Executive Summary

- Security Realignments: The second Trump term will likely strain traditional alliances. In Europe, NATO’s cohesion could be undermined by U.S. demands for burden-sharing and hints of disengagement, prompting the EU to bolster its own defense autonomy. In the Indo-Pacific, Washington’s intensified focus on deterring China might continue, but unpredictability in U.S. commitments could unsettle allies like Japan and South Korea, even as regional tensions (Taiwan, Korean Peninsula) sharpen.

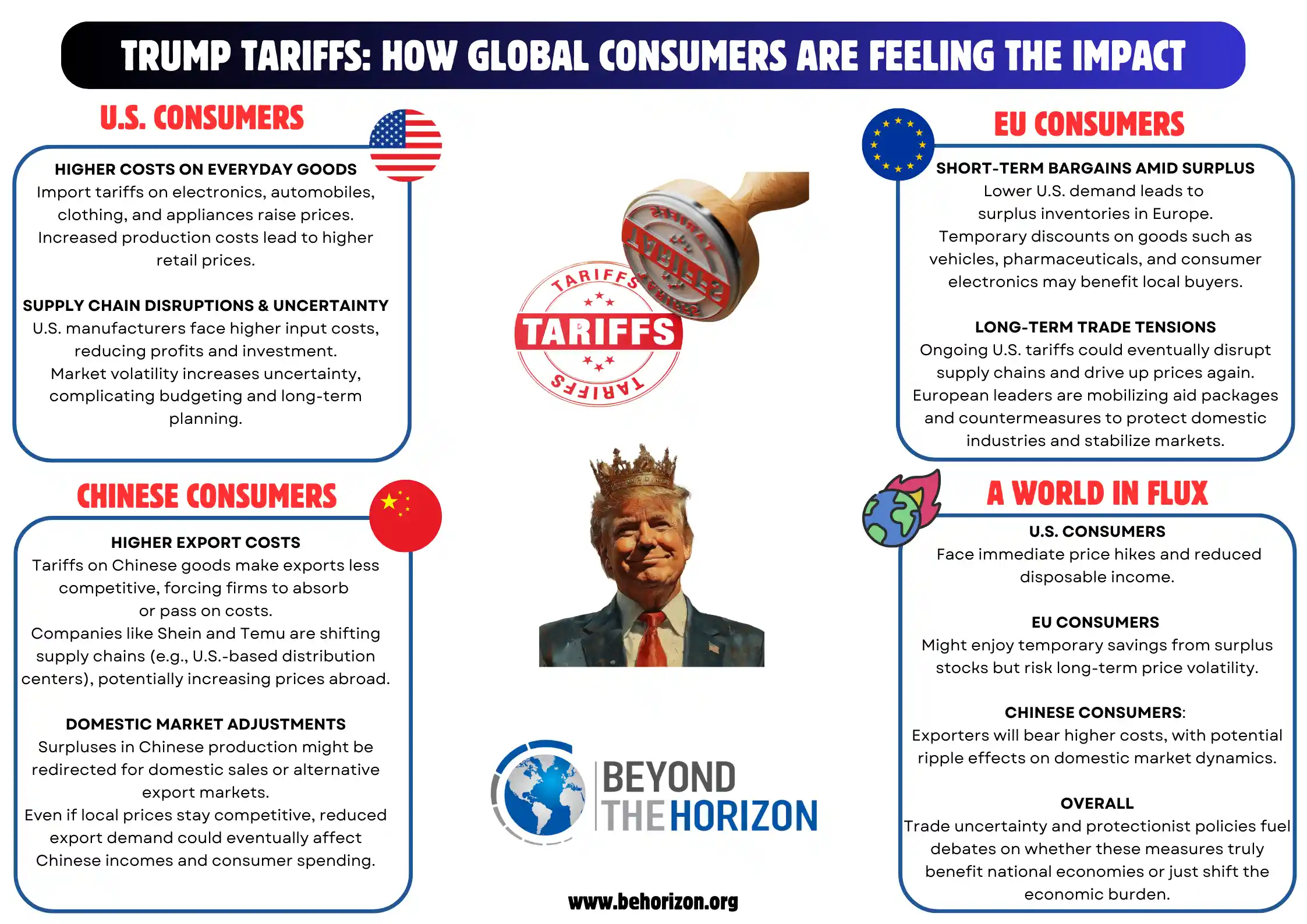

- Economic Disruptions: “America First” trade policies are poised to escalate. Broad U.S. tariffs on imports – from European autos to Chinese goods – would disrupt global supply chains and invite retaliation. Europe and key Asian economies are already responding by seeking closer trade cooperation with each other (e.g. Japan–Korea–China supply chain pacts) to buffer against U.S. protectionism. A fragmented trade landscape with higher costs and trade diversion is expected.

- Technological Decoupling: The Trump administration is expected to double down on decoupling from strategic competitors. Controls on semiconductors and critical tech exports to China would tighten, with parallel efforts to secure critical minerals and AI leadership via new trade deals. This will deepen the bifurcation of tech ecosystems, forcing Europe and Asia-Pacific nations to choose sides or attempt neutrality in standards and supply chains for chips, 5G, and green tech.

- China’s Opportunism: Beijing is poised to exploit rifts and vacuums. Any transatlantic split or reduced U.S. presence in Asia will be met by Chinese outreach – from courting the EU as a “strategic partner” in a multipolar order to bolstering regional trade blocs like RCEP. China will seek to present itself as a stable alternative on trade and climate, even as it quietly advances its own strategic aims in Asia (South China Sea, Taiwan) under the shadow of U.S. distractions.

Introduction

The re-election of Donald Trump for a second presidential term (2025–2029) presents significant implications for the global geopolitical order, particularly affecting the security, economic stability, diplomatic relations, and technological landscape across Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Trump’s distinctively transactional approach to international affairs, combined with his persistent focus on “America First” policies, suggests an era of increased uncertainty and recalibration of traditional alliances and institutions.

Europe, already navigating tensions exacerbated by the ongoing war in Ukraine and the imperative to achieve greater strategic autonomy, will face heightened challenges as NATO cohesion and EU unity come under renewed scrutiny from a more conditional and less predictable U.S. partner. Concurrently, in the Asia-Pacific region, Trump’s hardline stance against China is expected to persist, potentially intensifying regional tensions, reshaping defense commitments, and compelling allies such as Japan, South Korea, and India to recalibrate their strategic postures.

Against this backdrop, China is positioned to leverage the emerging geopolitical landscape, seeking to exploit divisions among traditional Western allies and expanding its strategic influence within Asia and beyond. This policy brief explores these dimensions in detail, beginning with the critical security dynamics and their implications for regional stability and international security architecture.

