Abstract

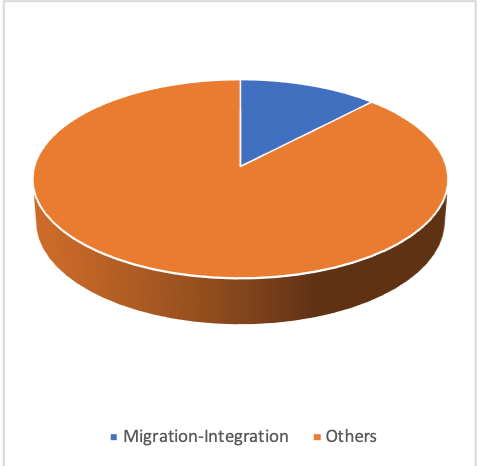

This study analyses the projects related to the integration of migrants and refugees in Flanders. The author conducts a systematic review of related projects appearing in the ESF and AMIF[*] Project database between 2013 and 2019. The results of the research revealed that integration related projects comprised 8.1% of ESF and AMIF Projects in numbers (235 of 2,900). The research indicates that projects aiming at integration of migrants/refugees have increased by 40% in number after 2015, a sharp increase when compared to earlier periods, a fact attributable to the outbreak of migration crisis in Europe. Relevant projects under study define migrants, refugees, other language speakers, third-country nationals (non-EU) as the target group and social inclusion, integration, labour market integration, human capital, mentoring, coaching as topics and tools. The current body of integration projects focus mainly on language education and employing migrants in bottleneck sectors. This study clearly shows that a conventional mapping and evaluation of these projects needs to be undertaken for an effective allocation of funds on most needed subjects and fields addressing human and social capital.

Introduction

Having peaked in 2015 (1.3 million), number of refugees in Europe has first stabilised in 2016 and has fallen just below 600.000 by 2018, a more manageable size for the EU. From the distribution perspective, by the end of 2018, 64% of asylum applicants resided in five North-West European Countries, namely Belgium, Germany, France, United Kingdom and Sweden. (United Nations, 2017). Total number of asylum applications in Belgium in the last ten years constitutes 2,25% of the host population, which is twice of the EU28 average. It was difficult to anticipate the flow in 2015 and coordinate efforts to respond as required within and across different levels and offices of governments. (OECD, International Migration Outlook 2018, 2018) The integration of the coming migrants has emerged as an essential part of this response , and many countries have primarily tried to cope with this problem depending on their existing tools and mechanisms.

The purpose of the study is to make a systematic review of projects funded through ESF and AMIF to integrate migrants and refugees in Flanders between 2014 and 2019, in order to illustrate existing efforts and identify underexplored areas or approaches. This article is an attempt to provide an answer to “What are the underexplored areas in integration of migrants via ESF and AMIF Projects?”. This research has been built upon data in the project map and database of ESF Flanders. After identifying the universe of such funded projects, the author conduct analysis of the integration-related projects, including a content analysis of 235 projects.

Conceptual Framework

In this study projects of two different organisations’ projects are analysed, namely the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and the European Social Fund (ESF). AMIF is established by Directive 2014/516/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on 16 April 2014. Directive underlines some thirty tasks, seven of which are related to the integration. These tasks are;

- to promote effective integration of refugees and displaced persons identified as eligible for resettlement by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (‘UNHCR’),

- preparation of the integration process already in the country of origin of the third-country nationals coming to the Union,

- to pursue a more targeted approach, in support of consistent strategies specifically designed to promote the integration of third-country nationals at national, local and/or regional level, where appropriate,

- to ensure a comprehensive approach to integration, taking into account the specificities of those target groups including applicants for international protection),

- to ensure the consistency of the Union’s response to the integration of third-country nationals,

- to enhance the capacity of Member States to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate in general all immigration and integration strategies,

- to take account of … anti-discrimination principles.[†]

On the other hand, the European Social Fund (ESF) was established by Directive 2013/1304/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on 17 December 2013. ESF was also put forward to support integration. Some responsibilities of ESF are social inclusion and sustainable integration into the labour market of young people including young people at risk of social exclusion, to improve integration into employment, education and training, thereby enhancing social inclusion, reducing inequalities, in particular for those who face multiple discrimination, to strengthen social inclusion.[‡]

