The aim of this study is to propose a model by comparing “fixed force composition and classical HQ structures” with “a New modular design” that could increase and enhance capabilities and capacity of armed forces, in particular flexibility, adaptability, agility, and responsiveness against hybrid threats which have “freedom of choice” in a wide spectrum. In this study, following a review of the existing literature, I will examine Russian Hybrid Model in Eastern Ukraine and also touch upon the tactics and techniques of terrorist organizations such as ISIL and PKK/PYD which used hybrid tools as well. Unfortunately, hypotheses put forth could not be tested since; (a). There is not enough data to conduct these tests and, (b). Armed forces of different nations are reluctant to conduct field studies or share current available data on the subject. But I believe this study could be an initial step for further studies on disadvantageous of fixed force and command structures against hybrid threats.

(Photo: © Pıxabay)

Introduction

The question “Has the nature or character of warfare changed?” which was triggered by numerous developments throughout the history of warfare, has been keeping analysts and scholars busy for many years.

Hybrid warfare, methods of which have been used by both state and non-state actors in recent years, seems to have become the focal point of military planners at every level, primarily of security experts and defense planners. The recent increase in the literature on the subject in both military and civilian circles is another indication of this change of focus.

Clearly, robust change in the character of conflict and warfare of this magnitude brings with it strategic, conceptual and doctrinal changes. New forms of warfare motivate the emergence of new theories and concepts as well as triggering changes in the very character of strategy[1] (Gray, 2002).

This paper deliberately tries to avoid unnecessary conceptual questions such as “has the nature or character of warfare changed” or “is hybrid warfare something new or an echo of the past even a “déjà vu”?” Instead, the transformative effects of hybrid warfare on paradigms regarding providing security and stability, which were immensely effected by the recent developments such as; methods employed by the Russian Federation in Ukraine, terrorist organizations, ISIL’s tactics and techniques ranging from information warfare to savage killings of people, and PKK/PYD’s latest concept of urban warfare, namely “urban warfare supported from the field” that presents a hybridity of urban warfare and terrorist tactics. Furthermore, the reflection of these effects on the force and command structure of the armed forces will be examined and a new model will be proposed.

Hybrid Warfare from the Past to the Present

There is an ever increasing body of literature claiming that the most complex future threat “will utilize the synergy created by employing a variety of different warfare forms” (Mahnken & Maiolo (eds.), 2008). In other words, it can be claimed that the most able opponents of the future-including state-like structures or terrorist/radical groups-will aim to combine unconventional warfare and catastrophic forms of warfare. Therefore, there is an agreement among numerous analysts that future combat environment will be different from what we are used to: it will be multi-modelled and will involve multi variable. Recently, many scholars such as Hoffman have named this new phenomenon as “hybrid warfare” (Mahnken & Maiolo (eds.), 2008).

Looking at this new concept through the lens of the contemporary examples of conflict, such as methods employed by terror groups like ISIL and PKK or blurring warfare methods used by Russian Federation (RF) in Ukraine, that a new era is conflict in underway, in which variety of actors including states, non-state actors, state-like structures, terrorist groups, organized crime organizations, mobilized and armed people (tribes, ethnic, religious or ideological groups) are involved and the difference among various forms of combat such as conventional/non-conventional warfare, operations other than war, rebellions/public unrest which are precursor to civil war, and organized crime are blurred. This blurring has also made it quite difficult to distinguish between war-peace, combatant-noncombatant, and civilian-military (Schöfl, Rajaee & Muhr eds., 2008).

Scholars such as Habermayer (2011), Eaglen (2009), Owens (2008), and Kruzel (2009) who focused on counter measures against hybrid warfare claim that, in addition to employment of a variety of tactics and techniques (including rebellion and terrorism) and the introduction of new technologies simultaneously, the coexistence of simplicity and complexity, low and high intensity (conflict), soft and hard power have been the basic characteristic of hybrid warfare.

Various definitions of hybrid warfare converge on a particular point. The environment in which hybrid warfare is either used or emerged, have one common denominator: power vacuum. Prior to the RF intervention, there was no state authority in eastern Ukraine; ISIL has been exploiting the power vacuum in Syria, Iraq, Libya and even Afghanistan, and PKK/PYD has also taken advantage of the power vacuum in Syria while recently trying to create the perception that such a void is existent in some chosen areas in the eastern part of Turkey. Therefore, it is no surprise that hybrid warfare has flourished and will do so in “failed state” conditions (or try to create those conditions). In other words, the distinguishing feature of hybrid warfare is the utilization of a wide spectrum of warfare methods in order to create maximum synergy in a chaotic environment.

