Hybrid warfare has become new orthodoxy in international community which allegedly describe the characteristics of contemporary warfare. Furthermore, ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict is almost unanimously referred as a model for hybrid warfare. However, both hybrid warfare as a term itself or the referring Russia’s war as a model for hybrid warfare might lead analysts, defence planners and policymakers down an unhelpful path. There is a risk of rediscovering old ideas while defining the parameters of current warfare, which might fall short of expectations.

After the collapse of Soviet Union, there have been a dramatic increase in the number of new terms and concepts as a result of efforts to understand contemporary warfare. Before 9/11, especially during 90s, the defense community debated intensely over whether the nature of war itself had changed. Many believed that a “Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA),” “Military Transformation,” and a “New American Way of War” was going to lift the fog of war and the armies that caught the informational revolution would have a tremendous supremacy over their enemies. After 9/11, The West and especially U.S. conducted an unconventional type of war in the Middle East, Afghanistan and some other locations, which was generally called as Global War Against Terrorism (GWOT). With the aim of distinguishing contemporary practices from traditional or conventional wars, analysts and scholars have raced to assign labels such as “hybrid” wars, “gray zone” conflicts, “unrestricted warfare,” or “new generation” wars, “asymmetric conflict”, “fourth-generation warfare”, “shock and awe”, “full spectrum dominance”, among others. Some analysts called them as buzzwords because they quickly become outdated.

However much of the concepts presented by new terms limited themselves to tactical level arrangements, weapon systems and hypothetical threats. (Linn, 2007) Stoker points the lack of definitional clarity as one of the main reasons of failure on analyzing military affairs and strategic issues. Buzzwords and jargon clouds these fields and weaken the ability to understand and explain past—and more importantly—current conflicts. Gray Zone Wars, which is being discussed intensely nowadays, were already studied by many authors in 1950s, in the same context, with regard to the conflicts on the periphery of Russia under the name of “war in the gray zone.” According to Stoker, unnecessary increase in the number of terms creates confusion and linguistic opacity instead of producing clarity, whereas it is clarity that we need. (Stoker, 2016) Echevarria criticizes security experts for perceiving the recent events in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq and South China Sea as a new form of warfare and for calling them hybrid or gray zone wars. For him, these wars are classic coercive strategies. (Echevarria, 2016)

On the one hand, there are scholars claiming that the oversupply of the concepts causes confusion and impairs the development of sound counter-strategies, it causes the core meaning of strategy slip away. Other camp claims that contemporary warfare has unprecedented features and characteristics that requires new paradigms and terms. Taking the latest term- hybrid warfare as the case, this paper aims to present a critique of the hybrid warfare concept and to demonstrate the fallacy of labelling ongoing Russia-Ukraine Conflict as a model of hybrid warfare. Definition of hybrid warfare concept seems to consist of so many characteristics of contemporary warfare in a way that one may not deny its prudence. In other words, it seems to be repackaging of any number of other concepts like compound warfare, three blocks war or fourth generation warfare. However, its weakness as a concept may serve as a drawback to make true strategy. (Cox, Bruscino, & Ryan, 2012)

The first part includes the definition, background and the main characteristics of hybrid warfare as a concept. It is aimed to provide a description of the term without any assessment so that readers could understand as it prevailed in academic community. The second part summarizes the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Again, it is presented without subjective view, based on the facts on the ground. The third part questions the hybrid term on conceptual basis and explain why the term is weak as a concept. The fourth part examines the labelling Russia-Ukraine Conflict as Hybrid Warfare through the critical approach. In this part, it is queried whether it is true to name the conflict between Russia and Ukraine as hybrid warfare. Finally, the fifth part interprets why it is problematic to categorize warfare and draws the reader’s attention to the importance of a general theory of war and strategy with universal applicability.

- The Concept of Hybrid Warfare

General James N. Mattis, USMC, was the first to use hybrid term publicly on September 8, 2005, in Arlington, Virginia, at the fourth annual Sea Services Forum. In the same year, General Mattis and Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman, USMCR (Ret.) formulated the hybrid concept as a reaction to the US 2005 National Defense Strategy (NDS) statement of that “An array of traditional, irregular, catastrophic, and disruptive capabilities and methods threaten U.S. interests….” They argued that future conflicts will not be in the pure forms of warfare, rather they be a merger of different modes. They called this new type [emphasis added] of warfare as hybrid warfare. (Poli, 2010)

Frank Hoffman further developed the concept in a series of articles and books. In an article in 2007, he opined that “Hybrid threats incorporate a full range of different modes of warfare including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder. Hybrid Wars can be conducted by both states and a variety of non-state actors. These multi-modal activities can be conducted by separate units, or even by the same unit, but are generally operationally and tactically directed and coordinated within the main battlespace to achieve synergistic effects in the physical and psychological dimension of conflict.” According to Hoffman the main characteristics of hybrid wars are “multi-dimensionality,” “operational integration,” and “exploitation of the information domain”. (Hoffman, 2007) The last version of Hofmann’s definition of hybrid threat is “[a]ny adversary that simultaneously and adaptively employs a fused mix of conventional weapons, irregular tactics, terrorism and criminal behaviour in the battle space to obtain their political objectives.” (Hoffman, 2009)

Although he admits that hybrid warfare is not new and many wars in the past have had regular and irregular components, he claimed those wars had been performed in different theaters or in distinct formations whereas regular and irregular forces have become blurred into the same force in the same battlespace today. If one is to summarize the study of Hoffman at one word, it would be “blurring”. Hoffman thinks that different types of war and different kinds of forces with various technologies merged in the contemporary battlefield, which made the war more complex than in the past.