Security Dynamics

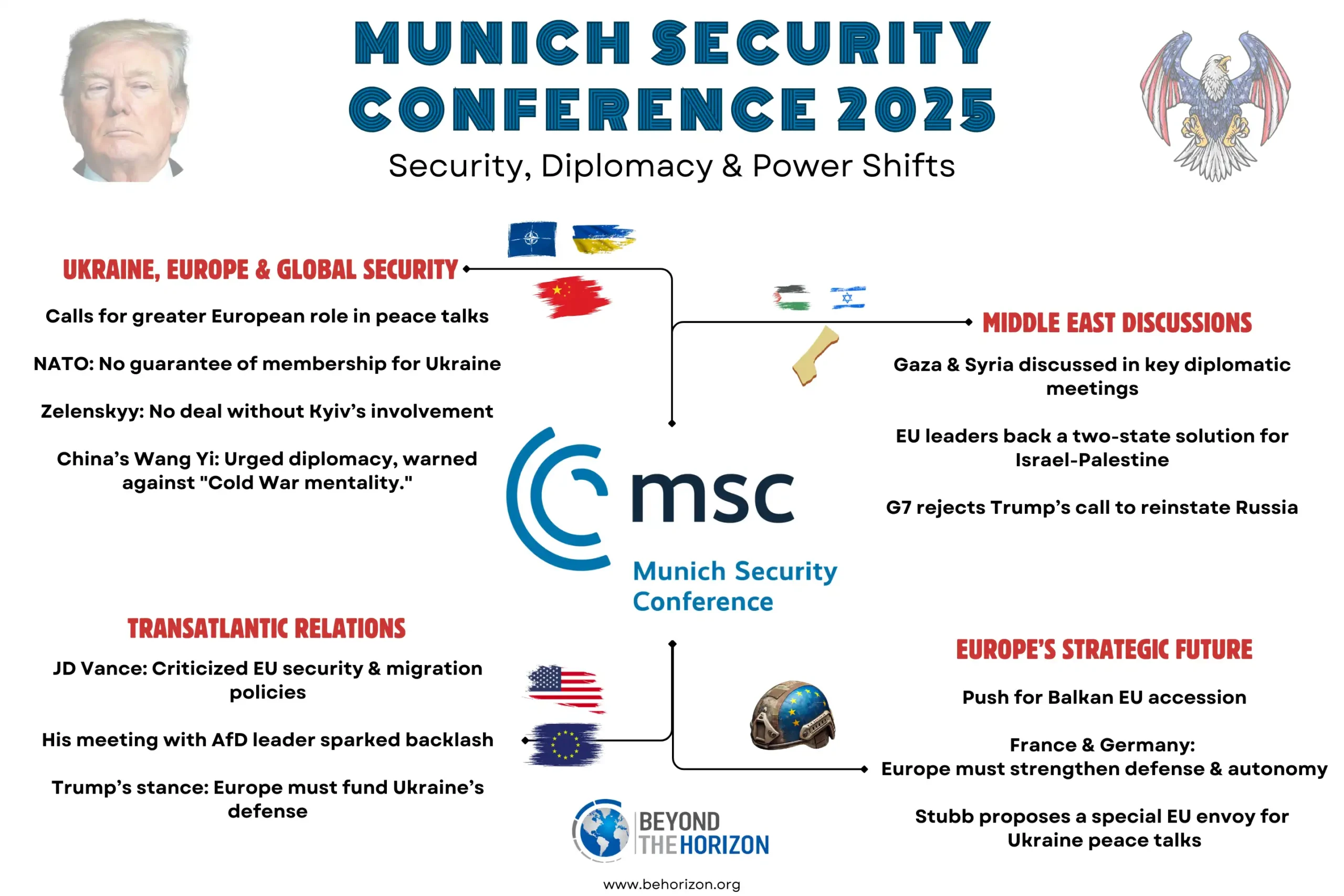

Transatlantic Strains and European Defense

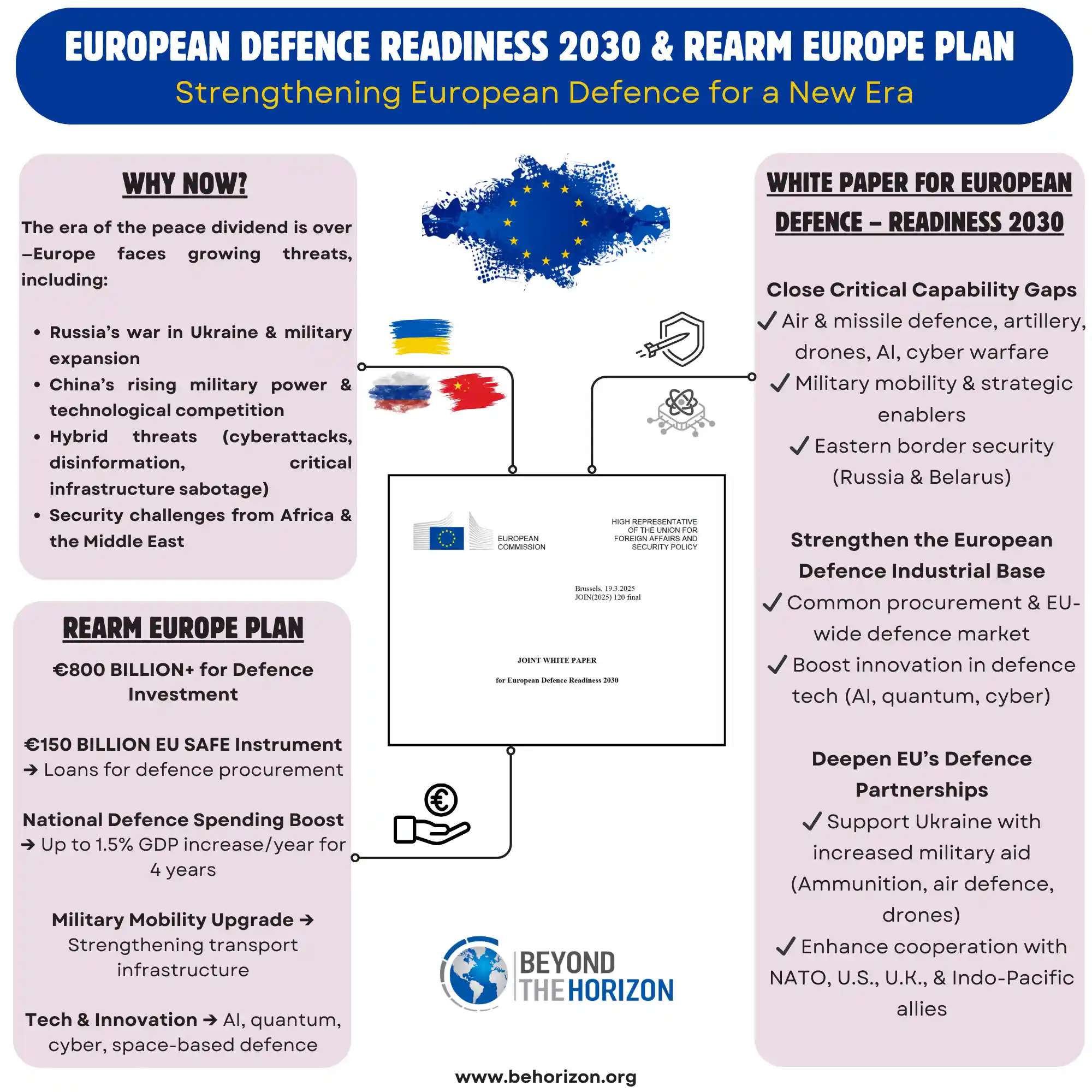

NATO Under Uncertainty: President Trump’s skepticism toward NATO and demands that Europe “pay their fair share” are expected to intensify. During his campaign and first term, Trump openly questioned the U.S. commitment to Article 5 mutual defense and disparaged “delinquent” allies on defense spending. In a second term, such rhetoric could translate into concrete actions: reducing U.S. troop deployments in Europe or even threatening to withdraw from NATO outright. European leaders fear that a drastic U.S. shift on NATO’s security guarantees would have “profound consequences for European security,” potentially emboldening Russia. A recent analysis warns that a U.S. abandonment of Europe would be as destabilizing for the EU “as a nuclear attack,” underscoring the existential anxiety among European strategists.

