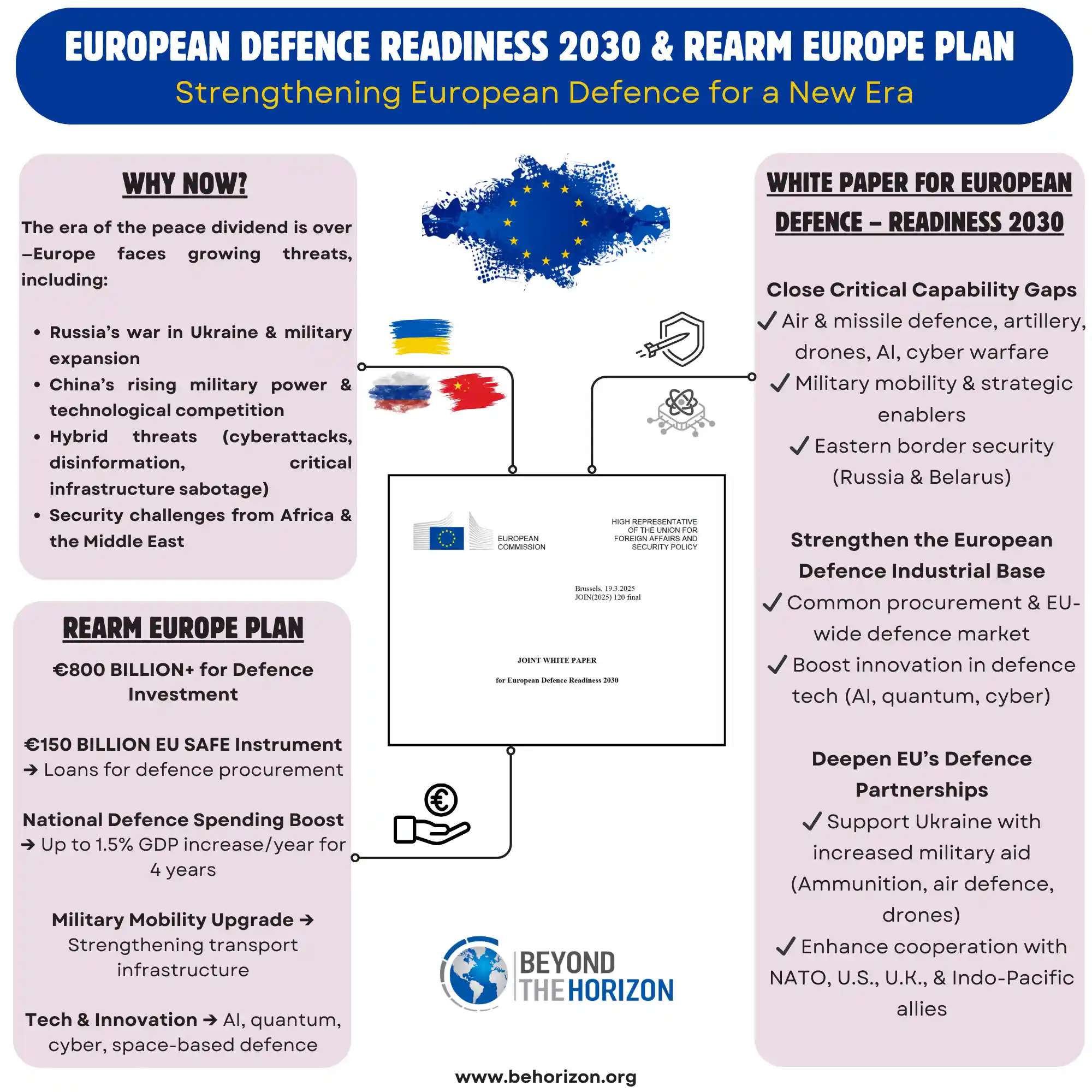

ReArm Europe – Scaling Investment for Credible Deterrence

The EU aims to massively boost defense spending and cooperation to build a credible deterrent by 2030.

- Recommendations:

- Launch €150B SAFE loan program for joint EU arms procurement.

- Ease EU budget rules to unlock ~€800B for defense over 4 years.

- Promote joint planning and reduce duplication across 27 militaries.

- Challenges:

- Securing political consensus on shared procurement.

- Converting high-level ambition into signed contracts and delivered systems.

Industrial Ramp-Up & Strategic Stockpiles – From Plans to Production

Europe must rebuild its defense industrial base to support sustained high-intensity conflict and reduce external dependencies.

- Recommendations:

- Implement “Ammunition Plan 2.0” to build strategic reserves.

- Push for at least 65% EU-origin procurement to strengthen internal supply chains.

