Depuis l’annexion de la Crimée, l’OTAN et l’UE peinent à trou- ver la juste réponse face au regain d’agressivité de la politique étrangère russe. En dépit de sa condamnation unanime de l’agression, la classe politique occidentale n’a jamais été à même de forcer la Russie à rétablir le statu quo ante. La néces- sité d’une décision consensuelle n’a permis que de déboucher sur une série de sanctions économiques et financières, dont le seul résultat tangible est une inimitié accrue entre Moscou et les capitales occidentales. Le déploiement de l’OTAN dans l’est de l’Alliance atlantique, quant à lui, ne dépasse guère le cap du geste symbolique de solidarité vis-à-vis des alliés af- frontant directement les velléités expansionnistes de Moscou. Au-delà du constat d’échec, il faut s’interroger sur les causes et chercher les remèdes. Une part significative de la réponse se trouve dans la méconnaissance des réalités sociologique et politique de la Russie actuelle et dans notre allégeance extrême à l’éthique des valeurs libérales et démocratiques. Entre l’inten- tion de l’un et la perception de l’autre, la différence est parfois insurmontable et, en l’absence d’un accord, il faut peut-être se résigner à poursuivre un objectif réaliste à défaut de pouvoir réaliser l’utopie.

Sinds de annexatie van de Krim slagen de NAVO en de EU er maar niet in om het juiste antwoord te vinden op de toe- nemende agressiviteit van het Russisch buitenlandse beleid. Hoewel ze de agressie unaniem veroordeeld hebben, zijn de westerse politici nooit in staat geweest Rusland tot een herstel van de status quo ante te dwingen. Door de noodzaak om bij consensus te beslissen, kwam het nooit verder dan een reeks economische en financiële sancties, die enkel tot een grotere vijandschap tussen Moskou en het Westen hebben geleid. De ontplooiing van militaire middelen door de NAVO in het oosten van de Atlantische Alliantie reikt eveneens niet verder dan een symbolisch gebaar van solidariteit tegenover de bondgenoten die rechtstreeks blootstaan aan de expansiedrift van Moskou. De mislukking is overduidelijk, maar wat zijn de oorzaken en hoe kunnen we die verhelpen? Het antwoord schuilt grotendeels in de onwetendheid rond de sociologische en politieke realiteit van het hedendaagse Rusland en in onze extreme toewijding aan de ethiek van liberale en democratische waarden. Tussen de intentie van de ene en de perceptie van de andere is de kloof soms onoverbrugbaar en, in geval van onenigheid, is de keuze voor een realistische oplossing misschien beter dan het nastreven van een utopisch ideaal.