Definition of “integration” is “the action or process of successfully joining or mixing with a different group of people” or ”the action or process of combining two or more things in an effective way” and “the process of becoming part of a group of people” in business English. Many scholars (R. D. Alba, Logan, Stults, Marzan, & Zhang, 1999; Harker, 2001; Safi, 2010; Stodolska, 1998; Waters & Jimenez, 2005) use the term of integration as a step-in assimilation and acculturation process. Within the context of this study, the term will refer to either “joining to the society as a regular member” or to “employment in a sector in accordance with the previous education and experience at the same or similar level”. On the other hand, so many scholars (Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, & Perhoniemi, 2007; Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; Roder & Muhlau, 2011; Stevens, Hussein, & Manthorpe, 2012) stressed discrimination between migrants and host nation citizens in their studies. We can conclude as a result of these definitions and studies that “discrimination” is deemed to be an obstacle before integration or has been used as the opposite of the latter.

According to (Xhardez, 2016), the challenge of immigration and in particular the integration of new migrants to the host society is particularly tangible in Belgium. Implementation of different integration policies within different federate entities has caused a dualism or more precisely two distinct integration programmes in the same country. This institutional situation has consequences for the stakeholders, especially the migrants themselves. Integration works in Flanders (which is applicable in Brussels [not compulsory for residents]) consist of social integration, language learning, career guidance (professional, educational and social perspectives) and programme counselling. Extant research mainly focuses on social and educational policies, although integration policies were about identities according to (Adam, 2013) who has focused on immigrant integration policy issues.

Christof Roos categorises migration according to motivations such as economic migration, labour/educational migration, family-related migration or humanitarian immigration. This research doesn’t cover the third motivation type immigrants who possibly have more diverse educational levels. (Roos, 2013) (IOM, 2009)

According to Wiesbrock education levels of native citizens and immigrants does not have a significant impact on the disparities in employment rates for low level educated people (up to secondary education). The gap for the immigrants with tertiary education and same level citizens becomes wider, although education has a positive impact on the employability of migrants. This gap gets wider as immigrants with higher education usually face difficulties in the recognition of their qualifications obtained abroad. (OECD, International Migration Outlook, 2008) Furthermore, some employers tend to consider formal foreign qualifications to be inferior to national ones. (OECD, International Migration Outlook 2016, 2016).

While the labour market performance of refugees mainly depends on their previous education and skills, language and technical training improve their integration into the labour market. Good formal education for supplementary skill acquisition is not sufficient to remove obstacles in the labour market integration such as discrimination and low esteem on existing qualifications. (Peschner, 2017)

Methodology

The author scrutinised the ESF and AMIF projects, which are mostly related to integration, social inclusion of migrants and refugees into the labour market, between May and June of 2019. “Migrant”, “refugee”, “other language speakers”, “integration”, “discrimination”, “third-country nationals”, “human capital”, “mentoring” and “coaching” were the key words in advanced search. The period was limited to January 2014 through May 2019. The search turned 253 results that constituted the universe of the research. Finally, the results were classified, analysed, and visualised for the research question.

