Turkey is one of the few countries conducting air defence almost solely with aircraft, despite sizable armed forces with a wide array of capabilities. As odd as it sounds, it has been a disturbing reality for military officials for a long time as the Armed Forces continues to operate obsolete air defence systems like Nike, Hawk and Rapier. However, air defence has not been the only problem. Due to increasing threat of Ballistic Missile (BM) proliferation especially after the First Gulf War, Iran’s nuclear program and Syrian Civil War, Turkey’s concerns have peaked. Therefore, defence planners started considering missile defence aspects of possible Surface to Air Missile (SAM) system procurement as well.

Never ending story has begun with seeking for co-production of Arrow system with Israel in 1997 however, it was objected by US due to concern that the Arrow interceptor is a Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)[1] Category 1 item. But later, in 2001, US agreed to an arrangement with Israel and Turkey for the co-production of a system similar to the MTCR Category 2 Patriot, but Turkey cancelled the negotiations after the financial crisis.[2]

The next saga started in April 2007 when the Undersecretariat for Defence Industries (SSM) issued a request for information to evaluate the price and availability of the systems in the context of Turkish Air Force Long-Range Air-and Missile-Defence System (T-LORAMIDS) project. After the tender process, 3-Billion € contract was clinched with China Precision Machinery Import and Export Corporation (CPMIEC) for its HQ-9 [exported as FD-2000] that included co-production[3] solutions in 2013.[4]

On 15 November 2015 (just before the G-20 summit in Antalya, Turkey) however, Turkey decided to abandon the current project and develop its own national missile defence system with the use of its domestic resources, which meant that the whole ordeal lasting 10 years was mostly a waste of time.

Nevertheless, Ankara-Moscow rapprochement following shooting down of Russian jet and increased relations after the coup attempt on the 15 July 2016, gave birth to a possibility of making a deal with Russia. In early 2017, Erdogan stated that Turkey now prefers the S-400 due to considerable price reduction from the 2013 offer[5].

Photo: Yevgeniy Yerokhin, http://www.missiles.ru/foto_606zrp-2010.htm

Indeed, S-400 is one of the most sophisticated SAM systems currently in the market and when you think about the recognition and reputation of Russian SAM systems, it might sound like a wise decision. Yet, there are lots of different considerations, not only strategic but also techno-military, that need to be taken into account before making such a strategic decision.

Before finding an answer to whether S-400 is the right choice, one needs to make a quick threat assessment for Turkey. When we look at the geographical position and the historical rivalries, one can say that Russia (including Armenia), Greece (Including Greek Cypriots), Syria and Iran are most likely countries, which Turkey may have a confrontation with. On the Russian front, from a military strategy planning perspective, enormous number of Russian BMs cannot possibly countered with any plausible Turkish inventory in the future. This challenge is also valid for NATO, but in any case, Turkey depends on other defensive measures (e.g. NATO alliance, diplomacy, passive defence etc.) to have an acceptable level of protection. A long lasting conflict with Greece is highly unlikely due to assured catastrophe to both sides and almost certain intervention from US and Europe. Therefore, Turkish strategic planners would naturally need to concentrate on threat from Syria and Iran.

Both Syria and Iran have BM capability. When compared to Iran, Syria’s BM inventory consists of shorter range and older technology missiles, which puts Iran as the main BM threat to Turkey, and also to the West. According to current reliable open sources, Iran currently, has capability to strike 2000 -2500 km range with her Shahab 3 and Sejjil BMs and is pursuing development of longer range BMs.[6] In addition to robust Medium-Range Ballistic Missile (MRBM) inventory, Iran has numerous Short-Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBM). Despite being a smaller threat than Iran, Syrian threat by no means should be overlooked. Even though Syria had used a sizable portion of SRBM inventory during the internal conflict, she still has the capability to threaten Turkey.

While making a threat assessment, assessment of opponent’s intention is critical. Currently, Turkey has a very tense relationship with Syria, but a relatively stable relationship with Iran dating back a long time in the sense of armed conflict. Nevertheless, an everlasting sectarian divide between Sunni and Shia will not allow a true peace and mutual trust between these regional powers. As a result, it can clearly be stated that Turkey does not have the luxury to underestimate BM threat from neighbours.

