By Angelo Jong, Ibrahim Genc, Joshua Saunders, Liseth Medina Vizcaino

Abstract

The Structural Synergies of Power (SSP) Method will be used in this global response strategy to explore the interlocking systems of power which have led to the creation of the Australian Government policy of processing unauthorised asylum seekers offshore in regional processing centres. Ramos (2017, p.1) has made it clear that the three ‘interlocking spheres of politics, culture and economics’ work to reproduce power. In this essay, these three factors that play significant role to shape Australia’s Offshore Processing of Asylum Seekers will be examined. These spheres of power produce ‘different modes of influence’ (Ramos 2017, p.5). More specifically, economic power ‘expresses influence through exerting wealth’, political power ‘expresses influence through enactment of policy and law’ and cultural power ‘expresses influence through mediating levels of legitimacy and shaping the public idea of good’ (Ramos 2017, p.5).

What is the Problem?

Under International law, Australia has non-negotiable obligations to protect and uphold the human rights of all asylum seekers and refugees’ who arrive in Australia, regardless of their mode of arrival. The Australian Government has obligations under a number of different international instruments which Australia has ratified. These include: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT); and the Convention on the Rights of the Child(CRC). Under international law, Australia has obligations to not send people to a third country where they would face violation of their human rights, these obligations apply to both refugees and asylum seekers (Australian human rights commission 2014, p.1). Australia has been criticised for outsourcing its asylum seeker and refugee obligations to other countries in the region including Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG) (Human Rights Watch 2016).

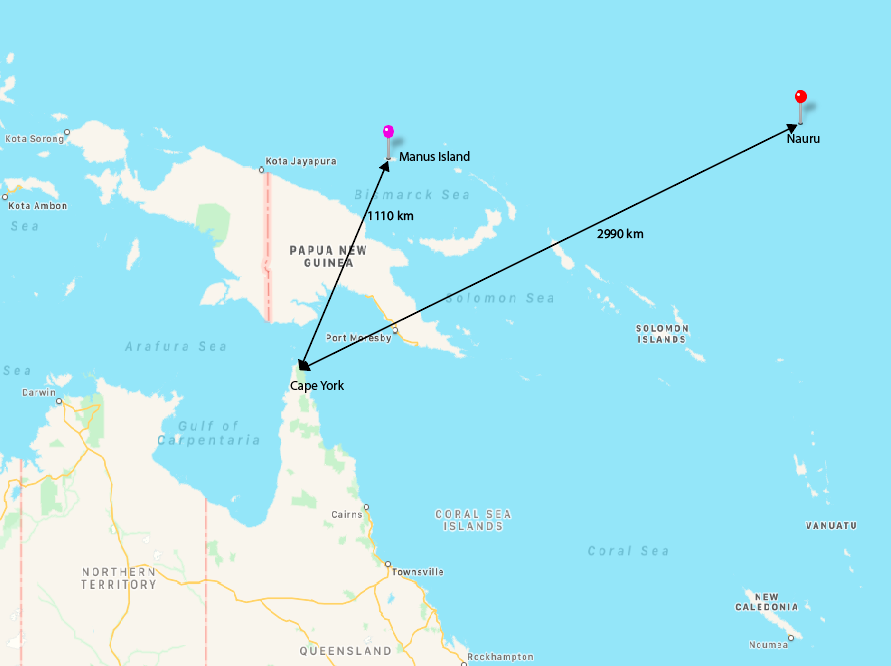

An asylum seeker refers to someone ‘seeking international protection but whose claim for refugee status has not been determined’ (Phillips 2015). The United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) defines a refugee as an individual who is outside their country of origin and unable to return due to a well-reasoned fear of being persecuted against on the basis of their race, religion, nationality, or association of a specific social group or political opinion (Australian Human Rights Commission 2014). Between December 2008 and 2014 more than 50,000 asylum seekers arrived in Australia by sea, with more than 860 recorded deaths at sea (Refugee Council of Australia 2017a). As a result, the Australian Government in 2012 established offshore processing centres in the Republic of Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG) with the agreement of the respective governments’ (Australian National Audit Office 2017). In April of 2017, 1194 people were reported to be in ‘Australian funded offshore processing centres’ (Refugee Council of Australia 2017a).

