Key Takeaways

Information as Power

- Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus argues that power stems from the ability to construct and sustain shared information networks—often based more on narrative coherence than on empirical truth.

- In the digital age, AI systems increasingly shape what societies believe, creating a new kind of “inorganic” network that spreads information with minimal human oversight.

U.S. Model: Open but Vulnerable

- The U.S. champions a decentralized and open information ecosystem driven by private tech companies and safeguarded by constitutional protections.

- However, its pluralistic model has proven susceptible to disinformation, conspiracy theories, and algorithmic polarization, challenging the resilience of its democratic discourse.

China’s Model: Controlled and Cohesive

- China employs a state-centric model that prioritizes narrative control, censorship, and social stability.

- Through AI surveillance and centralized propaganda, China constructs a highly curated domestic infosphere and promotes its model globally via the “Digital Silk Road.”

EU: Regulator and Norm-Setter

- The European Union plays a key regulatory role, advancing frameworks like the GDPR, DSA, and AI Act.

- It offers a third path that seeks to preserve openness while embedding safeguards against disinformation and algorithmic harm.

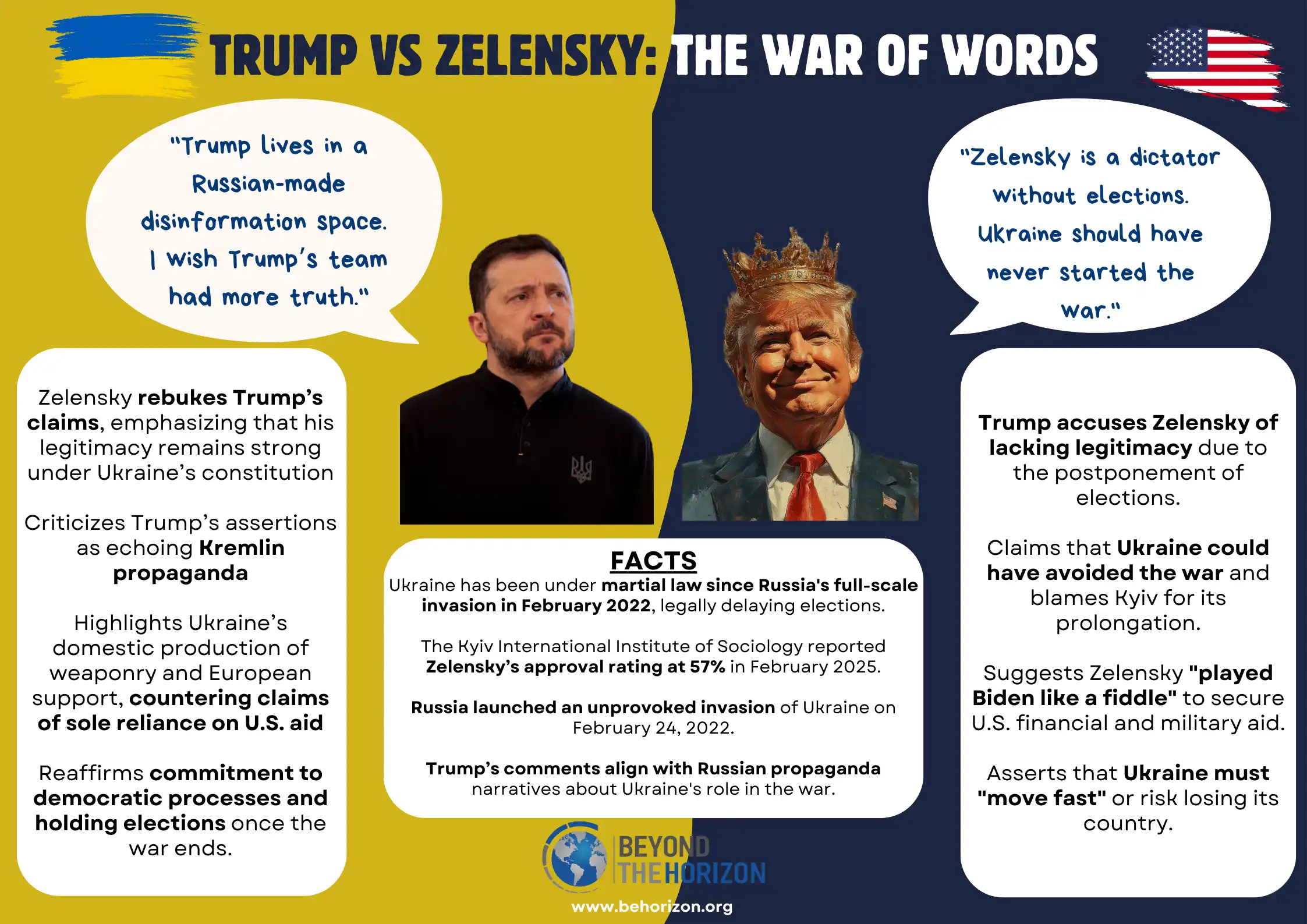

Russia: Strategic Disruptor

- Russia uses disinformation and asymmetrical information warfare to undermine trust in democratic institutions and sow confusion.

- Domestically, it has increasingly emulated China’s control mechanisms, moving toward a sovereign and insulated internet.