Results

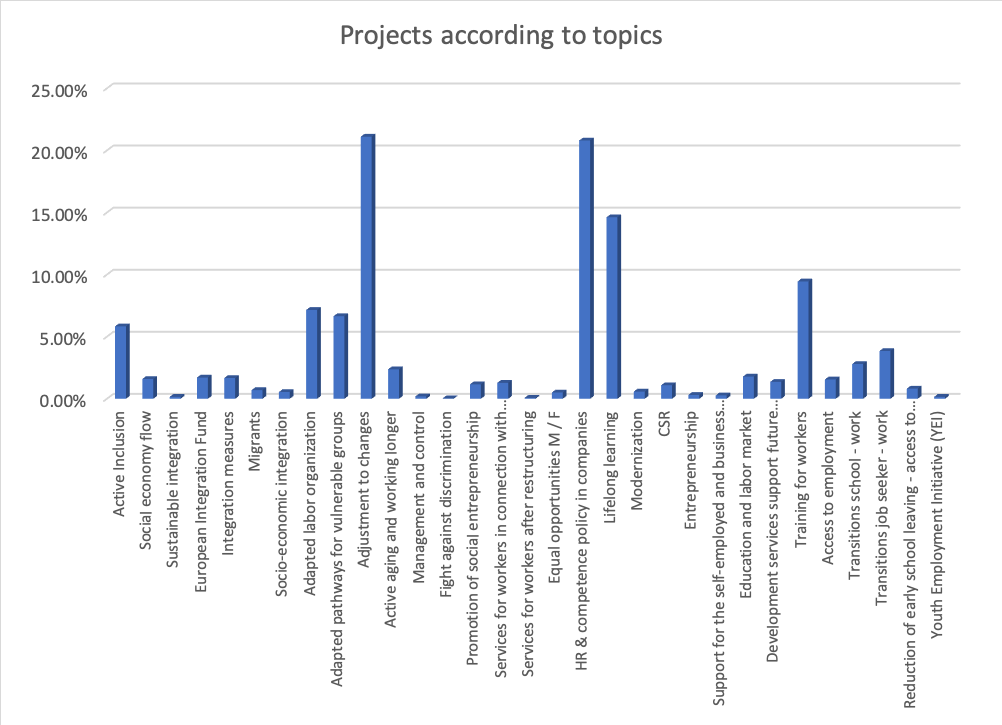

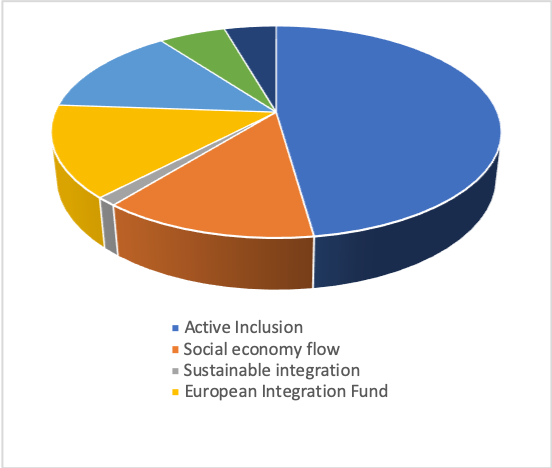

There are a total of 2,900 projects funded through AMIF and ESF in Flanders between 2014 and 2019. Through integration related project calls (Active Inclusion, Social economy flow, Sustainable integration, European Integration Fund, Integration measures, Integration measures and Socio-economic integration) 314 projects have been funded which constitute 10,83% of total project calls in numbers (See Table 1-2). Among these integration related projects, “active inclusion” theme has the most prominent portion by %48, while “sustainable integration” takes the last place by 1,27%. When these figures are compared with the number of responsibilities of AMIF (7 of 30 was related to the integration) it can be argued that these numbers don’t correlate with the responsibilities. Additionally, when we detract projects which are not focused on the refugees and migrants this number decreases to 235.

Table 1: Project distribution by topic

Table 2: Integration Projects vs others

Table 3: Integration Projects Distribution by topic

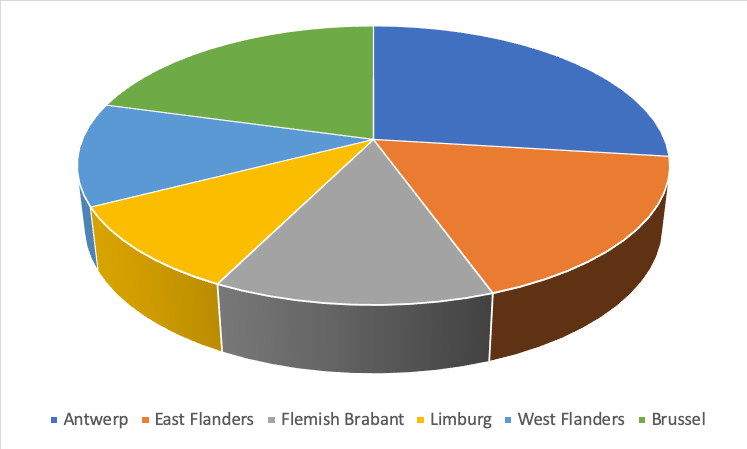

According to the regional comparison of integration related projects, Antwerp takes the first place by 27% while Brussels is the second by %21. It is understandable that Antwerp has the first place since it is the biggest city in Flanders with its significant business sector and great diversity. Brussels, on the other hand, has been home to projects with more general focus rather than regional. Other municipalities’ project shares have been proportionate to their population with no statistical significance. (see table 4)

