Murat Caliskan* – Paul Alexander Cramers**

Hybrid warfare is the latest of the terms/concepts that have been used within the defense community in the last three decades to label contemporary warfare. It has been officially adopted in the core strategic documents of NATO, EU and national governments and has already inspired many articles, policy papers and books. However, hybrid warfare is a concept as controversial as it is popular. Frequently criticized for being ambiguous and weak as a concept, it carries the risk of misleading the defense community and obscuring the sound strategic thought. Carrying out a content analysis over 66 media items, this study has demonstrated that hybrid warfare is indeed an ambiguous concept. It is revealed that the authors used hybrid warfare term in its true meaning only 20 (30%) media items. Most of the time (70%), the authors imply another concept when they use hybrid warfare. We believe, it is high time that international defense community built consensus over the actual meaning of hybrid warfare.

Key Words: hybrid warfare, content analysis, Russia-Ukraine Conflict, military concepts, military doctrines.

“Hybrid warfare” is one of the most widely used terms to explain or imply contemporary warfare. The term has gradually gained traction since its first use in 2005. Popularised by Hoffman (2007), it has almost become the “new orthodoxy” in military thought (Poli, 2010). Before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the term was referenced widely as a model for contemporary warfare in defence community. However, with Russia’s operations in Ukraine, it has begun to be cited frequently as a “new kind of warfare”, circulating in distinct fora from newspapers to official strategic documents. It is frequently cited in media and even found a place in the official documents of the EU and NATO.

NATO’s adoption of the term had a huge effect on its popularity. NATO agreed on a strategy to counter hybrid warfare at the end of 2015 (NATO Foreign Ministers Meeting, 2015) as a continuation of its decision at the Wales Summit in 2014. At the Warsaw Summit in 2016, NATO announced its determination to address hybrid threats (NATO-Warsaw Summit Communiqué, 2016). A few months later, the EU developed a “joint framework”, focusing on its response to hybrid threats. Based on this framework, it established a Hybrid Fusion Cell within the Intelligence and Situation Centre (INTCEN), created two StratCom (Strategic Communication) task forces against disinformation and established The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in Finland in 2017. The EU Global Strategy envisaged close cooperation with NATO on countering hybrid threats. A recent report on NATO-EU cooperation, developed through interviews with NATO-EU officials, identifies hybrid threats as a major challenge (Raik & Järvenpää, 2017).

Many analysts and academics have attributed the doctrinal thinking behind the Russian hybrid war to the thoughts of General Valery Gerasimov, Russia’s Chief of General Staff. In an article in 2013, he wrote: “the very rules of war have changed significantly. The use of non-military methods to achieve political and strategic objectives has in some cases proved far more effective than the use of force… Widely used asymmetrical means can help neutralize the enemy’s superiority. These include the use of special operations forces and internal opposition to the creation of a permanent front throughout the enemy state, as well as the impact of propaganda instruments, forms and methods which are constantly being improved.” (Gerasimov, 2013) Although he didn’t mention “hybrid warfare” or Ukraine in the article, he was later considered as “the face of the hybrid war approach” by many Western analysts. (Snegovaya, 2015) However, Gerasimov’s emphasis on non-military tools was aimed at describing the primary threats to Russian sovereignty, which had stemmed from the perceived US-funded social and political movements, such as color revolutions and the Arab Spring (Bartles, 2016). One of Gerasimov’s central messages was to reproach Russian military leaders for not keeping up with contemporary strategic thought and for being in danger of falling behind the West, rather than laying the foundation for a new military approach (Renz, 2016).

The amount of criticism towards the concept has been increasing along with its popularity. One of the main critiques about hybrid warfare is its ambiguity and weakness as a concept. According to this line of thinking, hybrid warfare is too inclusive to be analytically useful(Gray, 2012). Any violence can be labelled “hybrid” as long as it doesn’t have the characteristics of a single form of warfare. This causes the term to lose its value as an analytical tool to approach modern warfare. In some cases, this ambiguity makes it a convenient label to describe all the issues that we currently do not understand regarding the changing character of warfare (Puyvelde, 2015). Hybrid warfare became a catchall concept that allows “grouping everything Moscow does under one rubric”(Kofman & Rojansky, 2015). It became such an inclusive term that even the public statements made by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov can be labelled as hybrid warfare when he criticized the German police for the lack of transparency with regards to the alleged rape of a 13-year old Russian girl in Berlin (Renz & Smith, 2016). This broadness caused both Russia’s war in Ukraine and Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL)’s war in Syria to be grouped under the same category as a model for hybrid warfare. It is because of this ambiguity that the term has been used frequently but suggesting different meanings. Many analysts loosely refer to hybridity, but usually imply different meanings already (well known and defined under other labels/terms) simply such as ‘irregular warfare’, ‘propaganda’, ‘information warfare’ etc.