Global Narrative Competition

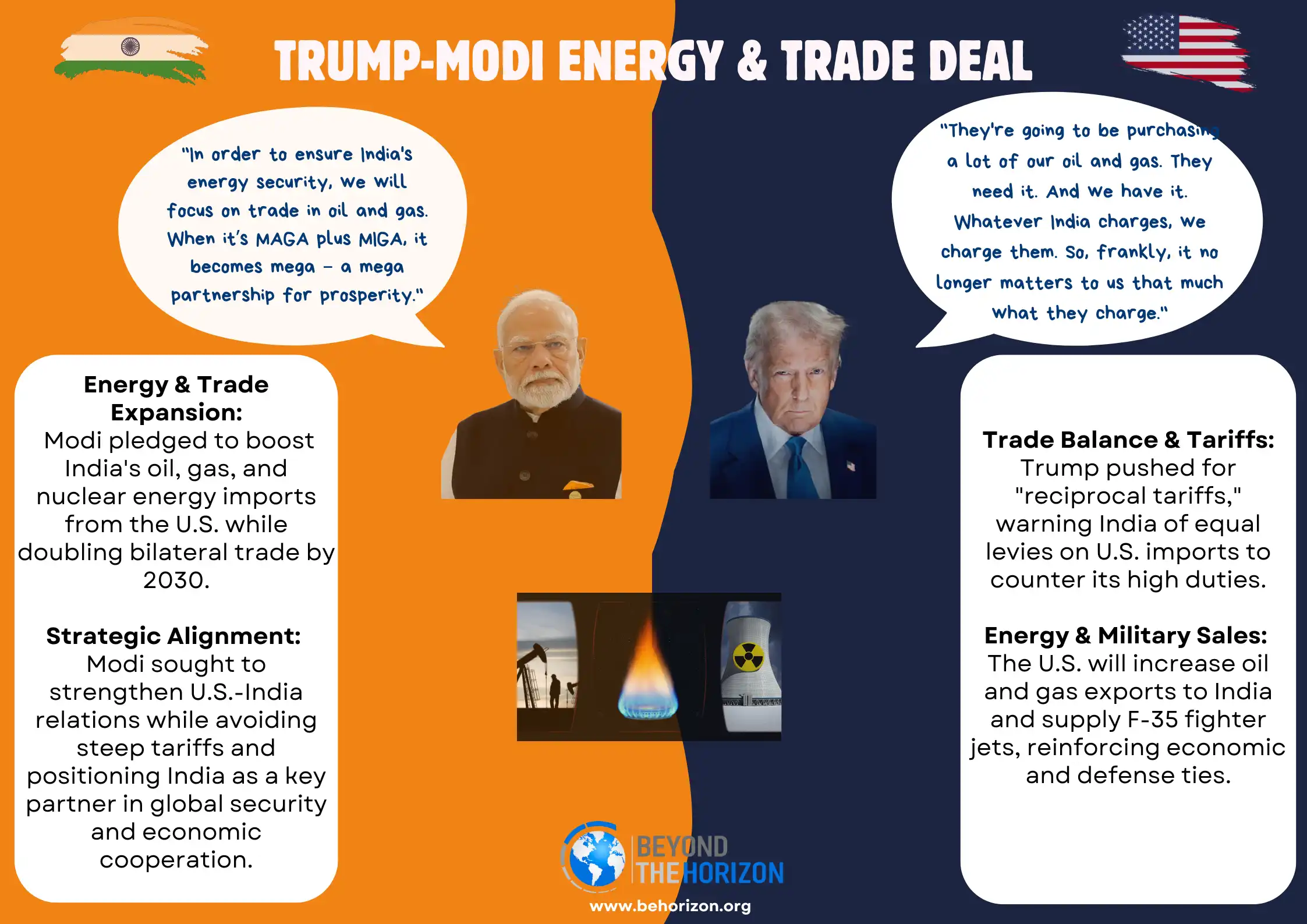

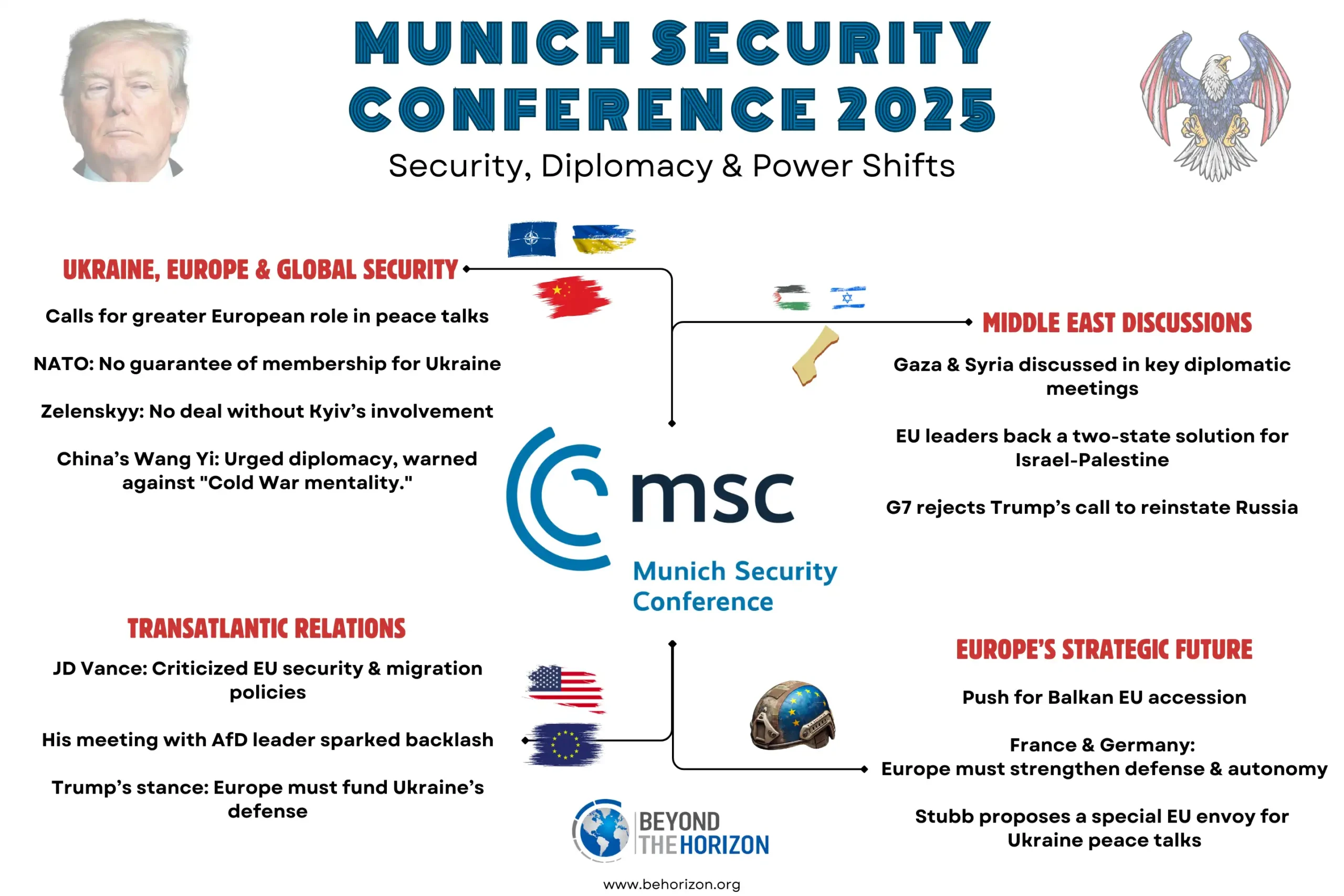

