First, a deterministic approach is used to guess the plan of Russia and Iran and the stances of the relevant parties in general. Certain causes are thought to lead the parties to take certain stancesand make their decisions tomaximise their owninterests. Second, the results are tried to be achieved using the latest information available in open sources. However, when the high rate of variability in political situations is takeninto consideration, for sure, there is always a possibility of change on the stances of relevant parties for the TCP before the summit took place. Yet,it canbe unequivocally statedthat the TCP is Turkmenistan’s indisputable right not only byinternational law but also in common sense.

Hopefully, the revealing of the Russo-Iranianplan for the TCPserves as a basis for public discussion, in-depth scholar works, and governmental decision-making on the subject to achieve equitable, proportional and fair terms on the upcoming Caspian Sea convention. From presidents to citizens, from diplomats to lawmakers, from journalists to scholars; it is everyone’s responsibility to prevent power politics from beating the rule of law behind the closed doors and helping Turkmenistan to implement the Trans-Caspian Pipeline project as its evident right. Next research into solving this problem is already underway, tofulfil the academic responsibility.

References

Azernews. (2017, December 20). EU Sees Trans-Caspian Pipeline As Complementary Element of SGC. Retrieved March 22, 2018, from Azernews: https://www.azernews.az/

Benner, T., Gaspers, J., Ohlberg, M., Poggetti, L., & Shi-Kupfer, K. (2018). Autharitarian Advance: Responding to China’s Growing Political Influence in Europe. Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute & Mercator Institute for China Studies.

UN. (2017, June). BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

Bratchikov, I. (2016, May 11). Interview of Igor Bratchikov, Head of the Russian delegation to the multilateral talks on the Caspian Sea, Ambassador-at-large of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation to “Caspian Energy” magazine published on May 11, 2016. (C. E. Magazine, Interviewer) URL: http://www.mid.ru/en/.

Bratchikov, I. (2017, December 12). Russia Offering an Elegant Solution for the Caspian Status. (C. E. Newspaper, Interviewer) URL: http://caspianenergy.net/en/.

Buckley, N. (2018, March 14). Gazprom Employs Risky Tactics in Dispute with Ukraine. Retrieved March 20, 2018, from Financial Times: https://www.ft.com

Council of the European Union. (2017). Council Conclusions on the EU strategy for Central Asia. Brussels.

Courtney, W. H. (2017, December 17). Unpacking Lavrov’s Claim About A Caspian Settlement. Majlis Podcast. (M. Tahir, Interviewer) URL: https://www.rferl.org/, Washington, D.C., USA: RFE/RL.

Cutler, R. M. (2017, January 9). China’s geo-economic influence is increasing in Central Asia but Russia remains main military-strategic power. Monday Talk. (M. S. Vicari, Interviewer) URL: http://www.vocaleurope.eu/.

Cutler, R. M. (2018, January 22). Commentary: U.S. Push Could Revive Turkmen Gas Hopes. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from RFE/RL: https://www.rferl.org/

Cutler, R. M. (2018, January 24). How Central Asian energy complements the Southern Gas Corridor. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from Euractiv.com: https://www.euractiv.com/

Darvish, M. (2018, January 24). Caspian Sea Water Transfer More Disastrous Than Nuclear Explosion. (T. Times, Interviewer) URL: www.tehrantimes.com/.

Dugin, A. G. (2017, November 6). Aleksandr Dugin’den Turkiye’ye Uyari. (N. Kocak, Interviewer, & Google Translate, Translator) URL: http://m/haberturk.com/.

EADaily. (2017, November 8). Turkmenistan’s gas deadlock: what Ashgabat to find in the embrace of Beijng. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from EADaily: https://eadaily.com/en/

EADaily. (2018, January 31). Gas genatsvales: Georgia promotes Turkmen gas in Europe. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from EADaily: https://eadaily.com/en/

ECOLEX. (2003, June 12). Convention on the Sustainable Management of the Lake Tanganyika. Retrieved April 21, 2018, from ECOLEX: https://www.ecolex.org/

Energy Charter Treaty. (1994). The Energy Charter Treaty., (p. Article 7).

ENTSOG-GIE. (2017). System Development Map 2016/2017.

Environmental Law Institute. (2009). Establishing a Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment Framework for the Mekong River Basin. Washington, D.C.: ECO-Asia and USAID.

