Introduction

When a large amount of ammonium nitrate exploded in the port of Beirut in August 2020, it left a swath of destruction in the city. The incident caused, among others, 218 deaths, thousands of injured, and millions of dollars in property damage. Consequently, the attention of the world shifted to Lebanon’s capital for a brief time, only to disclose a glimpse of the havoc that dominated the country. A mix of overlying economic, banking, and political crises has brought Lebanon to the brink of failure, a tense situation that deteriorates with each passing day.

Fuelled by economic grievances, the people took to the streets to express their discontent with the country’s sectarian elites. Yet precisely, these elites appear incapable of overcoming the crisis. Najib Mikati was appointed prime minister for the third time in June and currently runs a caretaker government tasked with damage control. Meanwhile, the country’s president, Michel Aoun, has left office without an executive successor.

In exactly this situation of chaos and uncertainty, the seemingly good news was heard from the region. On October 27, 2022, Lebanon and Israel signed a deal that effectively shelves an enduring conflict over the neighbouring countries’ maritime border and the respective resource fields in the Mediterranean Sea. The deal has the potential to make Lebanon a gas exporter. However, doubts remain whether it can be the solution to the country’s problems.

The Maritime Border Deal: An Economic Deal of Two Countries at War

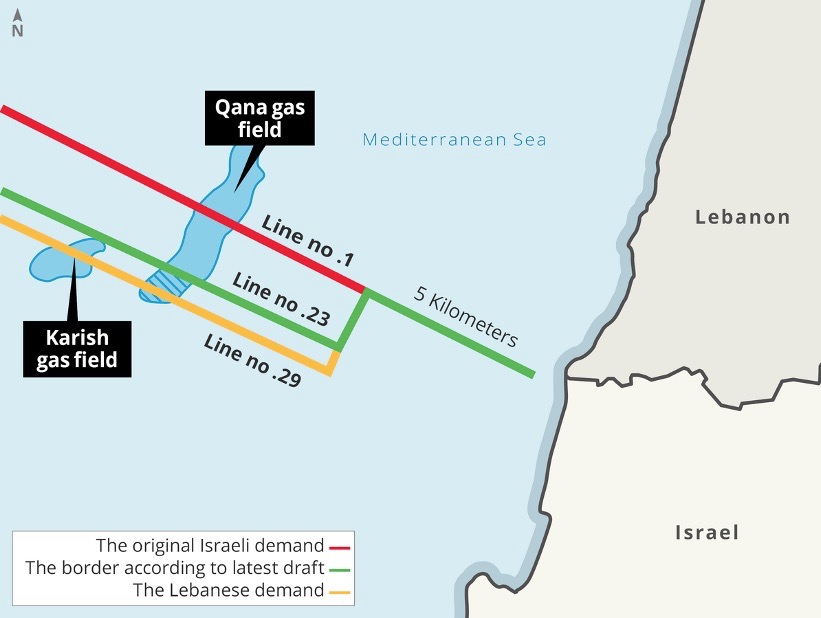

On October 27, 2022, Lebanon and Israel signed their first official agreement after the ceasefire of 2006. This US-brokered deal on the exclusive economic zones and use of undersea gas fields settle a dispute about the maritime border of the two countries that has been raging for several years. The contested area is about 860 square kilometres and houses the two gas fields, namely Qana and Karish, which both countries previously claimed to be their own.

Recent talks on this long-lasting conflict, led by US diplomat Amos Hochstein, were held indirectly since 2020 due to the fact that the two countries do not maintain official diplomatic relations. According to the deal, Israel will get exclusive access to the Karish gas field, while Lebanon will have access to most of the Qana gas field. However, with the Qana gas field being partly located beyond the border to Israel, Lebanon will need to pay royalties to Israel, which amount to 17% of the earnings from the Qana gas field, according to leaked documents.

Figure 1: Several border lines have been proposed throughout the talks, with the agreement having settled on line no. 23. Further, the agreement leaves the so-called “buoy line,” a 5 kilometres demarcation established by Israel single-handedly, untouched (Source: Israel and Lebanon Officially Sign Maritime Border Deal, Haaretz).

