|

by Joseph Votel[1],Baraa Shiban[2] , R.David Harden[3], Onur Sultan[4] JANUARY 12, 2021 | 5 min read |

Background

On November 16, 2020, a report in the Foreign Policy disclosed the Trump administration was planning to designate Ansarallah, the Iran-backed Houthi militia as foreign terrorist organization as part of its scorched-earth policy against Iran. Reportedly, efforts of UN officials like Griffiths and Guterres, and some other partners like Germany and Sweden did not succeed in dissuading the Trump Administration.

On January 10, 2021, The US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, announced the Department of State would notify Congress of his intent to designate Ansarallah or the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) entity alongside three of its leaders Abdul Malik al-Houthi, Abd al-Khaliq Badr al-Din al-Houthi, and Abdullah Yahya al Hakim.

To answer the concerns that had been made by international bodies, think-tanks and allies, the statement in the US Department of State guaranteed the US Department of Treasury would be ready to provide licenses pursuant to its authorities operating in Yemen and to those of international organizations such as UN, non-governmental organizations as of January 19, the date such designation would be effective from.[6]

This policy brief aims to explore implications of the decision by the Trump Administration in its last 10 days in power and make policy recommendations based on the findings of the authors.

The Precarious Situation in Yemen

Yemen remains the worst humanitarian disaster in the world. The war that has doomed the past of the country has become a lasting phenomenon threatening its future also. According to ACLED data, since 1 January 2015, the war has claimed the lives of at least 133.130 Yemenis.

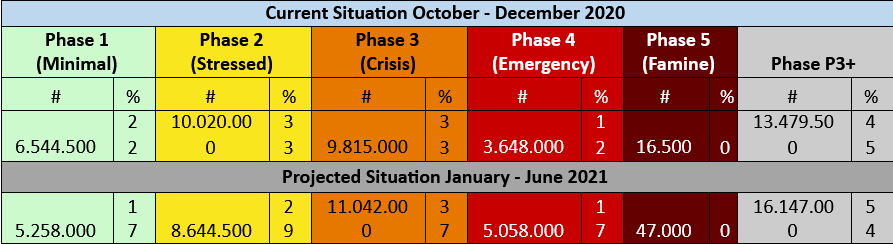

The UN’s Integrated Food Insecurity (IPC) Phase Classification initiative that provides analysis of food insecurity and acute malnutrition situations across the globe illustrated in its latest report that 13.479.500 (45%) of 30.041.712 Yemenis live in IPC Phase 3+ or crisis, emergency and famine conditions. The report further forecasted, with the same rate of deterioration of conditions within the country, the number of Yemenis living in Phase 3+ conditions would go up to 16.147.00 (54%) within the next 6 months. Accordingly, the number of people suffering from famine conditions (Phase 5) could reach up to 47.000. This practically means return of famine that had been averted 2 years ago when action had been taken on five priority issues: protecting civilians, access for humanitarian workers, funding, the economy and progress toward peace.

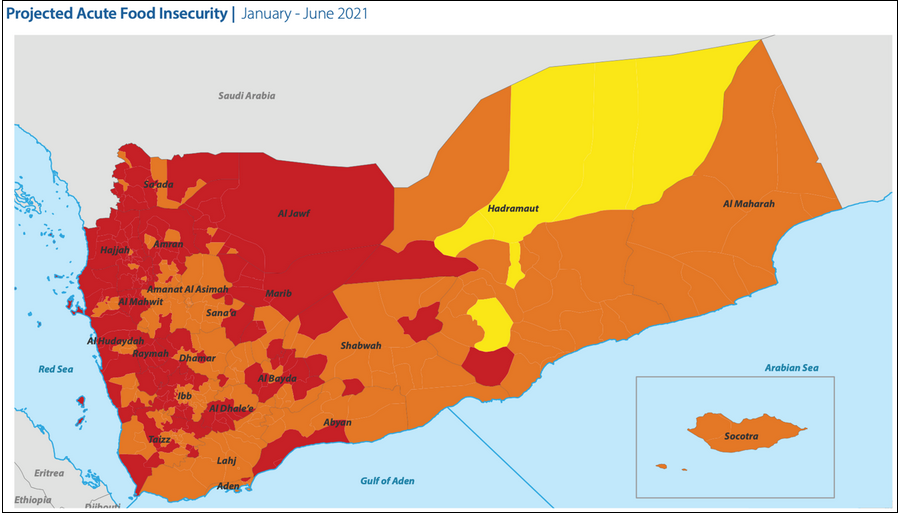

As can be seen in Figure1 below, the majority of those in IPC 3+ levels live in the areas controlled by Houthis.