- Clarify ESG rules and expand European Investment Bank (EIB) support for defense.

- Challenges:

- Fragmented industry and reliance on U.S. systems.

- Investor hesitation and regulatory obstacles.

- Shortages in skilled labor and critical components.

Military Mobility – Bridging the Infrastructure Gap

Rapid force deployment across EU territory is vital for credible deterrence.

- Recommendations:

- Upgrade roads, rail, ports, and airfields via EU-wide planning.

- Harmonize border and customs procedures for troop movement.

- Enhance coordination with NATO and non-EU allies (e.g., UK, Norway).

- Challenges:

- Technical and bureaucratic hurdles slow military movement.

- Risk of underinvestment in less-visible mobility upgrades.

Ukraine – The Immediate Test of European Defence

Supporting Ukraine is framed as Europe’s most urgent defense task and a proving ground for strategic autonomy.

- Recommendations:

- Deliver 2M+ artillery shells/year and scale arms transfers.

- Deepen integration of Ukraine into the EU defense ecosystem.

- Support and co-invest in Ukraine’s defense industry.

- Challenges:

- Avoiding donor fatigue and maintaining public support.

- Balancing Ukraine aid with Europe’s own rearmament needs.

Strategic Autonomy & Transatlantic Cooperation – Not Either/Or

Europe seeks to act independently when necessary while strengthening NATO and U.S. ties.

- Recommendations:

- Focus on capability-building (e.g., air defense, refueling, space).

- Align industrial policies without excluding key partners (e.g., UK, U.S.).

- Maintain transparency and coordination with NATO.

- Challenges:

- Diverging national visions (e.g., France vs. Poland/Baltics).

- U.S. concerns over “Buy European” policies.

- Potential exclusion of non-EU allies like Türkiye without clear mechanisms.

Implementation & Criticisms – Turning Vision into Action

The strategy is bold but hinges on fast, coordinated implementation and overcoming entrenched inefficiencies.

- Recommendations:

- Fast-track SAFE loans, procurement programs, and fiscal flexibility by 2025.

- Prioritize mature, scalable projects and expand defense workforce.

- Regularly review progress via EU Defense Summits.

- Challenges:

- Bureaucratic inertia, fragmented priorities, and defense-industrial lag.

- Economic headwinds and shifting political winds.

- Long lead times for new capabilities vs. short political cycles.

Conclusion – A Blueprint Worth the Execution

The 2030 vision is ambitious but achievable with sustained effort. Supporting Ukraine, strengthening industry, and reinforcing NATO complement each other. Strategic autonomy is not about separation — it’s about resilience.

Introduction: A Turning Point for European Defence

Europe’s security landscape has fundamentally changed. Russia’s war against Ukraine brought high-intensity conflict back to the continent, shattering assumptions that peace could be taken for granted. After decades of defense under-investment, European nations face urgent pressure to rebuild credible military strength. As a joint EU White Paper on European Defence Readiness 2030 notes, Europe must undertake a “once-in-a-generation” surge in defence investment to deter those who threaten its security. The United States, while remaining Europe’s key ally, has signaled it “believes it is over-committed in Europe and needs to rebalance” toward other regions. In other words, Washington expects Europeans to shoulder more of their own defense. In response, EU leaders have unveiled the Readiness 2030 strategy – informally dubbed the “ReArm Europe” plan– aimed at boosting Europe’s capabilities, industry, and strategic autonomy by the end of this decade. This analysis examines the plan’s key proposals and their implications for a more secure and self-reliant Europe, blending strategic, industrial, and geopolitical perspectives.

ReArm Europe: Investing in Credible Deterrence by 2030

At the heart of the Readiness 2030 report is an ambitious drive to massively increase European defense spending and cooperation. The plan calls for a sustained investment surge to remedy critical capability shortfalls and build a credible deterrent against threats like Russia. European defense budgets have in fact been rising since 2022 – total EU military spending in 2024 hit an unprecedented level (over €100 billion, nearly double 2021 levels) – yet Europe still spends far less on defense than the U.S., and even lagged behind Russia in recent years. The ReArm Europe initiative seeks to close this gap. As EU’s High Representative Kaja Kallas put it, “Russia’s economy is in full war mode… the EU needs a long-term plan to arm Ukraine [and itself] to avoid future attacks”. In practical terms, the Commission’s plan has several pillars:

- EU Defense Loans (SAFE instrument): Up to €150 billion in EU-backed loans would finance member states’ joint procurement of arms within Europe. This “Security and Action for Europe” (SAFE) facility incentivizes countries to buy equipment together from European suppliers – only allowing non-EU suppliers (like U.S. or UK firms) if their governments sign agreements on security of supply. The goal is to keep more of Europe’s defense spending within Europe, boosting the continent’s own industry.

