Introduction

Considering the retreats of ISIS from Mosul and Rakka, the expectations for the collapse of ISIS is rising but the crucial questions remain that need to be addressed.

In this article, we focus on explaining how weak states offer convenient environments for terror groups, and presenting policy options on the measures the international community could take to hinder the remnants of ISIS to operate in these states and prevent ISIS from re-emerging.

This article aims to provide recommendations for policymakers to help them address the root causes for the original birth of ISIS in order to preclude its re-emergence after its collapse. Even if the US and the other members of the coalition forces have been able to force ISIS to withdraw from the territories that it had previously captured, its legitimacy and the cause have not necessarily been undermined. Having been defeated in their territories, terror groups may look for new locations to operate in better conditions conducive to the group’s survival, especially when continuing to be present in the current location will lead to the organizational collapse. Considering the withdrawals of ISIS, it might look for new countries to relieve the pressure from the ongoing fighting, and might look for rebuilding its capacity to operate again. In this sense, we argue that weak states could be convenient places for ISIS for these purposes because the weak capacity of these states in maintaining law and order and managing border security might appeal to terror groups to re-invigorate its fighting and mobilization capacity.

Focus on North Africa, Central Asia and Middle East

Specifically, we argue that weak states in North Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan countries, Middle Eastern countries, and weak Central Asian countries might be suitable place for ISIS to rebuild its capacity to re-emerge. North African countries are important to consider because these countries have played key role for ISIS recruitment, and unstable conditions in some countries after Arab Spring, such as in Tunisia and Libya, might offer convenient environment for the remnants of ISIS to recruit jihadists from these countries for its re-emergence. We also pay attention to the Central Asian countries which have not drawn sufficient attention from academicians and policymakers even though the perpetrators of some recent terror attacks in Europe, including the terror attacks in Stockholm and Sweden, originated from the Central Asian countries. Based on the fact that the corruption rate in some of these countries is high, such as in Kyrgyzstan, and also the presence of Caucasus Emirate that acts as a branch of ISIS in North Caucasus, ISIS might use these countries to recruit people and rebuild its material strength for its re-emergence. Finally, since most counterterrorism operations against ISIS mainly concentrate on Syria and Iraq, ISIS may move to other weak Middle Eastern countries, including Yemen, Bahrain and even Turkey, in which there is considerably less military pressure on the terror group. Amongst those ones, Turkey is an interesting country which apparently fights ISIS on one hand, and on the other hand, the current Turkish government and president provided long-time sanctuary for ISIS agents and a useful corridor for the foreign fighters to transit to Syria and Iraq.

Organization of the Report

We have four additional chapters. In Chapter 1, we define the failed and weak states. We also explain the link between state failure and terrorism by drawing the insights from the scholarly literature. In Chapter 2, we revisit the existing suggestions provided by the previous studies to repair state failure, and give a discussion on the effectiveness of these suggestions. In Chapter 3, building on the existing literature, we provide our own recommendations for policymakers to keep the remnants of ISIS away from the weak states. We present four specific policy recommendations: providing foreign aid to weak states to strengthen their border control; developing and improving community policing; providing economic and political support to Islamic weak states for them to reform their religious education in a way that gain Muslims a flexible interpretation of Islam, which will eventually make Muslims much less prone to recruitment of radical terror groups. Finally, we also recommend the US and European policymakers to oversee where the aid money is being spent in weak states. More specifically, we suggest them to enforce the governments in weak states taking the aid money from the US and European states to spend it for counterterrorism purposes, and not for political causes. We provide more detailed explanations for these four specific policy recommendations in the fourth chapter.

Chapter 1

Failed States, Weak States and Terrorism

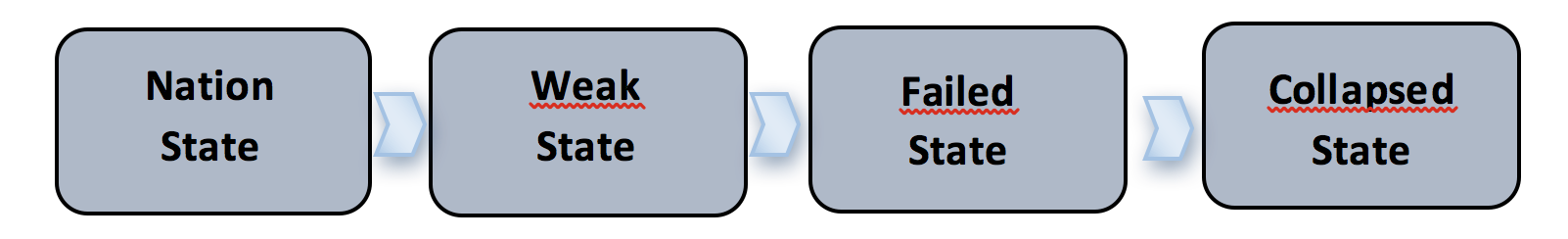

Weber (1919/1958) defines “state” as a human community that can claim the monopoly of the legitimate use of force within its sovereign border. This definition implies that states have varying degree of capacity in exercising their monopoly of the use of legitimate use of force. As the capacity of the state in projecting its authority erodes, declining state capacity might end up with a complete state failure over time. Figure 1 illustrates how declining degree of state capacity eventually leads to full state failure.

Figure 1 The Process of Complete State Failure with Declining State Capacity

Based on this preliminary conceptualization of state and state capacity, in the next section, we will give an extensive discussion on different forms of states which varying degree of state capacity as well as on the reasons underlying the erosion of state capacity. We start with failed states.

Failed States

In academic literature, many notions are used to name failed states. Rotberg (2003) describes failed states through shortcomings of the states. Nation states exist to deliver political goods – security, education, health services, economic opportunity, environmental surveillance, a legal framework of order and a judicial system to administer it, and fundamental infrastructural requirements such as roads and communications facilities – to their citizens. A failed state is no longer able or willing to perform the job of a nation state in the modern world. Failed states are tense, deeply conflicted, dangerous, and bitterly contested by warring factions. According to him, a failed state has following features: conflict, violence, civil unrest, communal discontent, dissent directed at the state, disharmony between communities, no control on borders, unable to establish security, growth of crime, flawed institutions, destroyed infrastructure, corruption, worsening GDP, economic chaos, lost legitimacy.

According to Rotberg (2003), a failed state has following features: conflict, violence, civil unrest, communal discontent, dissent directed at the state, disharmony between communities, no control on borders, unable to establish security, growth of crime, flawed institutions, destroyed infrastructure, corruption, worsening GDP, economic chaos, lost legitimacy.

In another article, Rotberg (2002) explains that failed states are unable to provide “political goods,” and describes a pattern of distinguishing features that failed states exhibit: government failure to maintain the essential wellbeing of their populations and/or governments that have begun to “prey upon their own citizens” through kleptocracy (a government or state in which those in power exploit national resources and steal; rule by a thief or thieves.); a sustained degradation of the infrastructure necessary for citizens to maintain a “normal” life, resulting in substantial humanitarian crises and/or migration; widespread lawlessness to the point that criminal groups act with impunity or rival the authority of government actors; and a transference of some or many citizens’ loyalties to non-state actors in many parts of the country (Piazza, 2008).