Eurasianet. (2016, October 31). China Figures Reveal Cheapness of Turkmenistan Gas. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from Eurasianet: https://eurasianet.org/

Eurasianet. (2018, February 8). TAPI Enters Afghan Phase with Little Cash and Many Problems. Retrieved April 18, 2018, from EurasiaNet: https://eurasianet.org/

European Commission. (2017, November 8). Questions and Answers on the Commission proposal to amend the Gas Directive (2009/73/EC). Retrieved April 12, 2018, from European Commission Press Release Database: http://europa.eu/

European Commission. (2018). Gas and oil supply routes. Retrieved May 18, 2018, from European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/

Gazprom. (2018). Gas supplies to Europe. Retrieved April 20, 2018, from Gazprom Export: http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/statistics/

Geopolitica. (2013, December 25). Analysis of Post-Soviet Central Asia’s Oil & Gas Pipeline Issues. Retrieved March 22, 2018, from Geopolitica: https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/

Good Practices and Portfolio Learning Project. (2011). In Depth Case Study of the Caspian Sea. Institute of Asian Research at the University of British Columbia, Global Environment Facility Transboundary Freshwater and Marine Legal and Institutional Frameworks , Vancouver, Canada.

Hasanov, H. (2018, March 19). Turkmenistan seeks to build up economic ties with Russia: President. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from Trend News Agency: https://en.trend.az/

Hays, J. (2016). Natural Gas in Turkmenistan. Retrieved March 20, 2018, from Facts and Details: http://factsanddetails.com/

IFP. (2018, May 5). Iran Calls for Scientific Collaboration to Settle Caspian Sea Environmental Issues. Retrieved May 18, 2018, from Iran Front Page News: http://ifpnews.com/

Janusz-Pawletta, B. (2015). The Legal Status of the Caspian Sea: Current Challenges and Prospect for Future Development. Berlin: Springer.

Karayianni, M. (2018, February 8). Is the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline Really Important for Europe? Retrieved March 20, 2018, from New Europe: https://www.neweurope.eu/

Karayianni, M. (2018, March 14). The “expanded” Southern Gas Corridor: What comes after 2020? Retrieved April 10, 2018, from Neweurope.com: https://www.neweurope.eu/

Katzman, K. (2018). Iran’s Foreign and Defense Policies. Congressional Research Service.

Lemon, E. J. (2018, February 26). China, Russia and Security in Central Asia. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from Rising Powers in Global Governance Project: http://risingpowersproject.com/

Maritime Working Group. (2018, April 1). Caspian Sea Crisis Watch. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from Beyond the Horizon: http://www.behorizon.org/

Michel, C. (2015, July 10). What Azerbaijan and Central Asia Have in Common. Retrieved March 20, 2018, from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/

Mikheev, S. (2017, October 2). The Caspian fleet will build a new base. (N. Surkov, & A. Ramm, Interviewers) URL: https://iz.ru/650649/nikolai-surkov-aleksei-ramm/kaspiiskaia-flotiliia-pereedet-na-super-bazu: Izvestia.Ru.

Munich Security Conference. (2018). Munich Security Report 2018.

Nicholson, J. (2018, March 23). Russia ‘arming the Afghan Taliban’, says US. (J. Rowlatt, Interviewer) URL: http://www.bbc.com/

O’Neil, B., Hawkins, R. C., & Zilhaver, C. L. (2011). National Security & Caspian Basin Hydrocarbons. International Association for Energy Economics(2’nd Quarter), pp. 9-15.

Pannier, B. (2017, December 7). Qishloq Ovozi_Russia Says Caspian Legal Status Resolved, Agreement Ready For Signing. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from Radio Free Europe – Radio Liberty: https://www.rferl.org/

Pannier, B. (2017, December 10). Unpacking Lavrov’s Claim About A Caspian Settlement. Majlis Podcast. (M. Tahir, Interviewer) URL: https://www.rferl.org/, Washington, D.C., USA: RFE/RL.