- Easing Fiscal Constraints: Recognizing that rigid budget rules have discouraged military spending, the plan urges a coordinated activation of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact escape clause for defense. This could let countries exceed normal deficit limits by an amount equal to new defense outlays – potentially unlocking an additional 1.5% of GDP (up to €800 billion over four years) for defense across Europe. In short, EU capitals would get license to spend big on defense without breaching EU budget rules, reflecting a new political priority on security.

- Joint Procurement and Planning: The Commission is prepared to act as a central purchasing coordinator (via the European Defence Agency or new mechanisms) if requested. The White Paper argues that collaborative procurement is the most efficient way for Europe to acquire both large quantities of “consumables” (like ammunition and missiles) and complex high-tech systems. By aggregating demand, nations can achieve economies of scale, lower per-unit costs, and ensure interoperability from the outset. The plan even floats the concept of “Defence Projects of Common European Interest”, akin to major joint industrial projects, to develop critical capabilities like air defense systems with EU support. If implemented, these measures could reduce wasteful duplication among 27 national militaries and direct Europe’s newfound defense euros into more coordinated programs.

Crucially, this spending and procurement push is framed not as an alternative to NATO, but as a contribution to it. Stronger European capabilities will “increase our contribution to Trans-Atlantic security” by 2030. In areas from tanks to air defense, European NATO members meeting their capability targets will ultimately bolster the Alliance. The difference is that Europe aims to develop more of those capabilities itself, achieving a degree of strategic autonomy while remaining embedded in the transatlantic alliance. EU officials stress that the new level of ambition “is higher than 2%” of GDP for defense spending – going beyond NATO’s longstanding 2% benchmark. This signals European willingness to carry a larger share of the burden and to build a deterrent force credible enough to stand on its own if necessary. As Andrius Kubilius, the EU’s first-ever Defence Commissioner, bluntly stated: “450 million EU citizens should not have to depend on 340 million Americans to defend ourselves.” The success of ReArm Europe will hinge on whether member states now follow through – turning the White Paper’s prescriptions into contracts, factories, and deployments.

Industrial Ramp-Up and Strategic Stockpiles: Europe’s Arsenal Imperative

European leaders have come to recognize that military credibility depends not just on budgets, but on the capacity to produce and deploy equipment at scale. The war in Ukraine exposed glaring shortfalls in Europe’s defense industrial base – especially in the availability of ammunition, missiles, and spare parts for a sustained high-intensity conflict. Early in 2023, the EU pledged an “Ammunition Plan” to deliver 1 million artillery shells to Ukraine within a year, only to find that less than half that number had actually been delivered by the deadline. This shortfall underscored how Europe’s stockpiles and production lines, diminished after decades of peacetime downsizing, were unprepared for the brutal consumption rates of modern war. The Readiness 2030 report directly addresses this, calling for “Ammunition Plan 2.0 – effectively, the creation of strategic stockpiles of ammo, missiles, and components coupled with expanded industrial capacity for timely replenishment.

The plan envisions Europe developing sufficient reserves of key munitions so it can sustain intense fighting if ever required (whether by supporting a partner like Ukraine or defending itself). Achieving this means rapidly scaling up production. Indeed, Kubilius identified “massive production of what [Europe] already makes, such as conventional ammunition” as the first of three priority areas to tackle. Across Europe, governments are now funding factories and supply chains to boost output of everything from 155mm shells to shoulder-launched missiles. For example, in early 2025 Finland announced a new €200 million TNT factory to fix a critical bottleneck in explosives for ammunition, a project deemed of “major importance” for Europe’s ability to produce ammo and support Ukraine long-term. Such investments address the upstream inputs (like propellants and explosives) needed to sustain higher weapons production.

Beyond raw capacity, the EU is moving to fix structural weaknesses in its defense-industrial ecosystem. A recent expert review (the Draghi Report) found that Europe’s defense manufacturing remains highly fragmented, with nearly 80% of procurement spending going outside the EU (primarily to U.S. suppliers). This external reliance is unsustainable if Europe seeks industrial resilience. The White Paper’s proposals to “buy European” and create an EU-wide defense equipment market aim to reverse that trend. Under the plan, member states will be urged (and incentivized) to source at least 65% of their defense purchases from European (or associated) suppliers. Common procurement financed by the SAFE loans will require partnering with EU/EFTA countries or Ukraine. This should channel demand to European industry, encouraging expansion of production lines. It also implicitly pressures European firms to improve their offerings to meet urgent needs at competitive prices, otherwise governments might still opt for imports. Notably, countries can still buy non-European kit if it clearly outperforms or is faster/cheaper – an important flexibility for allies like Poland or the Netherlands that are purchasing U.S. systems such as HIMARS rockets or F-35 jets. But the overall thrust is clear: Europe intends to reduce its security dependency on the U.S. by manufacturing more at home, harnessing its single market to build a robust European Defence Technological and Industrial Base.

