Turkey has been a key ally for the western world for decades. Once a role model democracy in the middle-east and formidable NATO ally with a stand out armed forces in the region, Turkey safeguarded the southeastern flank of the alliance with confidence. However, all these have been changing recently.

Since the abortive coup attempt of July 15, the government narrative towards the western world turned hostile. Although there was (and still is) a plethora of unanswered questions surrounding the events of the July 15, government was quick to point the finger to NATO and USA, despite lack of any evidence. The rise of anti-American and anti-Western “Eurasianists” within Turkey’s officer corps coupled with Erdogan’s tight maneuvering space in the western world due to Turkey’s slide away from democracy and human rights violations, brought Ankara to the brink of a new era marked by an ‘Axis shift’ towards Moscow [1]. Clear evidence of this digression is the new Russian Air and Missile Defense(AMD) system acquisition on the table.

Source: Sputniknews

Turkey aims to bolster air defense with Russian built S-400 Triumf (NATO identifier SA-21) AMD System and transform its air defense architecture, which currently depends heavily on aircraft. Turkey has tried to close air and missile defense gap with HQ-9, S-300VM, Eurosam SAMP/T acquisition attempts before. Previously, a team of Air force and Ministry of Defense experts, after a long and strenuous process concluded that Chinese HQ-9 and Russian S-400 systems were far more superior as standalone systems compared to others. A contract for Chinese HQ-9 was pursued in a lukewarm manner, stretching Chinese patience for years, until the deal was finally called off on November 2015 [2] with the assertion that Turkey would now pursue building an indigenous system. After 15 July, Turkey turned a cold shoulder on allies and S-400 deal became a symbol of Turkey’s newfound inclination towards Russia.

However, Turkey has been a crucial NATO ally for more than half a century and part of the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense (NIAMD) for decades. NIAMD is an essential, continuous mission safeguarding alliance territory, populations and forces against any air and missile threat and attack, which was proven effective and deterrent on various crises [3]. NATO agreed to boost Turkish missile defense systems, deploying troops in 2013 against the threats in the southeast. AMD systems and operators from various NATO nations were able to conduct the NATO Support to Turkey mission in an integrated manner. This augmentation was only possible due to the strict standards NATO adheres to which are geared towards achieving interoperability. The North Atlantic treaty neither promotes nor compels the allies on systems to be procured, however, robust NATINAMD system derives strength from interoperability, and it is assumed at strategical level that each new system will be another link added to the chain with maximum compatibility. With Turkey being so aggressive to pursue non-western systems like S-400, the strategic assumption of interoperability is being by-passed which could be interpreted as a political backstabbing and would introduce drawbacks at the operational and tactical level.

Breaking the ranks of NATO is a long-pursued dream for Russia, and S-400 deal could be an initial step paving the way for cracks in the alliance [4]. Nevertheless, it is not a secret that ex-Warsaw pact nations have Russian built systems and another NATO member, Greece has adopted (albeit through a convoluted manner) S-300 system when Turkey drew a casus belli line blocking the original shipment to Cyprus. Greece could not integrate the S-300 system to the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense System (NATINAMDS)[5].

With the lack of Recognized Air Picture and Link-16 (NATO’s military tactical data exchange network), the standalone system provides limited benefit to owner.

No visible crack formed on the alliance and on the contrary, some NATO nations together with partners like Israel carried out exercises to master tactics against this SAM system, a rare training opportunity[6]. Other systems like Greek SA-8 are too minor to change the equation.

Despite the transaction’s large potential implications at the political level, Russia seemed to be surprisingly reluctant at first. This indisposition was eased when the sides came to the final stages of signing a contract, with some open technical issues, according to Russian press [7]. One of those technical issues is likely to be the payment. Russia wanted the payment up front on the $2.5 billion deal and Turkey appears to be a few billion dollars short. However, there has been a series of statements especially on the Russian side that both sides were very close to signing off. At the time of writing of this article, Turkish President and Putin’s adviser for military and technical cooperation had made statements that the deal was done and a down payment was made [8]. Nevertheless, there is a long time until the system treads on Turkish soil. The shipment may be delayed or called off due to political or other reasons such as lack of full payment etc. Iran signed a similar deal in 2007 for S-300 procurement [9], and the shipment had to wait until October 2016 due to sanctions [10]. No matter what happens in the end, it is certain that this deal would be opening a new era in Turkey’s stance in the international chess table.