SETTING THE STAGE

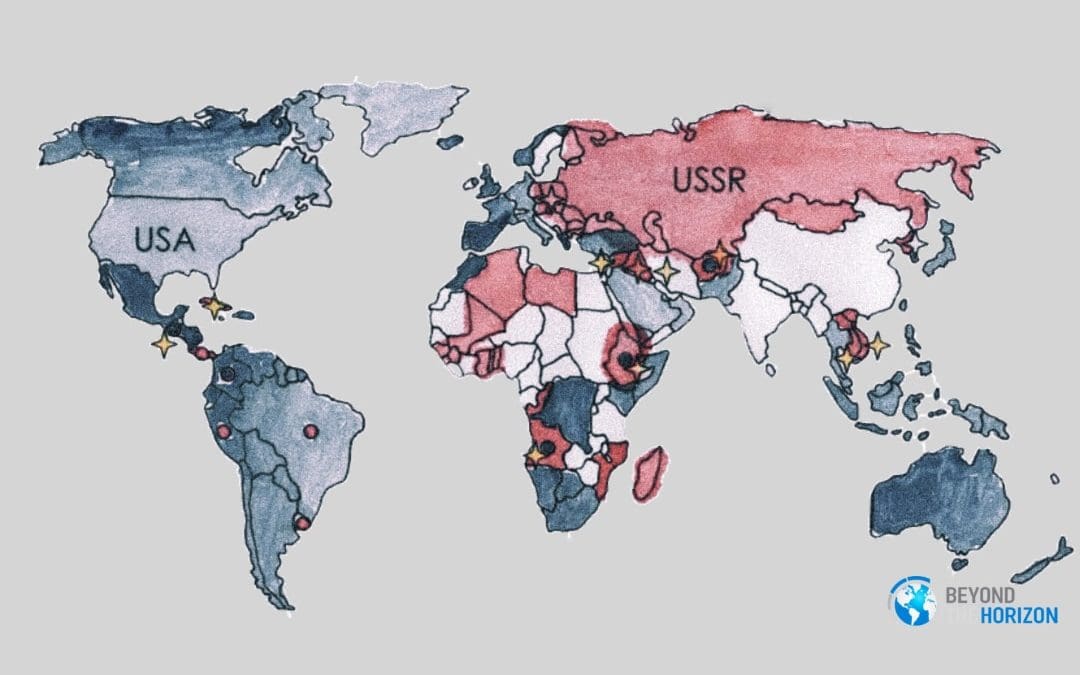

Since the illegal annexation of Crimea, the governments of NATO and EU countries have been struggling to define their attitude towards the Russian government. Whereas they unanimously condemned Moscow’s aggression, the sanctions imposed failed to reverse Moscow’s increasingly assertive foreign policy. The Putin administration has been using the resulting political isolation to justify an even more aggressive stance in other regions of the world, some of which are of direct concern to EU and NATO members.

Targeted economic and financial sanctions rather than a demonstration of military force are inspired by the Kantian liberal principles that govern our Western societies. Economic measures have a limited controversial impact on public opinions; they are easy to reverse and they preserve the long-term interests of Western companies.

However, the Russian government, which is the target of these sanctions, fails to perceive their relevance. Its realistic approach to international relations focuses on relative power positions that mainly materialise through military capacities

rather than absolute power increase through economic cooperation. That vision is complemented by the revival of Neo-Eurasianism, an ideology that seeks to restore Russia’s position as the dominant power on the Eurasian continent and that has seduced a significant majority of Russians.

Western governments have only timidly adapted their military doctrines but have largely failed to meet the reality check. Defence investments and deployment of military forces continue to be hampered under fallacious excuses of budget constraints. Means are no longer being adapted to the security challenge, but levels of ambition for a deterrence posture are downgraded to fit self-inflicted technocratic financial parameters. As a result, the pale military response to Russia’s increasingly assertive stance looks more like a political statement than a credible deterrence. The NATO troops deployed in the east of the Alliance constitute, at best, a trip flare, but they are no realistic match for the tens of thousands of Russian troops stationed at the Alliance’s border.

More than two years after the annexation of Crimea, we should evaluate the choices made by Western governments and draw conclusions as to future postures to adopt. Is it still worth investing efforts in trying to reach an economic and democratic peace with Moscow or should we fall back on the kind of peace that stems from a balance of powers as we had during the Cold War? Without being the West’s preferred option, the latter solution could at least provide a return to stability on which future relationship models could then be elaborated.

A common mistake that biases many analyses of Moscow’s political posture stems from a wrong assumption that Western benchmarks are universal and that similar economic realities produce comparable effects in different political systems. The differences between liberal democracies and Russia reach much further than what Western politicians like to believe, not only regarding political approaches to international relations, but more fundamentally in terms of anthropological heritage, social and behavioural psychology, and ideology. In order to understand how this affects Western policies towards Moscow, three main elements need to be considered. Firstly, we must understand why centrally planned economy changed to a capitalistic model and analyse how this affected the relations between Russia and the West. Secondly, we must proceed with an emphatic analysis of Russian sociological and political realities and distinguish which elements are political and therefore subject to change, and which elements derive from a common national feeling and world vision that transcend successive political systems. Thirdly, the effectiveness of Western foreign policies must be evaluated against the desired end state that they pursue and their influence on Russia’s attitude rather than against their compliance or not with Western political correctness.

