1. Introduction

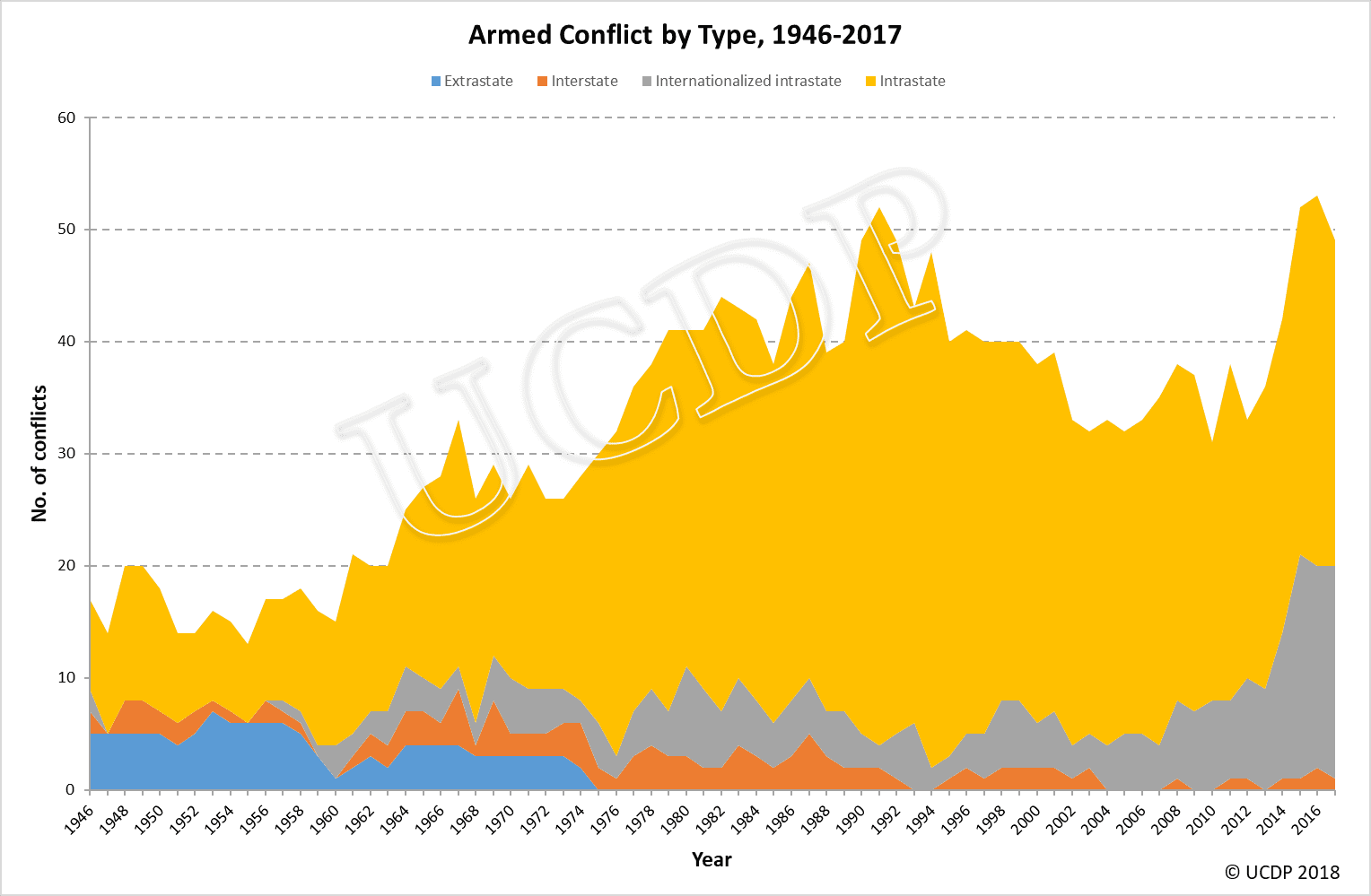

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), 48 of the 49 active conflicts in 2017 were fought within the boundaries of a state between government and opposing groups. 19 of these conflicts were internationalised (40%) with intervention from other states in the form of troops to at least one of the sides. (Kendra & Siri Aas, 2018). The number of internationalised conflict would be higher if foreign intervention is construed in broader context to include economic, logistical, and diplomatic assistance or sanctions applied to influence the outcome of the conflict in addition to exertion of military power.