On the technical side, S-400 acquisition is more problematic than it looks. Even though its advertised features are far more superior to other SAM systems, S-400 is not combat proven. Surprisingly, the presence of S-400 or S-300 systems in Syria did not hamper US operations. When a Syrian army SU-22 jet dropped bombs near the US-backed forces, it was immediately shot down by a US F/A-18E Super Hornet on June this year [11]. On another occasion, US Armed forces successfully launched a cruise missile attack against Shayrat AFB on 7 April 2017, destroying about 20% of the Syrian government’s operational aircraft [12]. The mythical Russian Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD) was nowhere to be seen. It should be pointed out that whether the lack of interference was due to short notice of the strike given through a pre-existing “deconfliction” channel [13] or the incompetency of the air defense systems is unknown. While there is no evidence to support latter, Russian side stayed defiant in the face of the unexplained “lack of interception”. According to a Delovaya gazeta Vzglyad article titled “Russian S-300s have closed the sky of Syria from American cruise missiles” on October 2016 [14], Russian Defense Ministry representatives bragged about the range of S-300 and S-400 missiles and capability to ensure the security of bases in Syria. This statement was underpinned by Lieutenant-General Aitech Bizhev, who stated they would shock any potential aggressor daring to brandish swords, by knocking them out from the game completely. One way or the other, the systems obviously failed to deter or defend [15].

Delving into Turkey’s troublesome neighbors reveals that the real threat is the BMs. Turkey has an alternative way to carry out air defense i.e. with aircraft, but not one for BMD (Ballistic Missile Defense). Actually, it would not be a hyperbole to say adversaries’ BMs (Ballistic Missile) are creating an asymmetry for Turkey; therefore, it is what Turkey should focus on. Turkey is badly mistaken if the intent is to do BM defense with S-400, since it only protects 60 km radius, which under realistic conditions would shrink even more considering the lack of a cueing radar. The reduced range would render the system capable of point defense only, making it comparable to NATINAMDS integrated Patriot-PAC3 and S-300. Considering that any BMD system can be overwhelmed by “raining missiles”, there is only one-way to defend: To Deter. One should be able to counter an attack either with devastating force and making it a “lose-lose more” game or by erasing the notion of attack by baring nuclear fangs. In Turkey’s case, NATO’s IAMD and presence of nuclear weapons in Incirlik act as a symbol of the American commitment to Turkish security [16]. Thinking a single system acquisition would solve all problems is no better than burying one’s head in the sand. The number and the price tag of BMD systems, or their interceptor missiles are nowhere comparable to that of ballistic or cruise missiles. The firing angle, terminal speed, apogee of the BM as well as many other parameters may render a missile out of intercept envelope, even if the missile is inbound to its defensive footprint. A number of low flying cruise missiles cloaked by terrain and earth’s curvature would very possibly knock down a multi-billion-dollar system, and lack of a datalink makes it easier. There is no defense system that is impervious, and judging by today’s threat environment, allied solidarity and cohesion mean more when countering asymmetry.

It can be concluded that BMD is a purely political issue due to limited assets: the aim of a NATO missile defense is to provide full coverage and protection for all NATO European populations, territory and forces with very limited number of resources. Unfortunately, the scarcity of resources coupled with increase in threatened territory due to growth of missile ranges, means that allies will race for resources if things heat up and NATO adapts more vigilant Ballistic Posture Levels. At this point sword crossing between the allies would not help to win the game. The backbone of NATO Ballistic Missile Defense system is US European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) contributions to NATO and alliance is dependent on USA for space based early warning, X-band radar and SM-3 interceptors. Turkey, along with other NATO nations, receive Shared Early Warning (SEW/SEW+) information around the clock, which is vital for passive defense. It also gives early warning information to next phase of detection and tracking systems. The most important part of the kill chain is the AN/TPY-2 radar system located in Turkey, which provides cueing data to all NATO based missile defense systems. With the absence of datalink, operators may be able to see the complete air picture with heritage systems but the system will not have access to the combat management software that cues the missile defense interceptors and there will be no automatic data transfer [17]. Considering the fact that S-400 envelope is 60 km – with cueing, without cueing it will be less, it will provide point defense only to a limited area. If Ankara’s aim is to have better missile defense, THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) offers more. In fact, Turkey requested to have a battery deployed during the early stages of Syrian crisis, but was turned down by the USA.

The S-400 system would provide very little for missile defense but given the assumption that it performs as advertised, it will be beneficial as an air defense system. Currently, the hole in Turkish air defense wall is so big that anything would help in filling out the gap. The marginal gain will be substantial but not as much as it could be, since S-400 will not be integrated to the air defense network and therefore will lack some capabilities such as IFF.