Table 4: Integration Projects by regions

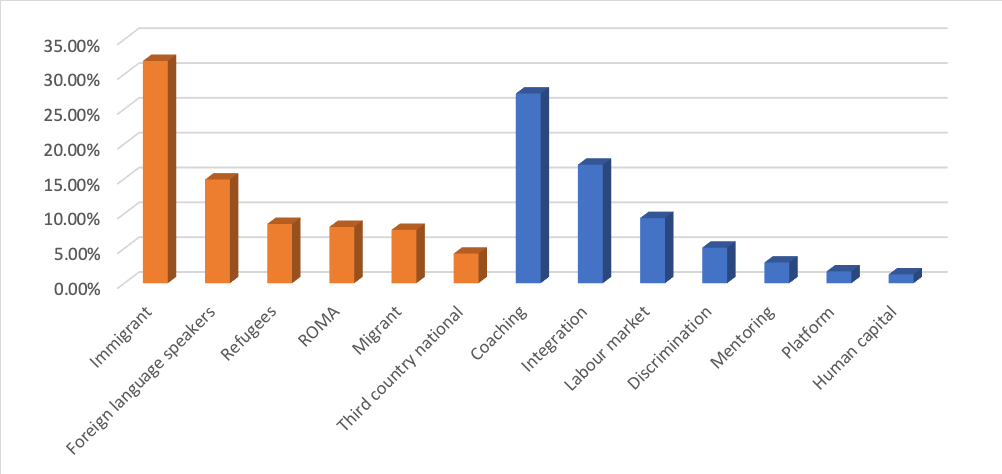

When we compare integration related projects according to their focus groups and methodologies through a word search, we see that main focus is immigrants with 31.91% while foreign language speakers and refugees take the second and third priorities with 14.89% and 8.51% consecutively. “Article 60”, “coaching” and “integration” were the most focused terms in the methodology search. Coaching projects mainly focus on internship or temporary employment whereby a fixed sample group in a specific labour field train/inform apprentices from bottom to up or adapt previous training and experiences to regional needs.

Table 5: Integration Projects by keywords

As can be seen on Table 5, 75 projects (27,23% of integration related projects) intend to adapt target groups with a subsidy from the government to the labour market. These projects mainly focus on a fixed amount of people for specific jobs and does not seek to establish continuous stand-alone systems.

There are some projects which are focused on having a specific target to hire or educate a fixed number of refugees/migrants to a particular sector. In such projects, the undertaker seeks to make batches of migrants (about 25 on average) receiving social help from OCMW to benefit from Art.60. Such projects are far from being sustainable. Rather than integrating the migrant / refugee, they seek to shift the local social benefit pool to the federal one. In the long run, those projects provide a temporary solution for a limited number of people. What is more, the system is sector or target oriented instead of being system and customer oriented.

Although discrimination is one of the most significant barriers in front of migrants and refugees to be employed, only 12 projects use the “discrimination” term in their projects. 8 of these projects aim to prevent or decrease the level of discrimination in different societies whereas only remaining four aim to prevent discrimination in the integration process.

Discussion

Most of the projects focus on the fixed sample group of migrants and refugees while none of the projects, but two, focus on the highly educated refugees and migrants. As can be understood from the definition of integration, which is joining, mixing, combining two different groups of people, needs and expectations of both host society and the coming group should be taken into account. Nearly all of the projects have tried to integrate migrants and immigrants according to the gaps, needs, expectations of the host society or labour market. In order to reach a successful integration, more ways should be explored to accommodate those of the migrants / refugees.

Another important aspect of the projects is the closed eco-system they form. It is not possible to reach the results of these projects for researchers. A stipulation of providing the project results may lead to more sophisticated evaluation which could better equip policy makers / officials with more insight on achievements, accomplishments and failures of these projects and make better choices in following project calls.