(UCDP, 2018)

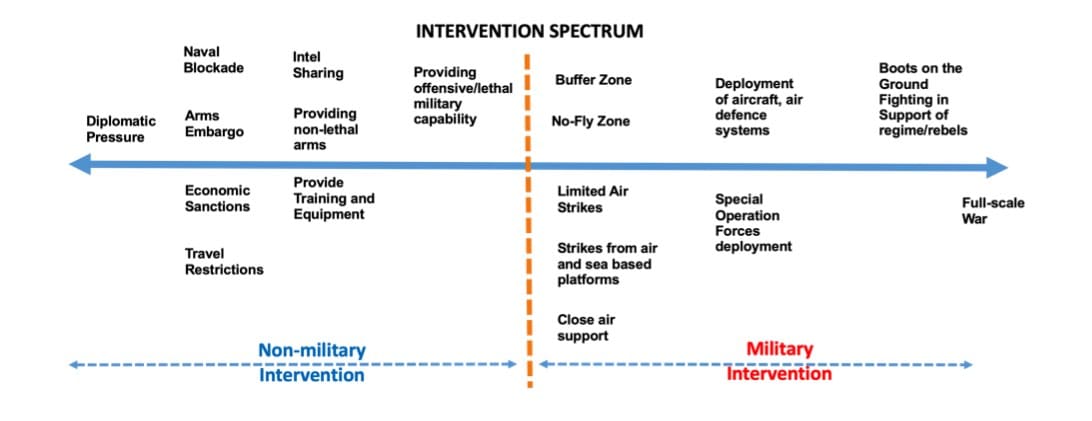

As internationalised civil wars constitute significant aspect of international politics, potential drivers of third party interventions into intra-state conflicts and more specifically civil wars have been widely researched within International Relations (IR) theories. Realism, liberalism, and English School theories provide different frameworks with varying power to explore and explain why third parties intervene into intra-state conflicts and more specifically civil wars. Is it exclusively national interests, values, or both that drive the intervention decision? How can we explain major power`s selective interventions and use of different tools from the intervention spectrum ranging from diplomatic pressure to boots on the ground fighting in support of regime or rebel groups to influence the outcome of a civil war? This study looks into different perspectives provided by three distinct IR theories regarding third-party interventions to civil wars.

(Boke, 2017)

2. Realism and Intervention

Realist tradition describes international relations as conflict between states in which the interest of each state excludes the interests of any other. Under realist perspective states are free to pursue their goals without any kind of moral or legal restrictions (Bull, 2012:23-24).

As a classical realist, Morgenthau attributes the objective laws of politics to human nature. He claims that the statesman makes his decision regarding foreign policy issues on the basis of rational choice theory which minimizes risks and maximizes the benefits. The decisions are made based on the assessment of how that policy might affect the power of the nation. So the statesman is believed to think and act in terms of interest defined as power (Morgenthau, 1985). Maximizing the state interest in an anarchic and threatening international environment is seen as the only option to ensure survival of the state.

Structural realists on the other hand believe that prevailing anarchy within the international system urges states to maximize their relative power to ensure survival and security. Structural realism has two main strands: defensive and offensive realism seeing states as security and power maximizers respectively. Defensive realists such as Waltz argue that states are satisfied when they obtain enough power to ensure their security and survival whereas offensive realists such as Mearsheimer posits states are willing to acquire as much power as possible and they make use of any opportunity to alter the existing distribution of power in their favour. Pursuit of power, traditionally defined narrowly in military strategic terms, and the promotion of the national interest are the core tenets of realism for survival of the state. Realists are sceptical about the international institutions and oppose the idea of entrusting their security to any external institution (Dunne & Schmidt, 2014).