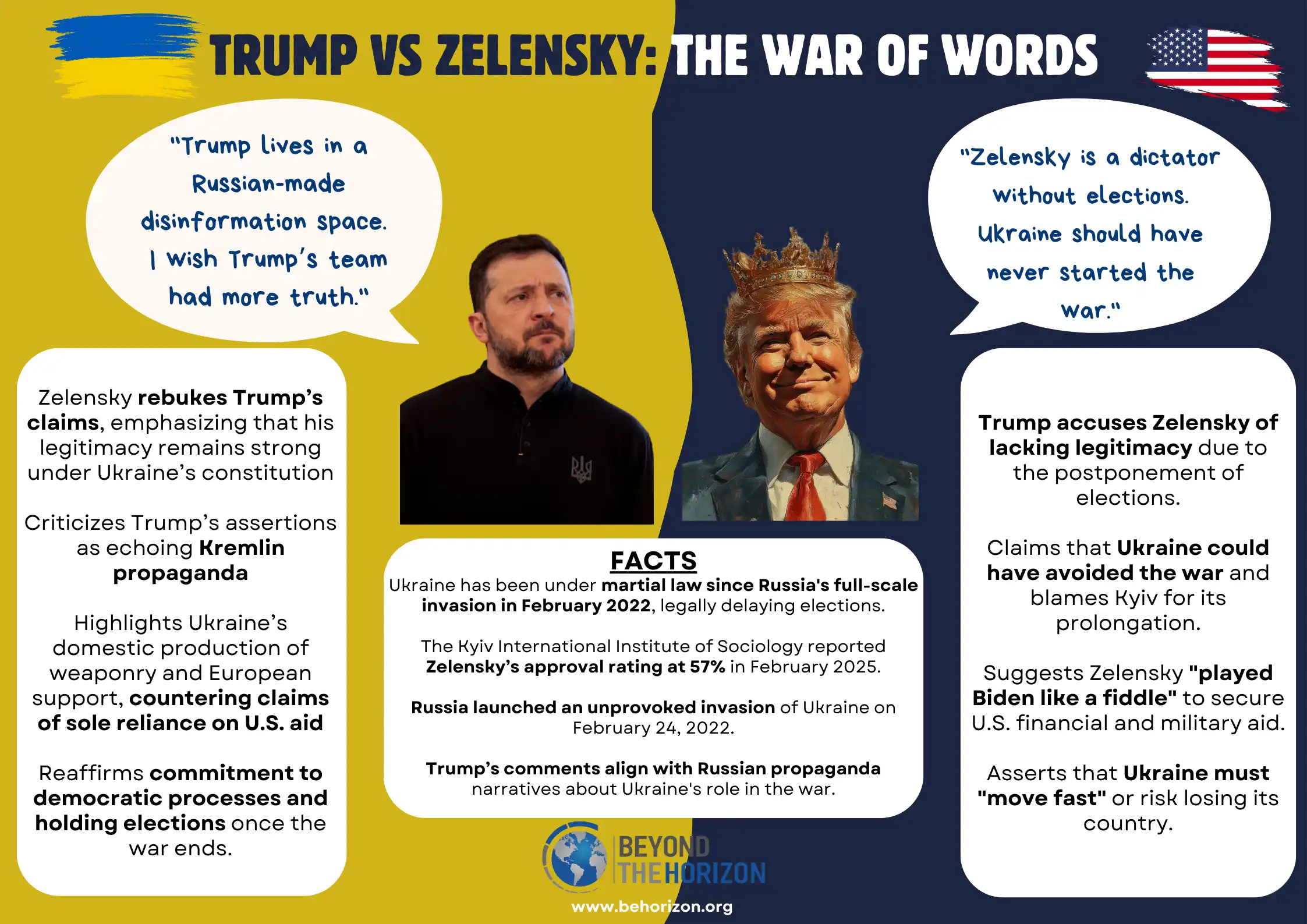

European Defense Response: Anticipating a more insular Washington, Europe is already moving toward greater self-reliance in defense. The EU’s Joint White Paper on European Defence Readiness 2030 notes that the United States “believes it is over-committed in Europe and needs to rebalance” its role. As a result, EU nations are “investing massively in [their] defense” and seeking a stronger EU security architecture. Initiatives to improve military mobility, joint capabilities, and even discussions of an independent European deterrent have gained momentum. However, Europe’s build-up will take time, and a transatlantic rift could leave a short-term security gap. Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine (and any future aggression) tests Europe’s readiness. If the U.S. sharply cuts support to Ukraine or pursues a unilateral peace deal with Moscow, it could force Europe to shoulder the burden of containment. In the worst case, a Trump–Putin understanding “behind Europe’s back” is feared, possibly resulting in Ukrainian territorial concessions that many Europeans would find unacceptable.

Arms Sales and Military Posture: A transactional U.S. approach may link security commitments to economic deals. Trump could use troop presence in Europe as leverage – for example, hinting at redeployments unless allies buy more American weapons or comply with U.S. policy preferences. Countries like Poland and the Baltic states, who feel most exposed to Russia, might rush to purchase U.S. arms or host bases (resurrecting ideas like “Fort Trump”) to secure American favor. Conversely, if allies resist U.S. demands, Washington might scale down exercises or readiness, weakening NATO’s deterrence posture by default. Overall, Europe’s security landscape in 2025–2029 would feature greater uncertainty, a more pronounced EU defense role, and a Russia potentially testing the limits of Western cohesion.