AMIF and ESF databases give access to the information of promoters rather than the whole consortium to include project partners. Lack of this information prevents researchers from evaluating the comprehensiveness of these projects. Reaching only to the information of the promoter does not give a full picture which further precludes understanding if migrant and refugees have taken a driving role in those projects or if the latter has been just subjects. It might be argued that unilaterally established and implemented projects cannot produce intended results and success entails ensuring active engagement of this target group.

As one of the main obstacles to the labour market integration, discrimination has not been sufficiently focused. Additionally, labour market integration is based on three pillar pillars: labour market, migrants/refugees and government institutions. This research shows that many projects focused on integration of immigrants into the labour market, whereas some others focus on the business world. Only few projects combine these two. It is unfortunate that none of the projects follow a holistic approach by focusing on government institutions and engaging officials. The projects which aim at the third pillar of integration (government institutions) and especially social assistants of those organisations will arguably contribute to the integration.

Many local projects such as employing/training/internship in an organisation by using article 60 might be useful locally or within pilot projects. It would be better to generalise and institutionalise these kinds of projects instead of repeating with the same principles when they succeed.

Conclusion

After the refugee surge in 2015, Flemish authorities tried hard to tackle with the urgent problem at hand and its aftershocks. Integration of these refugees and migrants was a task that was considered to come after pressing issues such as housing. ESF and AMIF proved to have been excellent tools for the administrators to handle this strategic issue of integration which required a foresight and long term planning while they were deeply involved on daily needs of the migrants such as accommodation and food. Both organisations have funded many projects in all regions of Flanders. However, as can be easily seen from this analysis, successful bottom-up projects (regional, sectoral, timely narrow-scaled) were replicated in the same regions and on the same basis instead of institutionalisation and their expansion to other regions / municipalities.

Second, little evidence, if any, found on regional or sectoral cooperation among projects or know-how, experience sharing which, at thez end, would be time saving as well as source friendly.

Third, some key concepts such as discrimination have not been sufficiently addressed which is one of the main barriers between the migrants/refugees and the labour market. There is need for a thorough gap analysis in integration projects with the collaboration of scholars and NGO’s for further project calls.

To sum up, as immigrants continue to clutter in Flanders, the integration problem will continue to grow like a snowball. There is a need for an in-depth analysis of projects which have been in effect up to now, and a comprehensive approach for further project calls.

This analysis is done via project summaries from the ESF and AMIF databases. Further analysis needs to be undertaken based on access to project results which would provide better view of these projects

* Erdem Taskin is project manager and research fellow at Beyond the Horizon ISSG.

Bibliography

Adam, I. (2013). Immigrant Integration Policies of the Belgian Regions: Substate Nationalism and Policy Divergence after Devolution. Regional & Federal Studies, 23(5), 547-569.

Huddleston, T., & Vink, M. P. (2015). Full membership or equal rights? The link between naturalisation and integration policies for immigrants in 29 European states. Cooperative Migration Studies, 1-19.

IOM. (2009). Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

OECD. (2008). International Migration Outlook. OECD.

OECD. (2016). International Migration Outlook 2016. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). International Migration Outlook 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Peschner, J. (2017, 1). Labour market performance of refugees in the EU. Brussels: European Commission.

Peter, D., & Garibay, M. (2013). An evaluation framework for the Flemish integration policies. Leuven: Steunpunt Inburgering en Integratie.

Roos, C. (2013). The EU and Immigration Policies – Cracks in the Walls of Fortress Europe? Palgrave Macmillan.

Xhardez, C. (2016). The integration of new immigrants in Brussels: an institutional and political puzzle. Brussels Studies [Online], 1-19.

[*] ESF refers to European Social Funds whereas AMIF stands for Asylum Migration Integration Fund.

[†] Regulation 2014/516/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on establishing the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund, (L 150, 20.05.2014, p. 168-195).

[‡] Regulation 2013/1304/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on the European Social Fund, (L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 470-486).

Contact

Phone

Tel: +32 (0) 2 801 13 57-58

Address

Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Davincilaan 1, 1932 Brussels