On the other hand, Hehir (2007) defines failed state based on the principle of sovereignty. . . a government that has lost control of its territory or of the monopoly on the legitimate use of force has earned the label [failed state].

The characteristics of failed states that are most commonly measured by scholars fall into four main categories. Those areas revolve around;

a. a nation’s capacity or willingness to provide internal security for its population along with an effective form of border control,

b. economic opportunity and prosperity,

c. political stability found in a government free of corruption,

d. a system of providing for the social welfare of its people by meeting basic human needs (Mechling, 2014).

Beyond this, there is an extreme version of failed state. Rotberg (2003) named this state in total failure as Collapsed State.

Relationship between States in Failure and Transnational Terrorism

After 9/11, international community began to see states in failure as places where terrorists were gathered, prepared and spread to the world. Officials, being aware of this fact, declared that international community could not continue to ignore the challenges posed by states in failure because their problems tended to spill across their borders, and a serious manifestation of this was increased transnational terrorist attacks (U.S. National Security Council 2002). US national security documents explicitly describe states in failure as, ”…safe havens for terrorists” (US National Security Council 2006).

In this respect, Rotberg (2002) hands over the responsibility to the wealthy big-power arbiters of world security. Making the world much safer by strengthening weak states against failure is dependent on the political will of those major countries. Otherwise it will continue to propel nation states toward failure and that failure will be costly in terms of humanitarian relief and post-conflict reconstruction. Ethnic cleansing episodes will recur, as will famines, and in the thin and hospitable soils of newly failed states, and thus terrorist groups will take root.

We have examined the political and intellectual approaches to the issues mentioned up to now. Are we sure that there is a real link between terrorism and states in failure?

Are we sure that there is a real link between terrorism and states in failure?

Some academics claim that the relationship is not clear. According to Hehir (2007), state failure by itself does not attract or breed terrorists and the attractiveness of a state as a locus for terrorists is contingent on a specific coincidence of variables. In his study, he compares the Failed State Index with not only the number of foreign terrorist organizations but also incidents and fatalities in the countries under the view of security of US nationals or the national security.

Piazza (2008) has researched the same topic and in contrast he has proved that there is a relationship between terrorism and states in failure in his analysis. He argues that states plagued by chronic state failures are statistically more likely to host terrorist groups that commit transnational attacks, to have their nationals commit transnational attacks, and are more likely to be targeted by transnational terrorists themselves.

Piazza bases this research on the tables he created with the data of the independent organizations. Firstly, he focuses on the incidents of transnational terrorism (MIPT database) by failed state index classification on a 1-year snapshot of data. It traces evidence of a significant relationship between state failure and transnational terrorism. Then he compiles the average aggregate state failure intensity indices [State Failure Task Force of the Center for International Development and Conflict Management (CIDCM) at the University of Maryland.] for 195 states for the period during 1991 to 2003 in order to review the situation over a longer period. He again finds out that the intensity of state failures is a significant, positive predictor of transnational terrorism. He also supports the hypotheses tested in his research with the results of the negative binomial models.

Piazza emphasizes that countries beset by significant state failures are more likely to be the source and target of transnational terrorism regardless of their regime type, size, age, level of economic development, degree of ethno-religious diversity, and whether or not they are experiencing an international war.

Today, it is certain that this relationship exists. Mechling (2014) specifies that states in failure lack the structural and institutional infrastructure to address issues within their own borders. In addition to lacking the ability to look after the welfare of their own people, they do not possess the capability of providing internal security, which creates an environment conducive to harboring terrorist organizations. He gives the example of ISIS in this regard. ISIS has taken advantage of the security vacuum in Iraq created by US troop withdrawals, and political instability in Syria over the existence of Bashir al-Assad’s regime, in order to advance their brutal objectives.

Convenience of Failed States for Terrorist Organizations

Some of the characteristics of these failed states, including providing the opportunity for further action and enabling impunity, are attracting terrorists. Piazza (2008) explains why these states are easier for terrorist movements to penetrate, recruit from, and operate within;

a. Those groups with ambitions to launch transnational attacks, in particular, need more extensive logistical and training and, therefore, need relatively more autonomous space with less costs of law enforcement.

b. These states offer terrorist groups a larger pool of potential recruits because they contain large numbers of insecure, disaffected, alienated, and disloyal citizens for whom political violence is an accepted avenue of behavior.

c. They retain the “outward signs of sovereignty” (Takeyh and Gvosdev 2002, 100).

(1) The principle of state sovereignty places legal limits on intervention by other states,

(2) These states are sovereign and legally recognized states, and so their government officials, who are often underpaid, poorly trained and monitored, and are therefore highly corruptible, they may help terrorists in exchange for money, political support or physical protection.

After this phase, it will be necessary to focus on which states offer the environment for the terrorists to operate easily. After Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda was in search of a new country to settle in. Everybody expected that Al-Qaeda’s most likely future destination would be Somalia, but that was not the case. According to Menkhaus (2003), the claim that Somalia hosted terrorist camps was repeated so often by government officials and media pundits that it became gospel, despite the absence of credible evidence that such a threat existed in Somalia. The environment assumed to be most attractive as a safe haven for al-Qaeda was, for some reason, not. Menkhaus presents the reasons, why areas of state collapse such as Somalia are not so attractive as safe havens, under four bullets:

a. In zones of complete state collapse, terrorist cells and bases are much more exposed to international counter-terrorist action.

b. Areas of state collapse tend to be inhospitable and dangerous, meaning few if any foreigners choose to reside there.

c. The lawlessness of areas of state collapse may reduce the risk of apprehension by a law enforcement agency, but it exponentially increases vulnerability to the most common crimes of chaos – kidnapping, extortion, blackmail, and assassination.

d. External actors(terrorists) find zones of endemic state collapse and armed conflict a notoriously difficult environment in which to maintain neutrality.

Weak States and Terrorism

As mentioned earlier, terrorist organizations cannot find the environment they need, in the states in total failure. For this reason, they prefer weak countries that can meet some basic needs, while providing protection against international counter-terrorism efforts at the same time. Stewart Patrick suggests a unique idea in that “truly failed states are less attractive to terrorists than merely weak ones.” He continues this point further by explaining that: while anarchical zones can provide certain niche benefits, they do not offer the full spectrum of services available in weak states. Instead, failed states tend to suffer from a number of security, logistical, geographic, and political drawbacks that make them inhospitable to transnational terrorists. (Mechling, 2014)

Truly failed states are less attractive to terrorists than merely weak ones

Hehir (2007) argues that modern international terrorist groups require access to functioning communication lines and thus states lacking infrastructural capacity are patently unattractive. Additionally, failed states, while generally characterized by a lack of effective central authority, are often host to heavily-armed warring factions and pose obvious risks even for international terrorists.