Indo-Pacific Deterrence and Alliances

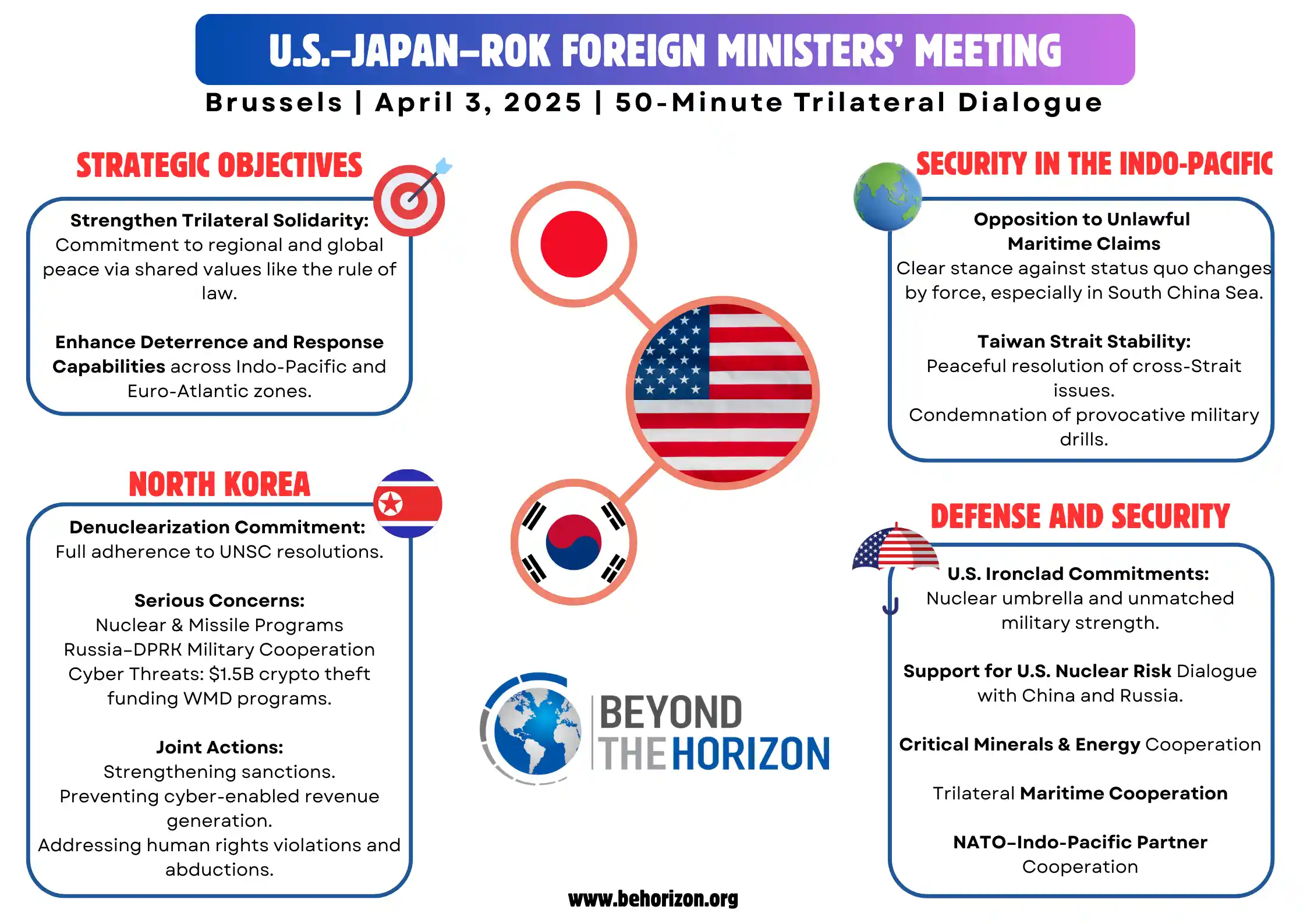

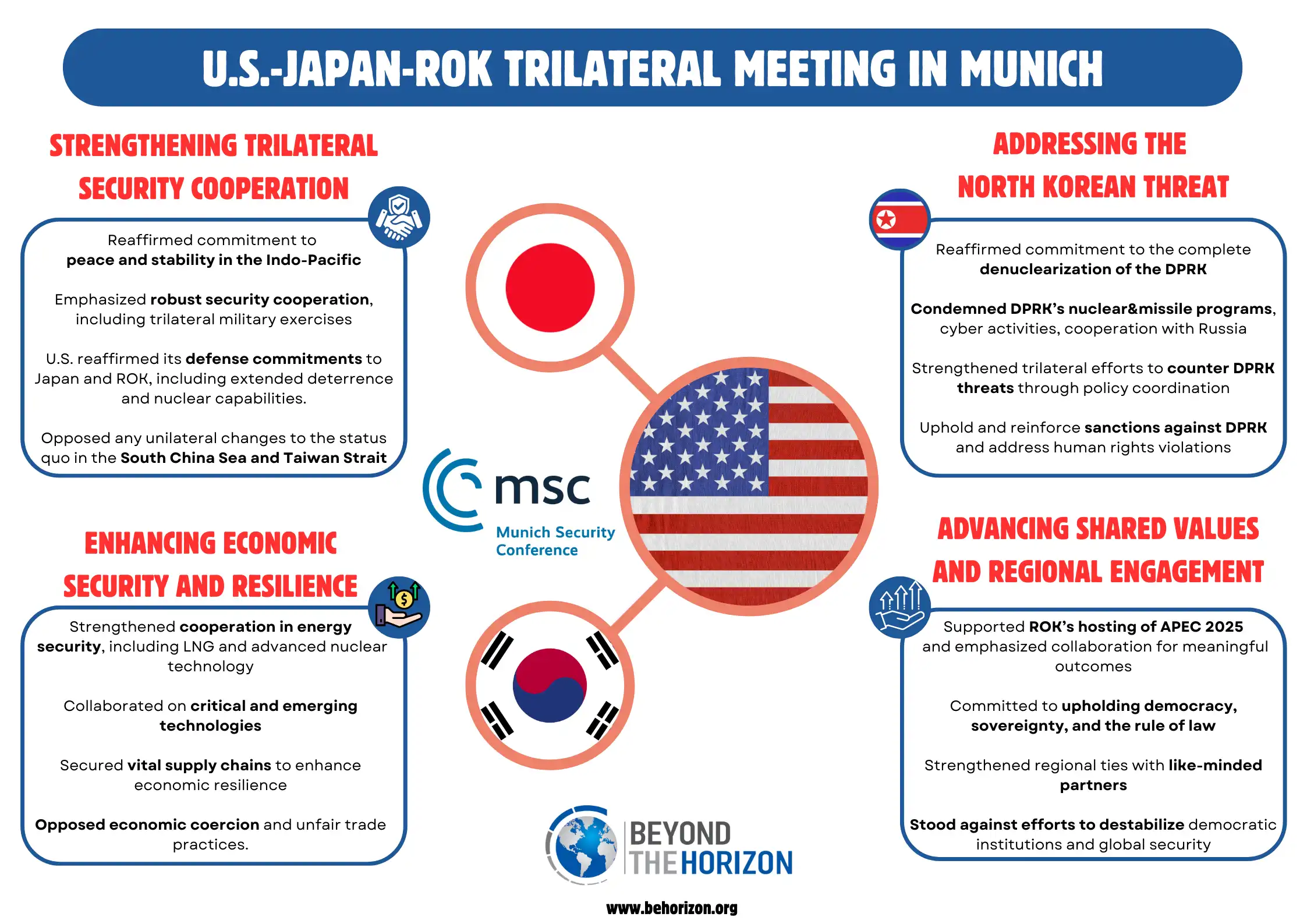

Focus on China – and Alliance Tensions: In the Indo-Pacific, the Trump administration would continue prioritizing the containment of China as a top strategic goal. U.S. military posture in Asia is likely to remain robust – expect freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea, heightened support to Taiwan, and closer defense ties with Australia, Japan, and India (through mechanisms like the Quad). However, as in Europe, the style may be disruptive. Trump’s unilateralism and deal-making approach could unsettle Asian allies. Officials and experts worry that Trump’s “reluctance to engage in foreign conflicts” and skepticism of alliances could “undermine the United States’ commitments to security alliances, particularly in Asia.” South Korea and Japan might face pressure to pay more for U.S. troop basing – straining those alliances – even as they rely on the U.S. nuclear and conventional deterrent against North Korea and China. Any indication of U.S. pullback or inconsistency (for example, a sudden outreach to North Korea or China without consulting allies) would raise doubts in Seoul and Tokyo about American reliability.

Regional Flashpoints: A more confrontational stance toward Beijing could heighten the risk around key flashpoints. Trump’s team has signaled a more assertive approach toward Taiwan – potentially expanding military aid or diplomatic recognition. While this would bolster Taiwanese morale, it could provoke aggressive Chinese responses, from military drills to coercive economic measures, increasing cross-strait tensions. In the South China Sea, U.S. naval presence will likely grow, possibly joined by partners like Japan and Australia to assert freedom of navigation. This could lead to more incidents with Chinese forces in disputed waters. On the Korean Peninsula, Trump might revive high-level summits with Kim Jong-un to strike a denuclearization “deal.” Such top-down diplomacy, as seen in 2018–2019, could sideline South Korea and spark an arms race if it falters. Japan and South Korea, under threat from North Korean missiles, could contemplate stronger independent defense capabilities (even nuclear options have been debated quietly) if U.S. commitments waver.

Indo-Pacific Coalitions: Despite these uncertainties, a second Trump administration would also see attempts to reinforce Indo-Pacific coalitions against China. The first Trump term established or reinvigorated concepts like the Quad (U.S.-Japan-Australia-India) and promoted the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.” These are likely to continue. Heightened military cooperation and strategic partnerships are expected as the U.S. tries to counterbalance China’s regional assertiveness. For example, we may see more frequent joint exercises (such as U.S.-India naval drills in the Indian Ocean), intelligence-sharing (e.g. expanding Five Eyes partnerships) and defense technology deals with allies. The risk, however, is that Trump’s transactional style may lead some Asian partners to hedge their bets. If U.S. policy is seen as too erratic or solely self-interested, countries in Southeast Asia may be reluctant to align too closely, preferring to keep engagement open with Beijing. The net effect on Indo-Pacific security will be a delicate balance: U.S. power projection continuing, but the credibility of U.S. commitments under question, which China will undoubtedly seek to exploit.

Economic and Trade Shifts

Transatlantic Trade War and Global Supply Chains

Tariffs on Allies: Economic friction between the U.S. and Europe is set to escalate. President Trump has already previewed aggressive measures – for instance, announcing a 25% tariff on all imported automobiles and parts shortly before taking office in 2025. This move directly targets major European and Asian exporters. The EU (especially Germany, home to Volkswagen, BMW, Mercedes) would be hard hit, as would Japan and South Korea which count the U.S. as a top auto market. European officials reacted with dismay: “Tariffs are taxes – bad for businesses, worse for consumers, in the US and the EU,” warned European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, vowing to safeguard Europe’s interests. Canada likewise called the auto tariff a “direct attack” on its workers and promised retaliatory levies. We can expect a tit-for-tat tariff war: the EU and other partners will impose counter-tariffs on U.S. goods (from agriculture to technology) if broad U.S. import taxes persist. This would disrupt transatlantic commerce that, until recently, was deeply intertwined and largely free of such barriers.