With an offensive realist perspective, states aim to downgrade the rival countries` power to mitigate the potential threat posed against them. They make a direct connection between power and security by arguing that in order to ensure security, state has to maximize its relative power and achieve superiority in relation to its opponents. In contrast defensive realists believe that states increase their power to ensure balance of power against rival states so that the opponent cannot risk attacking (Slaughter, 2011; Miller, 2010). Consequently, foreign interventions serve both offensive and defensive realist interests by shaping the successor administration and ensuring granted alliance or by counterweighing rival major powers` interests.

As Mearsheimer puts it, realists believe that great powers seek to increase their economic and military power and keep other states under control to prevent them from shifting the balance of power in their favour. Even though Mearsheimer advocate that states are willing to gain as much power as possible and use wars to gain power over a rival state and enhance their security, he also underlines that ideology or economic considerations are crucial along with security as the driving force behind the decision of war (Mearsheimer, 2007).

J.Samuel Barkin also underlines four common aspects of contemporary definitions of realism: the state is the central actor in international politics; states are interested in their own survival to last in an anarchical world; in order to pursue the state’s interests the stateman behaves rationally; states focus more on material capabilities such as military power rather than other forms of power (i.e. economic, organizational, or moral power) (Barkin, 2003). Grieco also states that the anarchical international environment penalizes states when they fail to protect their vital interests (Grieco, 1998).

Realists attribute the selectivity in humanitarian intervention to states` foreign policy agenda aiming to advance national interests through enhancing power that override moral considerations. They also argue that the decision for humanitarian intervention is formed by the cost-benefit analysis and geopolitical interests (Jude, 2012). Bull`s mention of Grotius` distinction between `justifiable` war and `persuasive` war in that context points to the realist conception of using humanitarian intervention as a pretext to pursue their interest (Bull, 2012:43).

Realists in general agree that national interests are the main driver of intervention so interventions take place only when national interests are at stake. However, realist scholars disagree on what defines national interests, whether material or ideational interests. Morgenthau’s classical realism defines interest and power primarily in material and particularly military terms. As an instrument to achieve any interest, power becomes interest (Williams, 2004). Morgenthau describes the intervention as “an instrument of foreign policy as are diplomatic pressure, negotiations and war” and attributes the decision of intervention to national interest at stake and sufficient power available to succeed (Morgenthau, 1967). So in classical realism, pursuit of power is framed as the national interest. The national interest ensures the continuity and consistency in foreign policy (Molloy, 2004).

Some scholars also support the idea that third-party intervention is more likely to be related to interveners’ strategic interests (Regan, 1998; Findley & Teo, 2006; Woodward, 2007). According to the realist point of view, regional or global powers tend to exploit the opportunity and available conditions for foreign intervention to pursue the expansion of influence on civil war states where regional balance of power is at risk and the conflict is detrimental to regional and international peace.

Biased interventions, which aim to alter the likely outcome of the conflict in favour of one side (Carment & Rowlands, 2003) can also be explained by a realist point of view. A potential intervening power will shape its decision for intervention based on its interests and desired end state for the intrastate conflict regarding who will run the country after the conflict. In that context, foreign powers attempt to change the leader or the type of government, economic system of the country, or certain policies of the government (Gent, 2005).

The major powers prefer to grant UNSC authorization before intervention to justify the legitimacy of the intervention; however, UNSC authorization is not an absolute prerequisite for intervention. Specifically when highly strategic interests are at stake and UNSC permanent members have contradicting stances against intervention; major powers may opt to violate or disregard the existing norms with a realist perspective (Allison, 2009). This fact is seen by realists as a reinforcement to their position to explain the motives of the intervention.

In that context realist tradition questions the existence of moral norms that cut across the boundaries of states and regions and humanitarian justifications for intervention(Bellamy, 2003a).

Realists claim that states struggle for power and interests so by and large material interests rather than norms determine the decision for intervention. Under conditions of prevailing international anarchy, states strive for either maximizing power and security or minimizing threats to security for the ultimate aim of survival. From realist point of view, military intervention is an instrument so states intervene only if these interests are at stake (Binder, 2009).