Menkhaus (2003) explains the reasons why weak state (quassi-state in his article) is repeatedly preferred over the zone of complete state collapse as a base of operation, a lair for evading detection, and a setting for terrorist attacks:

a. Governments, however weak, enjoy and fiercely guard juridical sovereignty, forcing the US and key anti-terrorist coalition allies into awkward and not entirely satisfactory partnerships with those governments in pursuit of terrorists. Information-sharing in such a setting can quickly lead to leaks, failed missions, and the danger of compromising informants.

b. Weak states play host to a large foreign community – diplomats, aid workers, businesspeople, teachers, tourists, missionaries, and partners in mixed marriages, among others. That gives foreign terrorists a decisive advantage in their ability to move about and mix into the society without arousing immediate attention.

c. Weak states generally feature very corrupt security and law enforcement agencies, but not such high levels of criminality that a terrorist cell is especially vulnerable to lawless behavior. Bribes to police, border guards, and airport officials allow terrorists to circumvent the law even while they enjoy a certain level of protection from it.

As understood from these studies, weak states are one of the main areas of preference for terrorists. This does not mean that terrorist activities in other countries are unlikely. Terrorists will always be active everywhere they find an opportunity.

Chapter 2

Revisiting the Previous Suggestions for Repairing State Failure

Up to now there have been evaluations of states in failure and we tried to make inferences about how they could become a haven for transnational terrorism. In the direction of the data obtained, it was precisely determined that states in failure provided the conditions required for terrorist organizations. The international community will not feel safe and secure unless the factors that cause the relationship between states in failure and transnational terrorism are removed. For this reason, this chapter will focus on the actions that can be taken to neutralize this relationship.

As Mechling (2014) insisted in his study, by supporting nations-at-risk on the front end, we can avoid forcing ourselves into decade-long counter-insurgencies as a result of our failure to prevent transnational terrorist groups from establishing firm roots in their desired areas of operation from the start. That is the basic point. International community should always be preemptive and must take the necessary measures.

Nation-building comes to mind as the first way of getting rid of failed states. According to Crocker (2003), nation building evokes efforts at economic development, political “modernization,” and democratization. A wide range of organizations and governments already work to help failing states undertake such measures as power-sharing and wealth-sharing among units and regions, constitutional and electoral engineering to give voice to cultural and ethnic minorities, and community-based projects to foster inter-communal healing and religious reconciliation. Once target states are selected, the major powers and institutions should focus their resources in four areas:

a. defusing civil conflict,

b. building state institutions,

c. protecting the state from hostile external influences,

d. managing regional spread.

In the meantime, some of the measures mentioned above are more effective. Basouchoudhary and Shughart (2007) find that it is economic freedom and secure property rights that reduce the number of terrorist attacks by source countries, rather than political rights (Azam and Thelen, 2008). They mostly focus on economic perspective but fighting with the ideology is missing in these studies.

From a local government point of view, they face another choice related to the method to deal with it; stick or carrot. Frey (2004) argues that the government is facing a tradeoff between using repressive counter-terrorism measures (“the stick”) and relying on more social spending for reducing the social support to the terrorists (“the carrot”). More militant groups might care less for social support, especially if they have external sponsors (Siqueira and Sandier 2006), thus pushing the government to choose more repressive methods.

Krasner and Pascual (2005) mention conflict prevention as the main issue in their article “Addressing State Failure”. However, there can be found some important clues for stabilization of failed/failing states inside. They insist on S/CRS (U.S. Department: the Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization) whose mission is to anticipate, avert, and respond to conflict. They explain the tasks of the office as;

a. develop both the framework and the capability to plan for stabilization and reconstruction.

b. make sure that the government(s) is(are) ready to move rapidly to help countries in the aftermath of conflicts.

c. assess and fill gaps across government(international) agencies in contracts and more informal arrangements with organizations that specialize in various aspects of stabilization and reconstruction (need funding).

d. establish new management mechanisms that will foster interagency cooperation.

e. coordinate stabilization and reconstruction activities between civilian agencies and the military.

f. cooperate more effectively with international partners.

This is the case for US. What about the international community? These efforts have to find grounds internationally. There are many organization in global arena that may have the responsibility or we can establish one.

The authors recommend four phases to manage post-conflict engagements effectively. They may also be implemented to failed/failing states:

a. Stabilization requires taking immediate action.

b. The conflict’s root causes must be addressed.

c. Laws and institutions of a market democracy must be created in order to foster the “supply side” of governance.

d. Civil society must evolve, communities need to develop as constituencies that call for political attention for their needs.

States in failure have economic difficulties and they are in search for the aid of wealthy states. Azam and Thelen (2008) explains this situation with a story from the past. Many foreign rulers of the past have used various means for protecting their interests abroad by inducing local regimes to act on their behalf. The most illuminating example is probably given by the Republic of Venice, which built a trading empire in the Mediterranean world in the late Middle Ages, between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries, while delegating to local rulers, and in particular the Byzantine Emperor, the task of protecting its traders by providing gifts and other incentives. The rich countries of the modern world have walked in their footsteps, on a much larger scale, coining the expression “foreign aid” as the name given to the underlying flow of gifts and presents.

At the end of their article, they suggest that Western democracies, which are the main targets of terrorist attacks, should invest more funds in foreign aid with a special emphasis on supporting education. In another article, Azam and Thelen (2012) added military intervention to foreign aid as the main counter-terrorism measure. Besides, according to the empirical results of Young and Findley (2011), foreign aid decreases terrorism especially when it is given to improve education, health, civil society and conflict prevention.

Systematic grouping of suggestions:

Efforts to ensure normalization of failed states should be coordinated by an international organization such as S/CRS, organized within the framework of the nation-building, and acted upon immediately. As a result of the recommendations in the previous section, it is possible to classify efforts that should be applied to failed states as follows:

a. Political

(1) political modernization, and democratization as an end state

(2) power-sharing among regions

(3) addressing to root causes

(4) defusing civil conflict

(5) protecting the state from hostile external influences

(6) managing regional spread.

b. Economic

(1) foreign aid

(2) economic development assistance

(3) economic freedom

(4) secure property rights

(5) wealth-sharing among units and regions

c. Social

(1) supporting civil society

(2) community-based projects implementation

(3) social spending

d. Administrative

(1) interagency cooperation institutions (such as S/CRS in international level)

(2) building state institutions

e. Legal

(1) constitutional and electoral engineering

(2) creation of laws

f. Military

(1) repressive counter-terrorism measures

(2) military intervention

Debate on the Effectiveness of the Suggestions

At the beginning of the measures to be taken for the terrorists to settle in states in failure, it was emphasized that these efforts should be coordinated through an international organization. Crocker (2003) argues that the United States and other leading powers need to plan and coordinate their strategies for dealing with failed states more coherently, fund key programs more generously, and speak more openly and directly about how to strengthen states and why it matters to do so. He adds international institutions may take the responsibility to coordinate.

Despite the fact that there are many organizations to coordinate and cooperate around the world, the effectiveness of international organizations is limited due to the fact that not all of the member countries consent at the time of crisis. The role of UN at the beginning of Iraq and Syria crisis can be given as an example. Unfortunately, all countries have their own interests and it is not easy for them to be guided for a common purpose.

Despite the fact that there are many organizations to coordinate and cooperate around the world, the effectiveness of international organizations is limited due to the fact that not all of the member countries consent at the time of crisis.