THE ROAD FROM RESTORED RELATIONS TO REALPOLITIK

The year 1991 saw the dissolution of both the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union. For Western political elites, it was the evidence of the supremacy of Western democracies over authoritarian communist regimes, and they were convinced that the Western model would henceforth prevail on both sides. In his book The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama argued that “liberal democracy may constitute the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the final form of human government”. The Western orientations followed by many former communist states that used to belong to Moscow’s sphere of influence added to this conviction. The sudden disappearance of the spectre of a third world war had created a new relational context, and neither side was well-prepared for it. On the Western side, Cold War politicians thought that time had come to yield the peace dividends of their years-long investment in defence and deterrence. Many countries abandoned conscription, units that had been deployed to West Germany were disbanded or merged, resulting in much smaller armed forces. Defence budgets were stripped, and even the relevance of NATO was openly questioned. As the Cold War had never materialised into an armed conflict, it also terminated without the conclusion of a peace treaty designating a victor and a loser. Instead, relations between Russia and the West evolved from a confrontation into a partnership almost from one day to the other. Western economies were eager to invest in the reconversion of their former enemy, and a new logic of cooperation imposed itself almost overnight as a new paradigm for East-West relations.

On the Russian side, the challenge to transform the political and economic structures of the Soviet legacy was enormous. At the beginning of his mandate, Boris Yeltsin endeavoured to transform the political culture among Russian elites to enter into a partner relationship with the former enemy. In fact, Russia did not have many alternatives. It desperately needed to close the enormous technological gap left by the failed centrally planned economy and to import the capital and the know-how that it had been unable to generate from inside. The adoption of the Western capitalistic model was more dictated by a state of necessity than a deliberate choice to embrace the Western socio-economic system altogether. The split between the economic and sociological dimensions would soon evolve into devastating political antagonisms.

Yeltsin’s allegiance to liberal orientations encountered growing enthusiasm in the West, but it came at a high price in Russian domestic politics. The right-wing conservative class blamed him for abandoning Russia’s national interests and for submitting to the will of the US. As opposition grew and in order to safeguard what remained of popular support, Yeltsin had to sacrifice his pro-Western Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev in January 1996. Yevgeniy Primakov, who replaced him, was a pure “realpolitiker” who advocated multilateralism as an alternative to American unilateralism. Many analysts consider his arrival as a critical waypoint in Russia’s foreign policy. Soon after, the appointment of Vladimir Putin as Prime Minister in 1999 and his election as President in 2000 would cause Yeltsin’s pro-Atlanticist policy to stall, then to be reversed.

