POLICY PAPER

THE CURRENT PRACTICE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION CONCERNING THE CONTINENTAL SHELF, EEZS, AND FREEDOM OF INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION IN COASTAL AREAS (BALTIC SEA, ARCTIC, FAR EAST, CASPIAN SEA, BLACK SEA). ITS CONTRADICTIONS WITH NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES AND THE EXPECTED STEPS IN THE BLACK AND AZOV SEAS

The maritime policy of the Russian Federation (RF) includes several hundred years of historical experience of advancing the interests of the empire, and subsequently a global state, on the sea. Today, Moscow successfully combines in its maritime policy all possible instruments and means of economic, legal, scientific, technical, and military influence. Its main strategy – the establishment of a parity from the US maritime influence of the RF – remains unchanged. On the way to this goal, Moscow demonstrates exceptional tactical maneuverability, embodying the expansionary maritime practices of the United States from contemporary maritime legal realities from the last century. At the same time, restrictions imposed on Russian marine aspirations within the modern system of maritime law are regarded by Russia as temporary, namely, the RF sees maritime law sees as an unfinished and imperfect matter that can and should be changed, creating a new political reality. The asymmetric nature of relations between Ukraine and the RF and Moscow’s objectives in the Black Sea basin allow it to utilize the whole of its experience in this area. An understanding of the instruments and practices of the RF in other maritime regimes and its relations with neighboring countries is important for the development of maritime policy of Ukraine, which is an integral part in protecting Ukrainian interests from the attacks of the RF.

Official documents of the RF consolidate the primacy of international law (the UN Convention on International Maritime Law (UNCLOS, 1994 and conciliation protocols thereto, 1994-1997) in maritime policy of Russia. Among such documents the most significant are:

- The Marine Doctrine of the Russian Federation for the period until (2001)

- Decree by the President of the Russian Federation. 20 July 2017 №327. “Approval of the Fundamentals of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the field of naval operations for the period until 2030” (2017)

- The concept of foreign policy of the Russian Federation (2016)

- National security strategy of the Russian Federation until 2020 (2009) and national security strategy of the Russian Federation (2015)

- Military doctrine of the Russian Federation (2014)

Russia’s actions in the maritime spaces show that the most precise Russian maritime policy (interests, goals, and objectives) is described in the provisions of the Decree of the President of Russia №327 “on approval of the fundamentals of State policy of the Russian Federation in the sphere of military-maritime For the period until 2030.” The modern maritime policy of Russia is strategically focused not only on ensuring the implementation of sovereign rights of the RF in the waters belonging to it under maritime law, but also to ensure the Russian control over lines of transport on the world’s oceans and unimpeded access to oceanic resources (biological, energy, etc). Russia sees military force as the main instrument of maritime policy implementation.

Tactically, Russian maritime policy is implemented in several ways:

- Legally (e.g expansion of the RF continental shelf through the UN Commission decision)

- Militarily (e.g. aggression against Ukraine)

- Mixed – Through the use of economic, legal, and military levers of influence (including the latest technical inventions).

Russian maritime policy, like all of its foreign policies, can be characterized by flexibility in choosing the means of influence. A constant characteristic can be considered only the ultimate goal – to control or domination of the RF over certain areas of the oceans and to provide parity of maritime influence with the United States.

As a weaker state, RF can compete or confront other global actors only in asymmetric ways, resorting to local actions in the vacuum of the security environment. Accordingly, both for Russian foreign policy and maritime policy, Russia’s most favorable environment is instability and conflict. Therefore, tactically, Moscow tries to destabilize the situation in the area of its interest (Baltic Sea), or save the conflict potential for the future with the possibility of intervention (Caspian Sea). The tactical feature of RF’s maritime policy is its focus on customary law, which allows us to count on the actual changes in the political situation in the historical perspective. For more thorough coverage of the features of Russian maritime policy, it is advisable to apply a regional approach.

The Russian Federation’s Maritime Policy in the Arctic

The principles of the RF’s Arctic policy determine that the Arctic is a strategic resource base, a strategically important territory for Russian foreign and security policy, and assumes that all activities in the Arctic are of maximum importance to the state’s interests in security and defense. The RF’s Arctic policy is determined by a large number of official documents, as listed above, and the following:

- Foundations Of The Russian Federation’s State Policy In The Arctic (2001)

- Foundations of the Russian Federation’s State Policy In The Arctic Until 2020 And Beyond (2008)

- The Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and National Security up to 2020 (2013)

Russia’s maritime policy in the Arctic implements two priority goals: to consolidate Russian sovereignty over the North Sea Route (NSR) and to expand the area of sovereignty of the Russian Federation over the Arctic shelf. Today, Moscow has unilaterally established a legal regime of inland waters over the NSR. RF’s claims for exclusive rights to use the sea shelf are currently under scrutiny at the UN.

The North Sea Route

The Russian approach (Federal Law №155, Article 14, 1998) to the substantiation of the policy on the NSR and maritime policy generally relies on: 1) Russia’s claims of historic rights in a particular region; 2) The norms of international law, including UNCLOS (1982). In justifying its sovereignty over the NSR, Russia relies on two UNCLOS articles — 234 and 236 (Mikhina, 2015).

The Russian legal regime of the NSR established the status of inland waters for the entire North Sea Route (see Annex 1). In 2012, the federal law of RF cancelled the notion of “Route of NSR” and introduced the concept “Sea Area of the NSR” (The Federal Law №132-FZ, Article 5.1., 2012) and in 2013 the ministry of the RF ordered (Rules of navigation in the water area of the Northern Sea Route, 2013) that the waters of the NSR are to be considered the national line of transportation for the RF.

The legal regime, which Moscow introduced for the waters of the NSR among other things, suggests that the shipowner, or the captain of the vessel, intending to transit the NSR must apply for transit from the administration of NSR for temporary permission at least 15 days in advance. In addition, all vessels approaching the borders of NSR must notify the administration of the NSR 72 hours in advance and provide a daily report on the movement and status of the vessel.

Among the legal bases of the special legal status for NSR, Russian lawyers define the following:

- Article 234 UNCLOS, which gives Arctic states the right to adopt laws and regulations in the ice areas of the 200 mile EEZ to protect the marine environment;

- The status quo of the Arctic region, which provides for an indisputable legal priority of the Arctic States and is enshrined not only by the normative legal acts of the Arctic States, but also by clearly pronounced or silent international recognition;

- There also exist “similar” practices in the maritime politics of other countries. Notably, it concerns the legal regime of inland waters. For example, Canada made claims to the Northwest Passage in 1986 (NWP). It stated that the transit of all foreign ships is allowed but subject to Canada’s legislation on regulation of the pollution of seas from ships. Foreign warships could enter Canadian inland waters and ports in accordance with the permit, which they should submit for to the Foreign Ministry of Canada at least 45 days in advance. Another example is the delimitation of the Norwegian fisheries zone and territorial waters by the Norwegian Government Decree (1935) and the positive conclusion of International Court of Justice concerning the Norwegian claims (1951).