Another fact hybrid warfare revealed is the claim advocated by supporters of “the revolution in military affairs” that modern capabilities, such as precision attack, directed energy, high-tech ISR capabilities, artificial intelligence, and network centric capabilities will liquidate the enemy before giving him a chance to respond (Knox & Murray, 2000) This may not be always true in case of hybrid warfare. The shock experienced by the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) against Hizbollah in Lebanon (Murray & Mansoor, 2012) and the limited impact of the ongoing coalition operations against ISIL indicate that technological and conventional supremacy does not ensure clear-cut victory against an opponent using hybrid warfare tactics.

Through an analogical approach, claiming either state-based conflicts will go to the dustbin of history; or, with the rise of new regional and global actors a new era of conventional conflicts will begin is not much different than the discussions between Fukuyama and Huntington (End of History vs. Clash of Civilizations). This approach would enforce a choice between two extremes. With a similar analogical approach; discussions about hybrid warfare present a more balanced and rational choice in comparison to both “globalist” and “conflict based” approaches to global security. Such an approach would be more in sync with contemporary conflict experiences starting with Israel-Lebanon conflict. (One may also claim that, hybrid warfare based analyses could be extended to as far as antiquity). In fact, this approach is supported by numerous scholars from reputable institutions like Naval War College/U.S. and King’s College/UK (Boot, 2006; Owens, 2007; McCuen, 2008). On the other hand, some scholars still argue that hybrid warfare is not a new phenomenon, based on Clausewitz’ famous argument that “War is still war, even when its character changes”. According to Mansoor (2012), the roots of hybrid warfare can be traced back to the Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta, 5th century B.C. Ferris (2012) argues that British Empire’s combat experiences between 1700-1970 compels a wider approach claiming that during that time period the Empire faced 4 different types of enemies: Only conventional forces, a mixture of conventional and non-conventional forces, non-conventional forces refraining from guerrilla tactics, and guerilla forces.

However, Hoffman (2007) argues that they are all wrong, because they do not distinguish between “compound wars” in which conventional and non-conventional methods are used simultaneously (such as American Civil War, Arabic Rebellion against the Ottoman Empire, or Vietnam War) and “hybrid wars” involve much more complicated parameters and different actors than just a combination of conventional and non-conventional warfare. He also claims that hybrid threats can have a synergetic impact on both the psychological and physical dimensions (Hoffman, 2007).

Russian Hybrid Model in Eastern Ukraine.

(February 19, 2014. © Andrey Stenin / Sputnik)

To further clarify the subject, RF’s tactics and strategies in Eastern Ukraine will be examined as a recent example of hybrid warfare.

The indicators of Russian hybrid warfare methods in Eastern Ukraine can be traced back to RF 2010 Military Doctrine, which was amended in 2014. In that document, definitions are presented for “simultaneous use of military and non-military means, supporting military operations by diplomatic, economic, information and cyber means, synchronistic use of direct and indirect asymmetric measures”.

During the crisis, RF primarily made legal amendments in order to facilitate the annexation of Crimea and speed up the military decision making process (Reisinger & Golts, 2014; Pyung-Kyun, 2015) and then to shape the operational environment took particular steps such as:

Conducting strategic communication, propaganda and deception either by Putin personally or by other political/strategic level leaders [2] ,

In order to create confusion among western leaders and planners, releasing conflicting comments and acting in such manner on the field, and consistently pursuing a policy of “denial”[3] ,

After shaping the operational environment, national and international public opinion; Send combat units to border areas under guise of exercise, without necessary support elements in order to create a misconception that these units “cannot execute coordinated military operation” which enabled RF to deploy a sizable high readiness force which had the ability to intervene in 24-72 hours[4] (Reisinger & Golts, 2014), if needed, did not hesitate to play the nuclear card against NATO and the West [5]

While all attention was focused on abovementioned conventional units, managed to invade Crimea without shedding blood by using a web of operatives consisting of, Ukranian Private Security Companies that support the RF, local self-defense forces, Spetznatz units under disguise, Russian intelligence elements, and civilian para-military forces[6] (Reisinger & Golts, 2014).