The Australian Government has failed to respect international standards and laws related to asylum seekers and refugees, most obviously, Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights(1966) (ICCPR). In 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture stated that Australia was in breach of the Convention Against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment(1984) (CAT) for ‘failing to provide adequate detention conditions [and] end the practice of detaining children’ (Human Rights Watch 2016, p.2). Green and Eagar (2010, cited in Newman, Proctor & Dudley 2013) studied the well-being of people held in Australian detention centres and found people placed in detention for unauthorised boat arrival or unauthorised air arrival to have significantly higher rates of self-harm (17,7% and 14,4%) compared with only 3,6% for people overstaying their visas and 2,1% for illegal foreign fishers. The government however maintains the view that mandatory detention of undocumented arrivals is necessary to deter asylum seekers from travelling by boat to Australia in the future.

Political Power

As previously mentioned, political power is influenced through the ‘enactment of policy and law’ (Ramos 2017, p. 5). The Australian policy of mandatory detention for asylum seekers was first introduced in 1992 by the Keating Government (Anderson 2015). In 2001, Prime Minister John Howard famously declared: “we will decide who comes to this country, and the circumstances in which they come” (Nethery 2010, p. 181). This tough stance towards immigration has been adopted by successive governments since then (Nethery 2010). Under Section 198AD of the Migration Act1958 asylum seekers who arrive by boat to Australia without a valid visa must be taken to a regional processing centre (Karlsen 2016). Asylum seekers who arrived without an authorised visa by boat between 13 August 2012 and 1 January 2014 may be put through a ‘fast track’ visa assessment process, if granted approval by the Immigration Minister (Australian Human Rights Commission, p.1). Since 19 July 2013, people seeking asylum who arrive by boat to Australia are sent to detention centres in PNG and Nauru for offshore processing (Refugee Council of Australia 2017a). Adopting the policy of offshore processing has several consequences, most obviously ‘public scrutiny and external review’ is significantly reduced and providing ‘effective health and mental health services’ becomes extremely difficult (Newman, Proctor & Dudley 2013, p.316).

Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) (UDHR) provides a right to seek asylum from a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a social group or political opinion. Additionally, Article 3(1) of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees(1951) states that Australia has an obligation not to impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry and presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory without authorisation, provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.

Despite this, Australia still maintains an approach of penalising unauthorised asylum seekers who arrive by boat by placing them in an offshore processing centre indefinitely. In October 2016, it was reported that application for refugee status by 941 out of the 1,195 people on Nauru were accepted (Karlsen 2016). Respective figures for those on Manus island were 675 out of the 822 (Karlsen 2016).

The harsh conditions asylum seekers face in offshore processing centres are said to be a direct ‘tactic of government to encourage asylum seekers to give up their refugee claims and return to their home country’ (Fleay and Hoffman 2014, p. 4).

Additionally, Newman, Proctor and Dudley (2013, p.315) put forth the view that, the policy approach towards the offshore processing of asylum seekers has been upheld with bipartisan support due to the belief that it acts as a ‘significant deterrent to unauthorised arrivals’. Despite this, a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) study in 2011 found no significant correlation between “the threat of being placed in detention” and “discouragement from seeking asylum” (Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013). In further support of this position, a joint research project undertaken by the International Detention Coalition and the La Trobe Refugee Research Centre (2011, cited in Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013, p.21) found that asylum seekers having understanding of detention policy, consider this regulation as ‘an unavoidable part of the journey’.

Governmentality refers to ‘the strategies and tactics used by government to shape and influence the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours of resident populations’ (Fleay & Hoffman 2014, p.4). Nethery (2010, p.181) puts forth the view that current and previous Australian governments have constructed a ‘populist ideology about migration matters’. Under such a view, these governments have maintained the idea that matters of immigration and border security ‘should be determined by the Australian people – via their elected government – and not by the courts or by human rights organisations’ (Nethery 2010, p.181).

Button and Evans (2016, p.2) argue that the Australian Government has taken several measures to prevent the Australian public being provided with ‘sufficient information to assess whether these policies are necessary or appropriate’. The Government has ensured that it controls the public’s access to information ‘that might cause a negative response’ (Fleay & Hoffman 2014, p.6). Most obvious of these measures is the decision to criminalise ‘the disclosure of human rights violations by whistle-blowers’ (Button & Evans 2016, p.2). Other measures taken to make offshore processing of asylum seekers in PNG and Nauru less transparent include: Australian laws which ‘criminalise whistleblowing disclosures by those working within the offshore processing system’; the ‘restrictive approach to the presence of foreign journalists in Nauru’; and the banning of Facebook by the Nauru Government (Button & Evans 2016, p.15).