While claiming that future wars will be a merge of forces, actors and tactics, Hoffman admits that it does not represent a replacement for conventional war. Rather, hybrid war is a complicating factor for defense planning in the 21st Century and an aid to understand the latest changes in the character of warfare. (Hoffman 2007) Hoffman suggests that the new type of warfare he introduces is consistent with Clausewitz’s strategic theory. Referring to Clausewitz, he opines that every age has its own conception of war. In this sense, hybrid warfare explains the warfare of this age.

Popularized by Hoffman, hybrid warfare has become as common as to appear like new orthodoxy in military thought (Poli, 2010). Defense Community widely accepts that current wars and conflicts are in hybrid form. Contemporary doctrines, documents, papers etc. are full of references to hybrid concept. Hybrid threat term has already been adopted by US Army, Navy, Marine Corps doctrines and national planning documents. (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015).

NATO (2015) agreed at Wales Summit in 2014 and confirmed at Warsaw Summit in 2016 to formulate a strategy against the hybrid threats, as its one of the main objectives. It seems that NATO have adopted a very similar hybrid concept to what Hoffman suggested. At NATO Transformation Seminar, which was held in Washington DC between 24-26 March 2015, it was agreed that Hybrid warfare and its supporting tactics can include broad, complex, adaptive, opportunistic and often integrated combinations of conventional and unconventional methods. These activities can be overt or covert, involving military, paramilitary, organized criminal networks and civilian actors across all elements of power (“NATO Transformation Seminar,” 2015). NATO’s efforts on Hybrid Warfare remarkably increased after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 as NATO defines Russia’s warfare concept as Hybrid Warfare.

Looking over the studies on hybrid warfare, one can suggest the following items as main characteristics of hybrid threat;

- Usually implies a blurring of the distinction between military and civilian, thus refers primarily to a mix of diverse instruments across a broad spectrum (use of military force, technology, criminality, terrorism, economic pressure, humanitarian and religious means, intelligence, sabotage, disinformation) (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015),

- Involves non-state actors such as militias, transnational criminal groups or terrorist networks (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015),

- Seizes every opportunity to use both traditional and modern media instruments so as to develop new narratives based on their interests, means and aims(Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015), which could be defined as information warfare either via psychological operations or offensive cyber-attacks (Eve & Piret, 2015) or propaganda (Heidi & Aleksandr, 2015).

Proponents of the concept argue that it well defines contemporary wars. According to them, wars/conflicts in near or mid-term will be hybrid in character. They claim that what Hezbollah did against Israel in 2006 and what Russia did against Ukraine in 2014 were good examples of hybrid warfare concept. Especially ongoing Russia-Ukraine Conflict is almost unanimously referred as a model for hybrid warfare and Russia’s neighbors and the West cannot stand up against this new approach. Before examining hybrid warfare concept through the lens of critical thinking, it is better to understand Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Following part will present outlines of the conflict.

2. Russia-Ukraine Conflict

A West-East divide in Ukraine can be seen in both the main language spoken and who people vote for. The division of the country can be traced back to 1930s when Stalin conducted a deadly famine and replaced the eastern Ukrainians with millions of deported Russians. (Chalupa, 2013). The nationalistic West is Ukrainian-speaking and welcomes the E.U., while the Russian-speaking East, where former President Victor Yanukovcyh rose to power, sees the Kremlin as an indispensable ally and wants to remain outside the E.U.

The “Orange Revolution” in November 2004 promised economic and political change in Ukraine but the government’s attempts to integrate with Europe didn’t prove successful because of the divided public opinion. In 2010, President Viktor Yanukovych won the presidential elections, and in November 2013 abandoned an agreement on closer trade ties with EU. Instead, he sought closer cooperation with Russia, which resulted in huge demonstrations in Kyev. Although Putin agreed to buy $15bn of Ukrainian debt and reduce the price of Russian gas supplies by about a third, protests didn’t stop. On 22nd February 2014, President Yanukovych disappeared and protesters took control of presidential administration buildings. In late February 2014, Parliament voted to ban Russian as the second official language, causing a wave of anger in Russian-speaking regions; although the vote is later overturned (“Ukraine crisis: Timeline,” 2014).