So, is S-400 the correct solution then? According to open sources, S-400 is capable of intercepting Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBM) as well as strategic cruise missiles such as Tomahawk.[7] S-400 is able to launch four different types of missiles and only two types of them can be used against BMs. It’s not clear yet which type or types of missiles Turkey would like to buy. The newest 400 km range 40N6 type missile and 200/250 km range 48N6E2/E3 type missiles are capable of intercepting BMs. [8] Although open source BM ranges vary, it is safe to say that US equivalent of S-400 should be THAAD. However, some argue that the 40N6 missile has similar characteristics with the US latest version of sea-based Standard Missile 3 (SM-3) Block IA-IB.[9] One thing is certain that like many other Russian SAM systems, S-400 has never been tested in real combat. Furthermore, there is scarce information about its test launches against BMs. Therefore, one cannot help to be a little suspicious regarding IRBM intercept claims.

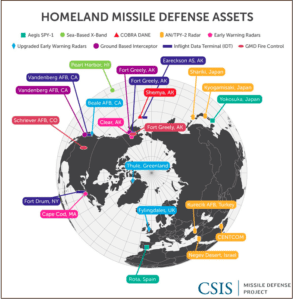

As most of the experts agree that the success of missile defence rests with early detection and sensor fusion as well as interceptor capability. US as the most capable nation in missile defence, has numerous different types of sensors around the world for global missile defence (See picture[10]). And all those sensors are connected to the center in Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado through (C2BMC[11]) system. Say, there is a launch from Iran coming towards Europe. The first sensor to detect this launch would be Satellite systems with their IR sensors. Then, AN/TPY-2 X-band radar in Turkey or Israel will track the missile and pass this information to the other sensors and interceptors like Aegis SM-3. With their SPY-1 radar, Aegis systems will detect early enough to calculate firing solution, which maximizes the footprint of the weapon system.

As it can be seen in this example, different kinds of sensors are connected to each other, which increases  the intercept probability dramatically. For an ideal missile defence following are crucial; Early Warning & Detection, Precision Tracking, Interceptor Capability and Integration. Of course, these are important aspects of just the ‘Active Defence’ pillar of the US BMD doctrine. BMC3I[12], Counter Force and Passive Defence are the others.[13] NATO BMD mission adopted a similar approach as well.

the intercept probability dramatically. For an ideal missile defence following are crucial; Early Warning & Detection, Precision Tracking, Interceptor Capability and Integration. Of course, these are important aspects of just the ‘Active Defence’ pillar of the US BMD doctrine. BMC3I[12], Counter Force and Passive Defence are the others.[13] NATO BMD mission adopted a similar approach as well.

A closer look at the NATO BMD system would reveal that, it comprises of sensors, interceptors and C2 systems. And all of those systems are connected with a Link 16 network, which is connected to BMD Operations Center in HQ AIRCOM, Ramstein, Germany via US C2BMC system.[14] From NATO perspective, S-400 system will have no chance of being integrated into NATO BMD system and Turkish Defence Minister already stated that the system will not be integrated to NATO and will operate independently.[15] As a result, Turkey will not be able to take advantage of the European Phased Adaptive Approach’s (EPAA) sensor network. When one considers the short time of flight of the BMs, it is crucial to detect early enough. Turkish officials have disputed this assertion, saying that because the system will use the domestically produced Herikks/Skywatcher system, S-400 operators will have access to all of NATO’s early warning assets[16]. But this reasoning carries a grave twisting of the facts. While missile operators may be able to see the complete air picture with heritage systems, the system will not have access to the combat management software that cues the missile defence interceptors and there will be no automatic data transfer.

So, how effective will the system be without integration? As explained earlier, the most important feature of today’s modern weapon systems is their ability to work together. The performance of the system is maximized through the intertwining of various sensor, weapon and command elements. Platforms and sensors stationed on land, sea and air have to function in joint command control by using the situational awareness of each other. These systems should be capable of transferring data instantaneously via the tactical data links, passing through the most remote locations.