Cultural Power

As previously mentioned, cultural power ‘expresses influence through mediating levels of legitimacy and shaping the public idea of good’ (Ramos 2017, p.5). Although successive Australian Governments have ‘maintained bipartisan support for multiculturalism since the 1970s’, the Refugee Council of Australia (2017) believes that such policies are being undermined by ‘the inhuman treatment of people seeking asylum’ to Australia. The terms asylum seekers, refugees, illegals, queue jumpers and boat people are often used ‘interchangeably and/or incorrectly’ (Phillips 2015). Jones (2017) highlights that the historic White Policy of 1901 in Australia saw the banning of people of non-European descent migrating to Australia. It has previously been argued that the philosophy of the White Australia policy still has an influence on Australian migration policies in the 21st Century (Jones 2017). Jones (2017 p.2) has argued that, as a policy “White Australia is gone. But as an ideology, it arguably lingers on”. Despite popular representations within the media that asylum seekers and refugees take Australian jobs, the Refugee Council of Australia (2017) makes it clear that asylum seekers in community detention do not have the right to work in Australia. The Refugee Council of Australia (2017b) reports that many asylum seekers face ‘significant hardship’ as they live in inadequate housing and skip meals as they are forced to survive on an ‘inadequate level of income’

Australia may be the most culturally diverse country in the developed world. Around one in two Australians have at least one parent born overseas. In fact, Australia has a higher proportion of people born overseas (26 percent) than Canada (22 percent), New Zealand (23 percent) and the United Kingdom (13 percent) — and nearly twice the proportion as in the United States (14 percent).

Despite its historic ties to Britain, overseas-born Australians are for the first time more Asian than European, and all together, Australians speak more than 300 languages and subscribe to over 100 religions (Baidawi, 2017). Migrants make an enormous contribution to Australia’s economy and provide an estimated fiscal benefit of over $ 10 billion in their first ten years of settlement (Australian Human Rights Commission). In 2010-11, international education activity contributed $16,3 billion to the Australian economy (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011). As statistics have shown us, there is even no kind of pure Australian nation. Australians are mostly people who want to find a new way to live or people who seek for the change in their life. Shortly, they are migrants who are seeking for something new in their life.

Furthermore, there is no big difference between old migrants and recent migrants but for the time. Due to that fact, Australians and the government would be expected to approach to the new migrants with more common sense as does the population, more than half of which considers that Australia should welcome refugees (The Lowy Institute Poll 2017).

On the empty side of the glass, there is still almost half population who do not welcome refugees or defend an Anglo-spheric Australian population. In the 2016 federal elections, One Nation party got 4,3 percent of the votes for the Senate. The party is known for its advocacy for white supremacy in Australia. Also hidden racists, and racism cannot be seen in the surveys or statistics due to social desirability bias. It is a fact that in daily life there are a lot of bulling cases in Australia.

As stated in the Human Rights Watch Report of 2016, despite its solid record of protecting civil and political rights, Australian senior government officials have not only dismissed criticism on its treatment of refugees and asylum seekers but they have also discredited institutions reporting such maltreatment and instituted vague counterterrorism laws that does not in any way address the core of the problem. Despite lack of clarity on the real motives behind such behaviour, several reasons can be cited contributing to the negative look.

At the top of the list comes interlocking financial and cultural reasons. Generally, economic uncertainty effects common culture in Australia. Declining of the Australian labour market led to an increasing social inequality in the community. Social inequality created fear of losing jobs to the outsiders ( McSwiney, J. and D. Cottle 2017). Especially monetarisation of the social order with neoliberalist policies around the world (Campfens 1997) has caused economy to influence social and cultural relationships more than it was. Lowy Institute’s poll (2017) reflects more cultural perception. The poll shows that Australians` concern about the negative direction of the world has reached very high levels. 79% of Australians` are dissatisfied with the incidents taking place in the world. The poll further verifies the concerns about Australia also. 48% of the Australians` are dissatisfied about the direction that Australia is taking.

48% of Australians say asylum seekers currently in offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Islands ‘should never be settled in Australia’, while 45% say they ‘should be settled in Australia’. As the statistics have shown us, there is an increase of fear amongst Australians and this effect their stance towards migrants, asylum seekers and vulnerable people. As an outcome of this fear, populist radical right One Nation Party(ONP) has been able to garner some popular support. As economy declines, fear and tendency towards avoiding uncertainty amongst people increase. Consequently, general understanding of the world and culture push Australians to become more apprehensive and conservative.