An important precedent in Russia’s non-recognition of the international legal regime of the NSR’s inland waters is the “Arctic Sunrise” case. The icebreaker of the international non-governmental organization Greenpeace was detained along with its crew by Russian border guards in August of 2013. Of significance was that the vessel “Arctic Sunrise” was in accordance with Russia’s rules for the water area of the NSR (three authorization requests were made and denied before the crew decided to continue its transit) (Berseneva, 2013). However, in the judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (Press Release. The Arctic Sunrise”Case, 2013), the actions of the crew were considered legal and within the realm of UNCLOS. In May 2017, the Netherlands and Russia released a joint statement announcing the final resolution of the dispute regarding the detention of “Arctic Sunrise” on the International Tribunal’s judgment.

The Arctic Continental Shelf

In defending its positions and interests in the Arctic in general and on the shelf in particular, the RF utilizes symbolic, legal, and military means. One of the brightest symbolic gestures was Russia’s placement of its flag on a titanium plate on the submarine ridge of Lomonosov in the North Pole in 2007.

In the legal sphere, the RF is trying to assert its rights to the Arctic continental shelf through a mechanism of approval and the respective application of the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). In 2016, Moscow submitted an updated and supplemented application for expansion of the border of the Arctic continental shelf by 1.2 million sq. km. (See Annex 2)

For reference: Russia’s opponents to this application are other Arctic states; Denmark, Norway, Canada and the United States. Denmark also claims to expand its own territory of the Arctic shelf by 900 thousand sq. km. Norway filed a request in 2006 and was the first to receive a positive decision by the Commission. Denmark submitted its application for consideration to the Commission in December 2014, and Canada in May 2019. The claims of Russia, Denmark, and Canada all partly intersect.

The issue of establishing national claims or sovereignty over the territory of the Arctic continental shelf is based on economic interests. Present in the disputed territories is approximately 13% of world oil reserves, 30% of gas reserves, and significant deposits of other useful minerals to include rare earth materials. Any solution to be found will be based not only on scientific evidence, but also on a political basis.

Experts predict various scenarios in the event that Russia’s application will be rejected by the Commission (Moe, 2011; Zagorskiy, 2013; Konyshev & Sergunin, 2014). The least probable scenario is the RF’s exit from UNCLOS and a unilateral declaration of Russian sovereignty on the expanded territory of the Arctic continental shelf. In this case, Russia will be in the U.S. position, outside of UNCLOS, and will rely on customary law and military force to substantiate its claims. It is believed that this is an extreme and unlikely step, since the positions of Moscow in this case would be weaker than the Commission’s decision. The second scenario involves reviewing their position and submitting a revamped, less ambitious, claim. This step will demonstrate respect for international law, but can provoke internal discussions within Russia. The third and most likely scenario, in the case of a negative decision, is to abandon the issue for a more favorable political circumstance and instead ensure Russia’s actual dominance over the region via military presence.

The important thing for Russia’s Arctic policy is that it is implemented by the RF as the sole presence in the region. Although other states declare their interest in the Arctic and protest against the spread of Russian sovereignty beyond the bounds of maritime law, there is no real competition for Russia’s presence there in the near term, although the first steps in this direction have been made by China. Therefore, the Arctic projects of the Russian Federation (NSR and continental shelf expansion) are a convenient opportunity for Moscow:

- To consolidate and secure the actual state of affairs until they become part of the legal order (customary law, tacit recognition).

- To strengthen the legal validity of the category of “historicity,” which is widely used by the Russian Federation to legitimize its interests and actions at sea and in other regions.

Both of these Russian policies are relevant to the Ukrainian-Russian confrontation. On one hand, Russia justifies its aggression and the illegal annexation of Crimea to the “historical affiliation” of these territories to Russia and lays the principle of “historical inland waters” for the Azov Sea in the legal field of Ukrainian-Russian relations. On the other hand, it tries to consolidate the Crimean situation in the international political field as the situation has developed.

Part of the Arctic policy of Russia is its relations with Norway in the Barents Sea and with the U.S. in the Bering Sea and Strait. Both directions of Russia’s relations have some incompleteness and conflict potential, and therefore the difference between these Russia’s approaches is worth exploring:

Russia – The USA, Bering Sea, and Bering Strait

The Bering Strait is the only access point for all the states of the Asia-Pacific region to the Arctic Ocean. Due to the fact that the width of the strait is less than 24 miles, its entire water area is covered by inland seawater and the territorial seas of the Russian Federation and the United States. At the same time, both States recognize the status of a transboundary used for international navigation and covered by the transit passage law (UNCLOS, Article 38). The Bering and Chukchi Seas are important for the fishery industries of both countries.

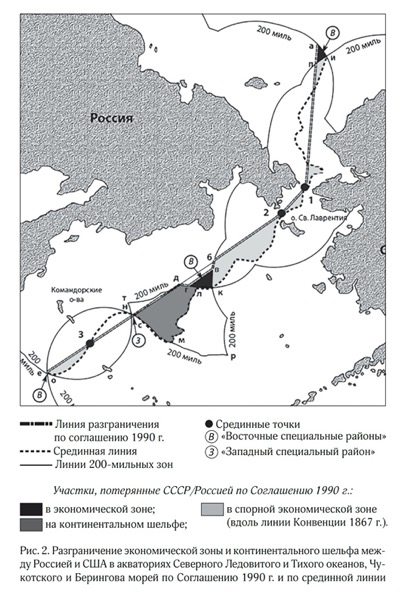

The maritime boundary in the Bering Strait and in the Bering and Chukchi Seas between the Russian Federation and the United States (also known as the Baker-Shevardnadze Line) was established by the agreement on the maritime border between the United States and the USSR of June 1, 1990. The agreement is ratified by the United States and not ratified by Russia. The agreement has been criticized by Russian officials and lawyers as having led to territorial and economic losses in the Russian Federation, in particular, with regard to the development of shelf and seabed resources (see Annex 3) (Tkachenko, 2017).

Despite the Russian Federation not ratifying the treaty, the parties adhere to the regime of maximum silence and the avoidance of provocations at the border. While the rhetoric of the United States and Russia is acute in relation to Ukraine, Syria, and Russia’s provocations in the Baltic region, in the Bering Strait during the past 10 years, the level of tension has remained steadily low; Russian military aircrafts and vessels are strictly adhering to territorial boundaries (Hawksley, 2015).

