“Only God can be omnipotent (all-powerful) without danger because His wisdom and justice are always equal to His power.So, there is no power on earth in itself so worthy of respect or vested with such a sacred right that I would wish to let it act without control and dominate without obstacles” (Tocqueville 1969: 252).

Democracy is a revolutionary system because it regularizes the relationship between power and the community’s needs. If rulers establish this equilibrium, the people are provided with a secure and peaceful atmosphere in which to live. People have the freedom to choose in democratic societies. Educated and confident citizens elect representatives in the hopes that they will protect democratic values and encourage stability and peace. It is at this point that democracy’s drift can be observed. It is difficult for rulers to govern healthy individuals. Some prefer anti-democratic ways of governing, keeping their people frightened and hopeless. Controlling pessimistic people and giving them orders is easy for despots.

However, despots prefer to be seen as democrats. They use the label of democracy to remain popular and obscure their anti-democratic practices. Today, the leaders of Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Pakistan, and many other nations use the word “democracy” to define their governing methods. However, the definition of democracy does not change according to the ruler. If you silence the media, defraud democratic elections, block all kinds of opposition, and undermine the law, your system cannot be labeled a democracy. Perhaps such rulers can control pessimistic and hopeless people for a while, but the unavoidable end awaits, as it did for despots in the past.

This is why the philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville continues to be important today. His warnings about and solutions to despotic attempts at ruling democracies shine a light on the dangerous tendencies of certain governing practices. His concept of “democratic despotism” was born from his comparative analysis of the United States (U.S.) and Europe. As a nobleman, he had the direct experience and intellectual capacity necessary to properly evaluate the effects of the revolution occuring in Europe. His journey to the U.S. in the 1830’s allowed him to devleop his theories on and fully understand the applicability of democracy.

This is why the philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville continues to be important today. His warnings about and solutions to despotic attempts at ruling democracies shine a light on the dangerous tendencies of certain governing practices. His concept of “democratic despotism” was born from his comparative analysis of the United States (U.S.) and Europe. As a nobleman, he had the direct experience and intellectual capacity necessary to properly evaluate the effects of the revolution occuring in Europe. His journey to the U.S. in the 1830’s allowed him to devleop his theories on and fully understand the applicability of democracy.

This study clarifies the concept of democratic despotism through an analysis of Tocqueville’s observations and a discussion of their impact on international security and stability. To achieve this, I first consider Tocqueville’s understanding of liberty, equality, and democracy. Second, I describe Tocqueville’s warnings regarding the path to despotism in new democracies. Then, I discuss his solutions and the various alternatives available for avoiding dangerous democratic tendencies. Finally, I analyze the impact of his thoughts on today’s international security and atmosphere of stability.

1.Tocqueville’s Understanding of Liberty, Equality, and Democracy

Tocqueville believed that genuine liberty could be achieved by way of subjection to authority. He did not consider liberty to be “the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority and pursuing self-pleasure.” According to him, this form of liberty was evil and belonged only to animals. He generally related liberty to decentralisation, participation, and local self-governance, and used these concepts when evaluating various nations’ democratic experiences.

Tocqueville understood equality as a social and political idea. He aruged that equality progresses slowly, and this progress cannot be controlled by humans (1969: 12). He explained that the French Revolution was designed to stand against royalty and provincial institutions. The character of the revolution was, therefore, both republican and central. Thus, equality and tyranny would be concepts in opposition to one another. Conversely, he observed the events unfolding in the U.S. and found applicable examples of equality in American associations, their understanding of individualism, and the participatory nature of the citizens. On the basis of this comparative analysis, he felt that the conditions of democracy and equality in a society are important to understanding its democratic tendencies.

When Tocqueville used the word “democracy,” he was referencing both the political form of the government and the resulting social state (Tocqueville 1990: 4). He believed that democracy was inevitable and efforts to stop it amounted to a fight against God (1969: 12). The reason why he found it to be inevitable was likely based on his experience of the French government’s unsuccessful attempts to establish democracy. As a result, he felt that contemporary democracies were moving in the wrong direction and the U.S. was the only accomplished example.

The reasons why he believed democracy to be safe in the U.S. can be explained via a number of institutional, organisational, and individual factors. The township (as a local self-governing administration, and thus a factor of decentralisation), freedom of political association, an independent judiciary, freedom of the press, and religion (he believed in the positive role of churches) all supported the preservation of liberty and democracy in the U.S. Although it was unlikely that in every society these factors would serve as a cure for or safeguard against dangerous governing tendencies, they did assist in wrestling with the main problems often seen in democracies. According to Tocqueville, these threats to democracy include an excessive drive for equality, individualism, materialism, a preponderance of legislative power, and the abuse of one’s love for freedom. Democratic despotism was often the result of these dangerous democracy-based tendencies.