Without an international interagency cooperation institution leading all such activities, it seems difficult for the efforts to progress and succeed in the desired direction. Who will plan and execute the nation building efforts without such a structure? Do we really want to throw away our resources?

Until now, the nation building efforts applied to states in failure have not really achieved the desired result. There has been an improvement in their condition. But they have not turned into a real democracy. After a while, old harmful habits in these countries have relapsed and resistance to change has begun to be seen somehow. As long as the countries do not have a desire and effort from their own, it is only an illusion that states in failure reach the level of contemporary civilizations with an external intervention.

Just like this, major powers consider using military intervention to shape failed states. Following the interventions so far, we have witnessed how interventionists plan to rescue their troops from this swamp. In fact, a successful military intervention must rescue that state from its current state. But this has not been achieved until now. Azam and Thelen (2012) assert that military intervention in a country is only effective against the export of terrorist attacks when that country is located far enough from oil-exporting countries. When it is considered that the most problematic countries are close to oil-exporting countries or from another point of view, problems arise in the oil-producing regions; if this criterion is effective, we can reach the result that many military efforts will suffer in the field. And contrary to the expectations, a strong presence of foreign actors (like foreign troops) is counter-productive and they seem to be a strong attraction factor for terrorists.

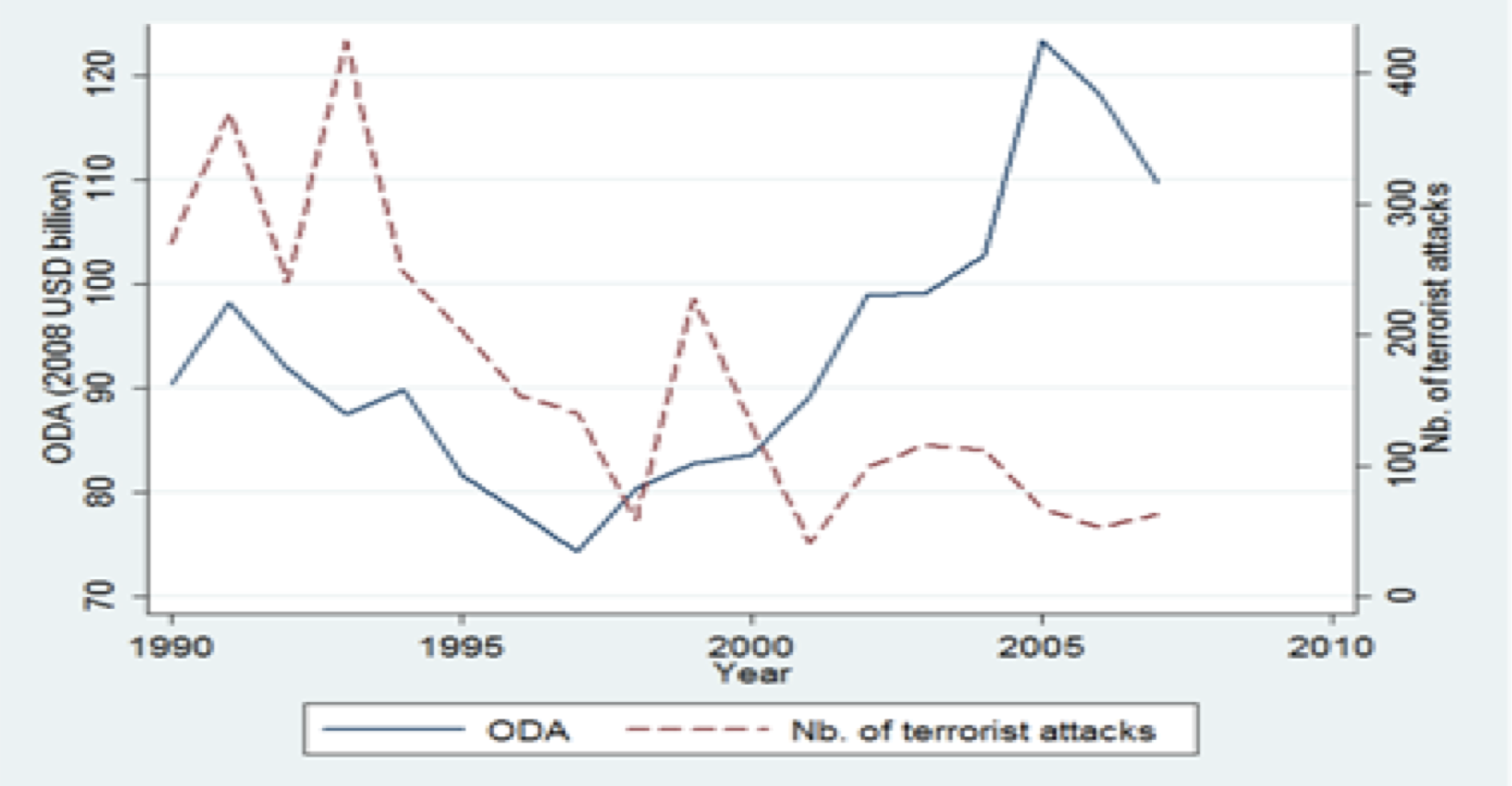

One of the most important external intervention method is foreign aid. Azam and Thelen (2008) found that aid can be pretty effective when it is used for education. The first decade of the 21st century has witnessed a major change in international relations, with the fight against terrorism becoming the dominant issue. At the same time, developed nations have massively stepped up their disbursement of foreign aid to poor countries, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Foreign Aid and Number of Terrorist Attacks, 1990-2007

Source: Azam, J. and Thelen V. (2012). Where to Spend Foreign Aid to Counter Terrorism, Toulouse School of Economics Working Paper Series 12-316.

Azam and Thelen used only secondary school enrollment rates as numerical data on education in their studies. In addition, a simple reading of the results, Bloom (2005), Reuter (2004) and Stern (2003) would suggest that such a wealth and education exert a positive influence on the decision to engage in terrorist attacks.

In contrary, aid to the Palestinian government increased in the last decade and there appears to have been a similar increase in terrorism related deaths against both Israelis and Palestinians, suggesting a reaction against the Western support (Stotsky 2008).

Young and Findley (2011) do not agree that foreign aid should only be used in the field of education. According to their research, foreign aid can reduce terrorism if targeted towards the appropriate sectors like education (but not only this one), conflict prevention/resolution on terrorism, health, governance, and civil society. However, in the cases of budget assistance and agriculture aid, they couldn’t find a significant relationship.

Although academics recommend to use it in different domains, it is not possible to check that the beneficiary states use foreign aid in the required areas due to problems in functioning of state institutions. Again, the use of the aid in a beneficial way is proportional to the efficient operation of the domestic system. If all the levels within the state are not operated as needed, it is inevitable that the aid will be wasted.

Until now, we have seen how the efforts for the failed states have been ineffective. Beyond that, we face a bigger problem. Academic reviews only deal with countries that have failed or are in a position close to being failed. Weak states with structural problems are out of sight. Crocker (2003) insists on this problem. A wide range of organizations and governments already work to help failing states, but weak states also need greater administrative and governing capabilities, if they are to behave as responsible, sovereign actors, including enhanced legal codes and court systems; upgraded local and regional administrative apparatuses; responsive and well-trained police forces; stronger bank oversight and public financial management; and closer ties between isolated financial, security, and intelligence personnel at home and abroad. We’ll focus on useful policy recommendations in next chapter.

