A Critique of Hybrid Warfare Concept

It was retired Marine Officer Frank Hoffman who popularised the Hybrid warfare concept in a series of articles and books since it was first publicly used in 2005 in a conference, by General Mattis, the U.S. General Secretary of Defense who resigned in last October. For Hoffman, hybrid warfare can shortly be defined as the combination of different modes of war in the same battlefield, which is a military-dominant approach. However, Russia’s invasion of Crimea was a milestone, not only for the West-Russia relations, but also for the content and the use of hybrid warfare concept. The term gained huge popularity after Russia’s invasion of Crimea. NATO and EU, labelling Russia’s activities as hybrid warfare, adopted the term in their strategic documents. If we look at the definitions of NATO and EU, we can see that these later definitions include more broader aspects such as economy, disinformation, diplomacy in addition to the Hoffman’s more military-oriented definition. In fact, Hoffman himself confessed in an article in 2014 that his theory fails to capture non-violent actions, such as economic, subversive acts or information operations.

While the concept is used widely by NATO, EU or Western nations and politicians, analysts, there is also an increasing number of critiques about the validity and the use of the concept. The critiques can be grouped in four main titles. First of all, the term is criticised to be ambiguous, it so inclusive and broad that it loses its value to be analytically useful. It actually describes warfare itself and every conflict can be named as hybrid as long as it doesn’t have the characteristics of single form of warfare. Secondly, almost everybody agree that it is not new. As American scholar Echevarria noted, from a historical standpoint, hybrid war has been the norm in fact, but it is the conventional war that has been the illusion. And Thirdly, like many new concepts, it encourages tactical thinking focused upon enemy’s way of fighting, rather than upon strategy, or the strategic effectiveness. And finally, by creating another war category, in addition to traditional and irregular warfare, it urges us to expect future conflicts to be in hybrid character and this causes us to miss the real complexity of warfare, as the war can take infinite forms in the tactical level.

For instance, in another research I carried out with a colleague, we made a “content analysis” of 66 media items such as the news articles and commentaries in which the term “hybrid warfare” is used. We concluded that only in 18 items the term was used in its true meaning. The authors implied “information warfare” in 20 items, “political warfare” in 14 items, “unconventional warfare” in 5 items, “conventional warfare” in 2 items, “irregular warfare” in 1 item, “comprehensive approach” in 1 item and “subversive warfare” in 1 item when they used the term “hybrid warfare”. In 4 items, no specific meaning could be determined. This ongoing study demonstrates that hybrid warfare is an ambiguous concept which international community cannot agree upon.

But hybrid warfare is not alone in its effort to conceptualise the contemporary warfare. Compound Warfare, New Wars, Asymmetric Conflict, Fourth-Generation Warfare, Revolution in Military Affairs, Network Centric Warfare, Effects Based Operations, Comprehensive Approach, Political Warfare are some examples to the concepts and terms that have emerged since the end of Cold War. But as the time passed by, most of them become passé and lost their popularity, but probably just to return in future, with a slightly different name, when similar conditions arise. It is understandable, even commendable, that analysts make effort to conceptualise contemporary warfare. However, the opportunity cost of misconception is too high, as it creates confusion rather than clarity and obscures the strategic thought. These attempts to categorize war usually discount the role of strategy whereas Strategy lies at the nexus of all dimensions of warfare and it is only through strategy where the character of warfare takes shape.

All the terms/concepts have right aspects in their observations and assessments about contemporary warfare. However, there is a common fallacy of generalising from specifics of their own period and labeling these generalisations with a new term as if they are a new type of war. First, Hoffman generalised from the specifics of the war between Israel-Hezbollah in 2006, then the U.S. generalised from the specifics of Afghanistan and Iraq Wars and recently defense community has generalised from the specifics of Russian activities in Crimea and Ukraine. It seems that warfare is redefined in relation to the characteristics of each conflict Gray calls it as “presentism”, which means the tendency to see the current problems as unique and fail to see historical continuities. Lonsdale draws attention to “reductionism”, which means concentrating on just one or two of the many dimensions of strategy and suggesting that success can be gained through this particular dimension. In fact, war is an elephant, though it may appear in hybrid, compound, irregular, traditional or other forms—depending upon one’s view of it. And in most cases, analysts describe one part of this elephant. What we need is a more holistic approach to warfare, and to understand what the constants and variables of warfare are. I believe, strategic theory might be the answer to what we are looking for.

