The EU enlargement processes have resulted in the emergence of new patterns and forms of migration within Europe. In this new setting, the natives of member states exposed to financial instability look for better jobs in the West, South, or North Europe. According to the Council of European Union , the EU saw record number of immigrants in 2019 totalling to 17.9 million mobile EU citizens. 50% those came from Romania, Poland, Italy, Portugal, and Bulgaria. 26% of working-age EU-citizen migrants chose Germany as a destination country, 20% UK, and 28% Spain, Italy, or France (Annual report on intra-EU labour mobility, 2020). Data from 2010 (55% men, 45% women, calculations based on Eurostat) shows a higher number of men migrants than women in European countries. However, more recent assessments have shown a shift in gender-based migration patterns. As of 2020, female worker migrants outnumbered males with 51% against 49%, respectively (Publications Office of the European Union, 2021). This article seeks to explain reasons for this shift in mobility patterns within the EU.

According to Eurostat immigration data holding figures for the period between 2010 and 2018, the migration pattern showed dominance of Eastern European males that migrated to a Western country to enter the labour market. They sent remittances to their countries while the women stayed in their home country and cared for the children and the household. Studies on gender stereotypes in Europe show that 69% of people in Romania, 81% in Bulgaria, and 54% in Europe believe “the most important role of a woman is to stay home and take care of the family” (Report on equality between women and men, EU, 2018). This motivated more and more men to leave their home country to earn for their families while the women remained at home.

In cases where men have trouble fulfilling their gender role as economic providers, women are faced with the pressure of finding alternative strategies to support the family. Gender norms have always been deeply inscribed in the definition of these labour market needs. Furthermore, new mentalities on the place of women in society emerged. It is arguable this male dominance has been disrupted as of mid-2020 where the share of women migrants in Europe reached 51.6 %. (UN DESA, 2020).