Realists argue that humanitarian intervention is not purely motivated by humanitarian ideals, rather as Morgenthau suggests it aims to maintain or increase the power and contain or reduce the power of other nations’ (Szende, 2012). Realists conceive humanitarian intervention as a means of powerful states using military force to promote their own interests (Bellamy, 2003a).

In sum, realists conceive international relations as a zero-sum game among states competing for power to ensure national survival and secure or promote their national interest in relation to others. In that respect intrastate conflicts are exploited and internationalized by nations to pursue national interests by shaping the post-conflict environment through intervention. In an attempt to explain why states intervene into intrastate conflict, the realist paradigm associates regional and global powers` decisions for intervention/non-intervention into intrastate conflicts and for choosing a side to support with exclusively national and strategic interests at stake.

3. Liberalism and Intervention

The liberalist theory, in contrast to realist view of international politics, opposes the idea of constant conflict and zero-sum game struggle among states, and instead claims that transnational social bonds that link the individual human beings provide a window of opportunity to cooperate. Liberalist theory also supposes that moral imperatives limit the state actions in contrast to the realist conception(Bull, 2012:24-25). Liberalism suggests that interdependency, interaction, and cooperation among states enable and sustain peace and security.

Liberals mainly concentrate on how lasting peace and cooperation in international relations can be ensured. They believe material power is not the sole determinant of international relations and emphasise the role of international institutions in promoting and enforcing peaceful relations among nations by mitigating the implications of existing anarchy. International organizations act as higher authority since the states accept willingly to limit their own power, autonomy, and, to some extent, freedom through a set of rules put in place by international organizations of which they become members (Terriff, Croft, James, & M.Morgan, 1999:46). The empowerment of international organizations ensures the implementation of political, economic, and liberal norms at national and international levels.

Liberals in general agree that states with democracy and free market economy have political environments more conducive to peace. In liberal theory this has been explained by the democratic peace phenomenon which describes the lack of war between liberal states as a result of existing liberal democracies (Slaughter, 2011). Expanding the zone of democratically governed nations in that perspective through intervention and regime change is considered a justifiable action to serve the purpose of establishing more secure and predictable international society.

On the other hand, liberals differ over the role of international institutions and the application of military intervention. Some support the idea that respecting states` sovereignty can be overlooked in case of non-liberal states’ violations of their citizens’ basic human rights (Miller, 2010). Contemporary liberal theory on military intervention identifies two groups of liberal scholars: cosmopolitan interventionists and liberal internationalists. Cosmopolitan interventionists claim that intervention is a moral obligation in case of systematic human rights violations by a tyrannical regime oppressing its own population. Liberal internationalists, on the other hand, justify foreign intervention as a last resort to end protracted civil wars and indiscriminate killing of civilians. They generally insist that military intervention should be multilateral and authorized by the UNSC to be legitimate (Doyle & Recchia, 2011). Many liberals support foreign intervention whenever domestic turmoil threatens international peace and security or the domestic violence results in human rights violations, such as ethnic cleansing and genocide (Hoffmann, 1995).

The basic foundational principle of international relations since 1648 has been the sovereign state. The contemporary consensus requires UNSC authorisation for humanitarian intervention. The definition of humanitarian intervention is “the threat or use of force by a state, group of states, or international organization primarily for the purpose of protecting the nationals of the target state from wide-spread deprivations of internationally recognized human rights” (Goodman, 2006).

However the failures of the UNSC to act in Rwanda and Kosovo, in 1994 and 1999 respectively, had a major impact on normative debate about intervention for humanitarian purposes. In that respect International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS)`s report on “The Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) promoted the idea that sovereign states have the responsibility to protect their own citizens from massacre, ethnic cleansing, genocide, and starvation. If states are unwilling or unable to fulfil their responsibility or the state itself is the one perpetuating these atrocities against their own population then the larger international community should exercise R2P (ICISS, 2001). That normative shift brings about flexibility for military intervention outside the scope of UNSC approval and in practice translates into a `responsibility to intervene` for the international community to end the violence of intrastate conflict (Woodward, 2007). So R2P is perceived as justification for intervention outside of the UN framework in case UNSC permanent members exercise veto power to block resolution for intervention. The idea is to have an alternate tool in case the UNSC fails to act in case of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.