Therefore, we believe that it is important to inquire the soundness of hybrid warfare concept as it has already been adopted in core official documents. This study aims to understand whether the hybrid warfare concept is ambiguous or not through exploring what is really meant by different stakeholders when they use hybrid warfare. To achieve this goal, a content analysis was carried out on 66 news articles to reveal the real meaning behind the term. We need to note that this paper presents initial results of a broader study, which aims to analyse all media coverage from 2014 to date. Although 66 items are sufficient to formalize our thoughts, further analysis on a larger sample size would provide more robust and in-depth knowledge on the research topic. The first part of this paper presents various definitions of hybrid warfare and determines the definition to be used throughout this study. Besides, the definitions of some terms that are widely associated with hybrid warfare are provided. We believe that it is important to understand the definitions and the meanings of the terms for the consistency, objectivity and the reliability of this study. The second part explains the methodology, the sampling and the process of data collection. Lastly, the third part presents research findings and discusses the results.

1. Definitions of Hybrid Warfare and Frequently Used Terms

Hoffman defined hybrid threats as “a full range of different modes of warfare including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder.” (Hoffman, 2007) For Hoffman, hybrid wars can be conducted by both states and a variety of non-state actors, by separate units, or even by the same unit, but operationally and tactically directed within the main battlespace to achieve synergistic effects both in the physical and psychological dimension of conflict. (Hoffman, 2007)

NATO members agreed in the Transformation Seminar-2015, held in Washington DC that “hybrid warfare and its supporting tactics can include broad, complex, adaptive, opportunistic and often integrated combinations of conventional and unconventional methods. These activities could be overt or covert, involving military, paramilitary, organized criminal networks and civilian actors across all elements of power.” (‘NATO Transformation Seminar’, 2015) The EU has broadly defined hybrid threats as a “mixture of coercive and subversive activity, conventional and nonconventional methods (i.e. diplomatic, military, economic, technological), which can be used in a coordinated manner by state or non-state actors to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the threshold of formally declared warfare” (Maas, 2017). Although both definitions are similar to Hoffman’s definition, there is an increasing emphasis on the broader aspects of strategy other than military, such as diplomacy, economy and technology. This is more obvious in the description of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare given by the 2015 issue of the Military Balance: “the use of military and non-military tools in an integrated campaign designed to achieve surprise, seize the initiative and gain psychological as well as physical advantages utilizing diplomatic means; sophisticated and rapid information, electronic and cyber operations; covert and occasionally overt military and intelligence action; and economic pressure.” (“Military Balance,” 2015)

One can easily conclude that with Russia’s war in Ukraine, the definition of the concept became more inclusive and tends to focus more on non-military factors, such as information warfare, propaganda, cyber security, subversive and non-kinetic means, while Hofmann’s definition was more about military issues and the convergence of different modes of warfare.

However, what is common in both Hoffman’s approach and later approaches is the simultaneous use of military and non-military tools. For any conflict to be named as hybrid warfare, it requires for either a state or a non-state actor to employ the integrated use of military and non-military (conventional-unconventional, hard-soft) tools to achieve a policy goal. In this study, any article that interprets the concept of hybrid warfare as a combination of military and non-military tools to achieve policy goals was accepted as a true approach.

Critiques of the concept argue that hybrid warfare usually refers to different meanings other than this hybridity. Furthermore, those terms that are usually referred have overlapping definitions as well. For instance, it is not easy to differentiate the meanings of information warfare, propaganda, subversive warfare or political warfare. To set a common understanding throughout the study, the definitions of widely used terms associated with hybrid warfare are presented in the following paragraphs.

Comprehensive Approach was defined as “blending civilian and military tools and enforcing co-operation between government departments, not only for operations but more broadly to deal with many of the 21st century security challenges, including terrorism, genocide and proliferation of weapons and dangerous materials” in the UK House of Commons Defence Committee report; (UK House of Commons Defence Committee, 2010) In a Chatham House paper, a broader approach including international actors is presented as the following: “the comprehensive approach is the cross-governmental generation and application of security, governance and development services, expertise, structures and resources over time and distance in partnership with host nations, host regions, allied and partner governments and partner institutions, both governmental and non-governmental.” (Lindley-French, Cornish, & Rathmell, 2010) NATO also suggests that “addressing crisis situations calls for a comprehensive approach combining political, civilian and military instruments. Military means, although essential, are not enough on their own to meet the many complex challenges to our security. The effective implementation of a comprehensive approach to crisis situations requires nations, international organisations and non-governmental organisations to contribute in a concerted effort. (‘NATO Topics: A “comprehensive approach” to crises’, 2018) Many analysts define hybrid warfare as “the comprehensive approach in the offense”. As NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated in NATO’s Transformational Seminar, Russia’s hybrid warfare can be seen as a “dark reflection” of comprehensive approach. According to this line of thinking, the difference between comprehensive approach and hybrid warfare lies in the aim. Comprehensive approach aims to build or to strengthen the governance, whereas hybrid warfare aims to weaken it. Another term that could be associated with both hybrid warfare and comprehensive approach is full-spectrum warfare. Indeed, a closer look on definitions shows that these terms are the same in their essence.