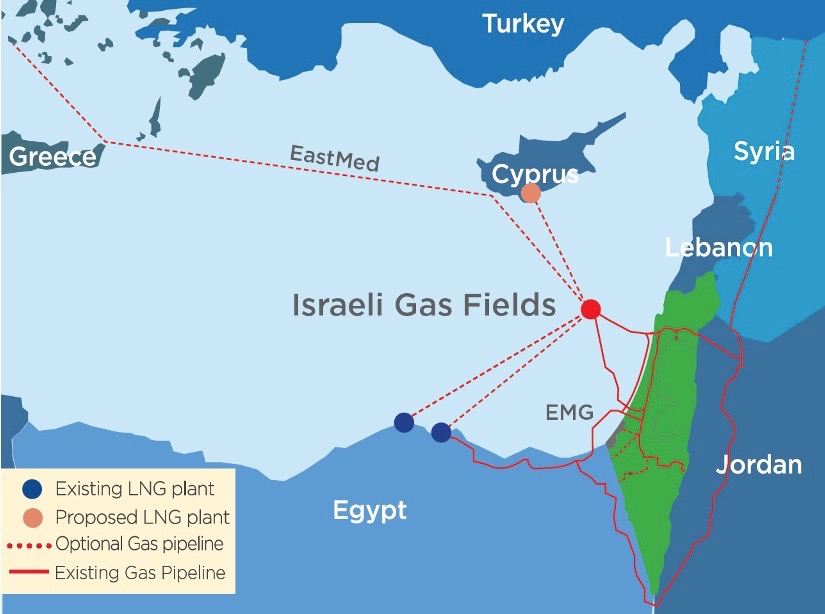

The agreement now appears to satisfy both sides, with Israel scenting an opportunity for valuable gas exports to Europe amid the European gas crises, while Lebanon sees this as an escape route from the economic crisis. Gas exports between Israel and Europe have recently surged by 22%, making the country a meaningful energy partner. In Lebanon, a delegation of the French giant Total Energies arrived right away to discuss a potential course of action.

Although the agreement has been hailed as a milestone achievement, with Joe Biden calling it “a historic breakthrough in the Middle East,” it should not deceive observers about the alleged rapprochement between the two countries. Formally, a peace agreement between Israel and Lebanon has never been reached, and the two countries are under the 1948 armistice agreement. Instead, economic grievances and opportunities pushed the respective governments to reach this agreement. In Lebanon, even Hezbollah, a fierce opponent of Israel, gave in to the deal due to the severe economic crisis.

In both countries, the political circumstances pressured the governments for this decision. While Lebanon’s President Michel Aoun was close to the end of his term, elections loomed on the horizon in Israel.

Downward Spiral: Lebanon in Endless Crisis

Lebanon is in an alarming situation, and several severe crises overlap. Foremost, Lebanon’s economy is suffering, with massive hyperinflation, and the Lebanese pound has lost more than 90% of its value since October 2019. Furthermore, a deficit of foreign currency, which also stems from the Covid-related regression of tourism, aggravates the impact on the Lebanese pound and the Lebanese economy.

The Lebanese economy has not been anywhere close to financially sustainable diversification with its reliance on tourism and foreign remittances from the country’s big diaspora community. Furthermore, events like the Beirut port blast in 2020 or processes such as a brain drain of educated young citizens further wreak havoc on Lebanon’s economy.

In 2020, the government defaulted on its foreign debts and is now in urgent need of a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The deal already fell through once, and current reform demands by the IMF have not been met. A banking crisis with banks being largely insolvent only exacerbates the situation.

For Lebanese citizens, this crisis manifests itself in various forms. As part of the austerity measures, the government has lifted subsidies on fuel, wheat, and medicines, leading to skyrocketing prices and declining purchasing power of the average citizen. Furthermore, unemployment and poverty are on the rise, with the UN classifying four out of five Lebanese as poor. Meanwhile, basic public services have already collapsed. An illustrative example of the latter is the dysfunctional energy sector. While state-owned providers nearly stopped their energy provision, people reverted to expensive diesel generators leading to citizens being unable to use electricity reliably. With the problems having grown so vast, people turn towards their expat friends and relatives for necessities that are impossible to get in Lebanon.

According to the World Bank, the Lebanese economic crisis could be one of the world’s three worst crises in the last 150 years, which illustrates the need for urgent action. The World Bank also states this crisis to be a “deliberate depression” accusing the country’s political elites of having consciously orchestrated it.