Figure 1. Food Insecurity in Yemen with Figures[6]

Since the beginning of 2020, the UN Agencies and international institutions have been sounding the alarm bells for Yemen based on two main reasons. The first is Houthi interference into international humanitarian operations in the form of diversion, obstruction and stealing of international aid, and threatening of international aid workers.

The second reason is the budgetary constraints those organizations have. In May 2020, U. N. Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator (OCHA) Mark Lowcock said the UN aid organizations had received $ 3.2 billion

in 2019 and in 2020 they needed $ 2.4 billion for their operations. The pledging conference for Yemen on June 2, 2020 fell one billion short of the target. Despite prior warnings from UN officials that 30 of 41 major aid programmes in the war-torn country would close in the next few weeks without additional funding and that the WFP had halved rations in northern areas since April for the same reason, the plight in Yemen did not generate the required funds.

There are also problems regarding honoring of pledges. Lowcock, attributes reasons for averting famine two years ago to swift honoring of pledges. Accordingly, in 2018, the donors swiftly met 90% of the U.N.’s funding requirements which enabled increase of monthly aid from 8 million to 12 million people. Fast forward to September 2020, the U.N. appeal received only 30% of the pledges totaling to some $1 billion.

In the current conditions, an incoming famine is estimated soon to hit Yemen. On 11 November, UN World Food Programme (WFP) Executive Director David Beasley warned about this saying the WFP had cut aid to 9 million Yemenis from each month to every other month since April 2020, and that it would cut rations additionally for 6 million in January [2021]. If no additional resources were found the WFP would completely run out in March. Such is the capacity and conditions UN bodies have to deal with to reach Yemenis in need with aid.

Another factor that works against Yemeni lives is the inflation or the volatility of the Yemeni Riyal. In the country where 80 to 90% of the staple food, medicines and fuel are imported, any depreciation directly translates into inflation and lower purchasing power. To depict the magnanimity of the depreciations; the YER/USD ratio was around 215 YER/USD before war. It increased to range of 250-290 between 2015-2017. Due to mainly depletion of foreign reserves, Central Bank of Yemen decided to float the YER in August 2017 that caused 40% value loss. Its value decreased to 590 YER/USD in March and 600 YER/USD in August 2019. At the end of 2020, the Yemeni Riyal saw another collapse and the exchange rate reached the level of 880 YER/USD.[7]

So, within 6+ years in war, YER lost its value by more than 300%, severely decreasing purchasing power of the Yemeni households.

The Houthis

The Houthis – a network of small militias with a strict hierarchy – today rule Yemen’s capital Sanaa and several of the country’s northern provinces.

To govern the territory they control, the Houthis run a network parallel to the official state structure that encompasses all sectors of government. The system has many parallels with a gang cartel running a city.

At the top is the “kingpin” Abdulmalik Al-Houthi, surrounded by his trustees. Based on reports from his trustees, the kingpin sets the agenda on a day-to-day basis and is the ultimate authority. Under this close circle are the general supervisors, who do not interact with the public and are usually anonymous. Like the “lieutenants” of a gang cartel, they often have aliases.

On the ground, a network of supervisors who interact with the public and control turf report to these general supervisors. Each supervisor has his own turf that he protects from others, and armed groups run by different supervisors might even clash with each other. These supervisors are a collection of religious fanatics, former criminals, and opportunists. In exchange for authority over their turf, the Houthi leadership expects them to fulfil three main tasks. First, to pass a percentage of any revenue collected up the chain. Second, to recruit for the organization. Third, to run an active indoctrination campaign.