Global Supply Chain Disruptions: A full-fledged tariff war would reverberate through global supply chains. Modern manufacturing is transnational – for example, even “American-made” cars rely on foreign parts. A 25% tariff on autos and parts means higher costs and price spikes for consumers and firms on both sides of the Atlantic. Industries from automotive to machinery and luxury goods (wines, cheeses, industrial equipment) could face shortages or rising input costs. Some companies may shift production to the U.S. to bypass tariffs, but such reorganization is costly and time-consuming. Trade uncertainty is already dampening business confidence: in early 2025, U.S. consumer confidence fell to its lowest in four years amid fears of recession and higher inflation driven by tariffs. Should the tariff regime endure, Europe might accelerate efforts to reduce dependence on the U.S. market – diversifying export destinations and fortifying its internal market. Likewise, U.S. firms might seek alternate suppliers (e.g., sourcing more from Mexico or ASEAN countries instead of Europe or China). Over 2025–2029, we are likely to see a decoupling of some U.S.-Europe supply links and a reorientation of trade flows, as each side adapts to a more protectionist U.S. stance.

Retaliation and Mitigation: Other major economies are already preparing measures in response to U.S. protectionism. In Asia, U.S. allies have shown a mix of concessions and counter-moves: for instance, South Korea tightened origin rules (to ensure its exports are seen as local, not Chinese re-exports) while India and Vietnam preemptively lowered some tariffs on U.S. goods to appease Washington. The U.K., caught between wanting a U.S. trade deal and its own digital services tax on tech giants, has signaled it might adjust policies to avoid Trump’s ire. Meanwhile, the EU has compiled lists of U.S. products for retaliatory tariffs, aiming to pressure politically sensitive sectors in America. The broader implication is a breakdown of the rules-based trading system: Trump’s go-it-alone tariffs violate WTO norms, and if multiple countries retaliate in kind, global trade governance (already weakened by a paralyzed WTO Appellate Body) will erode further. The world could enter 2026 in a tariff-induced economic slowdown, with growth dampened in the U.S., Europe, and beyond. This would be a stark reversal from the relatively cooperative trade environment of past decades.

Indo-Pacific Trade Re-alignments

Asia’s Collective Response: Facing U.S. tariffs and “decoupling” pressures, Asian powers are banding together to bolster regional trade. In March 2025, China, Japan, and South Korea held their first high-level economic dialogue in five years, reaching a consensus to “jointly respond” to U.S. tariff actions. They agreed to strengthen supply chain cooperation and coordinate on export controls, effectively creating a united front among East Asia’s largest economies. Notably, Japan and South Korea – both U.S. allies – signaled interest in importing more semiconductor raw materials from China, while China would buy more high-end chips from them. This kind of arrangement suggests that U.S. trade restrictions are incentivizing Asian integration: erstwhile rivals are setting aside some disputes to ensure critical supply chains (like electronics and automotive components) remain intact despite U.S. barriers. Additionally, the three countries agreed to reinvigorate talks on a long-stalled China-Japan-South Korea Free Trade Agreement and to reinforce the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a 15-nation Asian trade bloc. Trump’s tariffs, dubbed a “liberation day” from past trade practices by Washington, have ironically liberated momentum for Asia’s intra-regional trade deals.