Political Warfare, in Kennan’s definition, is the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, in times of peace, to achieve its national objectives. Tools used in political warfare are non-kinetic in nature, whereas hybrid warfare connotes the combination of non-kinetic and conventional military means (Robinson et al., 2018). Political warfare includes all the tools of national power: diplomatic, informational, military, and economic. However, differently from hybrid warfare, especially military tools have unconventional characteristics, such as supporting proxy forces, providing conditional military aid to a state etc. In this study, hybrid warfare is rather labelled as “political warfare” when the author implied all diplomatic, economic, informational and military activities short of war rather than the combination of kinetic and non-kinetic activities.

Irregular Warfare is a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population. Irregular warfare favours indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities, in order to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will” (Irregular Warfare Joint Operating Concept, 2007) What makes irregular warfare different is the focus of its operations – a relevant population – and its strategic purpose – to gain or maintain control or influence over, and support of, that relevant population. In other words, the focus is on the legitimacy of a political authority to control or influence a relevant population. (Irregular Warfare Joint Operating Concept, 2007) According to the DoD Defense Directive Number 3000.07 (dated August 28, 2014), irregular warfare includes: “any relevant DoD activity and operation such as counter-terrorism; unconventional warfare; foreign internal defense; counterinsurgency; and stability operations that, in the context of irregular warfare, involve establishing or re-establishing order in a fragile state or territory” (‘Joint Special Operations University Library’, 2018).

Unconventional Warfare is a broad spectrum of military and paramilitary operations, normally of long duration, predominantly conducted through, with, or by indigenous or surrogate forces who are organised, trained, equipped, supported, and directed in varying degrees by an external source. It includes, but is not limited to, guerrilla warfare, subversion, sabotage, intelligence activities, and unconventional assisted recovery (Joint Publication 1-02, 2001). Unconventional warfare is composed of activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area. Unconventional Warfare is one of the five main activities identified under Irregular Warfare (‘Joint Special Operations University Library’, 2018).

Subversive Warfare: subversion is an “action designed to undermine the military, economic, psychological, or political strength or morale of a regime”, according to the DoD Dictionary of Military Terms (Joint Publication 1-02 Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2001). This is quite similar to the definition of unconventional warfare. It is noted in the same dictionary that “anyone lending aid, comfort, and moral support to individuals, groups, or organizations that advocate the overthrow of incumbent governments by force and violence is subversive and is engaged in subversive activity.” Furthermore, the dictionary maintains that “all willful acts that are intended to be detrimental to the best interests of the government and that do not fall into the categories of treason, sedition, sabotage, or espionage will be placed in the category of subversive activity.”

All three terms -irregular warfare, unconventional warfare, subversive warfare- are quite similar concepts in that they postulate the use of a broad spectrum of military and non-military capabilities by non-state actors to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow an established government. The main difference lies in their scope. Irregular warfare has the broadest meaning as it suggests the general notion of warfare between state and non-state actors and, in addition to unconventional warfare, it includes activities such as counter-terrorism, counter-insurgency and stability operations. Similarly, unconventional warfare has a broader meaning than subversive warfare because it contains more instruments than subversive activities such as guerrilla warfare, sabotage, intelligence activities, and unconventional assisted recovery. Subversive activities, as is suggested in the Cambridge dictionary, connotes the attempts to change or weaken a government by working secretly within it, which has the same aim with irregular warfare and unconventional warfare, but with more subtle methods through undermining social and moral integrity. Irregular warfare and unconventional warfare are similar to hybrid warfare as they assume the use of a combination of military and non-military tools; however, on the contrary, they suggest a struggle between a state and a non-state actor whereas hybrid warfare can be employed by both state or non-state actors. Subversive warfare, on the other hand, has the same goal with these two concepts, but less depends on direct military tools. All three concepts have common aspects with propaganda-psychological warfare-information warfare in the sense that the focus of their operations is to influence the relevant population. However, later three terms are only one tool -though very important- among others that are used in irregular, unconventional or subversive warfare.