That’s why NATO has developed the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defence System (NATINAMDS). It integrates a network of interconnected national and NATO systems comprised of sensors, command and control facilities and weapons systems. NATINAMDS detects, tracks, identifies and monitors airborne objects (e.g aircraft, helicopters, unmanned aerial vehicles and ballistic missiles), and – if necessary – intercepts them with surface-based or airborne weapon systems.[17] Additionally, NATO is pursuing Air Command and Control System (ACCS) project in order to integrate air and missile defence systems by increasing their effectiveness and provide robust command and control (C2) for a long time. [18]At the core of this large C2 project, is the ability of the weapon systems and sensors to communicate with each other, to transfer data, namely, integrate with each other.

Even though this article focuses on military aspects, there is an undeniably large political dimension of this possible procurement. It seems that politicians are sacrificing military opinions and expectations by underestimating the importance of having an effective air and missile defence. Of course, Turkey is free to choose any system, however, not only being a NATO member but also considering the recent US urge to other NATO nations to invest more in the defence systems, it would be very disappointing decision to procure a system that will not serve Alliance’s collective defence principle.

If Turkey had not been a NATO member and nearly all of her arsenal had not depended on West, the debate would have been very different. But currently, buying a sophisticated Russian system will be a dramatic strategic shift and may mean future Russian system procurements in other areas. Nevertheless, Turkey is notorious for unstable diplomacy and international relationships recently. Buying such a complex system will make Turkey heavily dependent on Russia for training & education, technical expertise and spare parts, which then, requires a stable and reliable bilateral relationship. Russian–Turkish relations have always been problematic from a historical perspective. Therefore, a possible conflict may result in serious repercussions in due course. Turkey does not have the luxury to risk billions of euros for political moves by procuring a system that cannot be used to its full effectiveness. From the political perspective, an investment to an opponent’s defence industry will certainly not be welcomed by allied nations, as Russia is again being considered a threat to NATO after invasion of Crimea and her intervention to civil war in Ukraine by hybrid strategies. No matter how you spin it, it will be very hard to explain NATO allies the rationale behind buying a Russian system especially in current security conjecture, let alone the technical aspects regarding the inability to use the advanced radar data from the NATO BMD mission (TPY-2 radar in Kurecik). Will Turkey go through with this purchase, and if it does would she be regarded as the dependable, committed ally she once was? Or will this be remembered as another chapter in the long and painful T-LORAMIDS story?

[1] MTCR is an informal group of 34 states (Turkey is a member) that have agreed to adopt national export control policies that incorporate a common export control list. Controlled items are divided into two categories. Countries are expected to apply the greatest restraint to the export of Category 1 items, which include rockets, missiles, and drones that can fly more than 300 kilometers while carrying a 500 kg payload. Category 2 items may be capable of flying more than 300 km, but only when carrying light payloads.

[2] https://turkeywonk.wordpress.com/2013/10/11/turkeys-missile-defence-decision-ankara-will-miss-nato-cueing-capabilities/

[3] Co-production and technology transfer were important requirements for Turkish authorities

[4] http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/t-loramids.htm

[5] http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/03/turkey-russia-ankara-tests-nato.html

[6] https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/iran/

[7] http://www.deagel.com/Artillery-Systems/S-400_a000371001.aspx

[8] http://www.ausairpower.net/APA-S-400-Triumf.html

[9] https://www.rt.com/news/239961-near-space-missile-defense/

[10] https://twitter.com/Missile_Defense/status/857675952708628481 CSIS Missile Defense

[11] Command and Control, Battle Management, and Communications (C2BMC)

[12] Battle Management, Command, Control, Communications And Intelligence

[13] http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/32aamdc.htm

[14] http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_07/20160711_160709-bmd-def-architecture.pdf

[15] https://sputniknews.com/military/201703161051638728-ankara-s-400-integration-nato-defense-system/

[16] https://turkeywonk.wordpress.com/2013/10/11/turkeys-missile-defense-decision-ankara-will-miss-nato-cueing-capabilities/