Chapter 3

Developing Effective Strategies to Forestall the Re-emergence of ISIS in Failing States

Earlier chapters focused on international efforts in order to improve the situation in states in failure and protect them from being the target of transnational terrorism. In general, it can be seen that the efforts have a structure that can be effective in the long run, and that they cannot be implemented for a long-time due to rapid developments in the international conjuncture. In this chapter, we will focus on the possible courses of action for the terrorists and target countries by examining the EU and the US perspectives, the current practices will be reviewed and the measures that can be effective in the short term will be suggested.

Next Haven of ISIS?

It is still unclear whether or not ISIS militants will abandon Iraq and Syria after being defeated. It is also not known which countries they will go to if they decide to leave. However, some evaluations are made in this regard. In a recent one, Clarke (2017) reveals three possibilities:

a. The “hardcore fighters” will likely remain in Iraq and Syria and look to join whatever the next iteration of the devolving group may be.

b. A second group of fighters are the potential “free-agents or mercenaries,” who will travel abroad to take part in the next jihadist theater, whether it be in Yemen, Libya, the Caucasus, West Africa, or Afghanistan.

c. Third group of foreign fighters may attempt to return to their countries of origin.

As seen above, two groups are expected to go to other countries. These terrorists will probably choose primarily their homeland or weak states in order to resume their activities from where they left off.

Many weak countries around EU can be evaluated in this context if we take into account the number of ISIS foreign fighters by country (Benmelech and Klor, 2016), the effectiveness and new tendencies of recruitment activities (Botobekov, 2016), and the risk levels of countries falling to failure. In light of the criteria given above, ISIS might find suitable environments in North Africa, especially Sub-Saharan countries, some countries in Central Asia, especially those having high corruption rates, such as Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, and some weak states in Middle East, such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain, and even Turkey which has an administration tolerating ISIS’s activities and has a rapidly declining economy and military.

Policy Recommendation 1: Effective Border Management

According to the experiences obtained from Iraq and Syria, it is much more difficult to get rid of these terrorists once they have settled in a region. For this reason, we should first focus on the measures to prevent terrorists from entering borders. Border control measures need to be implemented effectively in countries where ISIS could come in sight. First of all, it is necessary for all countries to use their own security forces and resources appropriately in this direction.

Usually border control elements in the weak states do not fulfill their tasks effectively. Depending on whether these elements are civilian or military, effective control cannot be provided due to lack of equipment and coordination, or human rights violations are caused by strict applications. The only way to solve this problem is to think about deploying gendarmerie elements on the border if they exist in the country. According to Lutterbeck (2013) gendarmerie‐type forces, as opposed to civilian‐style police, play a predominant role in border, due to their hybrid nature and the heavier equipment at their disposal. Moreover, the centralized and hierarchical structure of gendarmeries – a typical feature of military organization – may make them more suitable for operating over the vast and open spaces involved in border control. Of course, it is not enough to have only these forces. In order to use these and similar units in a harmonious way, standards of procedures, trained personnel and equipment are necessary. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) is a good example of the institutions to promote, coordinate and develop border management.

Frontex was first established with the name “European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union” in 2004. While regular border control is the exclusive responsibility of the Member States, Frontex’s role focuses on coordination of deployment of additional experts and technical equipment to those border areas which find themselves under significant pressure. Frontex also builds the capacity of the member states in various areas related to border control, including training and sharing of best practices.

During implementation, border guards and technical equipment are deployed to the operational area and carry out their duties according to the operational plan. Guest officers have capacity to perform all tasks and exercise all powers for border checks or border surveillance in accordance with Schengen Borders Code. Once completed, each operation is evaluated by Frontex, the participating countries and other stakeholders involved ensuring that the operational process is constantly refined (Frontex Official Site).

According to External Evaluation Report (2015), Frontex’s operational activities were assessed to positively contribute to the improvement of integrated management of the external borders of the Member States (MS), by having a positive impact in reinforcing and streamlining cooperation between MS’s border authorities and thereby improving the coordination and effectiveness of MSs border management activities. Report concludes that the Agency has been most effective in provision of assistance to Member States’ training of national border guards. Activities of Frontex have contributed to improving the capacity of European border guards, to improving the access to relevant technical and human resources for operations at external borders, and to improving the knowledge and development of technical equipment for border surveillance and control. With these capabilities, it dictates that Frontex may train border guards from third countries properly.

Frontex also has the permission to cooperate with the third-party countries. Currently, it has 17 agreements with the third-party countries and two with the regional organizations whose membership is made up of third countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia, Canada, Cape Verde, Commonwealth of Independent States, Georgia, Macedonia, MARRI, Moldova, Montenegro, Nigeria, Russia, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, USA. The agency is planning to sign working arrangements with eight other countries, according to the ‘Single Programming Document 2016-19’. These countries are Brazil, Egypt, Kosovo, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Senegal and Tunisia (Jones, 2017). Among these countries, some of them may be considered to be the places where ISIS militants can be settled in the future. However, these agreements are more superficial and might include limited issues. They do not have a holistic approach to border management. Unfortunately, without this kind of a holistic mission, the efforts may be wasted in weak states.

Figure 3: Overview of the current EU mission and operations

Source: Official Site of European External Action Service (EEAS)

At this point, we can have a look at the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) Mission of EUBAM Libya which was initially launched in May 2013 as an integrated border management mission in Libya (EU-Libya Relations Factsheet, 2017). Frontex is contributing to the Mission with its expertise in border management. The Mission and Frontex jointly designed the law enforcement training curricula for Op Sophia’s training of the Libyan coastguard and navy. Frontex also provided a tailored monitoring (map) application for situation monitoring purposes. In addition, advising on the possibilities for cross-border cooperation (Libya-Niger) is being further explored in coordination with EUCAP SAHEL Niger, EUCAP SAHEL Mali and Frontex, where and when possible, including on exchange of information of migrant flows, smuggling networks and lessons learned (Strategic Review on EUBAM Libya, EUNAVFOR MED Op Sophia & EU Liaison and Planning Cell-15 May 2017). Even though Libya may be accepted as the second castle of ISIS, Frontex plays an active role hereand its efforts are predicted to increase day by day. As such, it provides clues that it will properly carry out the activities for the improvement of border management in other countries.

CSDP missions/operations and Frontex can clearly be mutually reinforcing. But some of the researchers think that a CSDP mission is ideally part of a comprehensive approach in which also the ‘root causes’ of conflicts are addressed, while Frontex activities are geared towards managing the effects of conflicts. The involvement of Frontex in CSDP operations can endanger the EU’s comprehensive approach in crisis management (Drent et al. 2013).