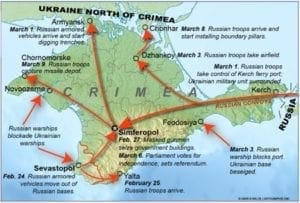

Since late February 2014, Russia has conducted two distinct lines of operations in Ukraine. One is occupation and annexation of Crimea, the other is the invasion of Eastern Ukraine’s Donbas Industrial Region. Russia had historic naval base of Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, Crimea. Russian armoured vehicles moved out of Russian bases on 24 February. Masked Pro-Russian gunmen seized key buildings in the Crimean capital, Simferopol. Unidentified gunmen appeared outside Crimea’s main airports. Between 25 February-09 March (see Figure 1),

- The Russian troops took control of Kerch ferry port in the far east of Crimea, Ukrainian military unit surrendered (March 1),

- Russian armoured vehicles arrived to Armyansk in the far north of Crimea and started digging trenches (March 1),

- A Russian warship blocked port Feodosiya in the east (March 3),

- Russian troops took Dzhankoy airfield at north (March 3),

- The Parliament voted for independence and set for referendum (March 6),

- Russian troops arrived Chonhar at north and started installing boundary pillars (March 8),

- Russian troops captured Chornomorske missile depot at Northwest (March 9),

- Meanwhile, Russian warships blockade western coasts at Novoozerne and Sevastopol.

Figure 1- Russian Invasion of Crimea in 2014.

Figure 1- Russian Invasion of Crimea in 2014.

https://blogs.nvcc.edu/damiller/2014/03/10/russias-crimea-conquest/ (22 May 2016)

Beginning as a covert military operation, combining ambiguity and disinformation, the annexation of Crimea was completed by a traditional military invasion. (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015) Referendum on joining Russia was held on March 16 and was backed by %97 of voters. The Western countries rejected the results because it was believed as a sham. According to the leaked documents real support was around %50-60 (“Ukraine crisis: Timeline,” 2014).

After the annexation of Crimea, US and EU declared to impose sanctions, including travel bans, on some of Russia’s key figures. However, one shouldn’t forget that Russia supplies about a quarter of Europe’s gas, and just over half of that flowing through Ukraine. Ability to cut gas supplies is an important advantage for Russia against Western states threatens to impose economic sanctions. (Korchemkin, 2014)

Just after Ukrainian troops withdrew from Crimea, large Russian troops started gathering on the border of Eastern Ukrainian. On April 7, pro-Russian protesters occupied government buildings in the eastern cities of Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv. A number of pro-Russian leaders declared that a referendum on granting greater autonomy to eastern regions will be held. Separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk declared independence after the West announced not to recognize the referendums. Meanwhile, large Russian military build-up on the border caused concerns that another annexation could take place.

On 25 May, Petro Poroshenko was elected as new president with more than 55% of the vote, in which much of the eastern part didn’t involve. He announced a peace-plan and a week-long truce but it held only a few days after a Ukrainian helicopter was shot down. Ukraine accused Russian regular forces for involving the fight and allowing well-trained volunteers and heavy weapons to cross the border to help the rebels. Although Russia denied, Russia’s help and the direct intervention became reality (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015).

A ceasefire was agreed on September 5 in Minsk between Ukraine and pro-Russian rebels. However, it took only four days when fighting erupted around Donetsk Airport. After repeated violations of truce, by 19 September, rebels succeeded to control a stretch along the Russian border.

Pro-West parties won the parliament elections held on October 26. But the East, controlled by rebels didn’t recognize the elections and didn’t vote. They hold their own elections on 2 November and declared the winners. In January 2015, fighting between Ukrainian army and rebels intensified and army had to withdraw from Donetsk airport, which is strategically very important, on 22 January (“Ukraine Crisis in Maps,” 2015).

The rebels continued their offensive in February. A second Minsk ceasefire was agreed on 12 February. This time agreement was between Russia, Ukraine, Germany and France. The deal included weapon withdrawals and prisoner exchanges, but main issues weren’t settled. Skirmishes and shelling continued in some parts of the conflict zones. At the end of February, both sides withdrew their artillery from the front lines as it was specified in the agreement. Since Second Minsk agreement, number of violations occurred along with negotiations between Ukraine and separatists. But it seems no compromise could have been reached. It became a deadlock (Whitmore, 2015).

The Russian strategy during the Eastern Ukrainian operations seems to concentrate its armed forces in the border as a show of force, then support the separatists by sending armaments and trainers (Heidi & Aleksandr, 2015).

During the operations, targeted and systematic disinformation campaigns are carried out by Russia at every form like trying to discredit the Kyiv government as fascist and using every possible channel to undermine Ukraine’s democracy. Russian authorities labelled Ukrainian movement as fascist to awaken memories of the Soviet fight against Nazi Germany. Putin even compared Ukrainian military actions to Nazis blockading Leningrad in Second World War. Russia denied the unidentified troops in Crimea being Russian soldiers, denied its involvement in operations in Eastern Ukraine even in the face of growing evidence. When the Ukrainian army seemed to move against rebels, the Kremlin changed its position presenting itself as the defender of humanitarian issues. The propaganda machinery has been used to manage the perceptions of both internal and international community during the operations (Heidi & Aleksandr, 2015).