Pannier, B. (2018, February 23). Afghan TAPI Construction Kicks Off, But Pipeline Questions Still Unresolved. Retrieved April 5, 2018, from RFE/RL: https://www.rferl.org

Pravosudov, S. (2017, November 7). Section of the Caspian Sea may Devalue the “Turkish Stream”. (M. T. Asia, Interviewer) URL: http://micetimes.asia/

Rabi, F. A. (2015, September). The company “Dragon Oil” – Turkmenistan: the positive experience of cooperation. (NEBIT-GAZ, Interviewer) URL: www.oilgas.gov.tm/en/

Rakhimpour, I. (2017, December 9). Iran’s Share on the Caspian is not 20% – Negotiations on the Delimitation Continue. (A. Ahtahi, Interviewer, & Google Translate, Translator) URL: https://www.isna.ir/news/96091809173/: Iranian Students’ News Agency.

Sadikhova, D. (2017, November 15). Rethinking Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan Relations. Retrieved March 3, 2018, from International Policy Digest: https://intpolicydigest.org/

SGC Advisory Council. (2015, February 12). SGC Advisory Council Joint Press Statement. Baku, Azerbaijan.

Shaffer, B. (2018, February 26). The Caspian Sea basin: lessons from recent major investments. Retrieved from Geopolitical Intelligence Services: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/

Shafiyev, I. (2018, March 10). ADB talks importance of Southern Gas Corridor (Exclusive). Retrieved from Trend News Agency: https://en.trend.az/

Shlapentokh, D. (2014, October 1). Russia and Iran Lock NATO Out of Caspian Sea. (J. Dettoni, Interviewer) URL: https://thediplomat.com/: The Diplomat.

Socor, V. (2011, March 8). Turkmenistan Demonstrates Commitment To Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from The Jamestown Foundation: https://jamestown.org/

Tahir, M. (2017, December 10). Unpacking Lavrov’s Claim About A Caspian Settlement. Washington, D.C., USA: RFE/RL.

Tehran Convention Secretariat. (2017, November 17). TC/COP6/3 (EN). Retrieved March 21, 2018, from The fifth Meeting of the Preparatory Committee for COP6 Documentation: www.tehranconvention.org/spip.php?article112

The Chronicle of Turkmenistan. (2016, October 29). Turkmenistan delivers the cheapest gas to China. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from The Chronicle of Turkmenistan: https://www.hronikatm.com/

Toktonaliev, T. (2017, May 23). Turkmenistan’s Growing Economic Crisis. Retrieved March 18, 2018, from Institute For War & Peace Reporting: https://iwpr.net/

Tsereteli, M. (2017, August 3). Better conditions for development of Trans-Caspian pipeline project exist today – expert. (K. Aliyeva, Interviewer) URL: https://en.trend.az/: Trend News Agency.

UN. (1998, July 6). Annex III (Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Delimitation of the Seabed of the Northern Part of the Caspian Sea for the Purposes of Exercising Their Sovereign Rights to the Exploitation of its Subsoil). Letter dated 13 July 1998 from the Permanent Representatives of Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, 10-13.

UN. (1999, November 28). Joint statement by the Russian Federation and the Islamic Republic of Iran on the proposed construction of a pipeline through the Caspian Sea. Letter dated 7 March 2000 from the Permanent Representatives of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General.

UNCLOS. (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea., (pp. Article 58, Article 79, Article 87, Article 112).

Votel, J. L. (2018). Statement Of Gen. Joseph L. Votel Before the Senate Armed Services Committe on the Posture of U.S. Central Command. Washington, D.C.

Zeynalova, L. (2018, March 23). European Parliament backs Southern Gas Corridor. Retrieved March 25, 2018, from Trend News Agency: https://en.trend.az/

End Notes

[1] Gunboat diplomacy can be defined as foreign policy that is supported by the use or threat of military force.

[2] Monopsony is a market situation in which there is only one buyer. The most commonly researched or discussed monopsony context is that with a single buyer of labor in the labor market. In addition to its use in microeconomic theory, monopsony and monopsonist are descriptive termsoften used to describe a market where a single buyer substantially controls the market as the major purchaser of goods and services.

[3] Swimming pool is the term used for the Caspian Sea by seamen in the Russian Caspian Flotilla. And the new cruise-missile carrying ships of Caspian Flotilla are referred by ‘the missiles’.

[4] He is talking about the Trans-Caspian Pipeline.

[5] In article 5 of the Espoo convention, it is written: “The Parties shall agree, at the commencement of such consultations, on a reasonable time-frame for the duration of the consultation period.”