It is not possible to say their opinion is wrong. The use of Frontex outside the EU’s external borders can cause problems in the existing system, but ‘world is more flat’ than it was in the past (Friedman, 2005). If we do not give importance to these weak states, if we do not help them, we will see the effect of the problems here on the mainland. With that in mind and in the direction of the topics discussed under border management up to now, in order to augment and to add value to border control activities of the Weak States:

a. Weak states shall deploy hybrid elements such as gendarmerie on the border if they exist in the country.

b. Frontex experts should be deployed to the countries where ISIS is likely to be settled,

c. These experts should review the existing system and advise agencies on border management, especially on such topics as intra and inter-agency cooperation, risk management methods, optimal use of existing equipment, restructuring of agencies to increase effectiveness and best practices.

d. Border guards and other relevant staff shall be trained on the spot and some of them shall be sent to Europe to reach common training standards of EU.

e. The experts should assist technical and operational cooperation with other countries.

f. During all these activities, the necessary precautions should be taken in order not to cause problems in the EU borders, as Frontex experts are deployed abroad.

Policy Recommendation 2: Community Policing

Initially, it would be the primary goal to prevent transnational terrorists from crossing border and entering a country. If this cannot be achieved, what measures should be taken to prevent terrorists from becoming effective?

It should be based on a system that can be effective in the short run and can be implemented with existing tools. At this point, community-based counter-measures should be foreground. The results from Australia show that, in the context of community-based approaches to counterterrorism, there are actions and approaches that police can adopt to improve relations with the concerned community and increase their cooperation in efforts to tackle terrorism (Cherney and Murphy 2016). According to Lambert and Parsons (2016), individuals in communities and neighborhoods where terrorist movements seek recruits and supporters are often more likely to help police identify and disrupt terrorist conspiracies if they are treated fairly. The particular advantages of this kind of community policing are that it provides local communities with a degree of collective influence over how they are policed and that, in acting to address locally defined problems, neighborhood officers are well placed to generate trust and collect community intelligence (Innes 2006). It would not be wrong to claim that community policing is effective against terrorism when mutual trust is established.

Several scholars have observed that community policing strategies developed in the ordinary crime control context can be transferred into the terrorism context. Although the scope and ambitions of ordinary community policing are hotly contested, one strand of that strategy focuses on police measures to encourage members of a pertinent community (defined in geographic terms) to share information with the police, and to participate in collaborative problem-solving exercises (Huq 2016). Community policing forms partnerships between law enforcement and communities and emphasizes proactive joint problem-solving so as to build trust and cooperation and address the conditions that mitigate public safety. Research studies of community policing in other situations have shown that it usually improves citizens’ satisfaction with and trust in the police (Weine et al. 2017).

Lambert and Parsons (2016) argue that the practitioners of community based counterterrorism policing are not just police officers but also civil servants operating at both national and local levels, teachers, and nongovernmental organizations. But Huq (2016) opposes that they are two different concepts. He also accepts that non-state actors embedded in geographically and religiously defined communities have a distinctive role to play in responding to growing terrorist recruitment efforts in Europe and North America but he is naming this type of efforts as community-led counterterrorism. The central way in which it differs from community policing against terrorism is the primacy of non-state actors over state actors. But he adds that the community-led variant presents delicate normative challenges and risks large potential costs.

It would be more appropriate to use the existing police elements in order to be able to quickly start implementing. As a result of their study of how the implementation should be done, Weine et al. (2017) identified five community policing practices:

a. Engage : Community outreach officers meet and establish one-on-one relationships with community leaders to open communication channels. They also build partnerships with community-based organizations, including faith-based and interfaith organizations.

b. Build Trust : Community outreach officers work to establish honest and open dialogue on sensitive issues with community leaders and members, such as concerning terrorism, hate crimes, and discrimination. They acknowledge and promote mutual understanding of communities’ historical traumas and their present needs and strengths. The officers aim to be as transparent as possible regarding crime fighting and police conduct.

c. Educate : Community outreach officers teach communities about crime (including hate crimes), police work, and community resources to combat criminal activity. This includes building knowledge and awareness in communities about violent extremism and how to prevent it.

d. Problem Solve : Community outreach officers help communities and individuals respond to their current problems. This includes helping communities respond appropriately to Islamophobia, discrimination, and hate speech and crimes. They also help community members access available resources to address social, legal, and mental and physical health concerns. They provide communities with knowledge and skills to assess the threat level of individuals and educate them on how to respond.

e. Mobilize : Community outreach officers promote the civic engagement of community members, including promoting women and youth advocacy on civic and public safety issues. They assist immigrants and refugees in promoting their integration and addressing their security concerns. They also provide community-based organizations with consultation, materials, information, and support regarding how their organization can contribute to building resilience to violent extremism.

Weine et al. (2017) insist that adopting a community policing model is a necessary approach to better protect and serve communities at risk for violent radicalization. As Ian Blair expresses his learning from extensive experience in regard to counterterrorism policing and Muslim communities: “I just think we have to be incredibly careful, we shouldn’t be doing this to the community, we should be doing this with the community.” (Lambert and Parsons, 2016).

If we want to prevent the terrorists from becoming active in the weak states, we should educate the police in these countries to use community policing methods. In this regard, it will be possible to establish and maintain true partnerships between police and communities, and the established trust environment will prevent the settlement of terrorists.

Policy Recommendation 3: De-radicalizing Religious Education in Muslim Weak States

One of the most important recommendation for the policymakers to prevent the re-emergence of ISIS in the future is to invest in improving religious education in Islamic countries, especially those from which ISIS find recruits, such as Tunisia.

One of the most important recommendation for the policymakers to prevent the re-emergence of ISIS in the future is to invest in improving religious education in Islamic countries, especially those from which ISIS find recruits, such as Tunisia.

Even though there is nothing inherent in any religion or culture that either encourages terrorism or prevents it from motivating violence (Ginsburg and Megahed 2003), the fact that ISIS or ISIS-type transnational terrorist groups can find recruits from different Islamic countries indicates an unfortunate reality that there is a serious problem with the internalization of Islamic principles by Muslims. Furthermore, considering the fact that suicide terrorism is one of the major tactics used by terror groups advocating radical interpretations of Islam, like ISIS, but committing suicide is strictly forbidden in Islam, Muslims supporting or participating in such terrorist groups also have lack of basic knowledge about the rules in Islam. Not all Muslims can read Arabic scripture of Quran, and the majority of them do not know the meaning of the sentences in Quran. Therefore, they usually rely on the guidance of religious scholars ((Fair, Goldstein, and Hamza 2016; Wiktorowicz 2005). ISIS, Al-Qaeda or other radical groups exploit this knowledge and the internalization gap by appealing to small minority of Muslims and establishing moral authority over religious matters (Ciftci, O’Donnel and Tanner 2017). This small minority of Muslims favors the literal interpretation of religious texts, and they may find these radical terrorist group’ literalist interpretation of Islam and their justification for using violence to implement sharia law persuasive (Cifci, O’Donnel and Tanner 2017). The empirical results of Ciftci et al.’s (2017) study show that people favoring literalist interpretation of Islam are more supportive for militancy than those having flexible approach.

[

Our first recommendation regarding improving religious education, in this sense, is to help weak Islamic states to provide religious education to Muslims that integrate their reflective thinking skills and intercultural understanding. More specifically, these Islamic countries should offer a religious education to Muslims that can enable them to have a contextual understanding of Islam and its contextual expressions.