48% of Australians say asylum seekers currently in offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Islands ‘should never be settled in Australia’, while 45% say they ‘should be settled in Australia’. As the statistics have shown us, there is an increase of fear amongst Australians and this effect their stance towards migrants, asylum seekers and vulnerable people. As an outcome of this fear, populist radical right One Nation Party(ONP) has been able to garner some popular support. As economy declines, fear and tendency towards avoiding uncertainty amongst people increase. Consequently, general understanding of the world and culture push Australians to become more apprehensive and conservative.

The last twenty years considered, two main events have played considerable role in building fear and anger against Muslims in Western societies to include Anglosphere. First one is the 9/11 attacks in USA and the second one is the rise of global jihadist movement. In the wake of the event, the President of the United Sates George Bush had said “You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terror” (CNN 6 November 2001). After that speech, anger and externalization towards Muslims in USA and other developed countries such as England ensued.

Second event is the nascence of ISIS. The Salafi jihadist organisation since its inception with Islamic State in Iraq in 2006 has committed every kind of terrorist act running the gamut from live online beheadings to mass killings with cries of “Allahuakbar” (God is great) in the name of Islam, which is from head toe against any act of terror or barbarism (Sultan 2014)” However using that Islamic term creates fear and also hatred against Muslims. This hatred and fear can be used by politicians like Trump and Pauline Hanson. For example, Pauline Hanson’s proposal on the Muslim ban after London terror attack, saying: `Islam is a disease’ is an exact proof of that effect even despite Malcolm Turnbull’s statement against her proposal. (The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 March 2017). Additionally, ISIS making that process much more easier for those who want to split the world into two pieces. Because, the dynamics of ISIS – violence and chaos – is creating cultural structures and stereotypes of non-western people and these are used by politicians to demonise. The process is further creating negative discourse and creating gaps between cultures. Moreover, that new gap creates fear against outsiders among Australian Society.

Asylum seekers who are being processed while living within the community are provided funding under the Asylum Seekers Assistance Scheme and Community Assistance Support Program (Phillips 2015). In 2015, the ‘financial component of such assistance amounted to $458.88 per fortnight for a single person’ (Phillips 2015). A common myth highlighted by the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (2013, p.28) is that ‘refugees will strain our economy and threaten “our way of life”. For ASRC these views are ‘vastly exaggerated’. In fact, the Refugee Council of Australia (2010, cited in Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013, p. 28) sees the circumstances quite contrary. The Council reported that refugees arriving from Vietnam in the 1970-80’s ‘brought with them myriad business and cultural knowledge and skills which have developed into vital trade links with much of South-East Asia’.

The Refugee Council of Australia (2017b) has reported that discrimination is major issue affecting migrant communities in the workplace. Racism can affect asylum seekers and refugees both emotionally and psychologically and may also result in further forms of discrimination and segregation. In 2016, a Scanlon Foundation survey mapping social cohesion found that racism is a serious problem in Australia (Refugee Council of Australia 2017b). By tolerating offensive, humiliating and intimidating language the door is opened for more severe acts of harassment, intimidation or violence. The Scanlon Foundation survey ‘Mapping Social Cohesion’ found that 27% of refugees who came from Non-English backgrounds had experienced discrimination in the past year, 31% had experienced discrimination once a month or in ‘most weeks of the year’, 53% of those who experienced discrimination were verbally abused, 17% were not offered work or were not treated fairly in their job, 8% had been physically attacked, and 22-25% of people , reported a negative opinion towards Muslims (Refugee Council of Australia 2017b). The Refugee Council of Australia (2017b) also reports often discrimination in the classroom, where many have been verbally abused and treated unfairly by their educators and peers. It is clear that racism and discrimination impacts this segment of the community in terms of health, education and employment (Refugee Council of Australia 2017b).

Still, Australia accepts a designated number of immigrants each year in accordance with the humanitarian program. The program has two key mechanisms. Those are first to provide protection to asylum seekers arriving in Australia with a valid visa. The second is protection for those who have had their application granted in another country prior to arriving Australia. The Australian Government between 2014 and 2015, accepted 13.750 people under its humanitarian program.

Economic Power

As previously mentioned, economic power is influenced with the exertion of wealth (Ramos 2017). The economic aspect of offshore detention centres in Nauru and Manus Island becomes a very important consideration in policy making. The issue needs to be revisited from the perspectives of the Australian government, Australian people or civil society, the state of Nauru and Papua New Guinea, and the companies who run the centres. The economic aspect includes financing the establishment of the centres, the maintenance of the facilities, meals for the detainees, education and health programs as well as other administrative costs to run the facilities. According to Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) (2017) ‘Under the agreements, the Australian Government was to bear all costs associated with the construction and operation of the centres. Transfers of asylum seekers to Nauru commenced on 14 September 2012 and to PNG on Manus Island on 21 November 2012’ to facilitate this process for Australian government’. In December 2016, the combined value of the contracts for operating the regional processing centres in Nauru and PNG was reportedly $ 3386 million (Australian National Audit Office 2017).