Strategic Theory and Hybrid Warfare

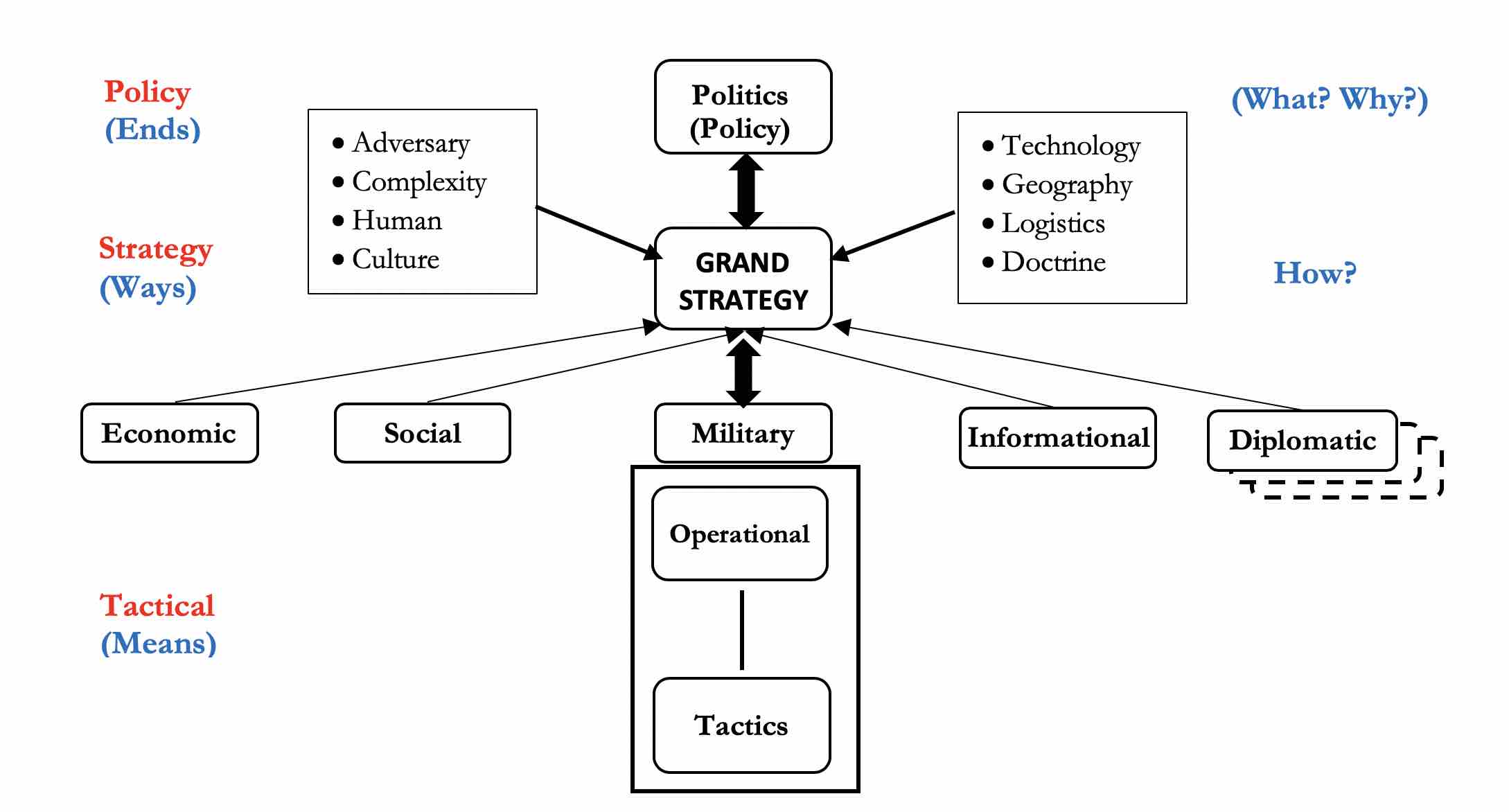

So, what is strategy and strategic theory? Strategic theory is a general term that refers to the interconnected principles pertained to strategy and grand strategy. It assumes that all wars share certain common characteristics and it provides a guidance on how to manage the complexities of using force to achieve policy ends. While strategy has a narrower meaning restricted to the use of military as a tool, it always must be nested in a broader framework, which is called grand strategy. In contemporary literature, grand strategy usually refers to “national strategy” or “national security strategy” for the states. To complicate the things further, strategy as a term, though technically restricted to the use of military, is usually used with strategic theory interchangeably. Therefore, when I said strategy, I mean strategic theory. Below, I tried to depict those principles and common characteristics in a nutshell, while it is very difficult indeed to include all details. It is a depiction of the universal and eternal features of strategy-making, which means this construct works in every conflict whether we are cognisant of it or not.

Strategy is usually divided into three essential components: ends + ways + means where “policy end”, denotes the goals we aspire to achieve, “strategic ways” correspond to the alternative courses of action to follow, and “means” are the resources that we can use. In an ideal world, politics produces policy; strategy connects policy with means by determining required capabilities/forces and by assigning specific tasks to those forces that can achieve policy goals; and finally, operational and tactical levels execute those concrete tasks decided by the strategy.

The levels are different in nature and they answer different questions. Policy answers to the question of “why and what”, while strategy seeks an answer for “how”; and operational/tactical levels do it. At the operational/tactical levels, operations can take infinite forms, from humanitarian aid to full conventional war.