R2P conceives human rights violations as a threat to international peace and security as declared in the UN Charter Chapter VII. Intervention in another state for the purpose of protecting individuals against gross violations of human rights is seen as legitimate and necessary (Bin Talal & Schwarz, 2013). R2P underlines that the state sovereignty cannot be viewed in absolutist terms as an obstacle to international action if states fail to protect their population (Cottey, 2008).

Liberal internationalists claim that new international norms prioritize individual rights and security. So the human security argument provides a framework to achieve international consensus for legitimate intervention (Chandler, 2004). Human security, the aim of humanitarian intervention, recognizes that democratic development, human rights and fundamental freedoms, the rule of law, good governance, sustainable development, and social equity are as important to global peace as are arms control and disarmament (S. Kim, 2003).

Liberalism is committed to the principle that humanitarian need constitutes the only legitimate basis for intervention and asserts that purely self-interested intervention would undermine the basis for the system of international cooperation and cause instability (Szende, 2012).

Past research also shows that humanitarianism influences intervention decisions. When a civil war involves humanitarian disasters, major powers are less likely to care about their own interests, and normative criteria can affect intervention decisions (S. K. Kim, 2012), with a liberalist point of view. The 1991-92 Somalia crisis was believed to pose little threat to US political or economic interests and did not constitute a threat to regional or international stability; however, liberals claims of a dire humanitarian emergency situation in Somalia, with 300,000 Somali dead and almost 4.5 million on the brink of starvation, played an important role in US intervention in Somalia (Western, 2002; Jakobsen, 1996). Military intervention in Kosovo by NATO, conducted without a UNSC approval, has also been acknowledged as a response to massive human rights violations. The ability of international institutions to promote cooperation and manage conflict reinforces the liberalist point of view to promote peace in the world (Robinson, 2010). UNSC’s failure to authorize intervention for Kosovo manifests the dilemma the liberalist face.

Liberal cosmopolitanism, prioritizes the alleviation of human suffering over state sovereignty and support the idea that international society has moral obligation to intervene for humanitarian purposes (Spalding, 2013).

Liberal internationalism`s stance against intervention requires an international order where global institutions rules the world. From the liberal point of view Dunne briefly explains Michael Doyle`s dual-track approach. First liberal community forge alliances with other like-minded states and follow an international policy aiming balance of power to contain authoritarian states. Secondly liberal community maintains an expansionist policy to extend the liberal sphere by economic, diplomatic instruments or through `intervention` (Dunne, 2014). That provides another perspective to comprehend the underlying motives of the foreign interventions.

Liberal international relations theory provides a different perspective with regards to the motivation of state intervention into intrastate conflicts. That perspective opposes the realist assumption that national interests are the main driver of intervention decision. With a liberalist point of view, if an intrastate conflict brings about genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, or humanitarian disaster, global powers should intervene to maintain rule-based international order regardless of the existence of national or strategic interests.

4. English School and Intervention

The English School is seen as a middle way between realist and liberal theories with its key concept of ‘international society’(Brown, 2001). The concept of international society is portrayed as `the via media between an anarchic international system, where politically diverse states compete for power and security, and a world society that gives legal and political expression to a universal moral community of humankind. English School tradition focuses on the shared norms, rules and institutions that maintain the sense of society and order between politically diverse states` (Ralph, 2013).

Bull reinforces English School`s position between the realist and the liberalist tradition. He argues that English School opposes the basic realist argument that states are in constant struggle for interests, and rather advocates that they are bound by the moral values, rules, laws, and institutions of the society formed by mutual interaction (Bull, 2012:25). Bull`s conception of international society has tree substantial basis: a sense of common interests, rules to sustain these goals, and institutions that make these rules effective (Bull, 2012:63).