The United States relies on the principle of long-term common practice as evidence of the current international legal status of the border and the effectiveness of the treaty. This principle is part of international customary law and can legitimize a treaty whose entry into force has not been completed (Konyshev & Sergunin, 2014). For its part, Moscow uses the 1990 agreement to substantiate its claim to expand the Russian territory into the Arctic shelf. This conundrum makes it impossible for Russia to renounce this agreement even if the Duma refuses to ratify it further (Laruelle, P.104., 2014,). Today, discussions and dialogue between Russia and the United States on Bering Strait issues are being conducted regularly, only not for territorial issues, but for fisheries.

For Reference: Russian claims to sovereignty over the areas from the Arctic sea to the North Pole were fixed in the Resolution of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of 1926 “On the declaration of the territory of the Union of SSR lands and islands located in the Arctic Ocean.” This document defined the western boundary of the Russian Arctic possessions by a median of 168° 49 ’30” west longitude from Greenwich – just in the middle between the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait, which was then confirmed by the US-Russia Convention. At that time, territorial waters were restricted only 3 miles of sea from the shoreline (cannon shot), and so the Convention on the Purchase-Sale of Alaska did not define a boundary in the Bering Strait and Sea.

Russia-Norway: The Barents Sea, Svalbard/Svalbard

In 2010, after 40 years of negotiations, Russia and Norway settled a bilateral dispute over the maritime boundary and signed an agreement on the so-called “Grey zone” (175,000 sq. km.) on the shelf of the Barents Sea.

For Reference: The factors that have resulted in a compromise between Russia and Norway (Konyshev & Sergunin, 2014):

- Both countries have signed and ratified UNCLOS, which unified the national rules of delimitation of the continental shelf and EEZ (as the Convention provides identical rules based on the median principle, rather than the sectoral principle of demarcation of Sea territories);[1]

- Both countries took into account the decisions (a few in the 90 ‘s and 00 ‘s) of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the principle of resolving sea disputes. The court determined that disputes should be resolved according to the principle of objective geographical factors, where there can be significant differences in the length of the coastline;

- Favorable political circumstances have emerged for Norway. This dispute was the last in the settlement of relations with Arctic neighbors, and in 2009 Oslo received a CLCS decision on the boundaries of its continental shelf and EEZ in the Arctic. It was important for Moscow to demonstrate goodwill and contractual capacity for a diplomatic fight with Denmark and Canada over the Arctic shelf;

- Both countries were interested in exploring the Barents Sea’s hydrocarbon resources

However, the signing of this agreement did not solve other problematic issues of bilateral Russian-Norwegian relations such as those regarding fisheries, energy production, and Russia’s desire to strengthen its presence in Svalbard/Spitsbergen.

Svalbard’s problem

Background: Svalbard’s status is governed by the Treaty of Paris on the Svalbard Archipelago of 9 February 1920, which recognizes Norway’s sovereignty over the archipelago and obliges it to secure certain rights of other signatories to the treaty. The USSR formally recognized the sovereignty of Norway over the archipelago in 1924 through the exchange of notes. The USSR became a party to the Treaty of Paris in 1935. Today, about 40 countries have joined the Treaty.

The conflicts between Russia and Norway in the context of the legal regulation of activities in and around Svalbard have an economic and security dimension. In the economic sphere, Russia is questioning (Portsel, 2011; Oreshenkov, 2010):

- There exists a 78% income tax rate that the archipelago’s offshore energy companies have to pay to Norway. Russian companies believe that they enjoy the opportunities provided for by the 1920 Paris Treaty, namely the right to pay taxes less than 1% of the value of the product extracted.

- Oslo decided in 1977 to establish a 200-mile fishing protection zone around the archipelago. Russia has not recognized Norway’s decision and considers these territories to be open to international economic activity, including fishing. Therefore, incidents have occurred between Russia and Norway, during which Russian fishermen have been arrested by Norwegian coast guards. In 2004, the Russian Northern Fleet began patrolling around Svalbard to protect Russian fishermen. Norway declared the practice unlawful and that it was a manifestation of Russia’s imperial ambitions and Moscow’s unwillingness to cooperate to resolve the issues at hand.

A problematic issue for Norway in the field of security is Russia’s desire to expand its presence and operations in Svalbard. Oslo sees this as a threat due to its historical experience with the USSR’s Svalbard policy (Portsel, 2011) and generally with Russia’s current aggressive policies. In respose, Norway has intensified restrictive measures: blocking plans for the construction of facilities (such as fish processing plants), extending conservation areas within which Russian scientists and tourists are restricted, establishing rules for the registration of all scientific projects in a special database, etc. The Russian side, in response, restricted the access of Norwegian researchers to the Barents Sea’s bioresources within its EEZ. These issues are the subject of ongoing Russian-Norwegian negotiations.

For Ukraine, examples of Russia’s maritime policy in the Barents Sea, Svalbard, in the Bering Sea, and the Strait once again confirm that the most powerful argument for Russia to refrain from provocations and conflicts in bilateral relations at sea is the power of its adversaries. Both waters contain enough contentious issues to intensify the confrontation. If Moscow refrains from even hints of provocation in the Bering Sea and the Straits, then it will also have no intention of expanding its boundaries or influence in the Barents Sea and at Svalbard.

The Baltic Sea

Like the Barents Sea, the Baltic Sea is a place of intense interstate relations with the participation of the Russian Federation and NATO nations. RF has no unresolved territorial issues in the Baltic Sea. Maritime borders with other countries are fixed and enshrined in interstate treaties. A factor that adds to the uncertainty of the overall situation is that Moscow has not yet ratified the Treaty between the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Estonian-Russian border and the Treaty between the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Delimitation of the Maritime Zones in the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Narva. The Russian Foreign Ministry argues that ratification is delayed because it is possible only in the absence of confrontation in relations between the two states (Lavrov, press-conferece, 2017).

The Baltic Sea Region is the least conducive to establishing Russian maritime domination. There is no conflict potential in this geographical area that Russia could use to enhance its political weight and increase its military presence beyond Russian territory. At the same time, the high level of Russian military presence in the Baltic Sea area and the policy of systematic provocations by Moscow fulfill the following functions:

- Demonstrates the continued presence of the Russian Federation in the Baltic Sea and its importance as a Baltic state;

- Provides ongoing intelligence to identify potential military threats to Russian infrastructure and military installations in the region;

- Provokes the North Atlantic Alliance to respond to the threat posed by Russia in this region, resulting in their underestimating of the level of threat in other areas.

Russian maritime policy in the Baltic Sea closely integrates the economic and military components. According to an analysis by the Center for Global Studies “Strategy XXI”, the infrastructure of the Russian Nord Stream pipeline (1 and 2) can be used to gather intelligence and military information on NATO’s activities in the Baltic Sea (Honchar & Hayduk & Burhomistrenko & Lakiychuk, 2018).