On a daily basis, these Houthi supervisors harass women over their clothing, shut down restaurants and cafes that do not segregate between genders, and enforce a ban on music in weddings and ceremonies – even universities are not allowed to have graduation parties.

They survive through extorting money out of stores and businesses and running oil black markets. Their money-making schemes have attracted criminals and opportunists, who joined the group to profit from the system. People who do not adhere to their moral code can be arbitrarily detained, forcefully disappeared, or tortured to death, without any interference from the judiciary.

Also on the ground is the Houthis’ network of “watchers” – informants who serve as the eyes and ears of the organization. These informants provide information to Houthi officials at various levels, including in some cases directly to al-Houthi’s inner circle.

They also play a censorship role, reporting on individuals and entities who criticize the organization or its leader, including posts on social media, articles and any kind of activity. As a result, journalists are imprisoned, newspapers confiscated, and TV stations closed. People living under the Houthis therefore live in an environment of fear.

The Houthi network is extremely violent and oppressive. In 2015, Reporters Without Borders ranked the group as second only to ISIS in violations against journalists. Human Rights Watch has documented the Houthis policy of hostage-taking, their killing of immigrants, and their constant use of landmines and blocking of aid including during the COVID-19 pandemic. When the conflict erupted in Yemen, the Houthis used dissidents as human shields, holding them in weapon depots being bombed by Arab Coalition forces.

The Houthis have not just established violent, cartel-like control over parts of Yemen, but also promote their sectarian and intolerant ideology. Anyone who criticizes the system is quickly denounced as a traitor, mercenary, or American or Israeli spy. This is in line with the Houthis’ ideology, which doesn’t see them as fighting a tribal war in Yemen but instead waging a struggle against the imperialist states of Israel and the US. Under this worldview, the Houthis’ domestic opponents are portrayed as stooges. Likewise, the Houthis portray Saudi Arabia as an agent of the US and Israel.

The Houthis have disseminated this ideology in the territory they control, including through schools, making significant changes to the education curriculum. They run summer camps to teach their doctrine and run courses that are mandatory to all public employees and school children. In schools, universities, and other institutions, people must pledge allegiance to Abdulmalik Al-Houthi instead of pledging allegiance to the constitution and the Republic of Yemen. Last month a video went viral on social media depicting members of the police academy pledging allegiance to Abdulmalik Al-Houthi and chanting the infamous Houthis chant “Allah is great, death to America, death to Israel, damn the Jews, victory for Islam,” all while performing a Nazi salute.

The Houthis promote a sectarian and hostile ideology. The organization started persecuting Jews, Baha’is and other minorities the moment they came to power. They soon drove millions of Yemenis out of their homes. The Houthis also started a policy of demolishing their opponents’ properties. Their TV channel Al-Masirah epitomizes this hostile propaganda and is not dissimilar from al-Qaeda’s public messaging.

The supervisors recruit children from their schools to serve on the frontlines and prey on the vulnerability and poverty of their families. They use money extorted from the public to keep their recruitment efforts alive. And because there is only a limited amount of money they can extort and tax, this year they started confiscating private businesses and banks.

Humanitarian agencies have also suffered from extortion and the diversion of aid. International non-governmental organizations working in Yemen today cannot run a workshop or carry out a trip to the field without obtaining security clearance from the top Houthi intelligence services. The World Food Programme in December 2019 and April 2020 publicly highlighted the theft and diversion of aid after they exhausted all channels of communication with the Houthis leadership. In early 2020, the Associated Press issued a damning report detailing the corruption, theft and blackmail exercised against UN agencies. The UN has no option but to comply with the Houthis, or risk their programs being shut down.

Motivations Behind the Move and Repercussions

Earlier this month, Morocco normalized ties with Israel. In exchange, the United States agreed to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. This announcement continues the trend of an Arab-Israeli rapprochement outside of a final status settlement with the Palestinians.

This agreement, along with the earlier “Abraham Accords” normalizing Israel’s relations with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Sudan, are positives in a region too often known for war. Fortunately, more peace deals are likely as the Middle East emerges from the post-World War II era.