2.Dangerous Tendencies in New Democracies

Tocqueville’s observations and analysis of revolutionary thought offer a basis for understanding the political and social changes occurring in society. The reason why democratic revolutions in Tocqueville’s time were so violent was because the intellectuals who drove them had no prior experience with the topic, and the peasants they were trying to protect had been so critically brutalised. When a revolution begins, expectations are high. However, reality is almost always different from the ideal. Thus, a gap exists between expectations and reality. In Tocqueville’s time, the outcome was the nobility losing their power. They cut themselves off from the middle class and peasantry. When the regime passed to democracy, new and dangerous tendencies emerged that were different from the ideals that drove the movement. These included an excessive drive for equality, individualism, materialism, a preponderance of legislative power, centralisation, direct election of representatives, and an excessive love for equality.

Tocqueville believed that an excessive drive for equality had an evil effect on democracy. He stated that the desire for equality was too strong in democratic countries, and this passion often led to despotic rule; he felt that absolute equality was the true enemy of democracy (1969: 57). Tocqueville considered individualism to have democratic roots, and it was this phenomenon that gave rise to equality (1969: 507); this was based in people’s interests. Individuals tend to focus on themselves, avoiding the societal bonds and duties that link people together and force them to realize their dependence on one another. If citizens are too individualistic, despotism becomes a dangerous possibility because individualists can either choose to fulfil their civic duties or exercise their freedom.

For Tocqueville, excessive equality also led to materialism and selfish individualism in the bourgeoisie. The dangers of materialism are derived from the desire for equality because people believe that they deserve as much wealth as they can acquire. Materialism also stems from the philosophical tendencies fostered by democracies, the scorning noble ideas and thoughts of immortality. Materialism allows people to become so interested in their personal pursuit of wealth that they neglect to use their political freedom. They may even give up their freedom intentionally in exchange for a “good” despotism that provides them with material prosperity.

The preponderance of legislative power was considered yet another threat to new democracies. The legislature is the most direct representative of the will of the people, and democracies tend to give it the most power of all the governmental branches. Yet if there are insufficient checks on this power, it can easily become tyrannical. Tocqueville wrote that liberty is in danger when this power encounters no obstacle that can check its course and give it time to moderate itself (1969: 252). He asserted that democracy leads to centralisation and that this tendency is one of the worst in newly democratic societies. He believed “that there are no nations more at risk of falling under the yoke of centralised administration than those whose social state is democratic” (1990: 152). According to Tocqueville, it is democratic governments that arrive most rapidly at administrative centralisation, losing their political liberty.

A related constitutional issue that Tocqueville identified was the weakening of the independence of the executive branch, and therefore an increase in the power of the legislature. The president must be re-elected, and if he hopes to accomplish this, he loses much of his ability to make independent decisions based on his judgment. Instead, he must bow to the whims of the people, and constantly try to make them happy even though they may not have the knowledge necessary to properly judge what is best for the country as a whole. Indirectly, therefore, allowing the President to run for re-election increases the danger of the tyranny of the majority. A related problem is the direct election of representatives and short duration of their time in office. These provisions result in the selection of a mediocre body of representatives and the prevention of their acting according to their best judgment, since they must constantly defer to public opinion.

Tocqueville believed that these dangerous democratic tendencies could be controlled, even in the midst of despotism. Institutional and non-institutional factors that Tocqueville regarded as preservers of liberty included the township (a mark of local self-governence and decentralisation), freedom of political association, an independent judiciary, freedom of the press, and the presence of religion (in a positive role) in the U.S.

3. Precautions for Avoiding Dangerous Democratic Tendencies

The Township (Administrative Decentralisation)

Tocqueville stated that: “without local institutions a nation may give itself a free government, but it has not got the spirit of liberty.” Though he recognised that administrative centralisations would greatly increase the efficiency and uniformity of the government, he admired the decentralised American system because it allowed the people to exercise their freedom. He argued that local liberties were much more important than political rights in deciding the general affairs of an entire country, because a person “has little understanding of the way in which the fate of the state can influence his own lot” (1969: 511). Minor questions of local interest have an obvious visible effect on everyday life. As a result, people are much more effectively drawn together and more likely to exercise their liberty if they are given control of minor local affairs. Importantly, “free institutions and the political rights enjoyed there provide a thousand continual reminders to every citizen that he lives in society” (1969: 512).