WHAT IS ON MOSCOW’S MIND

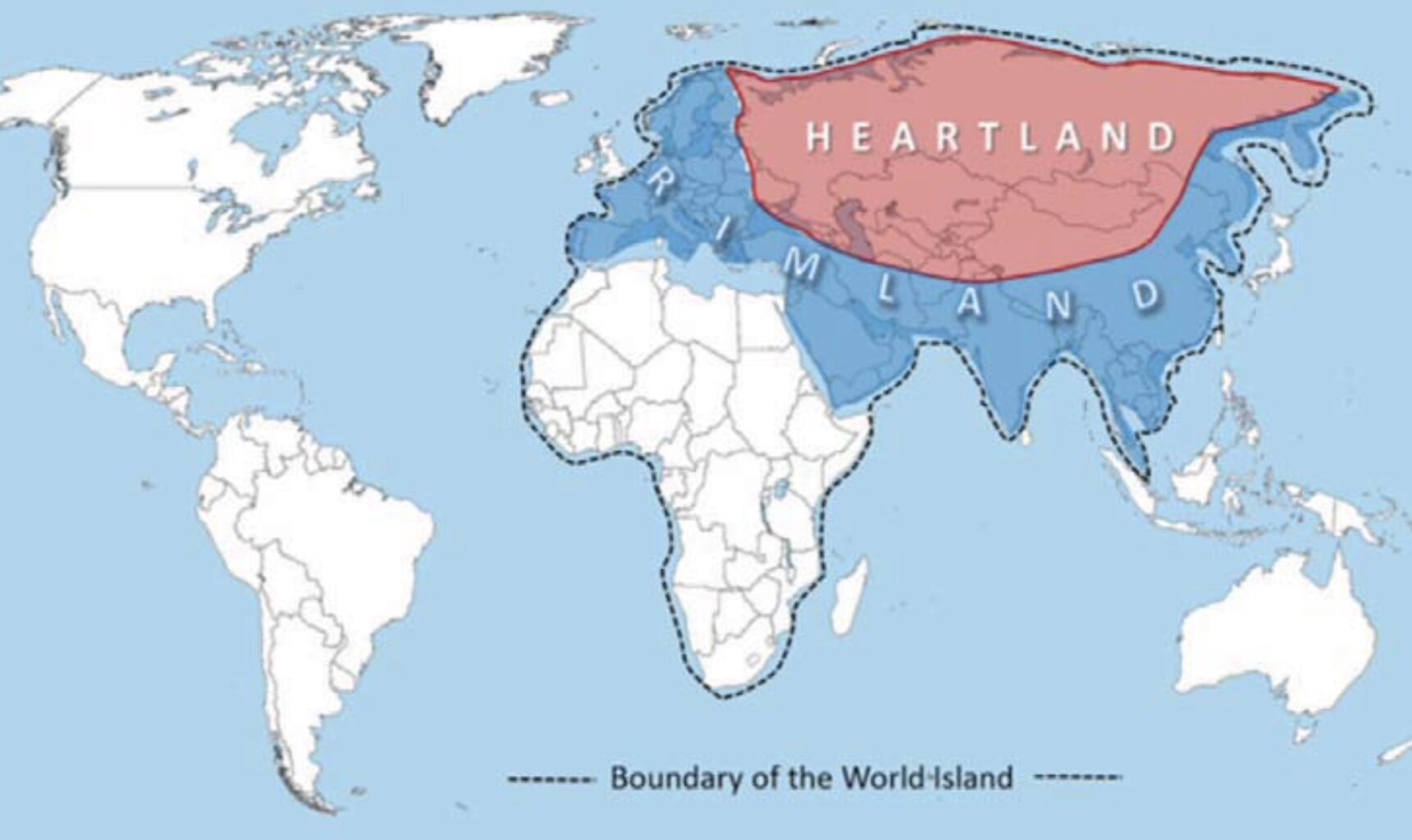

The revival of Russian nationalistic feelings paved the way for political formations, such as Aleksandr Dugin’s Eurasia Party. Building on people’s frustrations to see alien cultures invade their lives, Dugin challenged the Western-oriented transformation of the Russian economy and society and advocated a return to core Russian traditional values, such as patriotism, asceticism, honour, and loyalty. In his book The Last War of the World Island, he sets out a widely shared Russian vision of the world. Inspired by Halford MacKinder’s Heartland Theory, he rules out any possibility of convergence between Russian and Western societies. He argues that the cultural and sociological antagonisms that oppose tellurocracies or land-based civilisations and thalassocracies or sea-based civilisations are so fundamental that the two are doomed to find themselves in a perpetual situation of conflict. One of the mutually exclusive characteristics is the diverging understanding of social relations. Sea-based civilisations tend to consider the individual as the basis of the social system and define the group as a voluntary gathering of individuals, based on shared values and agreed behaviours. In land-based civilisations, the interest of the group tends to prevail over the individual. In order to safeguard the homogeneity of the group, a certain level of coercion is perceived as normal and acceptable.

Neo-Eurasianists considered the collapse of the Soviet Union and the shift towards thalassocratic values as a catastrophe. It was seriously jeopardising the cohesion of the tellurocratic project to control the Heartland and to project their influence on the Rimland to gain control over the World Island. The shift to the West was felt as the unconditional surrender of an entire civilisation, with its principles, its values, and its historical heritage.

At first, Neo-Eurasianism was not the motivator behind the political action of Russian elites. Their primary objective was to consolidate their position at the top of the state and to use their power for their personal benefit. Neo-Eurasianist theories and their romantic narratives, however, conveniently provided an attractive facade to gain public support. As years passed, Neo-Eurasianism became a self-fulfilling prophecy. From a convenient alibi, it gradually became the defining element of Russia’s foreign policy. In 2007, Vladimir Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, which announced the return of the immutable tellurocratic project to control the Heartland and its immediate vicinity, was a clear manifestation of Neo-Eurasianist influence.

A better understanding of Neo-Eurasianism leads to a double conclusion. Firstly, Russia considers itself in a state of conflict with the Western world. It does not seek any form of cooperation with it, and will not do so in the foreseeable future. Secondly, Russia, as a nation, reacts to very different sociological triggers; its people live according to their own values that do not match those that Westerners wrongfully believe to be universal.