Another industrial challenge is financing and investment. European defense firms – especially smaller subcontractors – often struggle to raise capital due to stringent regulations and investor concerns. As analysts have noted, many European banks hesitate to fund defense projects due to reputational and environmental, social, governance (ESG) policies, leaving defense SMEs significantly under-served by private capital. The EU’s plan tackles this head-on. The European Investment Bank (EIB) will double its defense-related investments to €2 billion per year and loosen criteria to support projects like drones, space, cyber and military infrastructure. Furthermore, the Commission is clarifying that sustainable finance rules do not prevent investing in defense, to dispel the notion that arms manufacturing is incompatible with ESG frameworks. By mobilizing private capital – the fifth pillar of ReArm Europe – the EU hopes to unlock the vast resources of Europe’s financial sector for defense innovation and expansion. If successful, this could attract “hundreds of billions” in additional investment per year into defense and high-tech security fields, vastly increasing industrial resilience. Removing financial roadblocks will be key to achieving the necessary “industrial ramp-up that Europe needs.”

Of course, ramping up production is only half the battle – the output must actually reach the arsenals. Here, collaborative procurement and pre-stockpiling play a role. The EU’s approach of jointly purchasing large volumes of munitions can help build buffers against future crises. It’s telling that Europe is now aiming to supply Ukraine with at least 2 million artillery shells per year going forward – more than double the earlier pledge – while simultaneously refilling its own depots. This dual use of increased production is a delicate balancing act. The experience of the past two years revealed how slowly Europe’s fragmented procurement processes can move; the White Paper stresses speeding them up and using the “EU toolbox” to coordinate orders for efficiency. If Europe succeeds in establishing sizeable, strategic stockpiles – especially of ammunition, fuel, and spare parts – it would greatly enhance credible deterrence. An adversary would know that Europe could fight at high intensity for an extended period without running dry, a powerful disincentive to aggression.

Military Mobility: Moving Forces Where They’re Needed, When They’re Needed

Even the best-equipped forces are of limited use if they cannot rapidly deploy to the frontlines. That’s why military mobility is highlighted in the EU Readiness 2030 agenda as a critical enabler for European defense. In a conflict, NATO must be able to swiftly move troops and heavy equipment across Europe’s internal borders – whether to reinforce an exposed Baltic flank or to project stability abroad. Yet practical obstacles abound: bureaucratic border procedures, rail gauge mismatches, weight limits on bridges, and insufficient transport assets can all slow deployment. After 2014, NATO and the EU began addressing these issues, but progress was modest. Now, the war next door has imparted new urgency to building an “EU-wide network” of transport corridors, upgraded infrastructure, and streamlined procedures for military mobility.

The European Defence Readiness report defines military mobility as a seamless network of land, air, and sea routes and support services enabling fast transport of troops and gear across the EU and partner countries. The inclusion of partner countries is notable – it underscores cooperation with non-EU NATO allies (like the UK, Türkiye and Norway). In fact, EU leaders explicitly encourage boosting security ties with NATO countries such as Britain, Canada, and Norway in parallel to EU efforts. Projects to expand railway capacity, widen roads, and increase port and airfield throughput for heavy military cargo are being co-funded through EU mechanisms (like the Connecting Europe Facility). Additionally, simplifying cross-border customs and regulations for military convoys is a priority. During recent NATO exercises, commanders observed that diplomatic clearances and legal hurdles can significantly delay movement – something the EU can help harmonize among its member states.

Improved mobility is essential for credible deterrence. Potential aggressors must believe that Europe can rapidly reinforceany threatened point. NATO’s new force posture calls for tens of thousands of troops at high readiness, ready to rush to an ally’s aid within days. Europe’s contribution to that depends on eliminating logistical chokepoints at home. The Readiness 2030 plan accordingly flags “military mobility” as one of the critical areas for investment (alongside air defense, drones, etc.). Some of the simpler, urgent mobility upgrades could even be among the first projects financed by the new SAFE loans , given their straightforward utility. For example, reinforcing key bridges in Eastern Europe to support 70-ton tanks or expanding warehouses for pre-positioned equipment would yield immediate readiness benefits. Indeed, the U.S. has pre-positioned heavy equipment in Europe for decades; now the EU is looking to do the same for European forces. Joint mobility planning is another aspect – NATO and the EU are sharing data on infrastructure and coordinating exercises like Defender Europe, which practice large-scale deployments across the continent.