US-China Trade War 2.0: Under Trump 2.0, the simmering trade war with China will likely escalate. Tariffs on Chinese goods had already been raised to 20% across-the-board by early 2025. Beijing has retaliated in kind, for example imposing up to 15% duties on U.S. farm exports like poultry and pork. We should expect further rounds of tit-for-tat tariffs and restrictions. The U.S. may expand tariffs to “phase out all Chinese imports of essential goods” over four years (a goal Trump has proclaimed). China could counter by curbing exports of critical materials (as it began doing with rare earth minerals and metals crucial for tech manufacturing) or by targeting U.S. companies in China. This decoupling will fragment the Asia-Pacific economic landscape: supply chains that run through China will be re-routed where possible through countries like Vietnam, India, or Mexico. Southeast Asian nations might benefit in the short term by capturing investment as firms seek non-tariffed bases. Indeed, parts of ASEAN could see a surge of factories relocating from China to avoid U.S. duties, a trend already underway. However, these economies also risk secondary fallout from reduced Chinese demand and general global uncertainty. Moreover, if U.S. tariffs start hitting friendly countries (e.g. tariffs on Japanese and Korean goods as threatened), those allies might retaliate or turn more toward China’s market, complicating U.S. influence in the region.

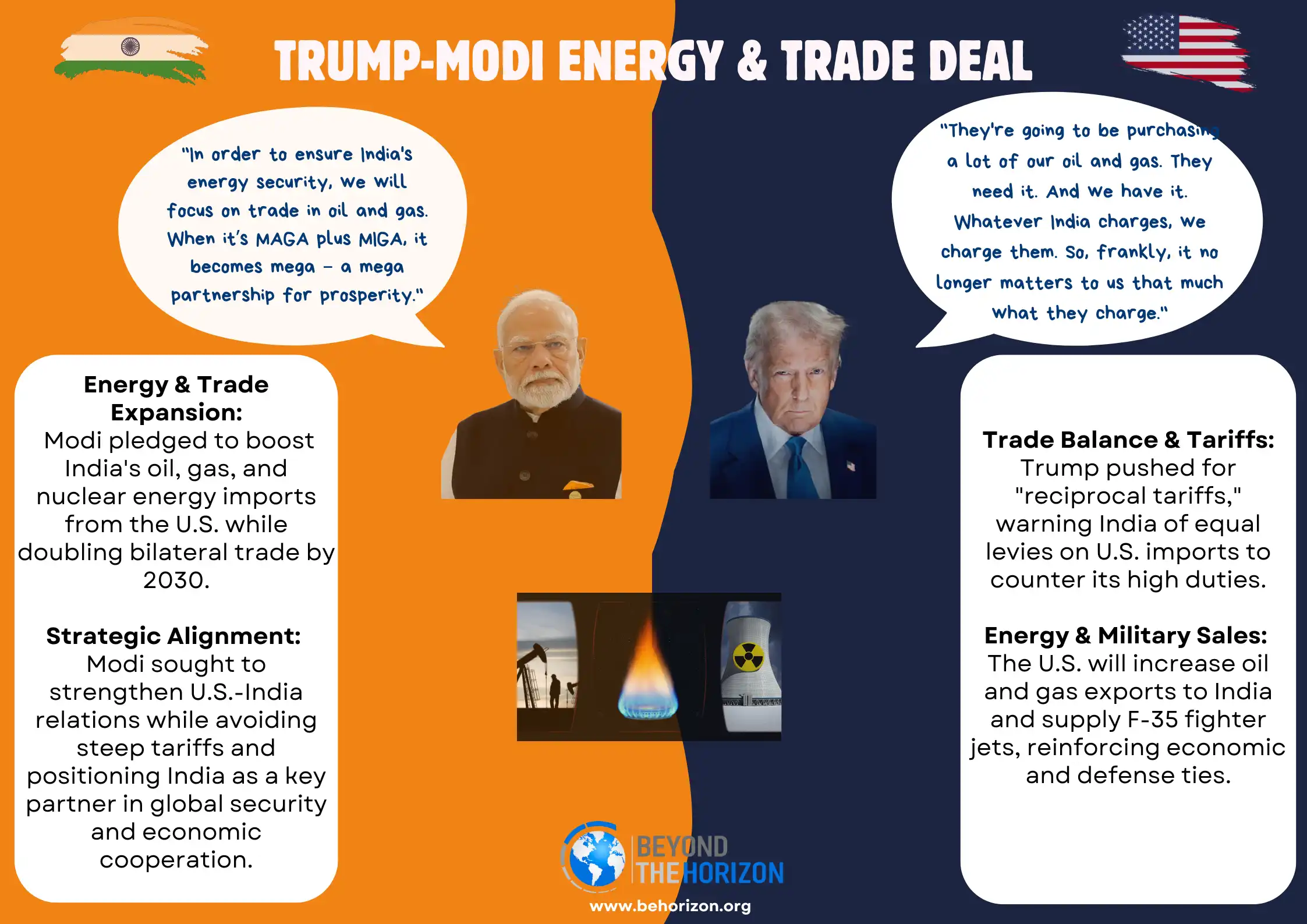

Energy and Other Sectors: Trade policy under Trump will also affect global energy and commodities markets. Trump’s skepticism of climate initiatives and focus on reviving fossil fuels could see the U.S. increase oil and gas exports (competing with Russia and OPEC) while slapping tariffs on imports of green tech (for instance, solar panels or electric vehicles from China and Europe). In 2024, the EU launched an anti-subsidy probe into Chinese EVs and even mulled tariffs; a Trump tariff on foreign EVs in the U.S. would likewise protect Detroit but could slow global EV adoption. Agricultural trade might be another battleground: China may cancel Boeing orders or stop buying American soybeans, pushing those purchases to Brazil or Europe, while the U.S. could restrict Chinese seafood or agricultural imports. Retaliatory measures will cross sectors, creating an unpredictable environment for businesses. Countries like India will try to leverage the situation – negotiating trade pacts with the U.S. (as seen in talks for a multi-sector agreement focusing on tech and agriculture), even as they maintain commerce with China and Russia. This nimble, interest-based repositioning is emblematic of how middle powers will navigate the Trump-era economic tempest: by seeking maximum benefit from both great powers while avoiding being shut out by either.