The Russian instrument of influence and destabilization in the sea waters is also the artificial disorientation (jamming and spoofing) of the GPS/GNSS satellite navigation systems. According to a study by the American non-governmental organization C4ADS (March, 2019), since February 2016, there have been approximately 10,000 cases of Russian interference with the satellite navigation systems. Among the latest known cases of this kind are the Russian interference with GPS navigation during the NATO-led Trident Juncture exercise in October 2018, as officially announced by the governments of Norway, Finland and NATO officials (O’Dwyer, 2018), and failures in the GPS navigation system in the Sea of Azov at the same time as the Russian GLONASS system worked without fail (Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, 7 March 2019).

Caspian Sea

Since the Caspian Sea has no natural access to other seas, for a long time there has been controversy over the legal regulation of its waters, specifically around the legal approach to the nature of this body of water – “sea or lake.” The status of the Caspian Sea was undefined and first relied on agreements between the two countries, Iran and the USSR. After the collapse of the latter, the status relied upon bilateral and multilateral agreements of coastal countries that required codification up to the signing of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in 2018. The legal regime in the Caspian Sea is not governed by UNCLOS or other offshore instruments.

Russia’s interest was, and remains, in maintaining its maximum impact in the Caspian Sea. For this, the sea must be “closed” to external states and free for the use of resources and the movement of military vessels. The main tool for securing Russian interests in the Caspian Sea is the naval forces of the RF. Russia’s military superiority over other Caspian states, combined with political influence, make it possible for Russia to prevent the implementation of economic projects that are disadvantageous to its interests, for example, the construction of the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline. The RF has gained additional leverage thanks to the conclusion of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea (2018), which on one hand provides the conditions for the completion of the delimitation process of the maritime borders of the Caspian states, and on the other hand creates such a legal regime of this water area, which completely satisfies Russia, namely:

- Provides for the right of free movement of the Caspian Navy outside the 25-mile zone to which coastal country sovereignty extends (territorial waters + fishing zone) and blocks non-Caspian military presence in the Caspian Sea;

- Leaves the delineation of the sea floor uncertain. Such demarcation is envisaged to be in accordance with the agreements of the neighboring countries (Article 8). This approach was used in 1998-2003 to delimit the Caspian Sea between Russia, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan (Bratchikov, 2018). Thus, the potentially conflicting issue of the allocation of Caspian energy production rights between Iran, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan remains a favorable environment for the implementation of Russian policy;

- Contains a mechanism for blocking the construction of pipelines along the bottom of the Caspian Sea (Ibid). The text of the Convention does not require the consent of all coastal States to lay pipelines and requires the agreement of only the countries in whose sectors the pipe should pass. However, the possibility of blocking such projects is envisaged by the binding Convention (paragraph 14, Article 14) to the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea and its Protocols, in particular the Protocol on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context, according to which each country in the Caspian Sea may express its disagreement about conducting activities in the Caspian Sea.

Examples of Russian maritime policy in the Baltic and Caspian Seas for Ukraine can be seen in terms of the implementation of RF’s goals in these two completely different environments. In both waters, the main tool for the strengthening of Russian political influence and presence is military force. In the stable Baltic Sea, with its low level of conflict, the Russian Navy has resorted to provocations and demonstrates its presence to create a conflict, while in the Caspian Sea with its number of uncoordinated issues between the littoral States, information about the provocative behaviour of the Russian Navy is not received, because such conflict can be quickly created there by the RF if necessary. This confirms the thesis that conflicting and unstable environments are the most favourable for the implementation of Russian policy. Respectively, the actions of the RF will always be directed either to constrain and conserve conflict potential in a certain region, or to destabilize the regional environment.

Maritime policy of Russia in the Far East and territorial dispute between Russia and Japan

In the Far East, the most problematic maritime issues for the Russian Federation are with Japan. The two States have a long history of maritime relations, the core problem of which was and remains the territorial identity of the islands of the Kuril Archipelago. In addition to this matter, other interesting examples of Russian maritime policy that can be seen in the Japanese and Okhotsk Seas are the issues of shelf and legal regimes; the use of water resources of the Okhotsk Sea and the desire of Russia to declare the Gulf of Peter the Great a territorial sea.

Russia claims to the waters of the Gulf of Peter the Great in the Sea of Japan as a proper territorial sea, the boundaries of which are defined by direct rising lines from the extreme points of the bay. Japan, France, UK, and the USA do not agree with this position. Moscow’s reasoning is built mainly on the fact that this bay is the “historical gulf” of the Russian Federation, respectively, its status is regulated by the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, and the boundaries of Russian sovereignty are determined by UNCLOS article 7 and article 10 paragraph 6.

For Reference: In 1957, the USSR announced the Gulf of Peter Great as its inland waters. U.S., Japan, France, and Britain refused to acknowledge this decision on the grounds that the width of the entrance to the Bay of 102 miles, which considerably exceeds the limit of 24 miles set by UNCLOS. Moscow, in response, stated that the Gulf of Peter the Great belongs to the category of “historical bays,” which was defined by Russia in 1901 in the rules of maritime fisheries in the territorial waters of the Amur Governor-General, as well as in the contracts with Japan on Fisheries 1907, 1928 and 1944 (Rezchikov & Trubina, 2018).

Sea of Okhotsk

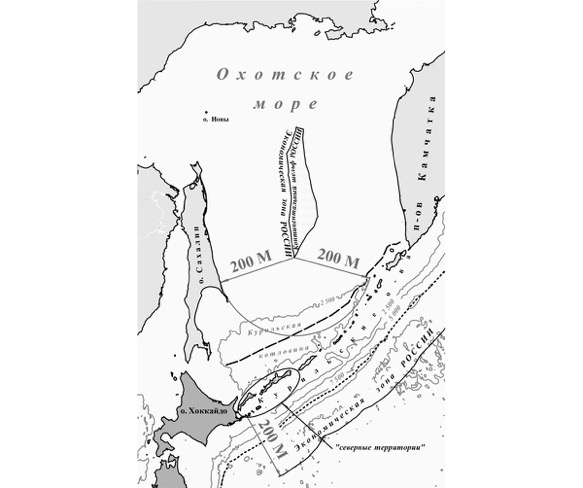

In 2014, the UN Commission on the borders of the Continental Shelf adopted a positive decision on the Russian application for expansion of the borders of Russia’s continental shelf in the Okhotsk Sea. As a result of this decision, the central part of the Okhotsk Sea (52,000 sq. km.) was included in the RF Continental shelf (Reccomendations of the CLCS, 2014).

Comments from the Russian side, including from Russian officials, contain the statement that since the approval of the Russian application by the Commission, the Sea of Okhotsk has become a Russian Inland Sea (Zykova, 2014).