By 2030, if the proposals are followed, Europe should have far better integrated transport infrastructure for defense. This means a tank or brigade in Germany could be loaded on a train and arrive in the Baltics or Romania much faster than today, or an EU Battlegroup could deploy to a crisis in days rather than weeks. Military mobility is a prime example of EU-NATO cooperation yielding tangible results – NATO defines the requirements, and the EU helps deliver the means. As such, it’s a cornerstone of both European strategic autonomy and transatlantic solidarity. No single nation could overhaul the continent’s transport network alone; collective action through the EU amplifies everyone’s security. The challenge will be maintaining momentum for what are often unglamorous infrastructure projects once headlines move on. But the lessons of 2022-24 are clear that logistics win wars – or prevent them by enabling robust forward defense.

Ukraine: The Frontline of European Defence

From a European perspective, supporting Ukraine is not just an act of solidarity; it is the “immediate and most pressing task for European defence,” as the Readiness 2030 report states. EU leaders describe Ukraine as “the frontline of European defence”, where the outcome will shape Europe’s own security for decades. The report’s proposals reflect a resolve to sustain Ukraine’s war effort and integrate Ukraine into Europe’s defense architecture. In practical terms, this means ramping up deliveries of weapons and ammunition, training Ukrainian forces, and even investing in Ukraine’s defense industry so it can better supply itself. The stakes are high: a Ukrainian victory or stalemate that preserves its sovereignty will severely weaken Russia’s military and deter future aggression, whereas a Ukrainian collapse would embolden Moscow and directly threaten European nations.

Accordingly, the EU’s new strategy calls for massive ongoing support to Ukraine. The targets are ambitious: at least 2 million artillery shells per year provided to Kyiv along with more air defense systems, anti-missile missiles, and drones. For context, Ukraine has been firing thousands of shells daily to hold back Russian forces, and its NATO partners struggled to keep pace in 2023. Now, Europe is attempting to scale its collective production and procurement to meet Ukraine’s needs at a war tempo. This will involve not only European factories working overtime but also creative arrangements like joint purchases from third countries’ stockpiles. Indeed, reports indicate the EU has sought ammo from global suppliers to fill immediate shortages. Such efforts, while bridging short-term gaps, reinforce the message: Europe is determined to “continue the flow of arms and ammunition to Kyiv” while also strengthening its own defenses.

In addition to arms deliveries, training and capacity-building for Ukraine form a key part of the plan. The EU and member states have already trained tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers, and that will continue annually. This not only helps Ukraine on the battlefield now, but also aligns Ukraine’s military more closely with Western standards – effectively preparing it for future membership in Western structures. The inclusion of Ukraine as a potential participant in EU joint procurement is symbolically and practically significant. It integrates Ukraine into Europe’s defense supply chain, allowing Kyiv to benefit from economies of scale and giving its industry access to a larger market. In fact, the EU is starting to funnel more financial support directly to Ukraine’s defense industry to boost its self-sufficiency. A stronger Ukrainian defense sector can help arm its forces now and provide Europe with another trusted supplier for the future.

Strategically, unwavering support for Ukraine is central to Europe’s claim of taking charge of its security. It demonstrates to allies and adversaries alike that Europeans are willing to “fend for themselves and [for] Ukraine” if needed. The U.S. has borne the lion’s share of military aid to Ukraine so far, but American domestic politics could shift – as hinted by U.S. signals that Europe must be prepared to carry on even if Washington’s focus turns elsewhere. Europe is thus working to ensure that even if transatlantic politics change, Ukraine will not be abandoned. This is a real-world test of European strategic autonomy: can the EU and its members collectively provide the necessary deterrent support in their own neighborhood? The Readiness 2030 blueprint suggests cautious optimism – if its industrial ramp-up succeeds, Europe will have both the materiel and financial mechanisms to keep Ukraine in the fight. Yet there are critics. Some worry about “Ukraine fatigue” among European publics, or question whether certain countries will remain as generous if the war drags on. EU officials counter that supporting Ukraine is investing in Europe’s own security. Every Russian tank destroyed in Donbas is one less that could threaten NATO territory. In sum, helping Ukraine win is not just a moral imperative but a strategic one for Europe: it buys time for Europe’s rearmament, depletes the forces of its primary adversary, and upholds the principle that might does not make right in Europe.