Information warfare is the conflict between two or more groups in the information environment (Porche III et al., 2013). While there is not an official definition of “information warfare” in U.S. military doctrines, the Secretary of Defense characterizes “information operations” as the integrated employment, during military operations, of information-related capabilities (IRCs) in concert with other lines of operation to influence, disrupt, corrupt, or usurp the decision making of adversaries and potential adversaries while protecting our own (Joint Publication 3-13, Information Operations, 2014). Information warfare aims to use the information itself as the weapon. It is possible to use a broad range of tools to conduct information warfare, as it is inherently multidisciplinary and multidimensional. Cyber capabilities are just one of many tools use to carry out that task.

Cyber warfare has a more technical and narrower meaning and focuses on disrupting and disabling the computer and cyber systems themselves. It doesn’t represent a warfare alone but is rather a tool used in a broader warfare concept. In most articles, propaganda-psychological warfare or information warfare is used together with cyber warfare, because they are closely related. Since cyber warfare is only a tool in the realization of these concepts, throughout this study, the term will not be taken as a separate label for warfare.

Propaganda is defined as “any form of communication in support of national objectives designed to influence the opinions, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any group in order to benefit the sponsor, either directly or indirectly (Joint Publication 1-02, 2001). For Taylor, it is “the conscious, methodical and planned decisions to employ techniques of persuasion designed to achieve specific goals that are intended to benefit those organizing the process” (Taylor, 1995).

Psychological Operations are the planned operations to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behaviour of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals. The purpose of psychological operations is to induce or reinforce foreign attitudes and behaviour favourable to the originator’s objectives. Also called PSYOP (Joint Publication 1-02, 2001).

As the definitions demonstrate, propaganda, psychological operations or information warfare are closely linked and there is no big difference between the meanings of these terms. In summary, all three concepts focus on influencing opinions, emotions, and motives of a target audience. For this reason, these terms are frequently used interchangeably. It can be said that the information warfare has somewhat a broader meaning as it comprises the use of information-related capabilities additionally, even though the essence of the term is almost the same. For Tiina, it was because of the negative connotation of the term “propaganda” that psychological warfare was began to be used instead (Seppälä, 2002). The same explanation is valid for the use of information warfare when psychological warfare had a negative connotation as well. Another reason for the use of information warfare might be the increasing interdependency of communications systems with other infrastructures. Because of this similarity in the meanings of three concepts, we preferred the latest term, “information warfare” as the representative of this trio of terms.

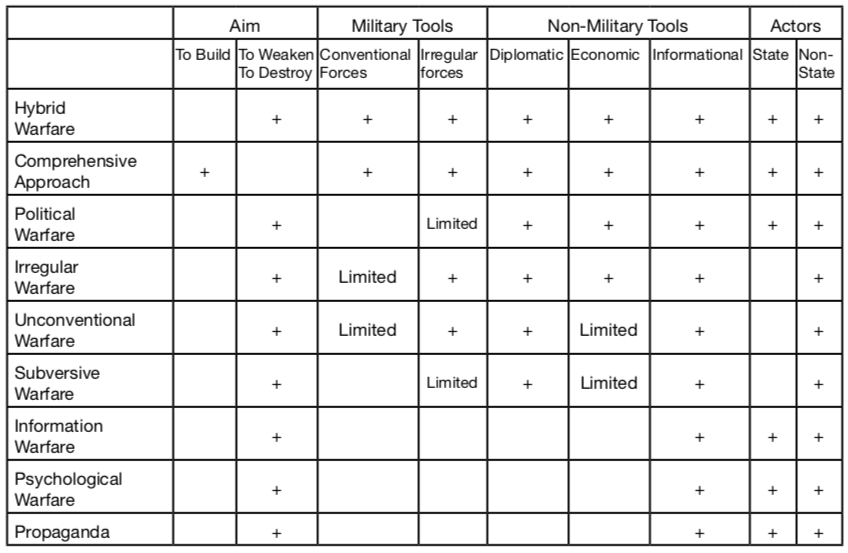

Table_1 below depicts the comparison of above-mentioned terms based on some prominent characteristics of warfare to provide an easier understanding.