3. Critical Assessment of Hybrid Warfare Concept

Despite its prominence as the latest buzzword, the above-mentioned “unique” characteristics of hybrid warfare go back as far as the Peloponnesian War in the fifth century (Murray & Mansoor, 2012). In almost every warfare, diverse instruments have been used; often time it was the creativity of leaders at using different instruments that provided victory. Hybrid opponents have always formed a difficult and powerful combination. Even in World War II -which is widely accepted as one of the most conventional warfares- the role of Soviet partisans and other irregulars along with Soviet conventional forces, was formidable on the Eastern Front (Murray & Mansoor, 2012). Needless to say, propaganda has been very much effective tool throughout the history of warfare. Although modern communication systems provide amplifying affect to the dissemination of information, propaganda is a time-honoured tradition.

Many studies on Hybrid Warfare state that it is not new. However, rationales presented just afterwards on what makes the hybrid warfare unique or worth to study are not satisfactory. Here are some examples of rationales why hybrid warfare is unique;

- It explains the unseen scale of use and exploitation of old tools in new ways (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015),

- It is useful in providing perspectives on the rising complexity of NATO’s security challenge (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015),

- It is one of the few concepts that allows for differentiated views on the security challenges emanating from NATO’s South and East at the same time (Jacobs & Lasconjarias, 2015),

- It suggests many of the technologies used in warfare, especially in Russia-Ukraine Conflict, inspire new challenges (Eve & Piret, 2015),

- It is a useful means of thinking about war’s past, present and future (Murray & Mansoor, 2012),

- It is a useful construct to analyse conflicts involving regular and irregular forces engaged in both symmetric and asymmetric combat (Murray & Mansoor, 2012),

- It is the combination and orchestration of different actions that achieves a surprise effect and creates ambiguity, making an adequate reaction extremely difficult (Heidi & Aleksandr, 2015).

None of these explanations is satisfactory enough to interpret why we need a hybrid warfare concept to understand new developments in security environment. Wars or warfare always includes the possibility of exploiting old tools in new ways. A new category of warfare is not needed to understand war’s past, today’s complex security environment, or new challenges of future. An objective knowledge of history, accurate intelligence is still relevant to understand contemporary wars. Rationales presented to explain what is new in hybrid warfare are simply not adequate.

Another flaw in the Hybrid warfare concept is that it attributes too much power to the enemy. A hybrid threat becomes an enemy almost with mystical powers (Cox et al., 2012). As it is indicated in the definition, a hybrid threat, which is a state or non-state, could employ conventional, irregular, terrorist and criminal activities simultaneously, even by the same unit. This argument could be admitted for a state actor like Russia to some extent, but for non-state actors like ISIL and Hezbollah, it is hard to imagine. If they could have this ability, they would not apply suicide missions.

Almost every Russian action is interpreted as part of a well-coordinated “hybrid warfare” campaign. This approach gives the Russian leadership an unrealistic degree of strategic prowess. Renz (2016) successfully points to the similarities between today and 1960s by quoting the following text from John F. Kennedy’s speech.

We are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence – on intimidation instead of free choice, on guerrillas by night instead of armies by day. It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations.

(Kennedy, 1961)

Bear in mind that what Kennedy implies in his speech was the Soviets. It is interesting to see the similarities of enemy’s capabilities referred such as “covert means”, “intimidation”, “combining military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations”. Today’s strategic prowess, Russia is also frequently referred to have covert means and to conduct combined military and non-military operations.

A deeper problem with the concept is that it is more about tactics than strategy. Strategic thinking must include not only the capabilities of forces but also the characters of forces. Professional armies do “estimate of situation” formally for over a century and it includes mission, friendly forces, terrain, weather, technologies and enemy. Estimation of just enemy includes strength, intentions, morale, technologies and tactical capabilities Strategy, as it has been already implemented by armies, should cover, at a minimum, all the factors in the “estimate of situation. “Hybrid warfare instead, focuses on just the tactical capabilities of enemy, which disconnects from the enemy itself. Within this line of thinking, so many pet theories have been crammed into the military literature that it becomes nearly impossible to make a clear strategic thinking for anybody who adheres to the concepts like hybrid warfare (Cox et al., 2012).

Renz argue that hybrid warfare gained such a popularity that it became a concept counterproductive to decision making and strategic thought. It might be useful to highlight Russia’s new approach in Crimea, when compared to its less successful operations in Chechnya and Georgia, which were characterized by excessive use of force, outdated equipment and lack of coordination. However, it is not true to jump to the conclusion that Russia had found a ‘new art of war’ that made up for its shortcomings in conventional capabilities and posed a significant threat to the West. (Renz, 2016)

Hybrid war term blurs the distinctions within war, but it has the fatal risk of becoming another category, as it happened by Revolution in Military Affairs, an answer rather than the basis for questions. (Strachan, 2009) Every war is unique and requires its own logic. It is impossible to conduct the same strategy at every war. If we stick to a standard description (like hybrid warfare), we might have difficulty in understanding the character of war and the potential for change as each war is waged. It would not work for Russia elsewhere to use the same strategy she used in Crimea.