International society is about the institutionalisation of shared interest and identity amongst states, by shared norms, rules and institutions (Buzan, 2004). According to Hedley Bull`s definition for international society `an international society exists when a group of states, conscious of certain common interests and common values, form a society in the sense that they conceive themselves to be bound by a common set of rules and in their relations with one another, and share in the working of common institutions` (Bull, 2012:13).

Within the English School there is a divide between scholars known as pluralists and solidarists. The divide within the theory is largely in the way the legitimacy of humanitarian intervention is interpreted. Pluralists insist that international society must stick to the established norms and non-intervention to maintain order in the anarchical society while solidarists advocate humanitarian intervention to maintain the international order and rule guided international society (Bull, 2012:16). Jason Ralph explains the source of the tension referring to the controversy between the rule of law, human rights and democracy promotion. While the rule of international law promotes the sovereign equality of states, this concept brings about tolerating undemocratic regimes to abuse their own people (Ralph, 2013).

Whereas pluralist perspective forbids humanitarian intervention on the grounds that it breaches the norm of sovereignty of states within the international society, solidarist view favours humanitarian intervention by international society to collectively enforce the international law in case of violation of shared norms, values, moral considerations (Spalding, 2013).

The pluralists argue that states are enthusiastic to cooperate unless norms of sovereignty and non-intervention are breached. English School supposes that agreed rules and norms mitigate the risk induced by anarchical structure of international society and contribute maintaining international order. States, international organizations, non-governmental organizations are seen as the entities that contribute the formation and management of shared ideas, values, norms and institutions (Jude, 2012).

Pluralists also argue that strong states responding to humanitarian crises selectively, are often motivated more by self-interest than humanitarian concern and humanitarian intervention is illegitimate since it breaches the fundamental norm of sovereignty. On the other hand solidarists claim that international society should not allow human rights abusers to exploit sovereignty while committing crime against their own population. They argue that the protection of human rights has precedence over the norm of sovereignty and non-intervention. They consider humanitarian intervention in case of supreme humanitarian emergency both as a moral responsibility and legal right to act (Bellamy, 2003a)

Widely referred concept of R2P is of concern as much for the English School as it is for liberalists. Its maturity is questioned especially after NATO`s Libya operation. Alex Bellamy examines whether the fact that mandate framed by UNSC Resolution 1973 on Libya is implemented to pursue regime change undermined the chance of R2P applicability to prevent substantial human rights violations and mass atrocities committed during the course of 8 year conflict in Syria. He claims that UNSC’s inability to reach consensus on intervention in Syria crisis stemmed more from considerations regarding the situation in Syria itself rather than from opposition to NATO led intervention in Libya under R2P context (Bellamy, 2014).

Brazil’s objection to implementation of R2P within the framework of UNSC mandate for Libya as a tool to pursue regime change led to Brazil proposal defined as “responsibility while protecting” (RwP). RwP proposes a set of criteria for legitimate military intervention, a monitoring mechanism to assess and control the implementation of UNSC mandates. RwP indeed is an initiative to curb any attempt to exploit R2P by prioritizing national agendas over the protection of civilians (Welsh, Quinton-Brown, & MacDiarmid, 2013). In that context RwP should be considered as the footsteps of a new norm or transformed form of R2P to prevent and respond to mass atrocities.

English School`s main concern as an international relations theory is the relationship between order, justice and norm construction within international society. The central debate revolves around whether reciprocal recognition of state sovereignty and the norm of non-intervention are non-negotiable or protecting basic human rights in case of `supreme humanitarian emergency` thorough intervention takes precedence as a responsibility for international society. Pluralists claim that international society is based on mutual recognition that allows states to pursue their diverse identity and interests within the framework of functional and procedural institutions (Bellamy, 2003b). Pluralists conceive humanitarian intervention as illegitimate action that hampers the basis of international society by breaching sovereignty right and non-intervention norm.

Dunne emphasises Hedley Bull`s broader conception of international society that includes interaction among multiple actors. The international society is seen as the result of the interaction among NGOs, transnational and subnational groups, individuals, institutions and wider community of human kind along with states in historical perspective (Dunne, 2007). For English school scholars, diplomats and leaders are also considered as real agents in international society. Therefore understanding of how diplomats and leaders view the world thorough examining the language they use and the justification they employ for their decisions is a main area of study in English school (Dunne, 2007).