Table 1- Comparison of various concepts

It would be possible to say that all definitions have some overlapping aspects. To put it into a simpler frame, hybrid warfare is the most inclusive phenomenon of all the terms which requires the simultaneous use of both military and non-military tools, by either state or non-state actors. Comprehensive approach has a very close meaning, which differs only in the aim. Political warfare postulates the use of all non-military tools, although it may entail the use of military tools such as proxy forces and special forces from time to time. Irregular warfare and unconventional warfare are similar to hybrid warfare in that both include the use of a broad range of military and non-military tools, but in a different context, which is in a non-state actor’s fight against a state actor. Although subversive warfare is also similar to irregular and unconventional warfare, the tools used in subversive warfare are more limited. Propaganda, psychological warfare or informational warfare have also many common aspects with other terms, especially in the sense that the main goal is to influence the perception of the relevant population. However, the latter three terms constitute only one tool of broader warfare concepts such as hybrid warfare or political warfare, which postulate the use of all non-military tools.

2. Methodology and data collection

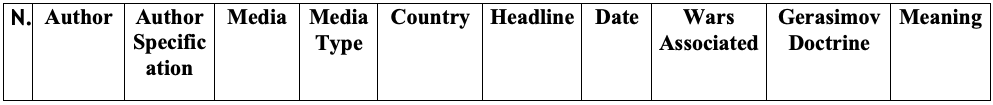

“The content analysis” has been used to examine 66 number of news articles in this paper. The content analysis refers to any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages (Holsti, 1969 as cited by Bryman, 2012). It is an approach used to analyse documents and texts that seeks to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories and in a systematic and replicable manner (Bryman, 2012). For an objective and a systematic research, ten categories are predetermined and defined (Figure 1). Since the main objective of this paper is to understand whether hybrid warfare is used in tune with its actual meaning and to reveal what is really meant by the term hybrid warfare, it can be said that “the meaning” category is the most important one. All the terms that could be applied to this category have been defined in the previous section. This gives us the opportunity to determine what the authors really mean when they used hybrid warfare in an objective and systematic manner. As it can be seen in Figure 1, apart from the meaning of hybrid warfare, other categories such as the authors and the authors’ qualifications, the media and the media types, the country and the date where and when the article was published, the wars that are clearly associated with hybrid warfare, and whether the author associates the term with Gerasimov Doctrine are examined as well.

Figure 1_ Coding schedule

Figure 1_ Coding schedule

Data collecting has been carried out through the mixture of three different methods. In the first method, we used 32 news articles that we have accumulated in our personal archives since Russia’s invasion of Crimea. In the second method, we entered the term “hybrid warfare” in the Google search bar and examined first 11 news articles in the results. In the third method, we focused on some global and regional news magazines, newspapers and the media outlets such the Economist, the Newsweek, the Foreign Policy, Le Monde, Le Figaro, Le Point, Paris Match, which have an impact on the people who are interested in the world’s political and security affairs. In this method, we examined 23 items written in English or French.

Out of ten categories, which are shown in Figure 1, the only category that requires interpretation is the “meaning” category. As a principle, we examined the literal meaning of hybrid warfare without paying attention to whether the overall discussion in the article is valid or not. In some articles, the authors clearly stated what they mean by hybrid warfare. For instance, Paul J. Saunders, a former official in the U.S. State Department and executive director of The National Interest, -a Washington, D.C.-based public policy think tank, stated that “Hybrid warfare -the term applied to Russia’s particular approach to irregular warfare in Ukraine- is the threat du jour in international security affairs” in his article in 2015. In this case and in similar cases, we directly noted the term he used down to the meaning category, as he clearly sees hybrid warfare as a type of irregular warfare. No interpretation is required.

Some articles require more cautious interpretation. For instance, Peter Pindjak stated in 2014 in his article written for NATO Review Magazine, “As the conflict in Ukraine illustrates, hybrid conflicts involve multilayered efforts designed to destabilise a functioning state and polarize its society. Unlike conventional warfare, the “centre of gravity” in hybrid warfare is a target population. The adversary tries to influence influential policy-makers and key decision makers by combining kinetic operations with subversive efforts.” [emphasize added] (Pindják, 2014) The author implies “propaganda-psychological operations-information warfare” by using phrases such as “destabilize a state”, “polarize a society”, “influence policy-makers”. He also states, “combining kinetic operations with subversive operations”, which is a somewhat accurate definition of hybrid warfare. However, assessing the essence of the whole text, we can infer that the main emphasis of the author is on the propaganda-psychological operations-information warfare.