Echevarria resembles “hybrid warfare” to “blietzkrieg” of 1940s, a label that was never an official term in German Military Doctrine, but polished by media and commentators. In fact, what makes Germans successful in 1940s and Russians in 2014-2015 was not to create new conceptions of war, what makes them successful was conducting the main principles of war; recognizing their enemies correctly, then developing campaign plans that avoiding the strengths and exploiting the weaknesses of adversaries. (Echevarria, 2016) Although Hoffman states that his concept is consistent with the strategic theory, few analysts based their conclusions on Hoffmann’s specific understanding of the term and referred loosely to the general idea of ‘hybridity’. This resulted in widely varying understandings on what exactly hybrid warfare is. Analysts sometimes refer hybrid warfare to imply the complexity war, while sometimes just to note irregular activities in the war.

4. Labelling Russia-Ukraine conflict as a model for Hybrid Warfare

Although Russia does not define her actions in Ukraine as Hybrid Warfare nor has no intentions to do, it is merely a label attributed by West in an effort to understand the current warfare in Ukraine (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015).

Russia started her military modernization programme in 2008 and since then military spending has risen inexorably. Considering the program, one can claim that big investments in conventional capabilities shows Russia’s intention is to stay mostly traditional. Moreover, an extensive study on large exercises of Russia demonstrated that Russia is getting ready for largescale joint inter-service operations, instead of hybrid one. In other words, Russia does not take the hybrid warfare to the center of its military policy. (Renz, 2016) Russia has long recognized the need for using all power elements and arranged her official statements and national planning documents accordingly. For more than a decade, It has emphasized the West’s use of other power elements in conjunction with military operations. In 2010 Military Doctrine, the need for an integrated use of military forces and resources of a non-military character is cited and use of information is prioritized. In 2014 Military doctrine, Russia emphasized the participation of irregular armed forces and private military companies in military operations and the use of indirect and asymmetric methods of operations (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015).

However, these efforts performed by Russia are simply is an attempt to catch up the realities of contemporary warfare which U.S. and the West have been struggling in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere for over a decade. The West incorrectly identifies Russia’s actions to catch up modern characteristics of warfare as a new kind of warfare and assesses Russia’s particular operations in Ukraine as they are part of a coherent doctrine (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015). As NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg remarked in NATO Transformational Seminar in March 2015, Russia’s hybrid warfare can be seen as a “dark reflection” of comprehensive approach.

Some attributed the doctrinal thinking behind the Russian Hybrid War to the writings of General Valery Gerasimov, Russia’s Chief of General Staff. In an article in 2013 he wrote; “the very rules of war have changed significantly. The use of non-military methods to achieve political and strategic objectives has in some cases proved far more effective than the use of force… Widely used asymmetrical means can help neutralize the enemy’s superiority. These include the use of special operations forces and internal opposition to the creation of a permanent front throughout the enemy state, as well as the impact of propaganda instruments, forms and methods which are constantly being improved (Gerasimov, 2013).” Although he didn’t mention “hybrid warfare” or Ukraine in the article, later he was later identified as “the face of the hybrid war approach”.(Snegovaya, 2015) As Charles Bartles claimed in his article, Gerasimov’s emphasis on non-military tools was to describe ‘the primary threats to Russian sovereignty as stemming from US-funded social and political movements, such as color revolutions and the Arab Spring.(Bartles, 2016) Renz argued that one of Gerasimov’s central messages was to reproach Russian military leaders for not keeping up with contemporary strategic thought and as such for being in danger of falling behind the West.(Renz, 2016)

Russia’s operations in Ukraine are unique, because Russia had Sevastopol naval base and some forces in Crimea before war broke out. Additional agreements on transit of troops with already stationed forces in Ukraine enabled Russia to execute operations that otherwise would not be possible. Besides, mistakes of Ukrainian interim government such as declaring a possible change to the status of the Russian language and firing the Crimean Berkut (elite riot police) units provided available grounds for Russia(Kofman & Rojansky, 2015). In short, circumstances in Crimea provided a special opportunity for Russia to conduct operations which are not applicable elsewhere.

Another dimension of Russia’s hybrid war is information campaign. Russia’s use of broadcasting tools for propaganda as part of operations to annex Crimea has been defined a new and important tool by the West. One shouldn’t forget that, concerted use of Russian state-controlled media with operations is neither a new execution in Russia’s operations nor has it proven successful in the past. For instance, Russia utilized the information tools during 2004-2005 Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the 2008 Russia-Georgia War, but they weren’t effective enough. Even in Ukraine War, Russia had to intervene directly in the Eastern Ukraine, because propaganda was not formidable enough to gather sufficient pro-Russian forces to sustain an entirely indigenous uprising (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015). An extensive study done in eight European countries, moreover, concluded that the influence of Russian propaganda on mainstream media coverage in these states was ‘largely limited’ (Pynnöniemi & Rácz, 2016) Russia didn’t have to spend so much effort in Crimea in terms of information operations, due to Russian ethnic population. In other words, population were ready to take what Russia tried to impose.

Figure 2- Russian Military Presence in Crimea.

Figure 2- Russian Military Presence in Crimea.

http://www.newsweek.com/russias-putin-claims-authority-invade-ukraine-230622 (22 May 2016) Russia blockaded Ukrainian bases where it has a large military presence in the headquarters of its Black Sea Fleet.