The main trust of the English School has been to understand the nature and the function of international societies, and to trace their history and development (Buzan, 2004). So English School focuses on defining characteristics which forms the boundaries of different historical and normative orders (Dunne, 2007).

English School perspective, as a via media between realism and liberalism, considers international society, formed on the basis of common identity, moral values and interests has the responsibility to intervene intrastate conflicts to uphold human rights, international law and collective international norms.

5. Conclusion

Each IR theory works as a lens to see, understand and make sense of cases in the real world with certain strength, weaknesses and explanatory power.

While realism conceives power, influence, and national/strategic interests as the main drivers of any third-party intervention decisions, liberalism advocates global powers intervene regardless of the existence of national or strategic interests if genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, or humanitarian disaster takes place. As a via media between realism and liberalism, English School reinforce the notion of international society which has the responsibility to intervene intrastate conflicts to uphold human rights, international law and collective international norms. From English School perspective the main drivers of intervention by International Society are shared common identity based on universal moral values and sense of common interests.

*Cem Boke (PhD ) is a non-resident fellow at Beyond the Horizon ISSG.

Bibliography

Allison, R. (2009). The Russian case for military intervention in Georgia: international law, norms and political calculation. European Security, 18(2), 173–200.

Barkin, J. S. (2003). Realist Constructivism. International Studies Review, 5(3), 325–342.

Bellamy, A. J. (2003a). Humanitarian Intervention and the Three Traditions. Global Society, 17(1), 3–20.

Bellamy, A. J. (2003b). Humanitarian Responsibilities and Interventionist Claims in International Society. Review of International Studies, 29(3), 321–340.

Bellamy, A. J. (2014). From Tripoli to Damascus? Lesson learning and the implementation of the Responsibility to Protect. International Politics, 51(1), 23–44.

Bin Talal, E. H., & Schwarz, R. (2013). The Responsibility to Protect and the Arab World: An Emerging International Norm? Contemporary Security Policy, 34(1), 1–15. http://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2013.771026

Binder, M. (2009). Humanitarian Crises and the International Politics of Selectivity. Human Rights Review, 10(3), 327–348. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-009-0121-7

Boke, C. (2017). US Foreign Policy and The Crises in Libya and Syria: A Neoclassical Realist Explanation of American Intervention. University of Birmingham. Retrieved from http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/7995/

Brown, C. (2001). World society and the English School : An “international society” perspective on world society. European Journal of International Relations, 7(4), 423–441.

Bull, H. (2012). The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (4th ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Buzan, B. (2004). From International to World Society? English School Theory and the Social Structure of Globalisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carment, D., & Rowlands, D. (2003). Twisting One Arm: The Effects of Biased Interveners. International Peacekeeping, 10(3), 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1080/13533310308559333

Chandler, D. (2004). The Responsibility to Protect? Imposing the “Liberal Peace.” International Peacekeeping, 11(1), 59–81.

Cottey, A. (2008). Beyond Humanitarian Intervention: The New Politics of Peacekeeping and Intervention. Contemporary Politics, 14(4), 429–446.

Doyle, M., & Recchia, S. (2011). Liberalism in Interntional Relations. In International Encyclopedia of Political Science (pp. 1434–1439). Los Angeles: Sage.

Dunne, T. (2007). The English School. In T. Dunne, M. Kurki, & S. Smith (Eds.), International Relations Theories Dicipline and Diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunne, T. (2014). Liberalism. In J. Baylis, S. Smith, & P. Owens (Eds.), Globalization of World Politics (Sixth Edit). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunne, T., & Schmidt, B. C. (2014). Realism. In J. Baylis, S. Smith, & P. Owens (Eds.), The Globslization of World Politics (Sixth Edit). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gent, S. E. (2005). The Strategic Dynamics of Military Intervention. University of Rochester.

Goodman, R. (2006). Humanitarian Intervention and The Pretexts for War. The American Journal of International Law, 100(107).