In some articles, the term is defined exactly as it is in the literature, namely as the simultaneous use of military and non-military means, but the author actually used the term to imply another term in the overall context of the text. In these cases, the term that the author really implies has been taken. Therefore, the research required a cautious reading of the whole text of the articles to understand what exactly meant by the author. For instance, Nolan Peterson begins his article, “How Putin Uses Fake News to Wage War on Ukraine”, with an example of how Russians used the text messages to influence Ukrainian military. Then, hybrid warfare is defined as “the combined use of propaganda and cyberwarfare to support military operations on the ground are hallmarks of Russian “hybrid warfare.”(Nolan, 2017) This definition, although it is not a totally true definition as it limits non-military means to only propaganda and cyberwarfare, could be accepted as somewhat true as it refers to a combination of military and non-military means. The author continues with General Breedlave’s speech where he defined the hybrid warfare as “the most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg”. Then he moves on to the Ukrainian President Poroshenko’s words: “Whether it is Ukraine, the EU, or the United States, Russia has the same playbook and goals. It employs hybrid warfare -so-called fake news, computer hacking, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, snap drills, direct military interventions, and so on and so forth- to undermine the Western democracies and break the transatlantic unity.” Although the author defines hybrid warfare somewhat accurately and does not directly associate hybrid warfare with another term, we can infer from the overall text that the author implies propaganda and information warfare when he uses the term “hybrid warfare”. Therefore, in this case, we compromised on the term “information warfare” as the term implied in this article.

Frequently, hybrid warfare is mistaken for political warfare, which is associated with almost all instruments short of war including military ones.

As it is mentioned above, military capabilities in political warfare are unconventional in nature whereas hybrid warfare requires the combination of conventional and unconventional forces. For instance, in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which is admitted as a model of hybrid warfare, Russia stationed its conventional forces ready to invade Ukraine at the border in addition to pro-Russian proxy forces in Ukraine. At a certain point, Russia even had to use its conventional fire-support against Ukraine forces. This is much more than supporting proxy forces or organizing resistance groups. Therefore, any article implying the use of all instruments short of war, including non-kinetic military units, will be labelled as “political warfare” unless it suggests any combination.

In some cases, the author used the term with no distinctive meaning. In other words, it is not possible to understand whether the author used the term in compliance with its true meaning or whether he implies another term. For instance, in his small commentary on the website of Carneige Europe, a global think tank, Andrew Michta stated “Russia’s application of hybrid warfare in eastern Ukraine is a recipe not so much for defeating Europe outright as for peeling the post-Soviet space away from the rest of the continent… So far, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hybrid war in Ukraine has achieved two fundamental goals… If Russia decides to jump NATO’s borders and, for instance, launch a hybrid campaign in one of the Baltic states, this will force the West to grapple with questions about NATO solidarity…”(Michta, 2015) He uses the term but with no apparent meaning. These cases are categorized with “no meaning” tag in this study.

Some authors do not clearly define the term or use it in a right way but imply the true definition in an indirect manner. For instance, Alexander Nicoll states “it is necessary to keep in mind that this is not just a military matter. Hybrid tactics seek to undermine the foundations of a state, so it is important that all states look to their foundations and attempt to deal with issues and divisions that could be exploited by an adversary -and that if necessary, they get help in doing this.” (Nicoll, 2015) In this commentary, Alexander does not directly use a definition that connotes a simultaneous use of military and non-military means. But he notes that hybrid tactics are activities to undermine the foundations of a state in addition to military activities. He doesn’t suggest a simultaneous use of both military and non-military tools or he doesn’t imply all non-military tools except from those undermining state foundations. However, he somehow suggests a combined use. Therefore, these kinds of cases are admitted as a correct use of the term as well.

3. Research Findings and Discussion

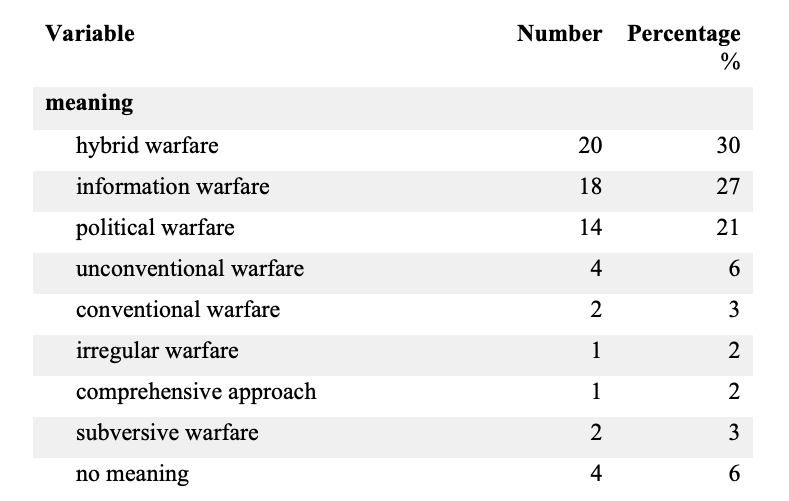

This study presents preliminary part of a broader project, which aims to examine all media coverage of hybrid warfare concept between 2014-2018. Although the current number of media items (66 at total) is limited and some subjects remained in shadow, we believe that it is sufficient to give an idea about the implications of the use of hybrid warfare, which is the main goal of this paper. Table-2 demonstrates the results regarding the “meaning” category.