Such statements, however, are untrue because of Russia’s existing limit of a 200-mile EEZ in the Okhotsk Sea. Russian sovereignty over the central part of the Okhotsk Sea shelf does not apply, to include the water and bioresources that are contained in therein (shrimp, shellfish, crabs, etc.) (Art. 78, UNCLOS). The legal regime of fisheries for both Russian vessels and those of other nations in the central zone is not altered by a decision of the Commission, but the aspects of cooperation between offshore energy and fishing companies that have economic interests in this part of the sea are subject to clarification (Kurmazov, 2015).

The coastal country of the Sea of Okhotsk is also Japan, and the experience of Russian-Japanese relations in the maritime sphere is especially important for Ukraine.

The Kuril Islands

Officially, Tokyo has a rather rigid position, requiring Russia to transfer to Japan part of the southern Kuril Islands; Iturup Island, Kunashir Island, Shikotan Island, and Habomai Island. (see Annex 4)

Arguments of the parties (Masiuk, 2015)

| Japan | Russia |

| The islands were occupied by the USSR between August 14, 1945, when the Japanese emperor announced the surrender of Japan, and September 2, 1945, when the Unconditional Capitulation Act was signed. During this time, Soviet troops continued the fighting and captured the islands. | The fighting ceased after the official surrender, which was recorded on September 2, 1945. Before this time, however, Japanese forces had stopped resisting. |

| The affiliation of the islands of Japan is fixed by the treaties: the Shimodo Trade Treaty of 1855 (the border was drawn between the islands of Urup and Iturup and Sakhalin was unbounded) and the St. Petersburg Treaty of 1875 (Japan recognized Sakhalin as Russian in exchange for transferring all the Kuril Islands ). As a result of the defeat of Russia in the war with Japan in 1904-1905, according to the Portsmouth Peace, Russia ceded Japan to all the Kurils and Southern Sakhalin. | The complete and unconditional surrender “nullified” the subjectivity of the state; accordingly, Japan cannot rely on international treaties that existed until 1945. |

| Soviet-Japanese Declaration of October 19, 1956 states the end of the war and the readiness of the USSR to hand over to the islands of Habomai and Shikotan after the conclusion of the peace treaty.[2] | The declaration is not a contract but a protocol of intent. |

| Japan’s actual recognition of the Soviet border in the Kuril Islands is a fishery agreement signed by the USSR. In particular, the 1963 and 1981 agreements. “Japanese fishermen … must abide by the laws, regulations and rules of the USSR in force in the area” (Soviet-Japanese Seaweed Agreement, 1981). |

The unsettled territorial issues between Russia and Japan are an obstacle to the signing peace treaties between the two countries, but this situation does not prevent Japan and Russia from developing broad bilateral cooperation. In doing so, Russia has successfully used Tokyo’s territorial aspirations as a factor in influencing Japan’s position on various issues. Indeed, it is safe to assume that Tokyo’s hopes for more productive island-negotiations influenced Japan’s decision to refrain from protesting Russia’s claims to expand the continental shelf in the Okhotsk Sea in 2013, as opposed to protesting Russia’s bid in 2001 (Kislovskiy, 2016).

The main peculiarity of Japan and Russia’s bilateral relations in terms of maritime policy in the area of the disputed islands is Japan’s actual compliance with the rules and regulations established under Russian sovereignty over the islands and the maritime space around them. In this area of the sea formed a special type of economic relations between the two countries, due to the acute dependence of the population of islands on both sides of the marine fisheries.

For Reference (Kurmazov, 2006): After WWII, Japanese fishermen who continued to fish near the USSR-controlled islands were often delayed by Soviet border guards (1534 Japanese fishing vessels were detained in 30 years, from 1945 to 1976, and only 939 returned). The magnitude of the problem for the Japanese population can be seen from the fact that in 1962, the Government of Japan established a fund to assist the fishermen’s families who were detained by Soviet border guards. The All-Japan Fishermen’s Association officially raised the issue of offshore fisheries in Tokyo by negotiating with Moscow in the early 1960s. The result was a 1963 agreement between the State Committee for Fisheries of the USSR Council of National Economy and the All-Japan Association of Fishery Producers for fishing for sea cabbage by Japanese fishermen in the area of Fr. Signal (Kaigar).

Fishing for Japanese sailors in the waters controlled by the USSR was governed by interagency agreements. Noteworthy is the agreement signed in 1981 after being proposed by the USSR in 1977 regarding Japan’s 200-mile EEZ. The features of this agreement are (Kurmazov, 2006. pp. 349-350):

- the obligation of the Japanese side enshrined in Article 5 to comply with the laws and regulations of the USSR, as well as to pay for fishing rights;

- Asymmetric characteristics (from the Soviet side – the state department, from the Japanese – a public organization);

- Not ratified by the parliaments of the countries;

- Has the status of an international agreement through the exchange of notes of the Foreign Ministry of the USSR and Japan.

In 1998, another agreement was concluded between Russia and Japan, which this time was intergovernmental. It does not have an article similar to Article 5 of the 1983 Agreement, but there is an Article 3, part of which reads “The Parties, where appropriate, shall encourage the development of mutual cooperation between organizations and corporations of both countries in the field of fisheries within the scope of their respective relevant laws and regulations of the respective countries.”

Today, the Russian side adds to the list of arguments regarding Russian affiliation with the Southern Kuril Islands, the existence of two treaties – from 1983 and 1998 and the fact that Japan’s fisheries operate in the respective sea areas under Russian laws and international treaties with the Russian Federation (Kurmazov, 2006. P.354).

For Ukraine, the historical experience behind Russia’s maritime policy in its relations with Japan is valuable because of the parallels of the forced coordination of economic activity in the conflicted maritime area. Despite the different nature of the territorial conflict with the RF in Japan and Ukraine, the means and instruments of Russian maritime policy are similar in both cases and can be taken into account by Kyiv to secure its position in the future.

The Azov and Black Seas

The maritime areas of the Azov and Black seas do not differ in the severity of relations from the rest of the maritime areas where the RF is present. Cases of persecution and the detention of fishing vessels took place between the USSR and Turkey. After 1991, they continued between Ukraine and Turkey, Ukraine and the Russian Federation, Ukraine and Romania, etc. These incidents were resolved through the application of administrative measures; fines, etc., and counter-claims through legal, political, and diplomatic mechanisms. With the onset of Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2014, the situation has changed dramatically as Russia, in the Black and Azov Seas, has begun to militarily reinforce the region with all of its experience in asserting dominance over other marine areas.

Today, in the Azov and Black Seas, the Russian Federation achieves its goals through a combination of military and economic means of influence. All coastal states are the object of Russian policy in the Azov-Black Sea area, but Moscow’s focus is currently on Ukraine and Turkey. The purpose of the maritime policy of the RF in this maritime space is to completely absorb it into the sphere of Russian domination both economically and militarily.