In its effort to promote regional peace and build an Israeli-Sunni alliance against Iran, the U.S. is rushing to offer Saudi Arabia a gift in exchange for a normalization deal with Israel. With this designation, the administration seeks to sanction the Houthis, weaken Iran, strengthen Saudi Arabia, and bolster the exiled Yemeni government.

Motivations Behind the Move and Repercussions

The Houthis control Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, along with the main ports and crucial infrastructure necessary for the survival for most of Yemen’s civilian population. This FTO designation would prohibit material support — including all trade of food, medicine, sanitation supplies, humanitarian aid, and other basic commodities — in the Houthis-controlled areas, during a global pandemic. Yemen is already experiencing pockets of famine; the Yemeni currency, the riyal, would continue to devalue, and household purchasing power would crater.

There are other unanticipated risks. For example, the United Nation would have challenges in mitigating a potential massive oil spill off the Red Sea from the dilapidated FSO Safer oil tanker — a spill potentially four times greater than was the Exxon Valdez — if it cannot negotiate with the Houthis. This spill would close the main port of Hudaydah, thus further disrupting food supplies. Yemen is already the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, and an FTO designation could very well lead to widespread famine as mentioned before.

The Trump administration has pushed Saudi Arabia to normalize diplomatic relations with Israel before Trump departs the White House and is offering the FTO designation, which — for Saudi Arabia — could blunt Houthi domination of northern Yemen. But Saudi Arabia and Israel would be better served by negotiating peace for peace under the incoming Biden administration, rather than plunging Yemen into an uncontrolled humanitarian collapse. This Faustian bargain fails on many levels.

First, Saudi Arabia will need to reboot its relationship with the Biden administration. In the run-up to November’s election, President-elect Biden has been clear that the tragedy of Yemen must end. There also is a congressional consensus that Saudia Arabia bears substantial culpability for Yemen’s continued war, and a bipartisan recognition that an FTO designation would further destabilize the country.

Instead of helping to resolve the civil war in Yemen, the Saudi kingdom would deepen the crisis with this FTO designation. It would have millions of starving Yemenis on its long, porous border — and an empowered Houthi insurgency that likely would increase its use of Iranian weaponry to quicken the pace and sophistication of attacks against Saudi infrastructure, cities and ports. Just as Hezbollah and Hamas became stronger after their 1997 FTO designation, the Houthis would seek a similar growth in military power and regional influence.

With regard to Israel, its growing realignment with the Sunni states is irreversible. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, however, will need to course-correct with the incoming Biden administration — and the U.S. president-elect surely has not forgotten Netanyahu trying to embarrass him on his 2010 trip to Israel by announcing further settlement construction in the West Bank. The Israeli prime minister also sought to humiliate then- President Obama and Vice President Biden by delivering a 2015 speech in opposition to the Iranian deal to a joint session of Congress, as a foreign dignitary without a White House invitation. Netanyahu should start by recognizing that the risky incentives the Trump administration is offering to Saudi Arabia are antithetical to long-term U.S. and Israeli strategic interests.

Third, Iran will use a Houthi FTO designation to its advantage, which is particularly counterproductive given that the Biden administration will soon renegotiate to curb Iran’s march to the nuclear bomb. Iran’s goal is to shape the region through a “Shia Crescent” of power from Beirut through Damascus, Baghdad and to Sana’a, buttressed by home-grown nuclear capabilities. A deeper Houthi alliance in Yemen allows Iran to project destabilizing threats to Saudi Arabia along its southern flank. With Iran negotiating from greater regional strength, the United States will find it harder to curtail the clerics more-pressing nuclear ambitions.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Attempting quick and straightforward solutions to problems with deep underlying tensions too often leads to strategic disappointment, and Yemen has repeatedly proven this to be true. Now is the time for a political reset — and the United States, not a direct combatant in the civil war, but certainly an important and influential leader in the region, must play an important role.

This role must include encouraging all sides toward a more inclusive political process that reduces violence and raises Yemeni and international voices, and moves toward specific and achievable objectives over time. Solutions that purport to be either speedy or simple are, in fact, quite dangerous. To that point, the current administration’s consideration of designating Ansar Allah (the Houthi movement) as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) will not help advance the United States or the other various participants in this conflict toward a durable strategic settlement.