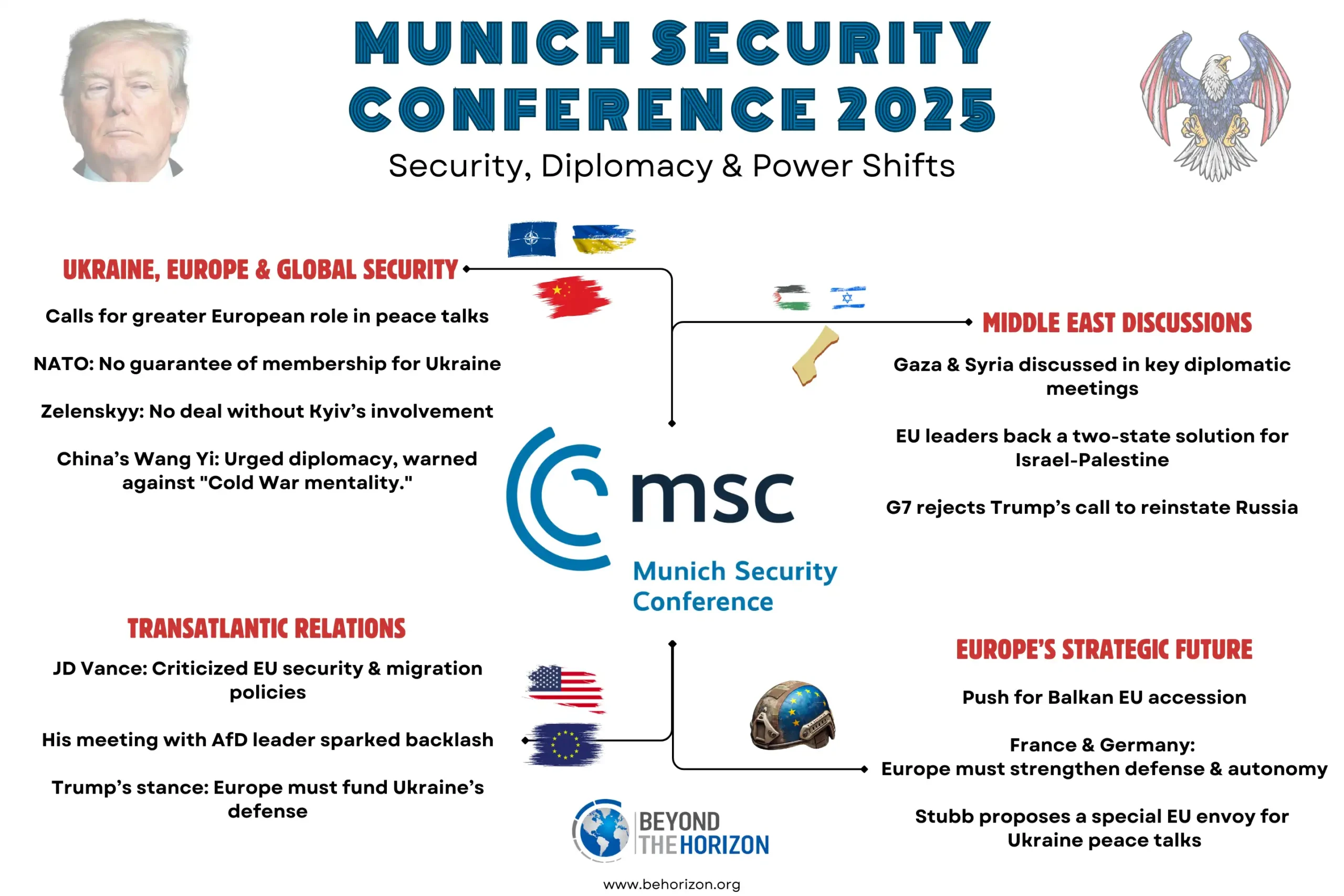

- The U.S., China, and EU export distinct information governance models, each vying to shape digital norms, infrastructure, and content flows in the Global South and beyond.