Table 2- Results for the “meaning” category

The results show that in only 20 (30%) media items, the term “hybrid warfare” is used in its true meaning. In other items, the authors used the term “hybrid warfare” but they implied “information warfare” in 18 (27%) items, “political warfare” in 14 (21%) items, “unconventional warfare” in 5 (6%) items. The results clearly demonstrate that hybrid warfare is an ambiguous concept and is not clearly understood by different stakeholders in defense community. In other words, there is not an agreed definition or understanding. Most of the time (70%), the authors imply another concept when they use hybrid warfare.

These results suggest two potential reasons for the miscommunication. It is either because the authors have insufficient knowledge on military concepts or the concept is too weak to explain current events that the authors imply different meanings. We believe that both options are valid. For instance, hybrid warfare is confused with political warfare in 14 media items, which is understandable as there is a similarity between two terms. Although it is author’s responsibility to know the difference between two terms, big part of the problem stems from the broadness of the term. Hybrid concept has such an inclusive definition that it allows authors to label any conflict as hybrid warfare even when the conflict in question includes only some part of the all characteristics. However, mistaking hybrid warfare for information warfare is a clear indication of the authors’ lack of knowledge on military concepts as there is a clear difference between two terms.

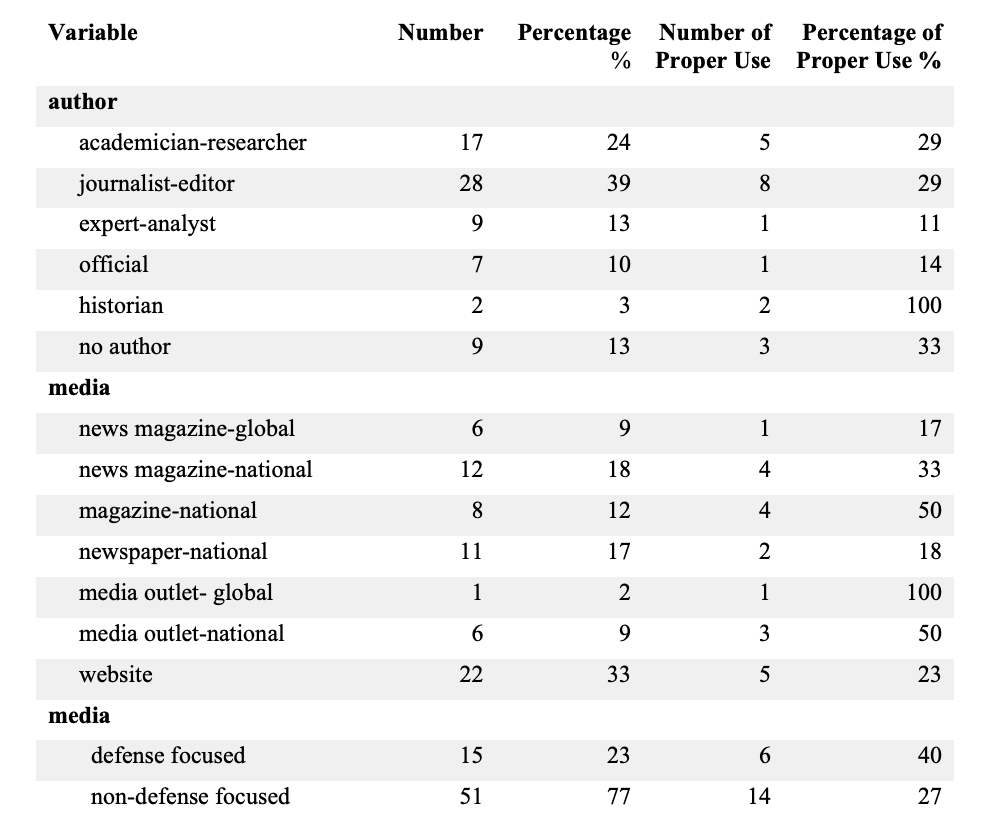

Table 3- The Results of “author”, “media type” and “country” categories

Table 3- The Results of “author”, “media type” and “country” categories

As it is shown in Table-3, there is no meaningful difference between academics and journalists in their capacity to use the term in its proper meaning. In both groups, only 29% of the population uses the term correctly, which is very close to the general average (30%). This ratio is even less in other groups, namely in experts or officials (11%-14%). Similarly, media types also do not suggest a meaningful difference in terms of correct use of the term. It is likely to infer in-depth implications if the sample size is enlarged. But current numbers do not suggest any implication.