In coordination with these military efforts, starting at pre-crisis period:

Developed a strategy to use soft power elements (social media, PR, CIMIC, perception management, STRATCOM, PSYOPS, energy card etc.) in sync with military means (Reisinger & Golts, 2014),

Organized Pro-Russian Ukrainian citizens and local politicians[7] ,

Conducted cyber-attacks against Ukrainian government buildings, communication, internet, transportation and energy infrastructure, hacked smart phones of government officials, even isolated Crimea from outside world by jamming radio and TV broadcasts just before the military operation (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015; Pyung-Kyun, 2015).

Enforcing the referendum outcome of which resulted in annexation demands, RF tried to give the impression that “civilian population decided with its own free will to side with RF” (Reisinger & Golts, 2014),

Due to Ukraine and Europe’s energy dependency on RF, did not hesitate to play the “energy card” at every opportunity (Popescu, 2014).

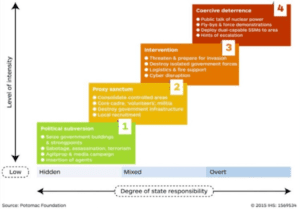

Figure 1 Russian Hybrid Model in Ukraine

(Source: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/key-features-kremlins-hybrid-war-shahriyar-gourgi

http://www.janes.com/article/49469/update-russia-s-hybrid-war-in-ukraine-is-working)

The tactics followed by RF during the crisis indicates that, soft and hard power elements are used in a mutually complimentary and supportive manner using hybrid warfare methods; and all efforts are camouflaged by professional propaganda and STRATCOM.

A closer look at RF’s hybrid methods reveals that RF has taken advantage of the sizable Western origin scholarly literature based on two Gulf War experiences at least as much as western counterparts. It can be inferred that, Russians studied the Iraq war quite thoroughly and applied the lessons–learned in Ukraine and Syria. While all Iraqi military apparatus is decimated within a timeframe of 3 weeks by far superior coalition forces; afterwards, in what can be considered as the second half of the battle defined by rebellion, terror and non-conventional warfare, the coalition failed to provide security and stability (The US Joint Force Command, 2001; Ricks, 2007).

Similarly, Russian planners seem to have been influenced by Hezbollah’s use of anti-tank, anti-ship missiles and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) as well as social media in addition to traditional guerrilla tactics against Israel (Matthews, 2008).

The Need for Supra-Joint Comprehensive approach (CA), Super Flexibility and Adaptability against Hybrid Threats

In generally agreed terms, CA is defined as a flexible combination of different approaches (USJFCOM, 2008); a multi-dimensional and cross-disciplinary reflex (Jarmyr, 2008); producing coordination between various military and political instruments as well as common objectives for different actors (Riemer & Muhr, 2011); a holistic management approach to integrate various dimensions of system, process and structure (Jarmyr, 2008).

This concept’s point of origin can be traced back to globalization discussions, which puts the future of the “state” into question in the classical sense, while trying to explain the concept of “the new war”. “Battlefields no longer belong solely to soldiers, but are inhabited by a variety of actors including media organizations, consultants, scholars, NGO’s, IO’s (UN, EU, NATO etc.), observers and volunteers” (Kaldor, 2012). Moreover we could estimate that security circles would witness increasing efforts concerning integration and communication among state and non-state actors in order to ensure national as well as international security and stability.

In addition to this estimation, we could also hold that in line with defense budget cuts and increasing importance of international law and norms, while the possibility of monoliteral acts to launch a war or conflict decreases, the need for coalitions or multinational forces increases (Kaldor, 2012).

Not surprisingly, the need for CA is high in contexts where cyber-hybrid-asymmetry dimensions are present, such as crisis management, stability operations, nation building, election security, and fight against global terrorist/radical/extremist groups, counter rebellion and organized crime (Riemer & Muhr, 2011). To be more specific, during and aftermath of a crisis or an operation, CA could have a bigger role in some specific situations especially where “the opponent has the freedom to choose from an array of different instruments”.

Another dilemma presented by operations in the future is balance between the need for specialists even in the most micro levels and the obligation to manage systems with an interdisciplinary and functional area based approach. Especially, crisis and operation management require preserving specialties during processes between functional areas (personnel, intelligence, operations, logistics, CIMIC etc.). Furthermore, starting from managing and fusing intelligence as well as directing appropriate specialties into decision making process by individuals or groups with interdisciplinary problem solving ability has become indispensable.

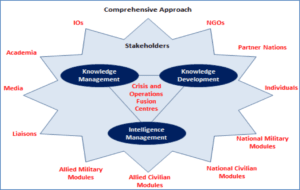

Moreover, in addition to the abovementioned dilemma, in order to sustain a coordinated CA, it will be necessary to achieve fusion and integration of not only national military and non-military capabilities, but also those of allied nations and for synchronization of hard and soft power elements (Figure 2).