Strategic Autonomy and Transatlantic Cooperation: Complementary, Not Contradictory

A recurring theme in the European Defence Readiness 2030 report is “strategic autonomy” – Europe’s ability to act independently to defend its interests. But European strategic autonomy is envisaged alongside a strong NATO and transatlantic bond, not in opposition to it. This balance is evident in the report’s language and the broader policy discussion. The document frankly acknowledges the United States’ pivot: Washington’s attention is increasingly drawn to Asia and its own borders, meaning Europe “can no longer take for granted” the old security architecture. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it plainly: “We must buy more European… [to] strengthen the [European] defense industrial base” because the status quo reliance on U.S. suppliers leaves Europe vulnerable. This drive for more autonomous European capabilities has sometimes raised concerns about decoupling from the U.S. or duplicating NATO. However, EU leaders insist that a more capable Europe will “benefit transatlantic security and help EU members of the Alliance reach their NATO targets more quickly”. In other words, a Europe that can stand on its own feet militarily will be a stronger ally to the U.S., not a weaker one.

One concrete example is air and missile defense. After witnessing Russia’s barrages on Ukrainian cities, Europeans know they need better defenses against missiles and drones. The EU is encouraging a joint European approach to air defense – potentially via a “European Sky Shield” initiative – to plug gaps not covered by NATO’s integrated system. If Europe invests in modern SAM batteries and radar networks now, it eases pressure on U.S. assets to cover Europe in a crisis. Similarly, Europe’s push for “strategic enablers” like air-to-air refueling tankers, heavy airlift planes, space-based intelligence, and secure comms directly complements NATO capabilities. These enablers are expensive, so relatively few countries have them; by teaming up, Europeans can contribute more to Alliance operations. A joint EU satellite constellation or a fleet of European aerial refuelers by 2030 would reduce the current over-reliance on U.S. enablers for deployments. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has consistently welcomed EU defense efforts as long as they remain inclusive and complementary. The EU’s White Paper itself calls the UK an “essential European ally” and talks of increasing security cooperation with Britain – a clear signal that EU defense initiatives will not shut out key NATO partners. In fact, negotiations are underway for a formal EU-UK security pact by 2025, which would further align European efforts.

Transatlantic burden-sharing is another way to view strategic autonomy. For years, U.S. administrations have nudged Europe to spend and do more for defense. Now Europe is stepping up – not to appease Washington, but out of self-interest given the threats at hand. This should ultimately rebalance the alliance in a healthier way. By 2030, if EU nations hit the “higher than 2%” spending ambition and develop key capabilities, the U.S. will be able to focus more on Asia without worrying that Europe is undefended. From an American perspective, a Europe capable of deterring Russia largely by itself is a boon; from a European perspective, that capability is the essence of autonomy. The challenge is ensuring political cohesion such that Europe’s and America’s visions of deterrence remain aligned. So far, Russia’s aggression has unified NATO and EU like never before – evidenced by the historic EU-NATO joint declarations and unprecedented coordination on sanctions, military aid, and intelligence sharing. EU defense initiatives like the European Defence Fund or PESCO projects were once viewed skeptically in Washington; today there is greater recognition that these can fill niches NATO doesn’t address. The AP succinctly noted that EU nations are encouraged to boost ties with NATO allies worldwide even as they build autonomy. This reflects a mature approach: Europe’s security isn’t isolationist – it relies on a network of alliances and partnerships, with NATO as the bedrock.

However, differing views within Europe must be managed. Not all EU members interpret “strategic autonomy” the same way. France has championed it as a goal of being able to act alone if needed, while countries on NATO’s eastern flank (Poland, Baltic states) stress that autonomy should never mean weakening the U.S. security link. These views are being reconciled by focusing on practical capability outcomes. For instance, France’s call to “buy European” collided with Poland’s preference for U.S. equipment, but the EU plan accommodates both by offering incentives for European buys without an outright ban on non-EU arms. Over time, if European industries produce high-quality systems (like the French-led SAMPT missile defense or Germany’s next-gen tank project) that meet eastern countries’ needs, the reliance on U.S. kit may diminish organically. Likewise, France has come around to the reality that NATO (and the U.S. nuclear umbrella) remains indispensable for deterrence against Russia; thus French support for EU defense now emphasizes complementarity with NATO. The EU-NATO cooperation has reached new heights since 2022, with regular coordination cells and the inclusion of NATO allies in EU defense projects. This synergy will need to continue so that Europe’s autonomous capability development also strengthens NATO’s collective defense. If done right, Europe in 2030 will have both the independent means to respond to crises in its neighborhood and be a reliable first responder within NATO, with the U.S. acting as a backstop or “rear echelon” power for Europe rather than the frontline defender.