Grieco, J. M. (1998). Anarchy and the Limits of Cooperation: A Realist Critique of the Newest Liberal Institutionalism. International Organization, 42(3), 485–507.

Hoffmann, S. (1995). The Crisis of Liberal Internationalism. Foreign Policy, 98, 159–177.

ICISS. (2001). `The Responsibility to Protect`, Report of International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, December 2001.

Jakobsen, P. V. (1996). National Interest, Humanitarianism or CNN : What Triggers UN Peace Enforcement after the Cold War? Journal of Peace Research, 33(2), 205–215.

Jude, S. (2012). Saving Strangers in Libya : Traditional and Alternative Discourses on Humanitarian Intervention.

Kendra, D., & Siri Aas, R. (2018). Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946–2017. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Dupuy%2C Rustad- Trends in Armed Conflict%2C 1946–2017%2C Conflict Trends 5-2018.pdf

Kim, S. (2003). The End of Humanitarian Intervention? Orbis, 47(4), 721–736.

Kim, S. K. (2012). Third-Party Intervention in Civil Wars: Motivation, War Outcomes, and Post-War Development. The University of Iowa.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2007). Structural Realism. In T. Dunne, M. Kurki, & S. Smith (Eds.), International Relations Theories Dicipline and Diversity (First Edit). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, B. (2010). Contrasting Explanations for Peace: Realism vs. Liberalism in Europe and the Middle East. Contemporary Security Policy, 31(1), 134–164. http://doi.org/10.1080/13523261003640967

Molloy, S. (2004). Truth, Power, Theory: Hans Morgenthau’s Formulation of Realism. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 15(1), 1–34. http://doi.org/10.1080/09592290490438042

Morgenthau, H. J. (1967). To Intervene or Not to Intervene. Foreıign Affairs, April, 92–103.

Morgenthau, H. J. (1985). A Realist Theory of International Politics. In Politics Among Nations The Struggle for Power and Peace.

Ralph, J. (2013). The liberal state in international society: Interpreting recent British foreign policy. International Relations, 28(1), 3–24. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047117813486822

Regan, P. M. (1998). Choosing to Intervene: Outside Interventions in Internal Conflicts. The Journal of Politics, 60(3), 754–779.

Robinson, F. (2010). After Liberalism in World Politics? Towards an International Political Theory of Care. Ethics and Social Welfare, 4(2), 130–144.

Slaughter, A. (2011). International Relations , Principal Theories. In Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law.

Spalding, L. J. (2013). A Critical Investigation of the IR Theories that Underpin the Debate on Humanitarian Intervention. International Public Policy Review, 7(2).

Szende, J. (2012). Selective humanitarian intervention: moral reason and collective agents. Journal of Global Ethics, 8(1), 63–76. http://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2011.635679

Terriff, T., Croft, S., James, L., & M.Morgan, P. (1999). Security Studies Today. Choice Reviews Online (Vol. 37). Cambridge: Polity Press.

UCDP. (2018). UCDP, Armed Conflict by Type, 1946-2017. Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). Retrieved from https://www.pcr.uu.se/digitalAssets/667/c_667494-l_1-k_armed-conflict-by-type–1946-2017a.png

Welsh, J., Quinton-Brown, P., & MacDiarmid, V. (2013). Brazil’s “Responsibility While Protecting” Proposal A Canadian Perspective, Canadian Centre for the Responsibility to Protect-CCR2P. Retrieved from http://ccr2p.org/?p=616

Western, J. (2002). Sources of Humanitarian Intervention: Beliefs, Information, and Advocacy in the U.S. Decision on Somalia and Bosnia. International Security, 26(4), 112–142.

Williams, M. C. (2004). Why Ideas Matter in International Relations: Hans Morgenthau, Classical Realism, and the Moral Construction of Power Politics. International Organization, 58(4), 633–665.

Woodward, S. L. (2007). Do the Root Causes of Civil War Matter? On Using Knowledge to Improve Peacebuilding Interventions. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1(2), 143–170. http://doi.org/10.1080/17502970701302789