Figure 2 CA Stakeholders (Author’s own product)

A Model for Hybrid Threats: New Modular Force Structure

Considering aforementioned factors regarding hybrid warfare, it should be noted that the hybrid threats in the operation environment necessitate a more flexible, adaptable, integrated, agile, and responsive force structure.

In search of a model for such a force structure, the “Modular Force Structure” concept comes into light. This concept has been around since 1990’s when the end of the cold war brought about very important modifications in the operational environment. However, the first official mention of this concept was in 2003 by US Army Chief of Staff Gen. Peter J. Schoomaer’s idea of “transforming the force from a forced base structure into a brigade based one”, which fueled a sizable amount of projects in the US army (Johnson, Peters, Kitchens & Martin, 2011). This idea is based on the consideration that post-cold war operational environment requires increased “flexibility and adaptability” and being able to deploy, sustain, operate and redeploy “the right function and capability, at the right amount, right place and right time” .

Both military and non-military organizations generally define “modularity” as the interoperability of independent and autonomous subsystems in a new configuration (Langlois, 2002). It is important to identify the difference between “modularity” and “task force”, i.e. “a group of force structured under a new command for a specific mission or missions” (Field Manual 101-5-1 & Marine Corps Reference Publication 5-2A). First of all, unlike “task force” approach, “modularity” considers bringing together “capabilities” rather than “units” and aims to optimize them towards mission objectives based on the required effect, duration of operation, cost-effectiveness and sustainability (Johnson, Peters, Kitchens & Martin, 2011). Another important distinction is the fact that modularity does not solely focus on combat readiness but also aims to increase responsiveness. During the force transformation studies, US Army aimed to be able to “deploy a high readiness brigade in 96 hours, a division in 120 hrs and five brigades in 30 days, anywhere in the world” (Rearrdon & Charlston, 2007). To that end, the search for a new unit which would be able to deploy faster than armored or mechanized brigades while being more lethal and sustainable than light infantry brigades resulted in “Stryker” brigades, which turned out to be the main element of the US Army’s transformation process (Green, 1999).

On the other hand, when “modularity” is considered in the light of flexibility requirements at the strategic and operational levels, there is a clear need for amalgamating the strategic level capability of “ability to change the configuration of the organization and to produce operational courses of actions” and operational level capability of “sustainability of a deployable force depending on the mission requirements and operational environment” (Soeters, Fenema & Beeres, 2010). To have that flexibility, first of all the “structure” needs to be identified, that is, which modules should be part of the structure and what functions should they perform. Afterwards, the modules need to become interoperable and “interfaces” to provide communication and synchronization be prepared to integrate different modules. In addition, “standards” based on which the performance will be evaluated should be identified (Soeters, Fenema & Beeres, 2010). Within this context, it becomes clear that operational flexibility would mean “achieving situational supremacy leaving the opponent with no choice”.

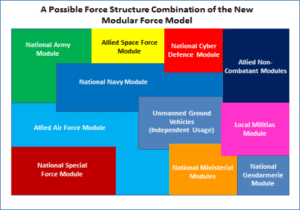

Following this brief summary of the concept of “modularity”, this paper will propose a new modular force model instead of classical modular force structure or constant force compositions which have proven to be disadvantageous in hybrid threat environments. In other words, to counter hybrid threats; “fixed structures and functionalities” vs. “the philosophy of modular design”. This new model which consists of expeditionary modules independent of geography, has a dynamic and flexible structure based on graduated readiness system. This model also aims to go beyond the US lead modular force structure understanding by combining all required capabilities –both national and/or allied, both military and/or civilian- in modules.

These “mission focused modules” are designed based on two main factors: First, each module would be the smallest component which has the expertise to conduct the same tasks regardless of operation type. Secondly, the ability to combine these modules with a surgical precision depends on the criteria such as mission requirements, desired end state and effects, properties of the operational environment, duration of operation, cost-effectiveness, sustainability etc. (Figure 3).

With these factors, necessary specialties will be utilized even at micro level and a flexibility against an enemy with “freedom to choose” in a chaotic operational environment will be achieved, but at the same time there will be an increased need for HQs and fusion centers based on CA, in order to ensure integration and interoperability of various modules with different functional areas. In other words, instead of a mosaic which consists of various modules, modules will need to be blended (amalgamated) by network centric capabilities.