Implementation Challenges and Criticisms

The vision laid out in the European Defence Readiness 2030 report is bold – but can it be realized? Skeptics point to a familiar hurdle: Europe’s difficulty in translating grand defense plans into action. One challenge is political will and unity. The initial panic from Russia’s invasion spurred many EU countries to announce defense increases, but sustaining that momentum as the war drags on and economic pressures mount is hard. Some parliaments have been slow to actually spend the new funds; for example, Germany’s procurement bureaucracy has moved sluggishly in placing orders, raising doubts about how quickly even available money turns into equipment on the ground. The EU’s answer – providing loans and loosening fiscal strictures – addresses the budget side, but not the bureaucratic inertia and fragmentation that often delay European defense projects. As the Niinistö Report highlighted, lack of cooperation among member states has led to redundant programs and higher costs. Overcoming this means convincing nations to cede some control and buy off-the-shelf jointly, rather than each supporting their own national champion industries for every platform. The White Paper’s emphasis on joint procurement is spot on, but implementation may face inertia from domestic industrial lobbies or mistrust between countries. The success of initiatives like the joint EU ammunition procurement in 2023 will need to be replicated for missiles, artillery systems, and more – a tall order, but not impossible as urgency is a great motivator.

Another criticism is whether the European defense industry can actually scale up in time. Companies can’t magically double output overnight; they need long-term orders and clarity to invest in new production lines. The EU is trying to provide exactly that through the coordinated spending push, but industry insiders note other bottlenecks: skilled labor shortages, supply chain dependence on foreign suppliers, and regulatory hurdles. The ESG and banking issues mentioned earlier illustrate how European policies outside the defense realm can inadvertently hamstring defense production. If environmental rules make it extraordinarily costly to run steel plants or chemical facilities, defense manufacturing will suffer. Balancing green goals with the urgent need to expand arms production is a real dilemma for Europe; the plan to adjust EIB criteria and clarify sustainable finance rules is a step in the right direction. But national regulations also need to adapt – for example, allowing factories to run 24/7 and fast-tracking permits for expansions. France and Germany have begun to relax some peacetime constraints on arms makers, acknowledging the “war economy” need. Europe’s highly developed civilian industries could also be leveraged, but that requires contingency planning now, not in the middle of a crisis.

There are also strategic questions. Is 2030 a realistic timeline for achieving the desired defense posture? Five years is a short horizon in defense planning – major equipment programs often take a decade or more from design to delivery. The EU’s list of capability gaps (air defense, drones, cyber, etc.) will not be fully closed by 2030, especially if new development is needed. However, Europe can make significant gains by then if it focuses on mature solutions and interoperability. For instance, purchasing additional Patriot or IRIS-T air defense units that are already in production, or expanding proven drone fleets, could be done by late this decade. But next-generation systems (like the FCAS fighter jet or MGCS tank) won’t arrive until the 2030s – they are beyond this timeline. So Europe will need to achieve deterrence in 2030 largely with upgraded versions of current platforms and through better readiness and quantity. This raises the issue of readiness and training. European armed forces, even if better equipped, must be ready to deploy on short notice. That implies high readiness levels, ample stockpiles, and robust command structures. NATO is adjusting its command structure and plans to account for larger European forces. The EU’s role here is more limited, but the EU could facilitate things like mutual recognition of military certifications, easier movement of troops, and coordinated exercises. If political disputes or lack of coordination impede these, the effect of new hardware could be blunted.

A potential criticism comes from outside observers who fear the EU’s defense push might sideline NATO or provoke U.S. displeasure. The “buy European” element has prompted concerns about protectionism – U.S. officials have at times warned against closing markets, given that European and American defense industries are deeply intertwined. The EU’s compromise, excluding non-EU firms from its loan program unless agreements are in place, may still rankle some allies (the UK and U.S. notably). Over time, however, if Europe demonstrates it can fulfill its capability needs internally, transatlantic squabbles over contracts may subside. Another concern is whether countries like Türkiye or others outside the EU will be alienated. Türkiye, a NATO member, is excluded from the EU programs unless a special deal is struck. This could complicate EU-NATO cohesion if not managed, though Türkiye’s own strategic choices have distanced it somewhat from European defense integration. The key will be maintaining transparency and cooperation through NATO to ensure no duplicative planning. For example, if the EU launches a new drone program, it should coordinate with NATO’s Alliance Ground Surveillance program to avoid overlap. Thus far, EU officials like Kallas and Kubilius have been careful to stress complementarity, and NATO’s leadership has been involved in consultations.

Finally, domestic political change could jeopardize elements of the plan. A change in government in a major country might slow the defense buildup or resist EU-level coordination. The fact that 19 out of 27 EU countries recently wrote to support more EIB funding for defense indicates broad consensus now, but public opinion must remain supportive. Managing public expectations – that increased defense spending is necessary insurance, not an offensive militarization – is crucial. European citizens generally rallied in support of Ukraine and see the need to strengthen defense, but if economic conditions worsen, some may question high military outlays. Policymakers will have to clearly communicate the security benefits and ensure that visible improvements materialize to justify the costs.