There are number of lessons to be learned from Russia’s Crimea and Ukraine operation. However, they should not be exaggerated as implied by the proponents of hybrid warfare concept. It was obvious that this operation confirmed the effectiveness of Special Forces and command-control capability of Russia as she managed to coordinate different dimensions of state powers, such as regular forces, special operations forces, information operations including state media, elements of cyber warfare, deterrence and coercion through staged military exercises and the use of proxy fighters. The operation demonstrated that Russian military capabilities are far superior than Ukraine’s. But this doesn’t say much about her capabilities compared to other states. After all, modernization of Russia’s military is still ongoing and her conventional capabilities have not reached the level of deterrence against West yet. It is highly likely that she is going to refrain from an engagement with US and NATO in out-of-area operations beyond the post-Soviet space.(Renz, 2016)

To put it concisely, Russia achieved a swift victory against Ukraine because her strategy was successful. Favorable conditions in Crimea didn’t require to use mass forces. Russia assessed the situation very well and used appropriate means to achieve her policy ends. That’s called strategy. Focusing on Russia’s tactics and emphasizing “hybridity” as the determiner of the military success in Crimea obscure us to see realities on the ground and force us to respond Russia in a specific manner by losing flexibility. (Renz, 2016) It is important to ask; West and especially NATO, concentrating on the hybrid tactics of warfare, how ready would they be for the next round if a full conventional war is triggered by Russia?

5. Categorization of Warfare Might Not Be Helpful, But Strategy is Eternal.

According to Gray, most of the new strategic theories and ideas presented as new and innovative are locatable in classics- especially in the books of Clausewitz, Sun Tzu and Thucydides. He argues Americans rediscovered the counterinsurgency in the 2000s and realized that they are committed to hybrid warfare. Nowadays, NATO aligns itself with a position that defines hybrid threats as its main challenges. But one needs to remember that from US’ Vietnam War in Southeast Asia in the 1960’s and 1970’s (Gray, 2010) to Peloponnesian War in the fifth century BC or from Sino-Japanese War between 1937 and 1945 to Second World War, wars have hybrid character.

In almost every war; there is some irregularity, regularity and hybridity. It’s not reasonable and helpful for a defense planner to categorize warfare if not misleading. Gray believes that it is an error to divide challenges, threats, war, and warfare into categories—irregular, traditional (regular, conventional) or hybrid. (Gray, 2012) Categorization makes us enculturate the related new doctrine and respond in the category, hence lose initiative. Hew Strechan claims labelling warfare (major war, small war; regular war, irregular war; manoeuvre war, counterinsurgency operations; peacekeeping operations, peace enforcement, etc.) creates an expectation that war will not change its character during its course. If it does, however, there is a risk of being late to understand that the war jumped from one category to another (Strachan, 2009).

Poor description of Russia’s war in Ukraine as Hybrid War has already led Western analysts and policymakers down an unhelpful path. It seems that West attempts to alleviate the effects of long-term neglect of Russia, but this result in grouping everything Russia does under one rubric (Kofman & Rojansky, 2015), hence losing strategy. It is important to understand how Russia use national power elements in harmony, but the real lesson to learn from Russia-Ukraine conflict is not to discover a new model of warfare, real lesson is to learn how to deal with a major power like Russia when it can employ its almost full range of national power and can be successful at deploying large troops in short durations.

The Hybrid war term blurs the distinctions within war, but it has the fatal risk of becoming another category, as it happened by Revolution in Military Affairs, an answer rather than the basis for questions (Strachan, 2009). As Clausewitz stated in his classical work On War, “War is more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case”. Every war has its own characteristics while the nature of warfare is eternal. If we stick to a standard description (like hybrid warfare), we might have difficulty in understanding the character of war and the potential for change as each war is waged.

Figure 3- Enduring Military Strategy

Figure 3- Enduring Military Strategy

http://blogs.lexisnexis.co.uk/futureoflaw/2014/11/what-can-lawyers-learn-from-military-strategy (22 May 2016)

Looking back through the history of warfare, one can understand that most of the time, failures or defeats at war stem from the strategic incompetence. In the end, it is poor understanding of policy, strategy and war that cause the real problem. Bernard Brodie summarizes very well how main actors in Second World War were far from relating the war to the political aims and how they were interested so much in winning the war rather than aim of war (Brodie, 1959). Therefore, it is crucially important for strategists, defense community, political and military leaders to understand policy, strategy, war and relationship between them. History has full of examples of misunderstanding. For instance; many military thinkers believed that notion of RMA possibly made military and political leaders blind to focus on political objective of war. RMA efforts conducted in last thirty years left the military unprepared for the challenges in Iraq, caused the military to be poorly trained for anything other than high-intensity inter-state warfare. It was strategic incompetence that caused the failure of US in Iraq rather than irregularity of war. While strategy entailed the simultaneity of combat and stability operations, US adopted a phased approach in Iraq in 2003, focused on combat operations at the expense of stability operations.

Gray believes that there is only a single theory of strategy[**] which is universal and eternal, and the general theory of strategy provides the high-level conceptual guidance that we need in order to tailor our strategic behaviour to the specific case at issue. (Gray, 2012) Strachan claims that unitary view of war is becoming the gold standard, on the other hand, the binary view of war – major war versus small war – creates a false polarity, which can impede the understanding what is really going on (Strachan, 2009).