Figure 3 A New Approach to Modular Force Structure (Author’s own product)

Limitations of the Study

Based on considerations discussed so far, in the following section, two hypotheses will be introduced. However, these hypotheses could not be tested because;

- There is not enough data to conduct those tests,

- Armed forces of different nations are reluctant to conduct field studies or share current available data on the subject.

By conducting field studies in the future and with armed forces’ increased willingness to share data, this study can be further expanded.

Regardless, this paper could be considered as a contribution to the literature on the subject and an initial step for further studies by providing a model built upon information from current literature and interpretations on the contemporary examples.

H1: There is a significant association between the dynamic Hybrid Operational Environment which consists of instable factors and actors, and increased need for CA and flexibility.

H2: In meeting the increased flexibility and adaptability required in the new chaotic operational environment, new modular force design model is more efficient than fixed force compositions.

Conclusion:

There is no doubt that marriage of globalization with hybrid threats is an extremely dangerous combination and that hybrid warfare thickens the Clausewitz’s “fog of war” (Howard & Paret, 1976). This combination and fog of war have undoubtedly provided the enemy who employs Hybrid Warfare with flexibility and ample opportunities to choose from a wide variety of options.

As mentioned by Kaldor (2012) in comparing the old and the new warfare, methods that were considered as solution or consequence in the old warfare context such as negotiation or agreement, victory or defeat, peace enforcing or peace keeping are questionable in the new warfare perspective. From this perspective, hybrid warfare, even though its novelty is debatable, can be classified as a new form of war because of the radical changes it dictates and it will surely keep professionals in defense and security area busy for a long time. It can be argued that a new era of hybrid warfare has begun in which the outcome can no longer be defined as “victory” or “defeat” and we will be facing longer lasting combats motivated increasingly by political, ideological, ethnic or religious factors. In terms of foreign intervention to battlefields, old methods like enforcing peace, peace keeping or stability operations will no longer be sufficient; benefits of globalization and technology are no longer exclusively exploited by nations but they are employed by non state actors such as state-like structures, terrorist organizations, proxies and independent individuals.

Moreover, against “the freedom of choice and flexibility” in a hybrid environment, rather than contingency plans, preventive strikes may need to be considered as more effective. Therefore, fixed force structures and classical HQ’s with compartmentalized sections from J1 to Jn will be futile. Instead, we need to prevent strategic shocks through crisis and operation management by newly designed strategic and operational HQs designed with a supra joint/combined CA approach, with advanced planning capabilities and with supporting information development and management as well as intelligence fusion centers. In conclusion, in order to defeat hybrid threats, we need a smooth but decisive transition from “fixed force composition and classical HQ structures” to “New philosophy of modular design” which will provide armed forces with flexible, agile, and responsive force compositions to conduct preventive strike, and HQs which are “super-flexible”, “super- adaptable” and “super-conductive” via enhanced network centric integration.

References

Boot, M. (2006). War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today, New York Random House, 472.

Clausewitz, C. Von (2007) On War, (Translated by M.D.Howard and P.Paret 1976), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.88.

Eaglen,M.M., (2009). Maintaining Full-Spectrum Capabilities in an Operating Environment of Hybrid Threats: The Army’s Future Requirements. Heritage Lecture, No.1134.

Ferris, J. (2012). Small Wars and Great Games. In Murray, W. & Mansoor, P.T. (eds.). Hybrid Warfare in History. p.199, Cambridge University Press.

Field Manual 101-5-1.

Gray, C. (2002). Strategy for Chaos. Revolutions in Military Affairs and the Evidence of History. London, Portlan, OR, p.94.

Green, W.A. (1999). Interim Strike Force HQ Digital LNO Nodes:Force Tailoring Enablers. Monograph, CGSC, p.2.

Habermayer, H. & Lang, P. Hybrid Threats and Possible Counter-Strategy. In Schöfl, J., Rajaee, B.M., Muhr, D. (eds.), Hybrid and Cyber War as Consequences of the Asymmetry, p. 249-250.

Hoffman, F.G. (2007). Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, p.8.

Jarmyr, F. (2008). Comprehensive Approach: Challenges and Opportunities in Complex Crisis Management. NUPI Report- Security in Practice No.11, Oslo: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

Johnson, Peters, Kitchens & Martin (2011). A Review of the Army’s Modular Force Structure. RAND Technical Report, pp.9-29.

Kaldor, M. (2012). New and Old Wars, Organized Violance in a Global Era. Stanford University Press.