From the civil society perspective, the detention centres cost the government and public tax money. Hirsch (2015) reported that in 2014-2015 fiscal year, the Australian Government spent $ 2,91 billion for operating the facilities. The amount was spent to fund 634 people in Nauru and 943 people in Manus Island. The amount per person corresponds to an average of $ 400.000 annually. The immensity of the amount is better understood when compared to the budget of United Nations High Commissioner which had to look after 46,3 million refugees, internally displaced people and stateless people worldwide for a budget of $3,72 billion in 2014. With about the same amount Australia just detained and deterred few thousand asylum seekers. For instance, Kilalea (2016) said that the Manus island is the island of $1 billion, where the Australian tax-payers money has been spent on places called ‘hellish prison camp’. There are also other describing the island as ‘Australia’s Guantanamo in the Hearts of the Pacific Ocean.’ This amount of money could have been better spent on the services and facilities within Australian territory.

The Greens political party senator Sarah Hanson-Young (cited in Kilalea 2016) has previously declared that ‘the centres were not only “cruel and illegal” but also immensely expensive to operate.

‘This money would be better spent on schools, hospitals, and on support for the homeless, but instead the government has spent billions on being cruel to people seeking asylum’ (Sarah Hanson-Young, cited in Kilalea 2016). On the other hand, Martin (2017) is concerned about whether that money could be better spent on onshore asylum seeker centre in Australia instead of operating them in PNG and Nauru. Martin (2017) describes the research done by Tony Ward, an economist at Melbourne University. The study found that to process one case in offshore detention costs around $1.200,00 per day, however, it costs half of that to process in an onshore centre, which is what it requires to put someone up in a luxury hotel. The research also found that, visa processing in the community is a cheaper option compared with offshore detention centres (Martin 2017).

An Australian civil society organisation highlights the economic benefit of resettling asylum seekers in Australia. It is argued that refugees and asylum seekers substantially contribute to national economic growth. For example, they expand markets for local goods, open the market to new opportunities and they also bring in new skills to the country (Hirsch 2015). Another study suggests that those who have arrived in Australia as refugees are more likely to be entrepreneurs, open new businesses and on top of that their children are more likely to graduate from high-level education and potentially being a professional in their career. As an example, research done by AMES, and Deloitte Access Economics on the lives of Karen refugees from Burma found that their resettlement in the small town of Victoria has contributed to an estimated $41.49 million to the local economy from 2010-2014. The Karen people contributed to the economy of the region notably from new businesses and the employment forces. They also contributed to the population decline issue in the area, attracting more government funding and increasing social capital among the local community (AMESH 2015).

The economic perspective of the company in dealing with the detention centre is pure to make a profit. Currently, both Nauru and Manus Island detention centres are managed by Transfield which is now called Broadspectrum with $2 billion contracts for two years. With this arrangement, the company led to increase their profit from $8,4 million in 2015 to $25 million in 2016; they are also administered to the reduction of their debt significantly (Pash 2016). On the other hand, apart from funding the centre through Broadspectrum, the government also spent over $100 million on regional deterrence programs. The program aims to intercept asylum seeker movement from their country of origin or their transit country. To succeed this program, the Australian Government work closely with Indonesia, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka to control the boat smugglers and their activities (Parliament of Australia 2015).

During negotiations for the reopening of the Manus Island detention centre, ‘Australia promised the PNG Government $400 million in aid to construct a new hospital in Lae’ (Button & Evans 2016, p.59). The Australian Government also committed to helping the Nauru Government with funding almost 15% of their total budget. This year an estimated $24,5 million was channelled to Nauru through Official Development Assistance (ODA) and bilateral cooperation program. The funding aims to support the enhancement of public sector development, investing in the infrastructure of the country and human capital development (DFAT 2017). The development aid package to PNG aims to help fund their public-sector development; promote economic growth, health and education; and strengthen human development within the country. The budget has significantly increased from $420 million in 2015 to $546,3 million in 2017 for ODA (DFAT 2017).