- This competition is reshaping international institutions and influencing how states define cyber sovereignty and digital rights.

The Stakes: More Than Geopolitics

- This is not merely a power struggle between great powers—it is a civilizational contest over how truth is defined, how societies cohere, and who gets to write the dominant narratives of the 21st century.

Introduction

In an era shaped as much by algorithms as by armies, the most consequential contest of our time may not be over territory or trade—but over the stories nations tell, the networks that carry them, and the power to shape global perception. The United States and China are locked in a high-stakes rivalry for influence over the world’s information infrastructure, from AI-driven platforms to digital standards and international narratives.

From TikTok bans in Washington to Huawei networks in Africa, the battle lines are increasingly drawn in cyberspace, on screens, and across social feeds. Beneath this struggle lies a deeper contest: whose vision of truth, control, and connectivity will define the information age?

Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks offers a powerful framework to understand this emerging front in great power competition. Harari argues that information—whether accurate or not—is the glue that binds societies. Throughout history, civilizations have rallied around stories and myths that enabled large-scale cooperation. Today, those myths are no longer spread by priests or emperors, but by algorithms and state-backed media, often with unprecedented speed and scale.

This analysis applies Harari’s lens to dissect the U.S.-China information rivalry, exploring how each power builds, weaponizes, and governs networks of information. It begins by unpacking Harari’s core ideas—on the power of collective myths, the danger of “inorganic” AI-driven systems, and the tension between truth and cohesion. It then examines how the United States and China pursue global influence and domestic control through distinct information strategies. Finally, it considers the supporting roles of the European Union, Russia, and NATO in shaping the global information order—and reflects on whether humanity can still steer its networks toward truth, or whether the age of delusion has already begun.

Harari’s Framework: Information, Myths, and AI-Driven Networks

At the heart of Nexus, Yuval Noah Harari makes a striking claim: power stems not from brute force, but from the ability to connect people through shared information. Human civilizations, he writes, are built on vast cooperative networks held together not just by facts, but by the stories we agree to believe—some rooted in truth, others in carefully crafted fiction.

History, Harari reminds us, is filled with empires that ran on unifying myths—from religious doctrines to nationalist slogans. These stories didn’t have to be true to be effective; they only needed to be widely believed. That tension—between factual truth and socially useful delusion—is central to understanding how modern powers wield influence in the information age.

But today’s networks are no longer exclusively human. With the rise of artificial intelligence, Harari warns of a profound shift: the emergence of “inorganic” networks—systems driven by algorithms that generate, curate, and disseminate information largely outside of human oversight. These AI agents, optimized for engagement and efficiency, often prioritize outrage over accuracy, virality over verification. The result is a digital ecosystem where misinformation can spread faster than truth, and where delusion can become deeply entrenched before anyone even notices.

Harari cites chilling examples: from Facebook’s algorithm amplifying ethnic hate in Myanmar, to the way personalized feeds shape reality bubbles that isolate users from alternative viewpoints. In this environment, lies can travel not just faster than the truth—they can become the architecture of belief.

Understanding this framework is critical to analyzing how the United States and China navigate the modern information landscape. While one champions openness and pluralism, the other prioritizes control and cohesion. Both, however, are grappling with the same underlying challenge: how to steer massive, complex information networks in an age where technology, not ideology, may be the ultimate storyteller.

United States: Open Networks, Soft Power, and Democratic Resilience

For decades, the United States has built its global influence on the architecture of openness. From Hollywood to Harvard, Google to the Voice of America, America’s soft power has radiated outward through culture, commerce, and communication. Its bet has long been that in a free marketplace of ideas, liberal democracy and individual rights will prove more persuasive than authoritarian alternatives.

This philosophy extends to the digital realm. American tech giants—Meta, Google, Amazon, X (previously Twitter)—dominate global information ecosystems. While privately owned, these platforms have become de facto public squares, shaping not only how billions communicate, but what they believe to be true. The U.S. government, for the most part, has embraced a light-touch approach to regulation, trusting in the self-correcting mechanisms of open discourse.