Kofman, M. & Rojansky, M. (2015). A Closer Look at Russia’s “Hybrid War”. Kennan Cable, No.7, Wilson Center, p.2-3.

Knox, M. & Murray, W. (eds.), (2000). The Dynamics of Military Revolutions, 1300-2050. Cambridge.

Kruzel, J.J. (2009). US Must Prepare for Hybrid Warfare’, General Says. American Forces Press Servives, DC.

Langlois, R.N. (2002). Modularity in Technology and Organization. Journal of Economoic Behavior and Organization, 49, 19-37.

Mahnken, T.G. & Maiolo, J.A. (eds.), (2008). Hybrid Warfare and Challenges. Hoffman F.G, Strategic Studies, p.329-337.

Mansoor, Peter R. (2012). Hybrid Warfare: Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present. In Murray, W. & Mansoor, P.T. (eds.) Hybrid Warfare in History. p.1-3 Cambridge Press.

Marine Corps Reference 5-2A.

McCuen,J.J. (2008). Hybrid Wars. Military Review (April-May 2008), 107-113.

Matthews, M.M. (2008). We Were Caught Unprepared: The 2006 Hezbollah-Israeli War. Leavenworth, KS.

Murray, W. & Mansoor, P.T. (eds.), (2012). Hybrid Warfare, Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present. Cambridge, p.289.

Owens, M.T. (2008). America’s Long War. Ashland Uni.

Owens, M.T. (2007). Reflections on future War. Naval War College Review (Winter 2007).

Popescu, A.I.C. (2014). Observations Regarding the Actuality of the Hybrid War. Case Study: Ukraine. Strategic Impact No.4/2014, p.125-126.

Pyung-Kyun, W. (2015). The Russian Hybrid War in the Ukraine Crisis:Some Characteristics and Implications. The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 27(3), 383-400.

Reardon, M.J. & Charlston, J.A. (2007). From Transformation to Combat: The First Stryker Brigade at War. US Army Center of Military History, p.1-14.

Reisinger, H. & Golts, A. (2014). Russia’s Hybrid Warfare. Research Paper, NATO Defense College, No.105, p.3,8.

Ricks, T. (2007). Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq, 2003 to 2005. New York.

Riemer, A. & Muhr, D. (2011). Take off your Sunglasses: Hybridity and Cyber Warfare-Driving Moments for Asymmetric Warfare. In Schöfl, J., Rajaee, B.M., Muhr, D. (eds.), Hybrid and Cyber War as Consequences of the Asymmetry, p.85.

Schöfl, J., Rajaee, B.M., Muhr, D. (eds.), (2011). Hybrid and Cyber War as Consequences of the Asymmetry. p.288.

Soeters, J., Fenema, P. & Beeres, R. (2010). Managing Military Organizations, Theory and Practice. Cass Military Studies, p.73-74.

The United States Joint Forces Command’s (USJFCOM), (2008). Multinational Experiment 5, Key Elements of a Comprehensive Approach: A Compendium of Solutions.

The US Joint Force Command (2001). A Concept for Rapid, Decisive Operations. J9 Joint Futures Lab.

[1] “Strategy is a permanent nature, but an ever-changing character” C.Gray (2002).

[2] See Putin: Nazi virus vaccine losing effect in Europe, 15 October 2014, http://rt.com/politics/official-word/196284-ukraine-putin-nazi-europe

[3] See http://eng.kremlin.ru.news/6763

[4] Working meeting with defense minister Sergey Shoigu, 2 July 2014, http://eng.kremlin.ru/news/22590

[5] Russia to fully renew nuclear forces by 2020, 22 September 2014, http://rt.com./politics/189604-russia-nuclear-2020-mistral/.

[6] See Alberto Riva, Why Putin’s use of unmarked troops did not violate the Geneva Convention, International Business Times, 05 March 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/alberto-riva-putin-did-not-violate-geneva-convention-2014-3.

[7] See Tom Balmforth, Russia mulls special day to recognize its polite people, 04 October 2014, http://www.rferl.org/content/russia-ukraine-cremia-little-green-men-polite-people/26620327.html., Direct line with Vladimir Putin, 17 April 2014, http://eng.kremlin.ru.news/7034, and http://www.vesti.ru/videos?vid=onair, NATO would respond militarily to Crimea-syle infiltration: general, 17.08.2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2041/08/17/us-ukraine-crisis-breedlove-idUSK-BN0GH0JF20140817