There are many points unknown about the details of the procurement, such as system components, number of missiles to be purchased and other details. However, it wouldn’t be imprecise to assert that adapting to Russian doctrine would be challenging since the way they fight, and organize is quite different than NATO counterparts. Added the lack of integration, problems arise in main coordination areas such as Fighter – SAM and upper tier-lower tier missile intercept. The system is to be produced no earlier than a year, if the deal goes through. Brainstorming of training for the system and logistics should have already started by now, since a complete about-face in doctrine will require a long time in adaptation. The Russian addition will outstretch the logistic chain and make the footprint larger, since Turkish arsenal consists of western systems. Turkey is going to have to face a long list of problems, even in basic issues, ranging from language barrier to truck spare parts. The system will remain purely autonomous, preventing; timely alert and warning, early ID – tracking and leaving many gaps in self-generated air picture to adversary leakers, thus rendering it vulnerable to low level cruise missile or ARM (Anti-Radiation Missile) attacks. Russian command and control system is incompatible with current Turkish systems, which would hamper, centralized planning and direction. In the air defense role, it would have tactical issues such as Fighter-SAM coordination or handover problems to other air defense resources due to incompatible command and control system.

As a result, the system would fail to act as an effective layered defense system due to blood incompatibility with other western systems.

It is also unknown to public what kind of limitations Russia would put at the S-400 export version to Turkey. When it comes to technology transfer, Moscow is reluctant. They stated that there are various levels of tech transfer [18] and they would more likely agree on production in Turkey [19]. As Turkish defense industry is at the shrubs level in the tech tree, it would be elaborately naive to think that Russia would be willing to transfer the secrets of its most sophisticated air defense system. On the other hand, Turkish claims to make its S-400 compatible with NATO systems by making an interface program through IFF coding by Turkish defense company ASELSAN, is misleading if not completely false [20].

NATO would fear that Moscow could use the S-400 as a Trojan horse to compromise NATO systems.

Therefore, it would seclude S-400 from its tactical datalink, the air picture feed and encrypted IFF codes. As a result, the risk of blue-on-blue engagements will increase and could render fighter SAM coordination almost impossible. Turkey would have to integrate national IFF and datalink, which will take years after system acquisition, without any guarantees for success. On the other side of the medallion, the same risk of disclosing confidentiality applies to Russia, too, reminiscent of what happened when East Germany joined west with MiG-29s. It wouldn’t be surprising if Turkey ends up with a black-box, restricted version of the system, suiting Russia’s interests without compromising national security. This assumption is backed up by Colonel Murakhovsky, citing that the export models would be significantly inferior to those in the arsenal of Russian Armed Forces, and would not include the latest cutting-edge technology [21].

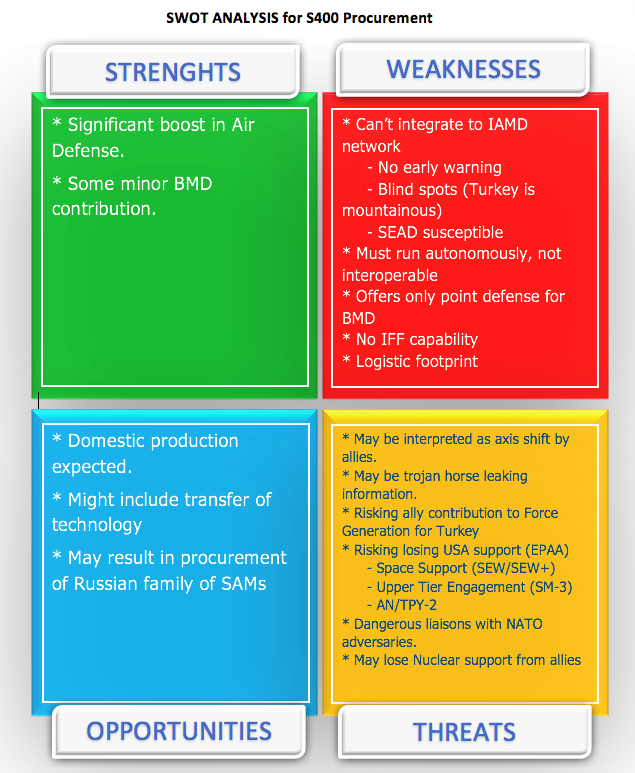

Turkey clearly wants to think outside the box on tactical level for procurement, but must be ready for repercussions at strategical and political level. It is no secret that under the scope of historical determinism, Russia has been a major security concern of Turkey, threatening her for territory and revision of the status of the straits as late as 1940s. The North Atlantic Alliance not only provided balance of power in the region, but also swore to protect from BM attacks, countering asymmetry from Syria and Iran. Turkey must calculate the trade-offs in acquiring S-400. SWOT analysis below, summarizing high level arguments presented on this paper, clearly depicts that Turkey has much to lose by developing tensions with the USA, the sole provider of many key elements of missile defense, and NATO.

The further Turkey shifts axis from NATO to Russia, the more it is likely to lose on the missile defense bargain at NATO Headquarters considering high demand for coverage and ever-growing proliferation. Turkey should not risk what is already at hand by raising suspicions about its commitment to the alliance, which in return will surely result in reluctance of the allies during force generation. That is of course, providing that Turkey wishes to stay in the Western world. If Turkey proceeds on the current inclinations and actually unmoors from current axis, it is going to be a completely new story to begin with.