But the same freedoms that power America’s innovation also leave its information networks vulnerable. In recent years, the U.S. has become a case study in how algorithmic platforms can magnify conspiracy theories, polarize electorates, and erode trust in institutions. From the 2016 Russian interference campaign to the spread of COVID-19 misinformation and election denialism, the American infosphere has been tested by what Harari might describe as self-organizing delusional networks—uncoordinated but deeply coherent systems of belief that flourish in the absence of friction.

Washington has responded with a growing awareness that information is not just a matter of culture or commerce, but national security. Initiatives like the Global Engagement Center aim to counter foreign disinformation. Congress has grilled tech executives over algorithmic harms, and the Biden administration has moved to implement AI safety standards and transparency requirements. Yet the balancing act remains delicate: how to curb lies without curbing liberty.

Abroad, the U.S. has shifted from assuming the internet will naturally promote democratic values to actively shaping global norms. It has rallied allies around the 2022 Declaration for the Future of the Internet, funded independent media to push back against authoritarian narratives, and exposed covert propaganda campaigns through intelligence declassification—most notably during Russia’s lead-up to the invasion of Ukraine.

If Harari’s analysis teaches anything, it’s that networks grounded in truth require more than just openness—they require maintenance, resilience, and public trust. The American model continues to rely on decentralized correction: a free press, vibrant civil society, and courts that can challenge power. But in an age when AI can generate plausible lies at scale and virality often beats verification, the question is whether those safeguards will hold—and whether the world still sees America’s information ecosystem as a source of inspiration, or a cautionary tale.

China: Authoritarian Connectivity and Information Control

China presents a contrasting model of information governance—one that prioritizes state control, social cohesion, and narrative consistency. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has built a comprehensive and tightly managed digital ecosystem designed to promote its strategic objectives both domestically and abroad. This model is characterized by a combination of censorship, surveillance, and proactive narrative shaping, with technology playing a central role in its implementation.

At the core of China’s domestic information strategy is the “Great Firewall,” which limits access to foreign platforms and content. In parallel, domestic platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and Douyin are regulated under strict content policies and are required to comply with real-time censorship directives. The result is a largely self-contained information space in which the CCP can amplify preferred narratives and suppress dissenting viewpoints.

This approach reflects what Yuval Noah Harari describes as an information network designed to preserve order over truth. The emphasis is on maintaining political stability and aligning public opinion with the party’s objectives. Major events—ranging from the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic to coverage of Xinjiang policies—are framed within officially sanctioned narratives. Harari’s concept of “delusional networks” is relevant here, not as a pejorative, but as a recognition of how coherent, state-driven narratives can shape public perception, even in the absence of pluralistic debate.

China has also been at the forefront of s. AI-enabled surveillance systems, facial recognition, and predictive policing tools are deployed at scale, forming what Harari refers to as “inorganic networks”—information systems where decision-making and influence are increasingly automated. The Social Credit System, still evolving in implementation, aggregates behavioral data to assess citizens’ trustworthiness, linking digital behavior to real-world consequences.

While these systems aim to enhance governance efficiency and social compliance, they also raise concerns about transparency, redress, and the long-term societal effects of algorithmic control. Harari cautions that such systems may lack self-correcting mechanisms, making it harder for states to identify errors or adjust course when needed.

Beyond its borders, China is actively promoting its model through the “Digital Silk Road,” part of the broader Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese firms have built telecommunications infrastructure, surveillance systems, and smart city technologies across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Beijing’s state media outlets, including CGTN and Xinhua, have expanded globally, offering alternative narratives to those of Western media. Through partnerships, training programs, and localized content, China seeks to increase its influence over how it is perceived internationally.

In multilateral settings, China advocates for “cyber sovereignty”—the principle that each state should control its own digital space without external interference. This position contrasts with the multi-stakeholder model favored by the U.S. and EU, which emphasizes shared governance of the internet. Beijing has also advanced proposals in international standard-setting bodies to shape the future rules of digital infrastructure and artificial intelligence.