The Sea of Azov

The actual control over the Sea of Azov, which Russia acquired as a result of the occupation of the Crimean peninsula, the construction of the Kerch Bridge, and the preserved contractual regime with Ukraine, provides for it virtually unlimited possibilities of presence in the Azov maritime area and the use of its biological resources. Today, Ukraine is limited in its ability to impede Russia’s actions in the Azov Sea. Using its military advantage and effective control of the Kerch Strait, Russia has blocked the Azov Sea for Ukrainian warships and is restricting merchant shipping to the ports of Berdyansk and Mariupol. Russia’s actions in the Sea of Azov indicate that Moscow is implementing a strategy of the gradual maritime economic isolation of Ukraine in the Azov-Black Sea basin.

In the conditions of restricting third-party countries’ access to the Sea of Azov under the Agreement between Ukraine and the RF on cooperation in the use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait of December 24, 2003, and the military advantage on the part of Russia, the threats of isolation of the Azov coast of Ukraine increase significantly. To achieve the goal of isolating Ukraine’s Azov coast, the RF applies both administrative and procedural methods such as controls, inspections, the creation of artificial pretexts for long delays of ships. It also asserts military methods such as the closure of certain sections of the Azov Sea under the pretext of naval exercises.

The Azov waters actually became the area of collision between the Russian Security Forces (FSB) and Ukrainian Naval Forces. The obstacles that Russia implements to subvert Ukrainian economic activity in the sea, namely fishing and commercial ports, aims to destroy the region’s economy and cause further political destabilization.

It is not necessary to exclude the probability of Russia’s manipulation of the existing agreements with Ukraine, both the agreement dated 2003 and annual protocols on fisheries in the Sea of Azov, to strengthen the Russian political position in its confrontation with Ukraine.

Today, Ukraine does not rely upon Russia’s compliance with its agreements within the current legal framework and Ukraine is limited in its options to protect its interests and defend its rights in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait.

Ensuring the rights of merchant vessels to a smooth passage of the Sea of Azov to ports in Berdyansk and Mariupol is effectively achieved only by using military means. The obstruction of Ukrainian Navy ships is attempted by the RF’s FSB to commit illegal inspection stops.

The Black Sea

Russia views the Black Sea and the Black Sea region not only as a zone of influence, but as a necessary foothold for its presence in the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, North Africa, and also to strengthen its position there. Accordingly, Russia’s Black Sea strategy combines two goals:

- To block Ukraine from the sea as part of a strategy to restore control of Ukraine,

- To acquire undisputed dominance in the Black Sea by limiting NATO countries’ activity in the area and the unimpeded use of the Turkish straits.

Russian Black Sea domination, which also includes Russia’s role in frozen conflicts in the region, will allow Moscow to: 1) influence the economic and political activities of the Black Sea states, 2) to control the trade and energy routes of the Black Sea from Europe to Asia. In this case, Russia will be able to maintain its monopolistic position of energy supplier to EU countries and may strengthen its political influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

Russia’s only competitor for influence in the Black Sea and the South Caucasus may be Turkey, whose naval power still prevails over Russia (Wezeman & Kuimova, 2018). Turkey also controls the passage through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

At the same time, Turkey is vulnerable to Russian influence. Its strategic transport and energy transit projects depend upon maintaining stability in the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea, where Russia’s military and political presence is significant. Joint Russian-Turkish energy projects (Turk-Stream 1 and 2) may in the future become an instrument of Moscow’s influence over Ankara.

Particular attention is paid to Ankara’s concession to Russia in interpreting the provisions of the Montreux Convention, taking into account reports of passage of the Russian submarines “Veliky Novgorod”, “Kolpino”, “Krasnodar,” and “Stary Oskol”, which could be considered violations of Article 12 of the Montreux Convention (Zender, 2019).

Turkey today complies with the rules of the Montreux Convention and is interested in doing so in the future to preserve the convention and to protect the Turkish interests in the Black Sea. At the same time, Ankara’s plans to build an alternative (parallel) Bosphorus-Istanbul Canal deserve special attention and study. It is not inconceivable that the existence of this channel may provoke discussions on the extension of the rules of the Montreux Convention to it, as a whole and its separate provisions. It is not excluded that in the future, Ankara may decide to build an additional canal parallel to Dardanelles, which will create a fundamentally new geopolitical reality in the Black Sea region and put on the agenda the need to review the legal use of straits.

We can assume that Russia considers the prospect of building alternative connecting channels between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea as an opportunity to create a new legal regime for the passage of vessels in and out of the Black Sea. This could also be used to limit the possibility of warships from non-Black Sea states from entering the sea. Additional grounds for the Russian military presence in the area of the Black Sea Straits and their control may appear after the completion of the Turkish Stream, as Moscow traditionally uses such infrastructure as a pretext for military or intelligence activities (Burhomistrenko & Haiduk & Honchar & Lakiychuk, 2018).

The Black Sea region has today become an area of power dominance. In the secondary role of international law, only high-security states (military power, security alliances) are able to protect their own interests as a guarantee of security. This state of affairs is entirely in the interests of Russia. And since Moscow in this case is a provocator of chaos in the region, the situation and the return to a relationship based on international law should not be expected in the near to medium term. To change the political situation, any general regional formats of cooperation in the economic, humanitarian, or environmental protection arenas have no future because they will not be based on common interests.

Today, the main threat to Ukraine in the Black Sea is Russia’s aggressive intentions and behavior through the further destabilization of the southern regions of Ukraine. The initial stages of this can be the establishment of Russian control over shipping to the Black Sea ports of Ukraine: Odessa, Nikolaev, Kherson and the mouth of the Danube.

Control over the Crimea and the installation of intelligence equipment on the drilling and extraction platforms of the Ukrainian state company “Chornomornaftogaz” give the RF Black Sea Fleet the possibility of conducting radio and electronic intelligence operations (Ibid.). The constant military presense of Russian warships near these facilities is a demonstration of the RF’s claims to “rights” in this part of the Black Sea waters.

Conclusions

- The modern maritime policy of the RF is strategically focused not only on the protection of sovereign rights of the RF in the waters belonging to it according to maritime law, but also on ensuring Russian control over transportation lanes in the world’s oceans. Furthermore, RF seeks unhindered access to the resources of these global commons (biological, energy, etc.). The ultimate objective of RF’s maritime policy is to provide parity of maritime influence with the USA.

- Russia’s maritime policy is implemented through a combination of military force, political and legal instruments, economic impact, and new means of technical influence. With the beginning of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the value of military force for the RF as a tool for achieving maritime policy objectives has prevailed over other means.