Technological Decoupling and Cooperation

Strategic Tech: Semiconductors and AI

Semiconductor Supply Chain Split: Technology is a core arena of U.S.-China competition that will intensify under Trump’s second term. The U.S. is intent on maintaining dominance in semiconductors, the “brains” of modern devices, and preventing China from acquiring cutting-edge chips. Trump’s team has already moved to tighten export controls on advanced chips and the equipment to make them. We will likely see even stricter limits on technology transfer to China, building on prior bans (e.g. on Huawei and other Chinese tech firms). This will put allies in a bind: for example, the Netherlands’ ASML (a key producer of lithography machines) and Japan’s Nikon may face U.S. pressure not to sell certain tools to China. Likewise, South Korean and Taiwanese chipmakers will be pressed to choose between access to U.S. technology and the lucrative Chinese market. In parallel, Trump is launching initiatives to shore up U.S. chip capacity. The administration is pursuing sector-specific trade agreements focusing on securing semiconductors and critical minerals with partners like India and possibly the UK. The aim is to create a U.S.-led bloc of trusted chip supply, reducing reliance on China’s materials and manufacturing. This decoupling means the world’s semiconductor ecosystem could bifurcate: one supply chain centered on the U.S. and allied countries (Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, India), and another centered on China (which is investing heavily in homegrown chips). In the short term (2025–2026), U.S. export curbs will hurt Chinese tech firms’ access to top-tier chips for AI and 5G. But China may retaliate by banning exports of its own critical tech inputs. In fact, China has already signaled it might restrict exports of gallium and germanium – metals crucial for semiconductor production – and the equipment for refining such minerals. This tech tug-of-war will force other countries to adapt. Europe, for instance, has advanced chip companies (like ASML or Germany’s Infineon) and will try to protect its industry while complying with allied export controls. The EU may double down on its “Chips Act” to build more fabs in Europe, seeking tech sovereignty in case U.S.-China decoupling cuts it off from either side.

Artificial Intelligence and Cyber: AI is another frontier where U.S. policy will shift toward rivalry. A Trump-led U.S. may curtail research cooperation with China in AI and quantum computing, tightening visa controls on Chinese researchers and sanctioning companies involved in advanced computing with military uses. We might see efforts to create an alliance of “AI democracies” to set standards and pool talent, excluding China. Conversely, China will push its own AI ecosystem and standards, from facial recognition tech to autonomous systems, often exporting them through the Belt and Road Initiative digital projects. This could result in competing AI spheres: one where Western norms of transparency and privacy attempt to hold (often championed by Europe’s regulations), and another where China’s more surveillance-oriented approach is adopted by authoritarian-leaning states. Cybersecurity tensions will remain high – with potential escalation in state-backed hacking on both sides. U.S. allies will be urged to keep Chinese 5G and cloud providers out (a campaign already underway), even as China offers its tech to willing buyers. The Trump administration’s stance of viewing technological interdependence as a security liability means less global tech cooperation on issues like setting international AI rules or coordinating on cybercrime, at least in forums involving China or possibly Russia.

Critical Minerals and Green Technologies

Critical Minerals Race: Critical minerals (like lithium, cobalt, rare earths) are the backbone of future industries – from EV batteries to missiles. The U.S. is moving assertively to secure these supply chains at home or with allies. In March 2025, Trump signed an executive order invoking the Defense Production Act to boost domestic mining and processing of critical minerals. Moreover, new bilateral deals are being negotiated: for example, the U.S.-India trade talks included plans for cooperation in sourcing and processing critical minerals. The Atlantic Council notes that Washington’s strategy is to put “advanced technologies and their critical inputs front and center” in trade policy to counter China. China currently dominates global refining of many rare minerals (over 60% of lithium processing, 70% of cobalt, 90% of some rare earths). To reduce this leverage, the U.S. will invest in alternate sources (Australia, Canada, Africa) and encourage allies to coordinate on export controls and stockpiling of critical minerals. For Europe and Asia, this is a double-edged sword: it’s an opportunity to collaborate with the U.S. on new mining projects or recycling initiatives, but it may also mean pressure to exclude China from mineral supply chains. Countries like Australia (rich in lithium) and Indonesia (nickel) could gain from new partnerships, whereas China might respond by further restricting raw materials to nations partaking in the U.S.-led coalition. By 2029, we could see a more regionalized critical mineral trade: North America and allies sharing resources, while China deepens ties with mineral-rich Global South partners that the U.S. has not secured.

Climate and Green Tech Divide: Climate technology is another area likely to see transpacific divides. With Trump exiting the Paris Agreement and favoring fossil fuel industries, U.S. policy will prioritize oil, gas, and coal production. Subsidies and support for renewable energy (solar, wind) and clean tech may be rolled back compared to the previous administration’s efforts. This could cede ground to Europe and China, who are pressing ahead in green tech. Europe remains committed to its Green Deal, aiming to lead in renewable deployment, electric vehicles, and carbon reduction. China also invests massively in green tech (it’s the world’s largest producer of solar panels, EV batteries, and is scaling up wind and nuclear power). Paradoxically, a U.S. retreat on climate cooperation could let China and Europe collaborate more – for instance, on electric vehicle standards or solar financing – even as they compete economically. Europe has already confronted China on issues like cheap EV imports, but both sides share an interest in countering climate change that the U.S. federal policy will lack. Additionally, international climate finance and agreements (like COP summits) will proceed with diminished U.S. leadership; China might step in diplomatically to champion certain green initiatives in developing countries, gaining soft power. However, in the U.S. absence, achieving aggressive global emissions targets becomes harder. Technologically, the split could mean divergent paths: one where the U.S. doubles down on traditional energy and perhaps nascent tech like carbon capture for oil, and another where the EU/China race to dominate clean energy technologies. Countries in Asia and Europe might also find U.S. trade barriers on green goods – for example, if Trump imposes tariffs on imported electric vehicles or solar panels to protect U.S. makers, it could slow the diffusion of those technologies.

Cooperation versus Decoupling

The technological landscape will be defined by a tension between cooperation and decoupling. Some U.S. allies and partners will try to maintain cooperation – for instance, South Korea and Japan’s agreement with China to engage in more dialogue on export controls and supply chain stability shows a pragmatic approach to keep tech flows open. The EU will also walk a fine line: it shares U.S. concerns about certain Chinese tech practices and has its own investment screening and 5G restrictions, but it does not want to be forced into a wholesale cut-off. The concept of “digital strategic autonomy” in Europe means building indigenous capabilities (in cloud computing, AI, chips) so as not to be overly dependent on either the U.S. or China. Meanwhile, the U.S. drive for decoupling in critical tech is clear – aiming to bifurcate the world’s tech and industrial systems into blocs. By 2029, we may see two parallel technology universes to a greater extent than today: for example, one ecosystem using Western-made chips, software, and following democratic data norms, and another using Chinese/Russian-made chips and state-centric norms. This has implications beyond economics – it could solidify an ideological divide where technology and internet governance align with political values (open vs. authoritarian). Countries outside the U.S.-China duel (like in the Global South) will be caught in between, perhaps using a mix of technologies from both sides. Managing this split without a complete collapse of global innovation networks will be a key challenge. Some areas might still see cooperation – global standards bodies, scientific research on climate or health – but even those could become arenas for competition over influence.

China’s Strategic Opportunism and Global Reactions

As the United States shifts course, China is poised to capitalize on any rifts or vacuums in global leadership. Beijing’s strategy under Xi Jinping is adaptive: pursue opportunities for gain while managing the risks of instability. A second Trump administration offers China a mix of both.