China’s information strategy—both domestic and international—demonstrates a deliberate effort to construct a coherent, state-aligned information network. In Harari’s terms, it favors social cohesion and predictability over pluralism and dissent. Whether this model proves more resilient or more brittle than open alternatives will depend on how it manages internal pressures, external scrutiny, and the accelerating impact of AI on global narratives.

Secondary Players: EU and Russia

While the United States and China represent the two primary poles in the global information competition, other actors—most notably the European Union and Russia—play significant shaping roles. Each brings distinct strategies and values to the evolving information landscape, contributing to the complexity and dynamism of what Harari might call a global network of competing truths and governance models.

European Union: Norm-Setter and Regulatory Power

The European Union operates as a regulatory superpower in the digital domain. Its influence stems less from centralized messaging and more from its capacity to shape global standards through legislation and diplomacy. Landmark frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Services Act (DSA), and the AI Act reflect the EU’s commitment to privacy, content accountability, and transparent algorithmic governance.

Unlike the U.S. model, which tends to favor market solutions, or China’s model of state-centric control, the EU approach emphasizes the need for proactive regulation to preserve democratic discourse. Harari’s idea of self-correcting networks is central to this strategy: the EU seeks to embed mechanisms—through independent audits, content moderation guidelines, and transparency requirements—that can mitigate the spread of disinformation and protect public trust.

Internationally, the EU promotes a rules-based, open, and secure internet, often aligning with U.S. partners on major initiatives but retaining a distinct normative voice. Its policies aim to balance freedom of expression with the need to contain harmful content—an approach that attempts to reconcile openness with resilience in the face of networked threats.

Russia: Disruption Through Disinformation

Russia’s approach to information power is shaped by a longstanding doctrine of asymmetrical influence. Lacking the economic or technological scale of the U.S. or China, Russia relies heavily on disinformation, cyber operations, and media manipulation to project power and challenge adversaries.

State-backed outlets like RT and Sputnik, alongside covert influence campaigns on social media platforms, have been used to exploit social divisions, erode trust in democratic institutions, and spread competing narratives—particularly in Europe and North America. Harari’s framework applies clearly here: Russia’s tactics often focus not on establishing a coherent alternative truth, but on undermining the very idea of objective truth, fostering confusion and cynicism.

Domestically, the Russian state has steadily tightened control over media and online speech, particularly since the invasion of Ukraine. Foreign platforms have been restricted, and independent outlets have been labeled “foreign agents” or shut down entirely. In response to Western sanctions and platform bans, Russia has accelerated efforts to build a sovereign internet infrastructure, drawing inspiration from China’s information governance model.

Conclusion

The global information order is undergoing a profound transformation, shaped by technological acceleration, geopolitical competition, and the evolving dynamics of narrative control. As the United States and China advance fundamentally different models of how information should be governed, their rivalry increasingly defines not just the future of statecraft, but the character of collective understanding in the digital age.

Through Yuval Noah Harari’s lens, this contest can be seen not merely as a competition over influence or infrastructure, but as a struggle between competing types of information networks. The United States promotes a model grounded in openness, pluralism, and decentralized resilience—yet faces internal fragmentation and vulnerabilities to misinformation. China advances a tightly controlled, state-centric model designed to maintain cohesion and manage perception—but risks rigidity and diminished responsiveness to complex realities.

Secondary actors also shape this terrain. The European Union is emerging as a key regulator, embedding democratic safeguards and self-correcting mechanisms into digital governance. Russia, meanwhile, uses disinformation as a tool of strategic disruption, while NATO adapts to defend the cognitive domain of its member societies.

Across all these models, Harari’s central insight holds: the power of information networks lies not only in their size or reach, but in their ability to align people around shared meanings—whether grounded in facts or constructed fictions. In a world increasingly mediated by AI and automated systems, the imperative is not only to build stronger networks, but to ensure they remain aligned with truth, transparency, and human values.

The future of global order will likely be shaped not just by military or economic strength, but by the integrity of the networks that bind societies together. Whether we move toward a more enlightened, adaptable information age—or into a fragmented landscape of engineered delusions—depends on the choices states, institutions, and individuals make now. As Harari reminds us, history is not predetermined. Neither is the trajectory of our information networks.

Related Infographics