However, the problem with this argument is that his distinction between governmental and administrative centralisation was weak and never particularly effective (1990: 171). Tocqueville himself knew this and stated:

The permanent tendency of [nations whose social state is democratic] is to concentrate all governmental power in the hands of a single power that directly represents the people, because, beyond the people, nothing more is seen except equal individuals merged into a common mass. Now, when the same power is already vested with all the attributes of government, it is highly difficult for it not to try to get into the details of administration … and it hardly ever fails eventually to find the opportunity to do so. We have witnessed it among ourselves (1990: 162-163).

Therefore, the two centralisations were actually inseparable; when an instrument or branch of government claiming to represent the people has sufficient power, it cannot resist the temptation to apply it more widely and in more precise ways.

Independent Judiciary System

Constitutionally speaking, to Tocqueville the independent judiciary, with the power of judicial review, was extremely important because it could proclaim certain laws unconstitutional. In the U.S, the Supreme Court provides practically the only check on the tyranny of the majority. Judges are appointed, not elected, and they serve life terms, giving them a great deal of independence to make the decisions that they believe are best without needing to worry excessively about public opinion. A related beneficial institution in the American system is the jury. While juries may not always be the best means of attaining justice, they serve a very positive political function, forcing citizens to think about other people’s affairs and educating them in the use of their freedom.

Tocqueville thought that the jury system was highly beneficial to the political sphere, because it could serve as a powerful tool for public education, particularly in teaching people how to use their freedom responsibly, a lesson crucial to the wellbeing of a democracy. For this reason, Tocqueville believed that the jury system was “one of the most effective means of popular education at society’s disposal” (1969: 275). Decentralisation and an independent judiciary systems serve as institutional preservers of liberty, while non-institutional factors include freedom of the press, the right of association, and most importantly to Tocquevill, religion.

Freedom of the Press

Tocqueville asserted that freedom of the press could serve as a means of keeping liberty alive and foiling the tyranny of the majority. It is an institution that helps to maintain democracy by keeping people informed of politics, encouraging political activity, and motivating them to exercise their freedom. Moreover, the free press circumvents the tyranny of the majority by influencing the masses. The decentralisation of the press, as is the case in the United States, has the opposite effect of all-encompassing unification that can lead to the tyranny of the majority.

The Right of Association

According to Tocqueville, dangerous democratic tendencies and democratic precautions such as the freedom of association struggle against one another. Free association can be an excellent tool for combating individualism and allowing people to exercise their freedom by taking part in politics. People gain contact with one another via their associations. They share and spread their political thoughts through this contact. The press assists them in spreading these messages to the public. However, in some situations and political atmospheres, this can be dangerous. Tocqueville argued that “the omnipotence of the majority seems to me such a danger to the American republics that the dangerous expedient used to curb it is actually something good” (1969: 92).

Religion

Tocqueville believed that religion could correct many of the prominent flaws of democracy, such as individualism, materialism, a lack of stability, and the tendency to misuse or undervalue liberty. The separation of church and state helps religion to maintain and even increase its influence in society. According to Tocqueville, religion is much more than another type of association; it is highly beneficial, both politically and socially. Religion teaches people how to properly use their freedom. Since the government provides no absolute standards, it is necessary that religion offer moral bounaries. He stated:

Despotism may be able to do without faith, but freedom cannot. Religion is much more needed in the republic they advocate than in the monarchy they attack, and in democratic republics most of all. How could a society escape destruction if, when political ties are relaxed, moral ties are not tightened? And what can be done with a people master of itself if it is not subject to God? (1990: 294).

Religion brings people together in a community of common belief, so it combats against individualism.

Furthermore, religion is practically the only means of counteracting the materialistic tendencies of democratic peoples. Religion turns people’s minds beyond the physical, material aspects of life, and directs them to the immortal and eternal. Similarly, Tocqueville asserted that America had not yet fallen into this tyranny of the majority, not because of its governmental institutions or laws, but due to its mores (1990: 253). He explained that:

religion regards civil liberty as a noble exercise of men’s faculties, the world of politics being a sphere intended by the Creator for the free play of intelligence. Religion, being free and powerful within its own sphere and content with the position reserved for it, realizes that its sway is all better established because it relies only on its own powers and rules men’s hearts without external support. Freedom sees religion as the companion of its struggles and triumphs, the cradle of its infancy, and the divine source of its rights. Religion is considered as the guardian of mores, and mores are regarded as the guarantee of the laws and pledge for the maintenance of freedom itself (1969: 47).