The Houthi movement has provoked and prolonged the conflict in Yemen and now presides over a starving population and a country whose infrastructure is quickly disappearing. They deserve no one’s sympathy. But designating them as a terrorist organization at this time would not serve global interests or hasten the end of the conflict. Instead, it would complicate the political process and resolution of the humanitarian disaster. It would also undermine the credible and effective counter-terrorism programs that the US relies upon to keep terrorists at bay.

With most of the Yemeni population living in areas under the Houthi movement’s control, designation as an FTO will disrupt the delivery of critical humanitarian assistance for millions of people. FTO designation will slow or stop international agencies that pay aid workers to provide Yemenis essential services. And the designation will further complicate the efforts of the U.N. special envoy to advance negotiations and move forward with what everyone knows will be a lengthy process to normalize and rebuild Yemen.

FTO designation is a useful tool in counter-terrorism kit-bag. It is most effective when focused on specific individuals or groups and then linked to other counter campaigns. It focuses resources, brings to bear many other non-military means that limit freedom of action, and cuts off external support for those designated. It has, however, second- and third-order effects that can work against longer-term objectives and interests, including those particulars discussed above. The big idea is to advance interests, not make the situation worse. We should be mindful of these effects as we consider our options in Yemen.

Yemen’s current situation begs for a broadly supported and dynamic political process, and our actions going forward must be aimed principally at this purpose. FTO designation will not help and will likely make a bad situation even worse.

NOTES:

* This policy brief has been a synthesis of four separate articles of the authors, namely; “Political support, not terrorist designation, is key to moving forward in Yemen” by Joseph Votel, “Why Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthi movement should be designated as a terrorist group” by Baraa Shiban, “Devil’s bargain: Sacrificing Yemen for a Saudi-Israeli peace deal” by R.David Harden, and “What Change Should We Expect in Yemen after Election of Biden” by Onur Sultan, and panel discussion held on January 12, 2021.

[1] Joseph Votel is distinguished senior fellow on national security at Middle East Institute. He retired as a four-star general in the United States Army after a nearly 40-year career, during which he held a variety of commands in positions of leadership, including most recently as commander of U.S. Central Command.

[2] Baraa Shiban is a Yemeni activist and a researcher for the human rights organisation Reprieve. He previously served as the organisation’s Project Coordinator in Yemen. Shiban was the youth representative at Yemen’s National Dialogue in 2014 and has served as an advisor to the Yemeni Embassy in London for more than four years.

[3] R.David Harden is the managing director of the Georgetown Strategy Group. He is former assistant administrator at USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance, where he oversaw U.S. assistance to all global crises. He managed USAID’s Yemen response in the beginning of the Trump administration, based in Jeddah.

[4] Onur Sultan is a senior research fellow and Director of Terrorism, Conflict and War Department in Beyond the Horizon ISSG.

[5] The statement read: “The United States recognizes concerns that these designations will have an impact on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. We are planning to put in place measures to reduce their impact on certain humanitarian activity and imports into Yemen. We have expressed our readiness to work with relevant officials at the United Nations, with international and non-governmental organizations, and other international donors to address these implications. As part of this effort, simultaneously with the implementation of these designations on January 19, 2021 the U.S. Department of the Treasury is prepared to provide licenses pursuant to its authorities and corresponding guidance that relate to the official activities of the United States government in Yemen, including assistance programming that continues to be the largest of any donor and the official activities of certain international organizations such as the United Nations. The licenses and guidance will also apply to certain humanitarian activities conducted by non-governmental organizations in Yemen and to certain transactions and activities related to exports to Yemen of critical commodities like food and medicine. We are working to ensure that essential lifelines and engagements that support a political track and return to dialogue continue to the maximum extent possible.”

[6] “Yemen: Acute Food Insecurity Situation October – December 2020 and Projection for January – June 2021,” IPC, December 12, 2020, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipcinfo-website/resources/resources-details/en/c/1152951/.

[7]ACAPS identifies three major reasons for the depreciation of the YER:

- announcements from either CBY of new regulations on imports and money exchangers,

- import restrictions due to closure of ports,

- depletion of USD available in the formal and informal market.