Exploiting Transatlantic Rifts: If U.S.-EU relations sour due to tariffs or security disputes, China will present itself as an alternative partner for Europe. Chinese diplomacy is already wooing Europe with messages of respect and cooperation. “China regards Europe as an important pole in a multipolar world, and supports Europe in maintaining its strategic autonomy,” Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his European counterparts. We can expect China to deepen bilateral ties with key EU members through investment, market access promises, and strategic dialogues. For example, China might offer Germany and France greater roles in initiatives like the Belt and Road or partnerships in Africa, implicitly saying: we can prosper together, despite U.S. protectionism. At the same time, Beijing will encourage EU independence on issues like Iran and climate, where it often aligns more with Europe than with Trump’s Washington. European leaders, while cautious of China’s rise, have shown “renewed interest” in engaging Beijing as transatlantic ties falter. Beijing will try to leverage this interest to prevent a united Western front against it. However, Europe’s openness has limits – China’s positions on Ukraine and human rights are major sticking points. Still, any daylight between the U.S. and EU is a strategic opening China will nurture with high-level visits, economic carrots, and diplomatic assurances.

Deepening Influence in Asia-Pacific: In Asia, China will seize on any U.S. retreat or inconsistency to assert regional leadership. Already, U.S. allies Japan and South Korea have felt compelled to hedge: their foreign ministers met with China to seek “common ground” as “the international situation has become increasingly severe” with Trump’s policies. China will encourage such regional cooperation that excludes the U.S. For instance, Beijing is championing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and even proposing to expand it. If the U.S. remains outside Asian trade pacts (having withdrawn from TPP earlier), China gains by setting the rules of regional trade. Likewise, Beijing could mediate or involve itself in regional hotspots – possibly trying to broker talks in the Korean Peninsula or offering ASEAN a code of conduct in the South China Sea – projecting an image of a stabilizing power. Notably, when Trump rattled allies, “China, Japan and South Korea agreed to jointly respond to U.S. tariffs,” coordinating policies to uphold trade. Such cooperation, facilitated by China, enhances Beijing’s stature as a regional linchpin. Additionally, if U.S. bilateral alliances weaken, China may find receptivity in countries like the Philippines or Thailand to tilt back toward China’s orbit, in exchange for economic incentives or security assurances.

Global Institutions and Norms: A less engaged or more combative U.S. on the world stage gives China room to increase its influence in international institutions. During Trump’s first term, when the U.S. withdrew from bodies like the UN Human Rights Council, China stepped in to take more prominent roles. This is likely to recur. China will advocate for its vision of global governance – emphasizing sovereignty and economic development over liberal political norms – in forums from the UN General Assembly to the BRICS. It has already framed U.S. actions as “unilateralism” that must be resisted. If the WTO remains weakened, China may champion alternative trade dispute mechanisms (perhaps through bilateral deals or regional structures where it has sway). On climate change, with the U.S. federal government pulling back, China could attempt to wear the mantle of climate leadership by adhering to its carbon pledges and financing green projects abroad – though its domestic coal use tempers this image. Furthermore, Beijing and Moscow’s strategic partnership might grow stronger in the face of U.S. pressure. The two have found common cause in deflecting Western sanctions and NATO expansion. Should Trump ease pressure on Russia, China benefits by having a less encumbered Russian partner; if instead U.S.-Russia ties sour differently, China still wins as Russia leans more on China economically and militarily. In either case, China and Russia together will promote a post-Western international order whenever U.S. leadership wanes.

Opportunities and Risks for Others: The shifting landscape is not only about China. Other actors will also maneuver. Russia, if U.S. focus on NATO diminishes, gains a freer hand in Eastern Europe – potentially consolidating its hold on parts of Ukraine or testing NATO’s resolve elsewhere. India might leverage U.S.-China rivalry to its benefit, securing technology transfers and investments from a U.S. keen to court India, while also retaining ties with Russia and access to multiple markets. Middle Powers like Australia, Canada, and South Korea will coordinate among themselves more: for example, we may see greater Australia-Japan-India security cooperation to compensate for any U.S. unpredictability in Asia. The international economic institutions will also feel the change – the IMF/World Bank might see challenges to Western norms as China and others push for more influence or create parallel institutions (like the AIIB, New Development Bank).

Overall, China stands to benefit in relative terms from a more isolationist or divisive U.S. approach: it can portray the U.S. as an unreliable actor and itself as a stable partner. However, Beijing must also manage significant risks. A confrontational U.S. stance could lead to a hard containment line around China, with powerful militaries (U.S., Japan, India, Australia) wary of its moves. An unstable global economy from trade wars could harm China’s export-driven growth. And if Trump’s policies inadvertently unite U.S. allies in opposition (rather than divide them), China could face a more solid coalition against it. Thus, Xi Jinping’s government will likely proceed with a mix of assertiveness and caution – pushing forward where U.S. influence ebbs, but avoiding direct conflict while America is unpredictable.

Conclusion: Outlook and Strategic Considerations

The 2025–2029 period under a second Trump administration promises to be a watershed in global geopolitical dynamics. We are likely to witness the further unravelling of the post-1945 U.S.-led order in favor of a more fragmented, multipolar system. U.S. “America First” policies, emphasizing national advantage in security, trade, and technology, will test the resilience of alliances and international institutions that have underpinned global stability for decades. Europe and the Asia-Pacific will be at the forefront of this transition. For Europe, the era of assuming U.S. security guarantees and open markets may be over; it faces the dual challenge of boosting its defense capacity while defending its economic interests amid U.S. tariffs and extraterritorial demands. For the Asia-Pacific, the U.S.-China rivalry will dominate, forcing regional states to navigate an uneasy balance between a sometimes overbearing ally and an ever more influential neighbor.

Policymakers worldwide should prepare for a period of heightened uncertainty. This includes developing contingency plans for various scenarios: a partial U.S. retreat from Europe, a protracted U.S.-China trade and tech standoff, or even crises like a flare-up over Taiwan or a breakdown in Korea talks. Cooperative mechanisms among middle powers (such as EU coordination on defense, or Asian regional forums without the U.S.) may serve as stabilizing factors. The key will be maintaining as much international cooperation as possible in areas of common interest – be it preventing nuclear proliferation, combating climate change (even if led by Europe/China), or managing pandemics – despite the more transactional and bilateral U.S. approach.

In summary, second Trump administration will usher in significant shifts in global geopolitics: security alliances recalibrated, economic linkages reconfigured, diplomatic norms challenged, and technological systems divided. China is poised to both fill voids and face pushback in this environment. The implications for the EU, NATO, and Indo-Pacific allies are profound, requiring proactive adaptation. While the coming years could see greater instability and rivalry, they also provide an impetus for other nations and groupings to step up in shaping a balanced, albeit more multipolar, world order. The stakes for global peace and prosperity will hinge on how these players respond to the disruption and whether they can collectively manage the risks of this new geopolitical era.

Related Infographics