With the arrival of Vladimir Putin, Russia reverted to a primitive form of political realism. Unlike the defunct Soviet Union, which pursued a more neorealist policy, leaving some room for supranational institutions, today’s Russia bluntly disregards international law as soon as it is detrimental to its interests. Western governments that engage in international agreements with Russia will therefore only find themselves constrained by their unilateral allegiance to supranational institutions or international treaties. Another worrying manifestation of primitive political realism that resurged in Russian politics is the naturally confrontational character of relations between nations. Realists do not believe in the virtues of democratic or commercial peace. They do not even consider peace to be a desired end state. Hobbesian peace, in its narrow acceptation of absence of war, is merely a temporary condition resulting from a balance of power. As soon as one of the parties has sufficient superiority to defeat its neighbour, war becomes inevitable.

In Machiavelli’s quote “the end justifies the means” political realism can only address the “means” not the “end”. Linking the Neo-Eurasianist vision of Russia’s place in the world order with its political realism provides a fairly accurate answer to the double question of ends and means.

WHERE THE WEST WAS WRONG

In their reaction to Russia’s aggressive stance, Western governments made a number of miscalculations. Some were dictated by economic opportunism, some others by overconfidence in the alleged universality of Western liberal values, but most of them were the result of a plain ignorance of Russia’s anthropological, sociological, and political realities.

Instead of picking up the early signals of the Russian-Georgian War in 2008 and adapting their security policies, Western decision-makers seemed more concerned about securing their economic relations with Russia. American and European investments in Russia, which were supposed to foster peace through economic interdependence, above all, limited the ability and the will of Western governments to adopt a firmer attitude. In the years that followed, while Russia embarked on an unprecedented remilitarisation programme, NATO and EU countries further depleted their defence capacities. Disregarding their primary mission of territorial defence, many Western nations transformed their military in smaller projectable forces adapted to counterinsurgency operations on distant theatres, but no longer fit for high-end warfare at home.

When Russia annexed Crimea and launched its hybrid proxy war in Eastern Ukraine, the West mainly reacted with economic sanctions and targeted measures against individuals. However, while making sense for Western minds, these measures blatantly ignore the fundamental difference between Western and Russian socio-economic models. Whereas growth parameters are essential indicators in liberal economies, they do not resonate with the same force in a system that does not recognise economic activity as a primary factor of power. Instead, the Russian government instrumentalises the sanctions to blame its degraded economy on outside factors rather than its own poor governance. The sanctions also impact Russian government circles in an asymmetric way, affecting mainly those who rely on foreign trade to uphold their level of influence. In a governing apparatus that is composed of ideologists, oligarchs and the Orthodox Church, the sanctions, therefore, reinforce the position of the hardliners to the detriment of the more moderate forces. An even more perverse side effect is that, deprived of foreign financing, what is left of Russia’s heavy industry is gradually returning under state control. A shift towards more military industry should come as no surprise.

The other component of Western sanctions targets individuals who have a direct responsibility in the Ukrainian conflict. Again, this may seem fair and meaningful to a Western mind that considers the fate of an individual person as a concern for the entire group. It is, however, much less the case in Eurasian civilisations, where the interest of the group prevails over the individual. Actions affecting individuals are not perceived as an existential threat to the group and will not influence its behaviour as a whole. Economic sanctions and targeted individual measures do not impress the Russians. After decades of Soviet Union, resilience in front of hardship and resignation in front of individual persecution have become second nature in Russia.

Russian realists find military power a far more reliable benchmark in international relations. While economic sanctions can be mitigated by reorienting trade towards other markets, by using financial reserves or counting on the resilience of the people, no economic action has ever stopped an invasion by military means. Military power is a realist’s natural instrument in international relations. It first serves to defend the state against external aggressions by establishing a mutual deterrence through a balance of power. The ensuing peacetime serves to consolidate positions and to reinforce military capacities. As soon as a sufficient level of supremacy is reached, the realist will use his power to gain control over his neighbours.

On the military side, Western reactions to Moscow’s aggressive posture remain far below par. The assurance measures aimed at demonstrating solidarity with NATO’s eastern allies constitute, at best, a political signal, but they are nowhere near to creating the balance of power that a realist would recognise as such.

Even the adaptation measures creating an enhanced NATO Response Force and the symbolic deployment of a few NATO battle groups are unimpressive in comparison with Russia’s military build-up and its Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD) installations on the periphery of its territory.