Nothing essential changes in the nature and function (or purpose) of strategy and war. However, there is widespread error in defense community that many confuse tactics with strategy and mistake changes in the character of events with the changes in their nature. Gray believes that best definition of strategy was described by Clausewitz so far and his definition is vital to understanding nature of eternal strategy. Clausewitz defines strategy as “the use of engagements for the object of the war”. Accepting Clausewitz definition is superior one, Gray himself defines strategy as “the use that is made of force and the threat of force for the ends of policy.” For Gray, anyone who understands Clausewitz’ definition wouldn’t be confused about what is strategic and what is not. While the tactics is armed forces or any instrument of power in action, strategy is the use of those instruments to policy goals. He moves one step further and claims that this definition and general strategic theory is applicable to the other so-called types of warfare like small wars or irregular warfare. (Gray, 1999) You can add hybrid warfare to this list. Following might be a good summary of this part.

“War is war and strategy is strategy.[***] Forget qualifying adjectives: irregular war; guerrilla war; nuclear war; naval strategy; counterinsurgent strategy. The many modes of warfare and tools of strategy are of no significance for the nature of war and strategy. A general theory of war and strategy, such as that offered by Clausewitz and in different ways also by Sun Tzu and Thucydides, is a theory with universal applicability. Because war and strategy are imperially authoritative concepts that accommodate all relevant modalities, a single general theory of war and strategy explains both regular and irregular warfare. Irregular warfare is, of course, different from regular warfare, but it is not different strategically. If one can think strategically, one has the basic intellectual equipment needed in order to perform competently in either regular or irregular conflict. Needless to add, understanding and performance are not synonymous.“(Gray, 2006)

6. Conclusion

Since the end of Cold War, as a result of numerous attempts to understand complex security environment, many definitive terms and doctrines has emerged. As a superpower which has the largest military complex and defense community in the world, most of the innovative terms originate from US. According to Gray, this stem from US’ cultural tendency to theorize about military affairs. The American marketplace for strategic, military, and other security ideas is very much larger than anywhere else on the planet. Career advancement plans, competition between ideas, the scale of the particular national context for intellectual argument causes producing too many strategic theories. As old ideas are coined or rediscovered, and as they are proliferated carelessly, the core meaning of the subject of strategy can slip away. Competitions in the American defence community marketplace produce successive waves of concepts and proposals, as the hot topics of the day rise, peak, decline, and then all but vanish from sight until they reappear in somewhat different forum a few years later. (Gray, 2012)

Proponents of the hybrid warfare claim that it serves the purpose of understanding of contemporary and future warfare. However, as this study advocated, it includes so many types of warfare that every conflict fits into the definition somehow. Furthermore, hybrid threats are defined as mystical adversaries that could conduct all types of warfare simultaneously. An official strategist or a defence planner would really have difficulty in building strategy, if he chose to understand modern warfare through hybrid warfare concept.

Today, many statesmen, strategists, defence planners and military people has been trying to understand what this new term-hybrid warfare really means, how it will affect the way our armies fight and how it will shape the posture and capabilities our armed forces. They might be losing their valuable time by trying to understand a new concept while what they are looking for is actually in the classics of general war theory. It might be much more helpful to implement the rules of eternal strategy instead.

“Knowing the enemy” for instance, is one of the integral rules of eternal strategy in every era. Just knowing the enemy, if it is performed properly, and sticking to the cardinal rules between policy, war and strategy would be enough to understand contemporary conflicts and meet the challenges appropriately. We would not need a new term, like hybrid warfare to be successful on defending our countries.

Russia might be using information war, propaganda or some covert methods to annex some part of another country. Knowing Russia’s priorities and new methods instead of delving into some poor concepts would provide much of the tools to counter her offense. Interpreting Russia’s or other adversaries’ new tactical methods in a new concept, as Hew Strachan put it rightly, creates an expectation that today’s warfare will happen in the context of this concept and not change its character in its due course. If it does, however, there is a risk of being late to understand that the war jumped from one category to another. In other words, if Russia for instance, chooses to conduct a pure conventional war against a major power, strategists and soldiers might be caught off their guard.

Gray claims that it is an error to divide challenges, threats, war and warfare into exclusive categories. (conventional, irregular or hybrid) By categorization, the big picture tends to be replaced by particular aspects of whole conception. Difficulty does not lie in the core meaning of these concepts. Rather the problem is the misunderstanding of these concepts, as they became decontextualized from strategic thinking through familiarity. Categorization on the other hand, encourages us to respond in category, causing the loss of initiative. Indeed, Russia’s activities in Crimea and Ukraine implies important lessons to be learned. However, defense communities are so concentrated on hybrid warfare concept that most analysts are busy for detecting how the forces were blurred or how Russia conduct covert operations and propaganda. They are looking the current conflict through the hybrid warfare concept. Russia’s grand strategy, military strategy and capabilities are not discussed adequately as they should.

Despite all its deficits, the latest buzz word, hybrid warfare, seems to be adopted by the world’s leading countries and NATO even in their official planning documents. Defence communities are in the midst of building strategies against hybrid threats. However, there are good reasons to be doubtful about hybrid warfare.