A good strategy is expected to be one in which all three components are tuned, that is, the means are sufficient to accomplish the ends through the designated ways. The most challenging part in this structure is to convert military power and other tools into political effect. It is extremely difficult because it requires an exceptional talent to determine which actions or which combination of different dimensions match policy ends. This is called strategy, and it ensures all levels function properly. It is more an art than science. Despite huge advances in technology, there is no scientific method to determine how much military power- or other national powers- is enough or when balance is achieved. This largely depends on strategic sense and judgement of strategists. Another reason to why the strategy is so difficult is the fact that warfare or conflicts are very complex. War is “a function of interconnected variables” whose weights differs by the context and circumstances. One scholar uses a “bridge” metaphor, name it as “strategy bridge” to explain the instrumentality function of the strategy. This bridge must operate in both ways; therefore, the strategist does not just translate policy intentions to operations but also to adjust policy in the light of operations. This is done through constant negotiation between levels and among the dimensions, by a civilian-military partnership. It is usually a committee process.

There might be cases that military plays no part. Instead of direct use of force, sometimes, only the threat of force can provide the desired effects. But whether it is the leading component or not, military is indispensable in designing and executing strategy and grand strategy. For this reason, putting strategy in practice requires an appreciation for military power, what it can and cannot do, and how they can be linked to form operations and campaigns to achieve policy goals. Apart from non-military dimensions, which are economic, social, informational and diplomatic dimensions, as you can see in the slide, arguably, there are eight eternal factors of the strategy, namely adversary, complexity, human, culture, technology, geography, logistics and doctrine, which needs to be taken into account and are valid for all conflicts, whereas their relative weights depend on the context of each specific case.

I would like to draw your attention that whether we aware of strategic theory and we plan our activities through these principles or not, this mechanism works. Every conflict has different dimensions. Fewer dimensions might be in action in a limited operation while all dimensions and factors are in full use in a major conflict.