During its four years of operation, both detention centres have cost Australia over $2 billion. However, the money appears to be inappropriately spent for the operation of programs. The ANAO found during their audit of the expenditure that the payments of $2,3 billion made from September 2012 – April 2016 were not recorded accurately, and that there was some abuse of power where the non-authorised officer provided payment authorisation to the company. In addition, there were also some irregularities found in the payment system and the contract with the companies operating the offshore processing centres (ANAO 2016). With this situation, the Australian public should have questioned the Government over the use of taxpayer money to operate the offshore detention centres.

Alternative/Solution

As highlighted above, Australia has clearly failed to fulfil its obligations under international law with respect to the human rights of asylum seekers.

Australia’s sovereignty does not provide the right to ‘override international law and violate the human rights of certain persons’ (Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law 2015, p.3). As was also mentioned, there appears to be ‘no correlation between the threat of being placed in detention and discouragement in seeking asylum’ (UNHCR 2011, cited in Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that Australia’s harsh stance towards unauthorised arrivals will do little to prevent people from continuing to make the trip by sea. In response to this, one possible alternative to the Australian Government policy of offshore processing of asylum seekers who arrive by sea is that of community processing (Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013). Alternative measures such as these are reported to be much more cost effective (UNHCR 2006, cited in Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013) and should therefore apply to all modes of arrival, including those asylum seekers who arrive by sea. What makes Australia well suited to receive a large intake of refugees is the fact that Australia is a nation of immigrants, with European settlement roughly 200 years ago. Since then, there have been waves of immigration especially following World War II. Australia is a successful multicultural nation in many ways.

Cosmopolitanism describes ‘the view that all human beings have equal moral standing within a single world community’ (Hayden 2004, cited in Ramos 2010, p.43). For Hayden (2004, p. 70 cited in Ramos 2010, p.44) cosmopolitanism suggests that ‘global political order ought to be constructed grounded on the equal legal rights… of all individuals’ (Hayden, 2004, p.70). Held (2000 cited in Ramos 2010, p.45) argues that, ‘global forces escape the reach of territorially based polities, they erode the capacity of nation states to pursue programmes of regulation, accountability and social justice in many spheres’. Despite the right to seek asylum under Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights(1948) (UDHR) and Article 3(1) of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees(1951) stating that Australia has an obligation to ‘not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry and presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory without authorisation’, Australia has continued to treat unauthorised asylum seekers as different to authorised asylum seekers. We believe that employing the Transnational Advocacy Network strategy to address the issue may not be so effective in Australia, especially if taking into consideration the fact that many previous Australian Governments have disagreed with findings published by the United Nations about failing to fulfil its obligations under international human rights law.

For change to be induced, it is necessary that non-government and civil society organisations are in active dialogue with policymakers ‘about the needs and interests of the people they serve’ (Ayner 2010, p.347). Advocacy refers to ‘general support for an idea of issue’ while lobbying refers to ‘asking for a particular action on a discrete proposal’ (Ayner 2010, p.348). In order to find a suitable strategy to change the position of the government we recommend the use of media and documentaries to increase public awareness about the harsh conditions asylum seekers are faced with due to the policy of offshore processing. Charles (2013, p.384) advocates the view that ‘the so-called mainstream media’ is frequently ‘criticised for serving only the interests of the political and economic elite’. Therefore, to draw attention to the situation faced by many asylum seekers in PNG and Nauru, it is important to find alternative mechanisms to effectively achieve this.

Social media can be used as an effective tool to help raise awareness about the issue of offshore processing of asylum seekers and the harsh conditions many are faced with. Sources of social media can be used to publish a film documentary in order to reach a wide audience, highlighting the injustice, the harsh conditions and the stories of asylum seekers on PNG and Nauru. There are several other tools such as internet, social media, radio and newspaper that can be useful to expand information at both the local and international level so the information spreads to a wider audience. For instance, Dr Fiona McKay, lecturer at the School of Health and Social Development, Deakin University has undertaken research using film documentary as a research tool to highlight the experiences of asylum seekers and refugee communities. She has stated that although ‘people use social media to cultivate a positive self-image, they can equally be interested in engaging in issues of social justice’ (Mckay 2016, p.1).

Mckay (2016) points out that social media has been a vital resource for helping to communicate political, social and economic ideas to the government and the general community.It plays a significant role due to the ability for people to express their personal thoughts regarding a specific topic. Mckay (2016, p.1) looks into the issues of ‘meaningful’ support of asylum seeker activism and refugee advocacy in online engagement’. Social media is flexible and permits that people have the possibility of deciding how and how much to be involved with the topic. Mckay (2016) has also reported that online campaigning can lead to policy change. In the 21st century, digital video can be transferred, shared and uploaded through YouTube, Vimeo, Facebook and other forms of communication that support and help users to publish their messages and stories (Mara 2012, p.3).