Islamic countries should offer a religious education to Muslims that can enable them to have a contextual understanding of Islam and its contextual expressions.

Being informed by the contextual expressions of Islam will allow Muslims to develop flexible interpretation of religious texts, and undermine the literalist interpretation of Islam among Muslims. As Muslims in these countries have flexible approach in interpreting their religion, the chance of radical terrorist groups to find recruits from those Muslim societies will dramatically reduce since As Ciftci et al. (2017) suggest, these radical groups rely on literalist interpretations of religious texts. Such an approach in improving religious education in these countries might even be used to rehabilitate the fighters of ISIS when they returned to these weak Islamic countries after ISIS has been defeated. By taking such a religious education, Muslims living in these weak Islamic states might be better informed about Islam, and challenge the radical interpretations of their religion.[1] In this way, the propaganda activities by the remnants of ISIS in these weak Islamic countries will fail because the justification for using violence against innocents will not find support among Muslims who expose such a religious education.

Our second recommendation for policymakers is that in helping weak Islamic countries to improve their religious education system, Western countries might want to allocate more resources to Muslims educators to teach proper understanding of some critical concepts in Islam.

Western countries might want to allocate more resources to Muslims educators to teach proper understanding of some critical concepts in Islam.

While the general lack of knowledge about Islam constitutes a serious problem that needs to be solved, we also argue that radical terrorist groups like ISIS might be more likely to exploit the misunderstanding about some particular concepts in Islam among Muslims, such as martyrdom, jihad and the use of violence. According to Al-Badayneh’s (2011) study on 190 students from Mutah University in Jordan, martyrdom, violence, hatred and jihad are ideas that radical beliefs are mostly concentrated. Providing proper understanding of these concepts to Muslims in these weak states, in this sense, bears a crucial importance to hinder radical terrorist groups to capitalize on the confusion of some Muslims in order to recruit them. The financial resources might be concentrated to religious teachers/Muslim educators teaching these concepts to Muslims. Given that even these terms are debated among religious scholars, the training of religious teachers/Muslim educators might also be useful to teach the proper meanings of these important concepts. When Muslims distinguish martyrdom from committing suicide and learn that the killing of the innocent people and even animals are forbidden in doing jihad, they will be much less prone to the propaganda of radical terrorist groups, and these Muslims will be more likely to reject participating in these extremist groups.

Our final recommendation to improve religious education in the weak Islamic countries is to support reforming madrassah schools. Madrassah schools have a significant place in religious education in some Islamic countries, and these schools have been discussed recently since they might be the center of extremist interpretation of Islam, and facilitate terror groups to recruit people from these schools.

Madrassah schools have a significant place in religious education in some Islamic countries, and these schools have been discussed recently since they might be the center of extremist interpretation of Islam, and facilitate terror groups to recruit people from these schools.

The US pressured Pakistan to reform these schools but there was a resistance from madaris elites against reforming madaris institutions. We recommend the policymakers in Europe and the US to provide financial support to the weak Islamic countries to reform madrassah-type schools in order for these religious schools not to promote extremist thoughts but provide a religious education that holds a flexible approach in interpreting Islam. In addition, the policymakers should also give political support to the politicians who want to reform these schools in these weak states because the establishment in these schools may prevent such reform movements as we see in the Pakistani examples. Providing political support to these politicians may help them undermine these religious elites to clear the path to reform madrassah schools.

Policy Recommendation 4: Discouraging Recipient States from Using Foreign Aid for Different Purposes

As the studies investigating the nexus between foreign aid and terrorism have suggested, providing foreign aid to the states from which transnational terrorism originates might lead to favorable outcomes in counterterrorism under some conditions, especially allocation of foreign aid to some specific sectors, such as education, civil society (Young and Findley 2011;Azam and Thelen 2012). In addition to this condition for the success of providing foreign aid in countering terrorism, another factor that might also affect the success of this strategy is to consider the recipient state’s domestic and foreign policy priorities, and prevent the recipient states from using aid for the purposes other than counterterrorism. Boutton’s (2014, 2016) quite recent studies suggest that the recipient country might use the aid for the purposes of fighting against its rival or regime consolidation, and therefore, these countries might not intentionally eliminate terrorists since doing so might endanger the future aid provisions. Some examples also confirm this argument. After 9/11, the United States has provided Pakistan over 10 billion dollars to combat Taliban and other terror groups in Pakistan (Boutton 2014) but since Pakistan’s primary concern after its independence has been to achieve parity with its rival, India (Paul 2014), some observers argue that Pakistan has used the considerable portion of the US foreign military aid for its military buildup in case of a future conflict with India, rather than defeating terror groups (Rashid 2008;Haqqani 2005). As we see in the Pakistani example, it is possible to see a different form of aid diversion during President Nouri Al-Maliki’s administration in Iraq. In the aftermath of the US withdrawal in 2011, Maliki administration used US counterterrorism funds to purge the dissidents, namely Sunnis, which eventually contributed to Sunni insurgency (Dodge 2012). Furthermore, such an aid diversion has led to the discrimination of Sunnis and contributed to the emergence of ISIS (Boutton 2016). This example from Iraq shows that providing foreign aid without considering the dynamics of domestic politics has generated unexpected outcomes, which is an emergence of a new deadly terrorist group.

In this sense, while we propose that foreign aid from the US and the European countries should be provided to weak states in which the remnants of ISIS might operate in the post-ISIS environment, specifically to improve religious education to discourage radicalism, we also provide an important caveat, suggesting that donor countries must consider domestic and foreign policy priorities of the recipient states.

Photo by Pixabay[/caption]

More specifically, donor countries should specify the conditions placed on aid packages, and show a clear signal that they will withdraw the aid and even sanction the recipients when the aid is used for the different purposes (Boutton 2014,2016). In this sense, the US and European countries should consider the rivalry relations and the concerns for regime consolidation in African countries in which the remnants of ISIS might operate. Considering territorial disputes and ethnic conflicts in some African countries, the donor countries should be highly aware of these problems, and quickly punish the aid diversion behaviors. The limitation of making such a proposition is that the donor countries are not fully capable in monitoring the recipient states’ efforts or aid diversion behaviors (Boutton 2016). In order to strengthen their monitoring capacity, they should improve relations with the recipient countries as many fields as possible. As their relations become closer, they will have more opportunities to monitor the extent to which the recipient country uses the aid money for counterterrorism purposes. Security cooperation, trade relations or joint educational initiatives might be some ways of improving relations with the recipient countries.

Conclusion

We have not yet witnessed that a state has declared support to terrorism. Normally, it is clear that no country will want to establish partnerships with such brutal killers. But there is a reality that terrorists do not have difficulty finding territories for themselves.

States should adequately deliver political goods to their citizens. If they cannot do so, their existence does not seem possible to be continued. They become a weak state and then inevitably fail or collapse. During the period of weakness, they offer the most appropriate conditions for transnational terrorism even if they are not very willing. Majority of the states around Europe may be counted in this category.