References:

Bartles, C. (2016). Getting Gerasimov Right. Military Review, (January-February), 30–38.

Brodie, B. (1959). Strategy in the Missile Age. Princeton University Press. New Jersey.

Chalupa, A. (2013). How to Explain What’s Happening in Ukraine. Retrieved August 15, 2015, from http://ideas.time.com/2013/12/17/how-to-explain-whats-happening-in-the-ukraine/

Cox, D. G., Bruscino, T., & Ryan, A. (2012). Why Hybrid Warfare is Tactics Not Strategy: A Rejoinder to “Future Threats and Strategic Thinking.” Infinity Journal, 2(2), 25–29.

Echevarria, A. J. (2016). Operatinging the Gray Zone: An Alternative Paradigm For U.S. Miltary Strategy. Strategic Studies Institute U.S.A.W College Press.

Eve, H., & Piret, P. (2015). The Challenges of Hybrid Warfare. International Centre for Defence and Security Analysis.

Gerasimov, V. (2013). The Value of Science in Anticipation. Military Industrial Courier, 8(476). Retrieved from http://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632

Gray, C. S. (1999). Modern Strategy. Oxford University Press.

Gray, C. S. (2006). Irregular Enemies and the Essence of Strategy: Can the American Way of War Adapt? Retrieved from U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute.

Gray, C. S. (2010). The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice. The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579662.001.0001

Gray, C. S. (2012). Categorical Confusion ? the Strategic Implications of Recognizing Challenges Either As Irregular or Traditional.

Heidi, R., & Aleksandr, G. (2015). Russia’s Hybrid Warfare.

Hoffman, F. G. (2007). Conflict in the 21 st Century : The Rise of Hybrid Wars. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from http://www.potomacinstitute.org/

Hoffman, F. G. (2009). Hybrid vs. Compound War, The Janus Choice: Defining today’s Multifaceted Conflicts. Armed Forces Journal, (October).

Jacobs, A., & Lasconjarias, G. (2015). NATO’s Hybrid Flanks, Handling Unconventional Warfare in the South and the East. NATO Defense College, (112).

Kofman, B. M., & Rojansky, M. (2015). A Closer look at Russia ’ s “ Hybrid War .” Kennan Cable.

Korchemkin, M. (2014). East European Gas Analysis. Retrieved August 16, 2015, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/interactives/ukraine-conflict-in-maps/

Linn, B. M. (2007). The Echo of Battle- The Army’s Way of War. Harvard University Press.

Murray, W., & Mansoor, P. R. (2012). Hybrid Warfare- Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present. Cambridge University Press.

NATO Foreign Ministers Address Challenges to the South, Agree New Hybrid Strategy and Assurance Measures for Turkey. (2015). Retrieved May 7, 2016, from http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_125368.htm%0A

NATO Transformation Seminar. (2015). In White Paper- Next Steps in NATO’S Transformation: To the Warsaw Summit and Beyond. Washington.

Poli, F. (2010). An Asymmetrical Symmetry: How Convention Has Become Innovative Military Thought. US Army War College.

Pynnöniemi, K., & Rácz, A. (2016). Fog of Falsehood- Russian Strategy of Deception and the Conflict in Ukraine. Helsinki. Retrieved from http://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/588/fog_of_falsehood/

Renz, B. (2016). Russia and “hybrid warfare.” Contemporary Politics, 22(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201316

Snegovaya, M. (2015). Putin’s information warfare in Ukraine: Soviet origins of Russia’s hybrid warfare.

Stoker, D. (2016). What’s in a Name II: “Total War” and Other Terms that Mean Nothing. Infinity Journal, 5(3), 21–23.

Strachan, H. (2009). One War, Joint Warfare. The RUSI Journal, 154(4), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071840903216437

Ukraine crisis: Timeline. (2014). Retrieved August 16, 2015, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-26248275

Ukraine Crisis in Maps. (2015). Retrieved August 16, 2015, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27308526

Whitmore, B. (2015). Is This the End of Ukraine’s Peace Process? Retrieved August 16, 2015, from http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/08/russia-ukraine-conflict-minsk-ceasefire-passports/400505/

[**] Gray explains the theory in Modern Strategy and Strategy Bridge. He bases the theory on mostly the works of ten authors; Carl Von Clausewitz, Sun Tzu, Thucydides, Machiavelli, Jomini, Liddell hart, J.C. Wylie, Edward N. Luttwak, Bernard Brodie and Thomas C. Schelling. He describes seventeen never-changing dimensions of eternal strategy in Modern Strategy, while he presents the theory in the form of twenty-one dicta in Strategy Bridge.

[***] Many academicians and soldiers state this phrase in recent years “War is war”. See Williamson and MANSOOR Peter R., Hybrid Warfare- Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p.1 Sir Richard Danna, as Chief of the British General Staff, made exactly this point in his lecture, ‘A Perspective on the Nature of Future Conflict’, delivered at Chatham House on 15 May 2009., Vincent Desportes, director of the Collège Interarmées de Défense in France, Tomorrow’s War: Thinking Otherwise (Washington DC: Brookings, 2009), p. 115.