However, Lo Bianco et al., (2010, cited in Mara 2012) makes it clear that not everybody has experienced the same quality of participation with social media and the internet. Therefore, culture and language, educational level, age, language fluency, socio-economic status, communication preferences, knowledge related to technology and other aspects effect the level of participation online (Mara 2012). The use of the internet can be limited, especially for those who have arrived as immigrants because they tend to have limited economic means. Despite this, social media can be an exclusive online medium where people can participate in the progress, health and wellbeing of the community by sharing and using tools such as digital film and documentary (Mara 2012). Burgess & Green (2009, cited in the Department of Health 2010) make the assertion that social media may bring new chances for using digital video promoting a healthy environment in Australia in peace with refugee and migrant communities from diverse cultural backgrounds.

We recommend employing an advocacy journalism approach, creating a social media campaign using short storytelling interviews with asylum seekers in offshore processing centres to draw the Australian public’s attention to the issue. Using the advocacy journalism method for change can be very effective as the journalist becomes ‘a campaigner immersed in a story to call for and foster real social change’ (Charles 2013, p.384). Advocacy journalism can be an effective in ‘giving the other a face and a voice’ (Careless 2000, cited in Charles 2013, p. 386). Another associated benefit of advocacy journalism is that it can extract the audience out of their comfort zone ‘to provoke some form of action for change (Charles 2013, p.387).

References:

AMESH 2015, Small Town Big Returns; Economic and Social Impact of the Karen Resettlement in Nhill, viewed 28 October 2017, <https://www.ames.net.au/files/file/Research/19933%20AMES%20Nhill%20Report%20LR.pdf>.

Anderson, S 2015, ‘Explore the history of Australia’s asylum seeker policy’, SBS, 24 July, viewed 11 October 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/news/explainer/explore-history-australias-asylum-seeker-policy>.

Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 2013, Asylum seekers and refugees: myths facts and solutions, Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, Melbourne, viewed 11 October 2017, <https://www.asrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/MythBusterJuly2013FINAL.pdf>.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, ‘Australian Social Trends’ viewed 30 October 2017,http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features20Dec+2011

Australian Human Rights Commission 2017, ‘Face the Facts: Cultural Diversity’ viewed 30 October 2017, https://www.humanrights.gov.au/face-facts-cultural-diversity

Australian Human Rights Commission 2007, Asylum seekers and refugees guide, Australian Human Rights Commission, viewed 24 October 2017, <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/asylum-seekers-and-refugees-guide>.

Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) 2017, Offshore Processing Centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea: Management of Garrison Support and Welfare Services, Performance Audit Report no 32 of 2016-2017, viewed 21 October 2017, <https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/offshore-processing-centres-nauru-and-papua-new-guinea-contract-management>.

Ayner, M 2010, Advocacy, Lobbying and Social Change’, In O. Renzo, D (ed.) 2010, ‘The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management’, 3rd ed., Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Baidawi, A 2017, ‘Australia, Diverse and Graying. Also: Johnny Depp, and a Controversial Push to Decrypt’, The New York Times, 26 June, viewed 21 October 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/26/world/australia/australia-census-more-diverse-older-same-sex-couples.html.

Button, L & Evans, S 2016, At What Cost? The Human, Economic and Strategic Cost of Australia’s Asylum Seeker Policies and the Alternatives, UNICEF Australia & Save the Children Australia, viewed 12 October 2017, <https://www.unicef.org.au/Upload/UNICEF/Media/Documents/At-What-Cost-Report.pdf>.

Campfens , H 1997 , Community Development Around the World: Practice, Theory, Research, Training , University of Toronto Press , Toronto

Charles, M 2013, News Documentary and Advocacy Journalism In K. Fowler, K. Watt, K. & S. Allan (eds.), Journalism: New Challenges, Poole, England: CJCR: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research. Bournemouth University.

DFAT 2017, Development Assistance in Nauru, viewed 30 October 2017, <http://dfat.gov.au/geo/nauru/development-assistance/Pages/development-assistance-in-nauru.aspx>.

DFAT 2017, Development Assistance in Papua New Guinea, viewed 30 October 2017, <http://dfat.gov.au/geo/papua-new-guinea/development-assistance/Pages/papua-new-guinea.aspx>.

Fleay, C & Hoffman, S 2014, ‘Despair as a governing strategy: Australia and the offshore processing of asylum-seekers on Nauru’, Refugee Survey Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 1-19.