The international community has made great efforts to transform these countries into nation states. But it’s not as simple as it looks. Efforts cannot be claimed to be very effective: The establishment of an international interagency cooperation institution, nation building, military interventions, unmanageable foreign aids, etc. All of these tools were used to solve the problem, but it was not possible to fully recover the weak states through long-running applications. There is nothing else in the world that changes as fast as change. Today, it is impossible to catch up with the pace of events. Factors that lead to the decisions taken in the context of the situational assessment can become much more different just even one day after.

Under these circumstances, it is necessary to reach solutions that can achieve fast results. We should strengthen the borders of these countries so that transnational terrorists do not get in. Frontex experts are thought to be able to make useful contributions to border management of these countries. We should educate the police in these countries to use community policing methods. Establishing true partnerships between police and communities will prevent the settlement of terrorists. We should also invest in improving religious education in Islamic countries to teach the community proper understanding of contextual expressions and critical concepts in Islam and to reform madrassah schools. Finally, foreign aid should be allocated to be used in certain areas. We have to set up systems that may detect if governments use them for different purposes.

We, as international community, can cooperate against transnational terrorism, by focusing on proactive solutions that will yield results in the short term. In this way, we may make the world a more peaceful place.

By Mustafa Kirişçi, Non-resident Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon, PhD Candidate and Resul Mülayim

References:

Al-Badayneh, D.M. (2011). University under risk: the university as incubator for radicalization. In: I. Bal, S.Ozeren and M.A. Sozer, eds. Multi-faceted approach to radicalization in terrorist organizations. Amsterdam, NLD: IOS Press, 32–41.

Azam, J. and Thelen V. (2008). The Roles of Foreign Aid and Education in the War on Terror, Public Choice, Vol. 135, No. 3/4 (Jun., 2008), pp. 375-397. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27698274

Azam, J. and Thelen V. (2012). Where to Spend Foreign Aid to Counter Terrorism, Toulouse School of Economics Working Paper Series 12-316.

Benmelech E. and Klor E.F. (2016). What Explains the Flow of Foreign Fighters to ISIS? Retrieved from http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/benmelech/html/BenmelechPapers/ISIS_April_13_2016_Effi_final.pdf

Botobekov, U. (17 May 2016). ISIS and Central Asia: A Shifting Recruiting Strategy, The Diplomat. Retrieved 23 August 2017 from

http://thediplomat.com/2016/05/isis-and-central-asia-a-shifting-recruiting-strategy/

Boutton, A. (2014). “US foreign aid, interstate rivalry, and incentives for counterterrorism cooperation.” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 6 (2014): 741-754.

Boutton, A. (2016). “Of terrorism and revenue: Why foreign aid exacerbates terrorism in personalist regimes.” Conflict Management and Peace Science(2016): 0738894216674970.Fair, C.C., Goldstein J.S., and Hamza A. (2016). “Can Knowledge of Islam Explain Lack of Support for Terrorism? Evidence from Pakistan.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, April 2. doi:10.1080/1057610x.2016.1197692.

Cherney, A. and Murphy, K. (2016). Police and Community Cooperation in Counterterrorism: Evidence and Insights from Australia, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1253987

Ciftci, S., O’Donnell, B.J., and Tanner, A. (2017). “Who Favors al-Qaeda? Anti-Americanism, Religious Outlooks, and Favorable Attitudes toward Terrorist Organizations.” Political Research Quarterly (2017): 1065912917702498.

Clarke, C.P. (2017). The Terrorist Diaspora After the Fall of the Caliphate, The RAND Corporation, Testimony presented before the House Homeland Security Committee Task Force on Denying Terrorists Entry into the United States on July 13, 2017.

Crocker C.A. (2003). Engaging Failing States, 82 Foreign Aff. 32 2003. Retrieved from http://heinonline.org

Current military and civilian missions and operations of EU – EEAS. Retrieved 17 August 2017 from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/430/Military%20and%20civilian%20missions%20and%20operations

Dodge, T. (2012). Iraq’s road back to dictatorship.” Survival 54(3):147-168.

Drent M., Homan K. and Zandee D. (2013). Civil-Military Capacities for European Security, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael.

European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX). Retrieved 16 August 2017 from http://frontex.europa.eu

External Evaluation of the Agency Under Art. 33 of the FRONTEX Regulation Final Report (2015). made by SA, TM, MTHJ, IMN, TSVB, ANKB, Retrieved from http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/General/Final_Report_on_External_Evaluation_of_Frontex.pdf

Fair, C.C. (2008). The Madrassah Challenge: Militancy and Religious Education in Pakistan. Washington, DC: USIP Press.

Haqqani, H. (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Hehir, A. (2007). ‘The Myth of the Failed State and the War on Terror: A Challenge to the Conventional Wisdom’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1:3, 307 – 332

Hewitt, C. (1984). The effectiveness of anti-terrorist policies (p. 85N). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Huq, A.Z. (2016). Community-Led Counterterrorism, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1253988

Innes, M. (2006). Policing Uncertainty: Countering Terror through Community Intelligence and Democratic Policing, ANNALS, AAPSS, 605, May 2006.

Krasner, S.D. and Pascual, C. (2005). Addressing State Failure, Foreign Affairs. Jul/Aug2005, Vol. 84 Issue 4, p153-163.11p.1

Lambert, R. and Parsons, T. (2016). Community-Based Counterterrorism Policing: Recommendations for Practitioners, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1253989

Lutterbeck, D. (2013). The Paradox of Gendarmeries: Between Expansion, Demilitarization and Dissolution, The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces. Retrieved from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/173448/SSR_8_EN.pdf

Mechling, A.D. (2014). Failed States: An Examination Of Their Effects On Transnational Terrorist Organization Movements And Operational Capabilities (Thesis), Johns Hopkins University.

Menkhaus, K. (2003). Quasi-States, Nation-Building, and Terrorist Safe Havens, Journal of Conflict Studies, Vol 23, No 2 (2003)

Paul, T.V. (2014). The Warrior State: Pakistan in the Contemporary World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Piazza, J.A. (2008). Incubators of Terror: Do Failed and Failing States Promote Transnational Terrorism?, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Sep., 2008), pp. 469-488. Wiley on behalf of International Studies Association. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734247

Rashid, A. (2008). Descent into Chaos: The United States and the Failure of Nation Building in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia. New York: Viking.Rotberg R.I. (2002). The New Nature of Nation-State Failure – The Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The Washington Quarterly 25:3 pp. 85–96.

Rotberg R.I. (2003). Failed States, Collapsed States, Weak States: Cause and Indicators.

Weber, Max (1919/1958) Politics as a vocation. In: H H Gerth & C Wright Mills (trans.) From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Galaxy (77-128).

Weine, S. and Ahmed Y., Chloe P. (2017). “Community Policing to Counter Violent Extremism: A Process Evaluation in Los Angeles,” Final Report Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security. College Park, MD: START.

Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield.

Young J.K. and Findley M.G. (2011). Can Peace Be Bought? A Sectoral-Level Analysis of Aid’s Influence on Transnational Terrorism.

[1] The original idea for such an approach to improve religious education belongs to Abdullah Sahin, who is a reader in Islamic Education at University of Warwick, and he practiced this approach young British Muslims. See his article on the Guardian for more details. https://www.theguardian.com/profile/abdullah-sahin