Many seek to justify the limited military presence of NATO troops in the east of the Alliance by invoking the provisions contained in the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation that dates back to 1997. This justification, however, lacks relevance when considering how obsolete this text has become. In the twenty years of its existence, Russia has violated almost every single of its clauses. More interestingly, the paragraph that is supposedly preventing the stationing of substantial combat forces starts with an explicit conditional provision: “in the current and foreseeable security environment”. Today, nobody can sustain the claim that we find ourselves in the same security environment as twenty years ago, nor that its evolution was even foreseeable. However, the choice for a deployable response force rather than a significant permanent forward presence remains more attractive from a Western perspective. It better fits the budget constraints and can theoretically deploy to any theatre, which makes it more acceptable for countries that are geographically more remote from a potential Russian threat. Moreover, it looks less aggressive than a permanent deployment, which Western politicians wrongfully believe to be an advantage in their relations with Russia. To a Russian political observer, the numbers are unimpressive, and he knows that it will take days to decide on the activation of the response force and weeks to fully deploy it.

CONCLUSION

The short conclusion is that the economic sanctions and targeted individual measures fail to influence Russia’s foreign policy and that the adaptation of military doctrines does not create the regional balance of power that could lead to an absence of war through mutual deterrence.

The highest priority for Western governments should be to gain a better understanding of Russia as a nation and to recognise the fundamental differences between Western liberal democracies and Russia in political, cultural, and sociological terms.

Western policymakers should refrain from trying to export their liberal eco- nomic model to states that do not recognise the value of it or that have no other option than accepting it when they find themselves in urgent need of economic development. They must realise that democratic and economic peace theories can only function among states that recognise the prevalence of the liberal value system. Even more importantly, they must understand that the freedom, which is inherent to liberal government systems, requires a strong state that is capable of defending itself against outside threats.

In response to Moscow’s aggressive posture, Western politicians should adapt their actions to Russian perceptions, rather than seek compliance with their own ethical norms. Measures targeting individuals do not produce any effect, except giving a good feeling to the one who inflicts them. For a Russian observer, collective measures, even if they were of a lesser magnitude, would yield a much stronger effect. Travel restrictions could be imposed against specific categories of people rather than individuals. Trade sanctions should be re-evaluated. Restrictions should primarily deprive the Russian industry of technologies that can be used in the defence sector and from financing sources that will inevitably be used, through communicating vessels, in additional military capacity building.

Instead of trying to convert Russia to a liberal democracy, which is doomed to fail, efforts should focus on creating a pacific coexistence. The best variant of peace that we can hope for is based on a balance of power at a global, but also at a regional level. This can only be realised with tangible assets that Russia would recognise as an actual deterrence rather than some subliminal political message that only resonates in Western minds. It will be necessary to deploy and sustain a credible forward military presence in countries that share a common border with Russia or its allies. Such a force would not only constitute a credible deterrence, but would also reduce the exposure to subversive or hybrid actions that remain below an Article 5 threshold.

Western democracies can only sustain their liberal socio-economic model if they restore, in the short term, a credible military capacity to defend themselves against realist threats that develop at their borders. Defence is not just a component of the liberal system; it constitutes its ultimate protection. Investments in military capacities should, therefore, be withdrawn from calculations of budgets and considered separately when establishing economic indicators. In the end, if a system is unable to defend itself and to ensure its survival, its economic indicators will no longer make any sense anyway.

Accepting a new status quo based on a Hobbesian rather than Kantian peace

would at least bring back some badly needed stability. The new status quo would be different from what we have witnessed during the Cold War, but some aspects would be similar. Economic interaction would be limited and subject to security imperatives. NATO would need to place collective defence back at the top of its priority list. It would also need to uphold its credibility by admitting new members and be robust enough to do so, even if it is unacceptable from Moscow’s perspective.

This article was first published in December 2016 on Het Belgisch Militair Tijdschrift – Edition 13

Lieutenant Commander (R) Kurt Engelen is a lecturer in international politics at the Riga Graduate School of Law and a researcher in Russian politics at the Center for Security and Strategic Studies of the Latvian National Defence Academy. Assigned as a staff officer to the Belgian Military Representation to NATO, he represents Defence in the Military Committee’s working groups on cooperative security, training and exercises, air and missile defence and operations in the Balkans.