In the example of America, he argued that religion fought against the dangerous tendencies of a democratic regime by turning people’s minds beyond the physical, material aspects of life, to the immortal and eternal. He defined religion as similar to what was seen in the Middle Ages.

However, Tocqueville also recognized that American religion was not like the religion of that bygone era. It was a secularized version more concerned with worldly welfare than any sort of reward or punishment in an afterlife:

Not only do the Americans practice their religion out of self-interest, but they often even place in this world the interest which they have in practicing it. Priests in the middle ages spoke of nothing but the other life; they hardly took any trouble to prove that a sincere Christian might be happy here below. But preachers in America are continually coming down to earth. Indeed, they find it difficult to take their eyes off it. The better to touch their hearers, they are forever pointing out how religious beliefs favor freedom and public order, and it is often difficult to be sure when listening to them whether the main object of religion is to procure eternal felicity in the next world or prosperity in this (1969: 530).

4. Discussion of Continuing Applicability of Democratic Despotism

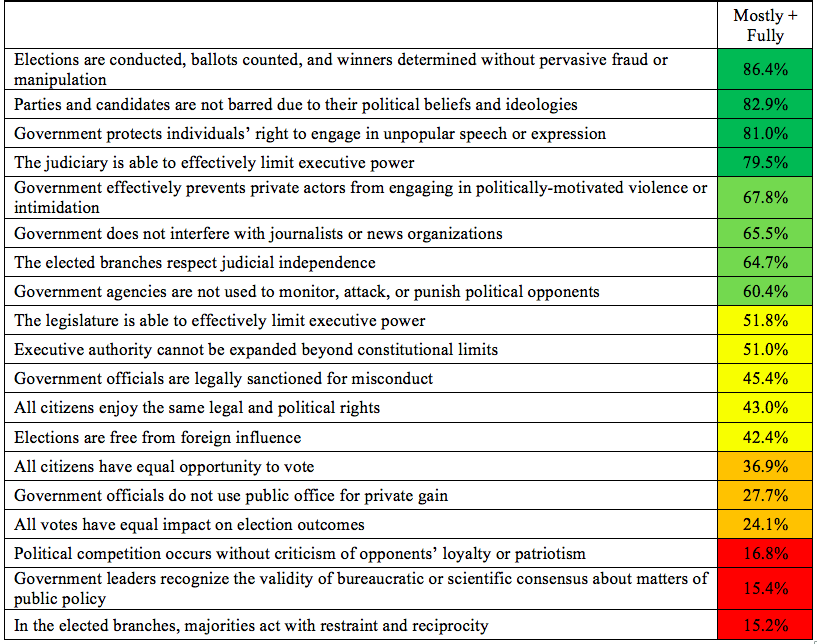

Democratic despotism is hazardous. It is not related to a single ruler, but rather with rule by the majority. As Tocqueville argued, such a democracy is common and can slowly degrade people. Therefore, people living in such a society may not understand its tendency towards this type of end. One can see the continuing applicability of democratic despotism in modern democracies today. There is still this dangerous tendency around the world, including in today’s America (see Table 1) and France. The struggle among the various elements of democracy is ongoing.

Table 1: 2017 U.S. Democracy Survey

Democracy in the United States is strong, but showing some cracks. That is the conclusion of a new survey of 1,571 political scientists. Despotic rulers and governments continue to undermine individual freedoms. More than 65 million people around the world have been forced from their homes, and citizens regularly face anti-democratic practices such as political violence, repression, censorship, and human rights violations in despotic countries. Tocqueville’s main solution, that “governments should not be the only active powers,” can serve as a remedy for both national and international peace and stability. Yet what if despots repress the independent judiciary, and eliminate freedom of press and the opportunity for civil associations? There is no easy answer. However, a powerful international response and support for all democratic civil endeavors would be a good start.

Cihan Aydıner is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Louisiana State University

References:

Alexis de Tocqueville. Democracy in America. Translated by George Lawrence, edited by J.P. Mayer. Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Alexis de Tocqueville. Democracy in America. Edited by Eduardo Nolla, translated from the French by James T. Schleifer. Liberty Fund. Paris, 1990.

BrightLineWatch U.S. Democracy Survey – February 2017.