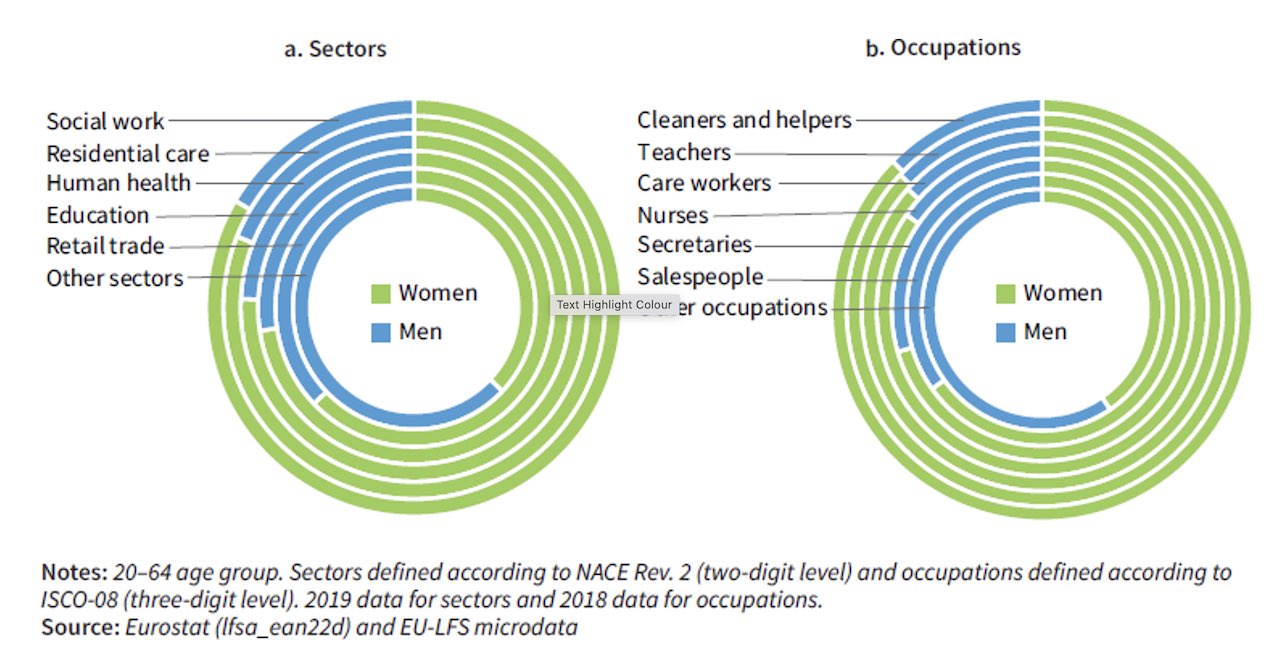

A feminist perspective requires analysing how women and men participate differently in the Intra-European migration phenomena and how expectations for migrants change in society (Silvey, 2004; Parreñas, 2009). First, we can see that the segregation of roles in the family and society in one’s home country is reflected in how migrants integrate into the labour market. Employment sectors are defined by strict gender scripts, coded as either feminine or masculine. Gender segregation is also maintained by bilateral agreements negotiated between States regarding foreign labour recruitment. This standpoint generally upholds the sexual division of labour, recruiting men to work in certain sectors (e.g., construction) and women to work in areas concerned with entertainment, health, cleaning, and the care of children, the elderly, and/or persons with disabilities as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, women migrants in Europe are subject to established gendered directed positions.

Figure 1: The main work activation sectors and occupations of the women migrants in Europe.

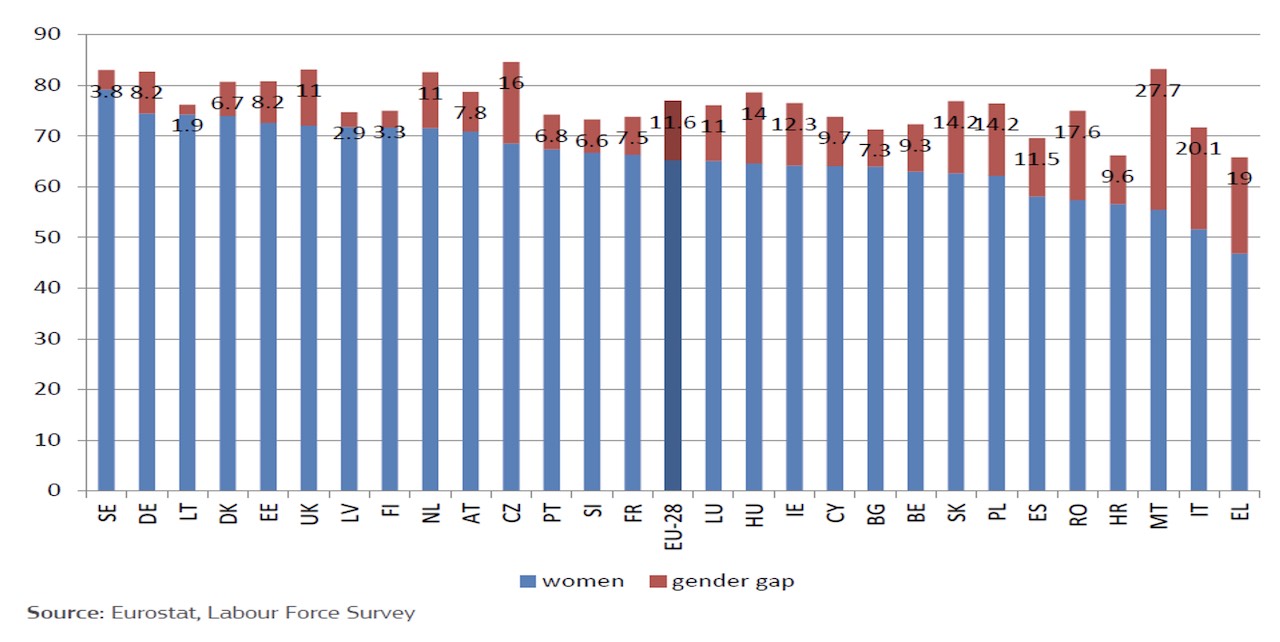

Female migration is also motivated by a gender employment gap. The differences between gender gaps in the EU could have encouraged more women to search for jobs in other countries. These include Italy, Spain, Romania, Hungary, and Czechia, known to have a high gap between men and female labour market acceptance, as shown in Figure 2. A gender employment gap doesn’t only hinder women from participating in the labour market, but it also creates a barrier between men and women due to prejudices and stereotypes. Migrating to another country becomes a way to attain dignity, safety, and fairness.