So, if we go back to hybrid warfare and want to see where it falls under the realm of strategy, I claim that hybrid warfare was mainly about operational and tactical levels until 2014. Only after Russia’s annexation of Crimea that defense community began to incorporate other dimensions. However, this time the focus was rather on informational dimension, which means that hybrid warfare is usually seen as a variant of propaganda, psychological and information operations. I believe that war is war that you can conduct in many different ways. What is required is to have a holistic vision of the strategic context and the adaptability to meet unique challenges of the day through the use of all instruments of grand strategy. As mentioned, at the operational and tactical level, operations can take infinite forms. given that every challenge is unique in many important details, they must first be assessed at the level of grand strategy. If it is decided that the challenge requires a military reaction, then grand strategy must employ military instrument tailored against that specific challenge.

Recommendations and Implications for Europe

So far, the right perspective that is believed to adopted for approaching to the warfare and conflicts is summarised. In this section, some advises and implications for Europe are provided considering the current security and defence posture of EU. I would like to start by pointing to the need for a change in the defence mentality especially of policy makers and key decision makers.

There is a shocking Youtube video where General Wesley Clark, then Chief of Staff, Head of Armed Forces of the U.S., explains how the U.S. made the decision to make a war against Iraq and seven other countries in Middle East. Firstly, it is very surprising that General Clark was not involved in decision-making process. Secondly, this is a very good example to the complete loss of strategy, of which we are still experiencing dire consequences in Afghanistan and Middle East, even in Africa. And history is full of these examples. Was the war against Afghanistan and Iraq the best option for the U.S. to eliminate terrorism? I don’t think so. General Clark’s says “if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem has to look like a nail.” Of course, the U.S. had many tools other than military, the problem was decision-makers at that time were not aware of that. As I mentioned, it requires exceptional talent to determine which tactical actions match policy ends. Unfortunately, in democracies, politicians and decision-makers, in general, do not have required appreciation of strategy-making.

Of course, the change is needed not only in the mentality, but also in the structure. It doesn’t necessarily requires adding a new layer or a new institution. It is more about how different existing components work better together. Recently EU has taken some important steps, like PESCO and EDF, whose main aim is to jointly develop defense capabilities, and it is very important, but I think is still about increasing tactical capacities. Again, strategic and policy levels are neglected.

I believe, EU needs a committee supported by intelligence and high-quality staff, whose function is to convert EU’s defence policies to actions, or vice versa, to ensure that tactical deeds are tuned with these policies. To be able to do that, this committee should have a cross-departmental ability to work in collaboration with EU institutions in other dimensions. The key issue here is to have ability to handle cross-cutting issues, because the silo thinking or some say, stove piping is the current biggest challenge of EU structure. In fact, External Action Service is a good candidate to assume this responsibility, as many of its current tasks overlap with the committee proposed here. But it should be transformed to a service that can carry out this bridge function between policy and means, and that have an ability to better collaborate with other dimensions.

When it comes to NATO-EU relations; as many analysts suggested, I support to idea that NATO and EU could be complementary to each other as NATO is mainly a military organisation focused on collective defence and EU has capabilities in other dimensions. However, if EU can transform itself and has this working mechanism from policy to tactical level, which balance the essential components of strategy; NATO would become a major part of EU’s military tool, rather than an alliance that EU based all its defence on. As NATO-EU complementary relationship goes on, EU could keep on improving its defence posture through crisis management operations, such as in Mali and Bosnia. Because these operations are currently conducted on ad hoc mechanisms rather than well-designed structure.

With the same logic, if succeeded in designing and institutionalising its defence posture, EU can and should create its own regular army as well, beginning with military headquarters like NATO’s SHAPE. I believe, a European Army wouldn’t conflict with NATO. Because NATO, especially the U.S. would prefer a stronger EU in that sense to ease the burden on its shoulders. There might be some concerns regarding the cost of such an army, but I do not think it will cause a considerable cost as member states have already national forces perform in accordance with NATO standards. Apart from all, EU definitely needs its own army if it wants to be global actor, in other words if it wants to get its strategic autonomy.

Last but not least, all recommendations explained here depends one important fact, which is “EU members’ willingness to see EU as a Global Actor” in their sincere thoughts. I personally believe there is no other way for EU members than to build a sound defence and security structure. But there is much to do, to persuade policy makers and populations of EU member states.