- Security, instability, and conflict are the most favourable environments for the implementation of RF’s maritime policy objectives. Therefore, Moscow is tactically trying to destabilize the situation in the areas of its interest (Baltic Sea), or to preserve the conflict potential for the future with the possibility of intervene (Caspian Sea).

- RF’s maritime policy relies on the existing normative foundation of the law of the sea. In those cases when RF cannot reach its desired goals through military means, the RF relies upon the decisions of these competent international bodies. In cases of Russia’s violation of international and maritime law, it captures the status quo by power and counts on the legitimation of its actions in the future through the principles of political expediency, customary law, and “Historicity.”

- Striving for parity with global actors in the maritime sphere, the Russian Federation, as a weaker state, rests on the law of the sea and declares compliance with its norms. At the same time RF prefers the application or demonstration of military force in relations with other countries.

- In the Arctic region, RF prioritizes two goals: to consolidate Russian sovereignty over the North Sea and to expand the area of the sovereignty of RF over the Arctic shelf. The important thing for Russia’s Arctic policy is that it is implemented by the RF as the sole presence in the region. Russia’s accelerated militarization of the Arctic creates convenient conditions for Moscow to:

- To consolidate and secure the actual state of affairs until they become part of the legal order (customary law, tacit recognition).

- To strengthen the legal validity of the category of “historicity,” which is widely used by the Russian Federation to legitimize its interests and actions at sea.

- In the Bering Strait and Bering Sea, despite the lack of ratification of the treaty that delimits it, Russia observes a policy of silence and the avoidance of provocations on the border with the USA.

- In its relations with Norway in the Barents Sea, despite the resolution of maritime border issues and the disputed “grey zone,” the RF continues to not recognize the Norwegian legal status of sea areas around Svalbard with respect to fisheries regulation and energy production. For Norway, the primary issue is Russia’s desire to strengthen its own presence near Svalbard/Spitsbergen.

- While the region of the Baltic Sea is the least favorable for the establishment of Russian maritime domination, the high level of Russian military presence in the Baltic Sea and the policy of systematic provocations by Moscow serve the following purposes:

- Demonstrates the continued presence of the Russian Federation in the Baltic Sea and its importance as a Baltic state;

- Provides ongoing intelligence to identify potential military threats to Russian infrastructure and military installations in the region. It also serves to identify “weak areas” in Baltic states;

- Provokes the North Atlantic Alliance to respond to the threat posed by Russia in this region, resulting in their underestimating of the level of threat in other areas.

- The main tool used by Russia to pursue its interests in the Caspian Sea is naval power. Additional influence, however, is leveraged by the RF through the convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea. On one hand, it provides the conditions for the completion of the delimitation of the maritime boundary of Caspian states. On the other hand, the creation of such a legal maritime regime is quite satisfying to Russia because it does not limit its military presence and provides an opportunity to hinder the implementation of economic projects that it deems disadvantageous.

- In its relations with Japan, the RF now adds to the list of arguments regarding Russian affiliation with the Southern Kuril Islands that Japan’s fisheries in these waters fall under Russian laws and international treaties with the Russian Federation. For Ukraine, the historical experience of Russia’s maritime policy in its relations with Japan is valuable because of the parallels of forced coordination of economic activity in the conflicted maritime area. Despite the different nature of the territorial conflict with the RF in Japan and Ukraine, the means and instruments of Russian maritime policy are similar in both cases and may be taken into account by Kyiv to secure its position in the future.

- Today, in the Azov and Black Seas, the RF achieves its goals through a combination of military and economic means of influence. The subjects of Russian policy in the Azov and Black Seas are all coastal states. The purpose of the maritime policy of the Russian Federation in this maritime space is to completely absorb it into the sphere of Russian domination both economically and militarily.

- Having made a decision on the violation of the norms of international and maritime law in the Azov and Black Sea region, the RF remains within the legal framework where it does not contradict its goals and can help to consolidate the “actual state of affairs.” The most commonly used legal arguments of the RF’s actions in the Black and Azov Seas are the “historical affiliation” of these territories to Russia and the principle of “historical inland waters” for the Azov Sea in the legal arena of Ukrainian-Russian relations.

Annex 1 (Border of the water area of the Northern Sea Route)

Source: The Northen Sea Route Administration

Annex 2 (External border of the continental shelf of RF in the Arctic Ocean)

Source: Itogi raboty Federalnogo agentstva v 2018 godu I plany na 2019 god (2018). [Results of work during 2018 and plans for 2019]. The Federal Subsoil Resources Management Agency. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of the Russian Federation.

Annex 3

Source: (Tkachenko, 2017)

Annex 4

Source: (Kislovskiy, 2016).

* Non-resident Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Bibliography

- Above Us Only Stars. Exposing GPS Spoofing In Russia And Syria. (2019).

- Agreement between the Government of Japan and the Government of the Russian Federation on some matters of cooperation in the field of fishing operations for marine living resources (Provisional Translation) (1998).

- Berseneva, A. (2013). Arktika “zelionykh” ne priyemlet. [The Arctic doesn’t accept “greens”]. ru. 21.08.2013

- Bratchikov, I. (2018). Eto ne rezultat vykruchivania ruk. [It’s not the result of twisted hands]. Kommersant. №167, P. 5.

- Burhomistrenko, A., Haiduk, S., Honchar, M., Lakiychuk, P. (2018). Morska hazova infrastruktura u rosiyskiy protydii NATO na skhidnomu flanzi: potentsial hibrydnoho vykorystannia u Chornomu ta Azovskomu moryakh. [Maritime gas infrastructure in Russian counteraction with NATO on its Eastern flank: potential hybrid usage in the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea]. Chornomorska Bezbeka, 2 (32), 4-22.

- Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea. 12 August 2018.

- Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. April 29, 1958.

- Foundations of the Russian Federation’s State Policy In The Arctic. (2001)

- Foundations of the Russian Federation’s State Policy In The Arctic Until 2020 And Beyond. (2008)

- Fundamentals of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the field of naval operations for the period until 2030. (2017)

- Gezamenlijke Verklaring Van De Russische Federatie En Het Koninkrijk Der Nederlanden Over Wetenschappelijke Samenwerking In Het Russische Arctische Gebied En Het Beslechten Van Een Geschil. Diplomatieke verklaring. 17 May 2019.

- Hawksley, H. (2015). The US and Russia Face to Face as Ice Curtain Melts. YaleGlobal and the MacMillan Center.

- Honchar, Hayduk, Burhomistrenko, Lakiychuk (2018). Hazovi potoky podvijnoho pryznachennia. [Gas pipelines of dual-purpose]. Dzerkalo Tyzhnia. №31.