Hirsch, A 2015, The Economic Cost of Australian Asylum Policy, viewed 25 October 2017, http://rightnow.org.au/opinion-3/the-economic-cost-of-australias-asylum-policies

Human Rights Watch Report 2016, ‘Australia: Events of 2016’ , viewed 30 October 2017, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/australia#5a664c

Human Rights Watch 2016, Country Summary: Australia January 2016, Human Rights Watch, viewed 12 October 2017, <http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/australia.pdf>.

Jones, B 2017, ‘What was the White Australian Policy and how does it still affect us now?’, NITV, viewed 23 October 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2017/04/10/what-was-white-australia-policy-and-how-does-it-still-affect-us-now>.

Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law 2015, Offshore processing: Australia’s responsibility for asylum seekers and refugees in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, viewed 12 October 2017, <http://www.kaldorcentre.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/Factsheet_Offshore_processing_state_responsibility.pdf>.

Karlsen, E 2016, Australia’s offshore processing of asylum seekers in Nauru and PNG: a quick guide to statistics and resources, Department of Parliamentary Services: Commonwealth of Australia, viewed 11 October 2017, <http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlinfo/download/library/prspub/4129609/upload_binary/4129606.pdf;fileType=application/pdf>.

Kilalea, D 2016, Manus Island Detention Centre to close: Money could have been better spent on services, viewed 21 October 2017, <http://www.news.com.au/finance/economy/australian-economy/manus-island-detention-centre-to-close-money-could-have-been-better-spent-on-services/news-story/d1642b669ff57c1cddd3abca8b12df88>.

Mara, B, 2012, Social Media, Digital Video and Health Promotion in a Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Australia, viewed 24 October 2017, <https://academic.oup.com/heapro/article/28/3/466/634183/Social-media-digital-video-and-health-promotion-in>.

Martin, P 2017, The Appalling Mathematics of Offshore Detention, viewed 26 October 2017, <http://www.smh.com.au/comment/the-appalling-mathematics-of-offshore-detention-20170830-gy6ztl.html>.

McKay, F 2016, Social media, public tokenism and asylum seeker activism: can Facebook provide ‘meaningful’ support? Bang the Table, viewed 24 October 2017, <http://www.bangthetable.com/social-media-asylum-seeker-activism/>.

McSwiney, J & Cottle, D 2017, ‘Unintended consequences: One nation and neoliberalism in contemporary Australia’ Journal of Australian Political Economy, vol 2017, no. 79, pp. 87-106.

Nethery, A 2010, Immigration Detention in Australia, PhD thesis, Deakin University, Melbourne, viewed 13 October 2017, <https://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30032385/nethery-immigrationdetention-2010A.pdf>.

Newman, L., Proctor, N & Dudley, M 2013, ‘Seeking asylum in Australia: Immigration detention, human rights and mental health care’, Australasian Psychiatry, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 315-320.

Parliament of Australia 2015, Budget Review 2014-2015; Counter-people smuggling measures, viewed 29 October 2017,<https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201415/PeopleSmuggling>.

Pash, C 2016, Detention centre operator Broadspectrum triples its profit, viewed 23 October 2017, <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/detention-centre-operator-broadspectrum-triples-its-profit-2016-2>.

Phillips, J 2015, Asylum seekers and refugees: What are the facts?, Department of Parliamentary Services: Commonwealth of Australia, viewed 13 October 2017, <http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1415/AsylumFacts>.

Ramos, J 2010, Alternative Futures of Globalisation: A Socio-Ecological Study of the World Social Forum Process, PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology.

Ramos, J 2017, ‘Re-imagining Structural Synergies of Power: A Method for the Strategic Development of the Commons’, Centre for Cultural Diversity and Wellbeing: Victoria University.

Refugee Council of Australia 2017a, Recent changes in Australian refugee policy, Refugee Council of Australia, viewed 20 October 2017, <https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/publications/recent-changes-australian-refugee-policy/>.

Refugee Council of Australia 2017b, Submission on strengthening multiculturalism, Refugee Council of Australia, viewed 23 October 2017, <https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/publications/submissions/strengthening-multiculturalism/>.

Smith, A 2017, ‘Exclusive: leaked report reveals ‘extreme’ levels of racism in Queensland public health system’, SBS, viewed 23 October 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2017/10/23/exclusive-leaked-report-reveals-extreme-levels-racism-queensland-public-health?cx_navSource=related-side-cx#cxrecs_s>.

Sultan, O 2014, ‘ISIS Crisis and Implications for US and Turkey’, Unpublished manuscript, Strategical Studies Institute: Istanbul, Turkey.