Conclusion

The European Defence Readiness 2030 report outlines a comprehensive vision of a Europe that can defend itself and contribute more meaningfully to global security. Achieving this vision by the end of the decade will require extraordinary effort and focus. The roadmap is there: surge investment, streamline procurement, pool resources, rebuild industries, and reinforce partnerships. Now, Europe’s institutions and capitals must turn these plans into concrete outcomes. In the immediate term, that means adopting the proposed measures in EU forums and funding them – for example, passing the SAFE EU defense loan facility into law, enacting the coordinated fiscal escape clause for defense, and kicking off the first joint procurement projects under this framework within 2025. Member states need to present their national defence investment plans and identify common projects without delay. A special European Council meeting in March 2025 has already pinpointed priority capabilities; by mid-2025, countries should agree on a small number of flagship collaborative programs – be it a European air defense shield, a main battle tank project, or a pan-European ammo stockpile initiative – and commit politically to seeing them through. These early wins would build momentum and confidence in the ReArm Europe plan.

Equally urgent is to keep scaling support for Ukraine. In many ways, Ukraine’s fight is buying Europe time to rearm. European leaders must ensure steady deliveries (the 1 million rounds per year, now 2 million, and other arms) continue, and that financing for Ukraine’s government and military is secured for 2024, 2025, and beyond. Pledges should be multi-year to provide certainty. As Ukraine hopefully advances toward a just end to the war, Europe should prepare for the post-war integration of Ukraine into its security structures – potentially fast-tracking Ukraine’s accession to the EU and deepening NATO ties. By 2030, Ukraine could even be part of the EU and a formal ally, which would cement the frontline of European defense far to the east and dramatically expand Europe’s strategic depth and manpower. Planning for this scenario – including rebuilding Ukraine’s forces to NATO-interoperable standards with European help – is a “next step” once active hostilities subside.

On the industrial front, the next months should see defense companies across Europe receiving large orders as part of the EU’s coordinated push. Monitoring and expediting these contracts will be important. The Commission and EDA can help by troubleshooting supply chain issues – for instance, coordinating raw material stockpiling (rare earths, explosives) at the European level to avoid bottlenecks. The idea of strategic reserves could extend beyond ammunition to components and energy relevant for defense. Additionally, Europe must nurture innovation even as it focuses on existing capabilities. The White Paper mentions supporting research in emerging tech (AI, quantum, etc.). The EU’s Defence Fund and other R&D programs should be funded and expanded if possible, so that by 2030 Europe isn’t just catching up, but breaking new ground in defense tech. Collaboration with the private tech sector and cross-border innovation hubs can accelerate this.

One cannot overlook the human factor: Europe needs well-trained personnel to wield its new capabilities. Many militaries face recruitment shortfalls. As part of the readiness drive, governments might consider policies to attract and retain talent in the armed forces – better pay, joint training programs, and modern facilities. A goal for 2030 could be that Europe not only has more equipment, but enough troops at high readiness to use it effectively, with a culture of readiness. NATO’s forthcoming force model requires a substantial increase in European forces on standby; meeting that will require personnel growth or reallocation in several countries.

Lastly, sustaining political consensus will be key. Each year from now to 2030, progress will need to be reviewed – possibly at regular EU Defense Summits. If a particular initiative stalls, leaders should course-correct quickly. Civil society and expert communities can help keep up pressure by highlighting successes or lapses. The debate about European strategic autonomy has shifted from “whether” to “how fast.” In this sense, Russia’s aggression served as a brutal catalyst that ended complacency. The forward-looking question is whether Europe can seize this momentum to truly transform its defense posture. If it does, by 2030 the EU will have gone from a security consumer to a security provider: able to deter aggression credibly, manage crises in its neighborhood, and back up its values with hard power when necessary. The transatlantic alliance will be stronger for it, as a more resilient and self-reliant Europe can act in partnership with the U.S. rather than in dependence.

In conclusion, Europe’s strategic autonomy by 2030 will not mean solitude – it will mean strength. Strength to defend the peace within Europe and contribute to stability beyond. To get there, the blueprint of the European Defence Readiness 2030 must be relentlessly implemented. The coming years will test Europe’s capacity for unity and action. But if the commitments made on paper are honored in practice, Europe is on the path to a defense posture that is fit for purpose in a more dangerous world – a Europe that is ready, by 2030, to uphold its own security and help shoulder the transatlantic burden of safeguarding democracy.

Related Infographics