This directly hints at a second interwoven crisis of a political nature. Lebanon currently has only a caretaker government run by Najib Mikati, with limited powers and restricted abilities. Furthermore, President Michael Aoun, a Hezbollah ally, left office on October 31, 2022, without a successor being in place. In a final move, Aoun signed a decree finalising the resignation of Mikati’s government to which the serving prime minister, however, reacted deprecatingly. According to the constitution, this act will also not change anything, considering how Mikati’s cabinet is already in the position of a caretaker government.

This is, therefore, the first time that Lebanon neither has a functioning government, nor a head of state. Critics fear that such a situation could aggravate the political deadlock and the economic crisis which would complicate negotiations with the IMF about an urgently needed aid package.

Furthermore, the political system is beset by widespread corruption, fractious political parties, and a lack of consensus. The latter is certainly also due to the country’s sectarian power-sharing political system that distributes political power among the Christians and Muslims at a first level, and then further among the different sects such as Sunnites, Shi’ites, Druze, and Alawites among Muslims, and Maronites, Orthodox, and Catholics among Christians on a second level. Arguably, this inherently unstable political system has fuelled political immobilism, deadlock and economic crisis since its onset.

The Deal and its Consequences: Can it be Lebanon’s salvation?

By settling a maritime border conflict, the agreement partially calms a border conflict between two countries at war that has been smouldering for many years. In the future, economic interest instead of sabre rattling and skirmishes will likely define the countries’ future. Hezbollah’s approval of the deal displays signs of hope for eventual peace between Israel and Lebanon.

Probable economic benefits which the region holds would have been off the table if the conflict between the two countries had put the development of gas infrastructure at risk. In terms of regional security, the deal, therefore, creates incentives dependent on mutual economic interests to stay calm along the common borderline.

For Lebanon specifically, the prospective extraction of natural gas represents a lifeline out of its misery. Current estimates expect Lebanon to be able to generate 100 to 200 million dollars a year from gas production in the Qana gas field; money that could be used to pay off its 100 billion dollars of debt. However, any such predictions are ambiguous.

Although the deal appears beneficial for both parties, it seems that Israel will cash in on it more. While Lebanon has not yet developed a suitable gas infrastructure to generate revenue from its newly gained territory, Israel can start extracting right away. This enables Israel to take advantage of the current energy crisis in which especially European states are willing to pay high prices for the natural resource. Meanwhile, Lebanon is not expected to be able to see any revenues before the end of the decade.

Figure 2: Currently, Israel exports its gas to Europe via LNG plants in Egypt. After having reached certainty with the agreement, Israel can also proceed with its ambitious plans to export to continental Europe directly through a yet-to-build pipeline, making Israel to become a main gas exporting state (Source: Export, Israeli Ministry of Energy).

Furthermore, as previously discussed, Lebanon is in deep trouble. Years of political mismanagement and economic crises have put the country in need of systemic reform efforts to tackle its problems. Building a reliance on gas for the long term might not be the most reliable way forward. Especially with the war in Ukraine and the climate crisis causing governments to speed up the development of renewables, gas could prove unsustainable, economically and climatically in the medium future.

Critics, therefore, point out the mist of uncertainty that accompanies the deal for the Lebanese side. Especially the complexity of turning economically struggling Lebanon into a gas exporting country and the unclarity of the agreement rather suggests that “this deal was ultimately much more profitable for Israel. What Lebanon got was avoiding problems it can’t afford to deal with right now.”

Moreover, with Benjamin Netanyahu having won the Israeli election and having been nominated as the next PM, the deal might be on the line. Indeed, Netanyahu has stated that he is willing to tear the agreement, although US backing of the agreement makes such a move unlikely. Further, it is highly questionable whether Israel under Netanyahu will agree to concessions to Lebanon at all. With radical politicians like Ben Gvir having been nominated for ministerial posts, it is probable that the spirit of cooperation between the two countries could fade again.

In conclusion, the maritime border deal between Israel and Lebanon is fragile and uncertain. Although the deal presents some form of progress and opportunity, it is no silver bullet for Lebanon to evacuate its economically alarming situation. For that, a more comprehensive, and especially a more certain approach, is needed. The border deal might be a good start and, certainly, the best Lebanon can currently get, yet it is not enough.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Ibrahim Jouhari for his comments on the draft version of the article.

Mats Radeck is a research assistant intern at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. He also follows a master’s program in International Relations with a special focus on “Global Conflict in the Modern Era” at Leiden University.