- Kislovskiy, V. (2016). Napasti anklava Okhotskogo morya. [Adversity of the Okhotsk Sea enclave]. Morskiye vesti Rossii,

- Konyshev, V., Sergunin, A. (2014) Russia’s Policies on the Territorial Disputes in the Arctic. Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy. Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 55-83.

- Kurmazov, A. (2006). Rossiysko-Yaponskoye rybokhoziaystvennoye sotrudnichestvo v rayone Yuzhnykh Kurilskikh ostrovov. [Russian-Japan Fishery cooperation in the South Kuril Islands area]. Izvestiya TINRO, 146, 343-359.

- Kurmazov, A. (2015). Razvitiye pravovogo statusa Okhotskogo moray. [Development of legal statuse of the Sea of Okhotsk]. Tamozhennaya politika Rossii na Dalnem Vostoke. №1(70). 60-67

- Laruelle, M. (2014). Russia’s Arctic strategies and the future of the Far North. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

- Lavrov, S. (2017). Press-conference of the Minister on Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation Sergey Lavrov based on the results of 2017.

- Marine Doctrine of the Russian Federation for the Period Until 2020. (2001)

- Masiuk, Е. (2015). Kurily – “susi” dlia japontsev. [The Kuril Islands – “sushi” for Japanese people]. Novaya Gazeta. № 87

- Mikhina, I. (2015). The UN Convention On The Law Of The Sea and developing the Northern Sea Route opportunities and threats for Russia, RIAC READER. Northern Sea Route.

- Moe, A. (2011). Russia’s Arctic continental shelf claim: A slow burning fuse? In Geopolitical and legal aspects of Canada’s and Europe’s Northern Dimensions, ed. Mark Nuttall and Anita Dey Nuttall. Edmonton: CCI Press. and Zagorskiy, A. (2013). Arkticheskiye ucheniya Severnogo Flota. [Arctic drills of the Northern Fleet]. Aktualnyy kommentariy IMEMO RAN ИМЭМО РАН. in Konyshev, V., Sergunin, A. (2014) Russia’s Policies on the Territorial Disputes in the Arctic. Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy. 2, No. 1, pp. 55-83.

- O’Dwyer, G. (2018). Finland, Norway press Russia on suspected GPS jamming during NATO drill.

- Oreshenkov, A. (2010). Arctic Square of Opportunities. The North Pole and the “Shelf” of Svalbard Cannot Be Norwegian. Russian in Global Affairs. №4.

- Portsel, A. (2011). Spor o Shpitzbergene: tochka ne postavlena. [Spitzbergen dispute: it’s not the end yet]. Arktika i Sever. №3, pp.1-22.

- Postanovlieniye Prezidiuma Tsentralnogo Ispolnitelnogo Komiteta SSSR “Ob ojavlenii territorijej Sojuza SSR zemel i ostrovov, raspolozhennykh v Severnom Ledovitom Okeane, 1926. [The Decree of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR on “The Declaration of lands and islands located in the Arctic Ocean the territory of the USSR”]

- Press Release. The “Arctic Sunrise” Case (Kingdom Of The Netherlands V. Russian Federation) Tribunal Orders The Release Of The Arctic Sunrise And The Detained Persons Upon The Posting Of A Bond. 22 November 2013.

- Rezchikov, A., Trubina, M., (2018). SSHA nachinajut osparivat morkije prava Rossii. [The USA begin to dispute the sea rights of Russia]. Vzglyad. December 6, 2018.

- Rules of navigation in the water area of the Northern Sea Route. Aproved by the order of the Ministry of Transport of Russia dated January 17, № 7 (2013)

- Russian National Security Strategy Through 2020. (2009)

- Russian National Security Strategy. (2015)

- Soglashenije mezhdu Ministerstvom Rybnogo Khoziajstva SSSR i Khokkajdijskoj Assotsiatsijej Rybnykh Promyshlennikov o promysle morskoj kapusty japonskimi rybakami ot 25 fduecnf 1981 goda. [The Agreement between the Ministry of Fisheries of the USSR and the Hokkaido Fisheries Association on the gathering of the seaweed by Japanese fishermen. August 25, 1981.] Sbornik dvustoronnikh soglashenij SSSR po voprosam rybnogo khoziaystva, rybolovstsva I rybokhoziajstvennykh issledovanij, 1987, pp. 300-302.

- Summary of Recommendations of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in Regard to the Partial Revised Submission Made by the Russian Federation in Respect of the Sea of Okhotsk on 28 February 2013.

- The Federal Law №155 – FZ “On Internal Waters, The Territorial Sea And The Contiguous Zone Of The Russian Federation” (in edition of the Federal Law from 28 July 2012, N 132-FZ). (1998)

- The Federal Law of July 28, №132-FZ ” On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Concerning State Regulation of Merchant Shipping on the Water Area of the Northern Sea Route” (2012)

- The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation. (2016)

- The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation. (2014)

- The Protocol on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context to the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marineenvironment of the Caspian Sea. July 20, 2018.

- The Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and National Security up to 2020. (2013)

- Tkachenko, B. (2017). Teritorialno-pogranichnyj spor mezhdu Rossiyey i SSHA d Arktike I Beringovom more. [Territorial-border dispute between Russia and the USA in the Arctic and the Bering Sea]. Rossija i ATR. №2 (96), pp. 84-96.

- V Azovskomu mori zafiksovano zboji system navigatsii GPS (2019) . [Failures of GPS system are noticed in the Azov Sea]. Dzerkalo Tyzhnia. 7 March 2019.

- Wezeman, S., Kuimova, A. (2018). Turkey and Black Sea security. SIPRI.

- Zender, A. (2019). Can Russian submarines pass through the Turkish Straits according to the Montreux Convention? Beyond the Horizon, Commentary.

- Zykova, T. (2014). Okhotskoye more – nashe vse. [The Sea of Okhotsk – is our everything]. Rossiyskaya Gazeta. №60 (6332).

[1] History of the Russian-Norwegian territorial dispute in the Barents Sea, as well as the entire Arctic policy of Russia, originates from the Soviet decree in 1926, which relied on the right of Tsarist Russia, which contained the concept of sectoral lines, actually lines of longitude, Which comes from the extreme point of the land and crosses the North Pole. The sectoral principle of Arctic demarcation has never been supported by Norway. The dispute over the maritime boundary continued after 1957, when it was agreed on its first segment (through Varangerfjord) and lasted about 40 years.

[2] According to the commentary of former consul of Russia in Sapporo, Vasilia Safin, such a political promise was made in order for Japan to distance itself from the United States and achieve a neutral status for Japan, like Finland. Russia also used the dependence of Japan’s membership in the United Nations on the USSR’s consent and the position of a powerful Japanese fisheries lobby, which promoted the issue of compromise with Russia.

Contact

Phone

Tel: +32 (0) 2 801 13 57-58

Address

Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Davincilaan 1, 1932 Brussels