Figure 2: Women employment rate and gender employment gap, 20-64, per Member State, 2016

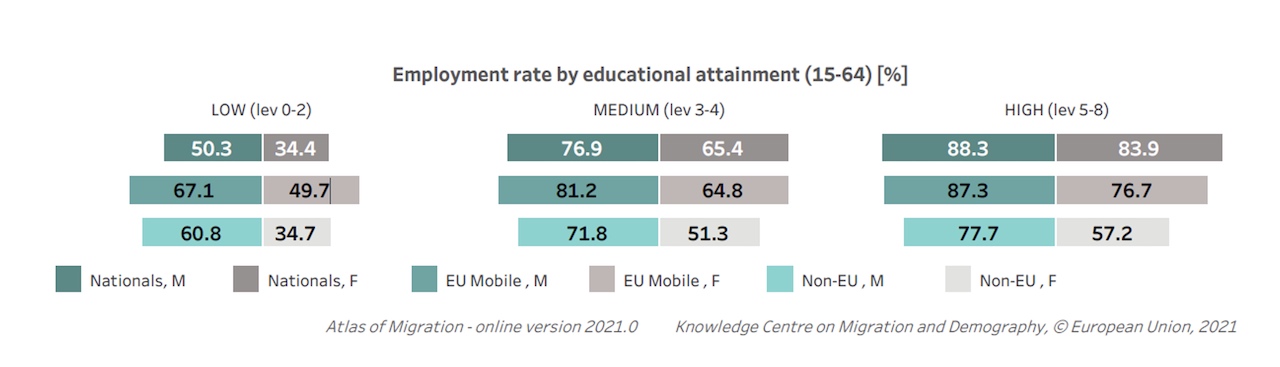

Employment remains to this day a gendered concept which reflects on gender migration. As shown in Figure 3, the employment rate of women migrants from the EU is significantly lower than the employment rate of men despite their level of education. Recent studies also showed a 4 percentage point increase in the share of highly educated migrants between 2011 and 2019; hence, more than a third of migrants are highly educated. The study overall suggests highly educated female EU national migrants’ employment pattern reflects an inverse relationship when compared to that of nationals. The least educated migrants for example by 49,7 percent find employment while this figure is 34,4 percent for nationals. Yet, overall, the more educated the migrant is the higher chances are for finding a job (low educational level by 49.7 %, medium level by 64.8 %, 76.7 %).

Female employees also meet disadvantages at their work place. This occurs especially in Eastern countries where political difficulties prevent the implementation of the right policies regarding gender gap. Despite the European Commission’s strategies to lower pay gaps and promote a gender equality strategy in 2020-2025, many countries took zero action in this direction. One of the six measures outlined in the strategy focuses on integrating a gender perspective in all EU policies and processes. Despite this, countries such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Latvia, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia remain passive about women’s professional prospects due to internal political debates (according to the Eurofund).

Figure 3: Employment rate by education attainment

A factor that renders analysis of the intra-EU migration from a gender perspective, at best, complicated is the status of mobile Europeans. Their right to work in all the European member states impedes receiving countries from recording the flow of migrants. Therefore, little or no data is available on seasonal or mobile workers, and thus the gender ratio is unknown.

All in all, more Europeans, regardless of gender, choose to migrate to other European member states in search of financial stability. For many years, males had the status of primary providers for their homes and they were therefore expected to search for work in other countries. In recent years, a shift between genders in intra-EU migration has reflected attitudes towards the female position in society and the job market. Such discrepancies strongly influence the rise in the number of migrating women from Eastern to Western or Northern European countries. Females become more independent, providers for their families while they are still held back by gendered positions and are motivated to migrate on the premise of gender inequalities experienced in their home countries.

Florentina Drobota is a research and project assistant intern at Beyond the Horizon ISSG.