Having said that, we could infer that defense focused media (40%) is better than non-defense focused media (27%) in using the term in a correct manner.

Table 4- The Results of “wars associated” and “Gerasimov Doctrine” categories

Regarding the examples of wars associated with hybrid warfare, there are two important issues that are worth to be discussed. Firstly, half of the authors refer to Russia-Ukraine Conflict (47%) as the prominent example of hybrid warfare. A closer look on the articles shows that often time Russia-Ukraine Conflict is the only example in many articles that the authors discussed in detail with a reference to hybrid warfare. Other examples are usually given as series of examples in the same text, but not as a major example that models the hybrid warfare concept. Furthermore, two other examples, “Russia’s recent activities against West or NATO”, are also closely related to the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. In short, these data verify the argument that “Russian-Ukraine Conflict is perceived by international community as a model for hybrid warfare.” The other important issue that is implied in the results is the variety of the examples. Examples are so distinct in their types that they range from “ISIL’s Warfare in Syria” to the “Soviet invasion of Afghanistan”. This is another indication of the broadness and ambiguity of the concept.

Lastly, there are 9 articles (14%) that attributes the hybrid warfare concept to Gerasimov Doctrine, which is not a correct way of explaining the origins of the concept as mentioned in the first part of the paper. This is an important ratio- although not as high as we expected- that denotes the insufficient knowledge of the authors.

4. Conclusion

As Hew Strachan noted, “Words convey concepts: if they are not defined, the thinking about them cannot be clear… Such ambiguity creates confusion within individual nations, let alone alliances ostensibly speaking a common language” (Strachan, 2013) Indeed, as words convey concepts, concepts shape our defence understanding, and thus our armed forces, doctrines and the way that armed forces fight. Recently, as one of the most widely used terms in defense community as well as in the core documents of the EU and NATO, hybrid warfare is the leading concept to shape our defense understanding. However, hybrid warfare is a concept as controversial as it is popular. Frequently criticized for being ambiguous and weak as a concept, it carries the risk of misleading the defence community and obscuring the sound strategic thought.

This study demonstrated that hybrid warfare is an ambiguous term. According to the results of the content analysis conducted in this paper, 70% of the time, authors imply different concepts even though they used the term hybrid warfare. Under these circumstances, it requires to be too optimistic for a sound discussion in the defense community, where people cannot speak the same language. It is understandable, even commendable, that analysts endeavour to grasp and conceptualize contemporary warfare. However, the opportunity cost of misconception is too high, as it creates confusion rather than clarity. Considering the increasing number of terms to describe warfare in the last three decades, we believe, it is high time that international defence community built consensus over the actual meaning of hybrid warfare.

Bibliography

Bartles, C. (2016). Getting Gerasimov Right. Military Review, (January-February), 30–38.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods (4th Editio). New York: Oxford University Press.

Complex crises call for adaptable and durable capabilities. (2015). Military Balance, 115(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2015.996334

Gerasimov, V. (2013). The Value of Science in Anticipation. Military Industrial Courier, 8(476). Retrieved from http://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632

Gray, C. S. (2012). Categorical Confusion? The Strategic Implications of Recognizing Challenges Either As Irregular or Traditional. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College.

Hoffman, F. G. (2007). Conflict in the 21 st Century : The Rise of Hybrid Wars. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from http://www.potomacinstitute.org/

Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities. Reading: MA: Addison-Wesley.

Irregular Warfare (IW) Joint Operating Concept (JOC). (2007). Assessment (Vol. Version 1.). Department of Defense. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.130.6501&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Joint Publication 1-02 Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. (2001). Department of Defense DOD.

Joint Publication 3-13, Information Operations. (2014).

Joint Special Operations University Library. (2018).

Kofman, B. M., & Rojansky, M. (2015). A Closer look at Russia ’ s “ Hybrid War ”. Kennan Cable.

Lindley-French, J., Cornish, P., & Rathmell, A. (2010). Operationalizing the Comprehensive Approach. London.

Maas, J. (2017). Hybrid Threat and CSDP. In J. Rehrl (Ed.), Handbook on CSDP- The Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union (pp. 125–130). Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports of the Republic of Austria. https://doi.org/10.2855/764888

Michta, A. (2015). Judy Asks: Will Hybrid Warfare Defeat Europe?

NATO Topics: A ‘“comprehensive approach”’ to crises. (2018).

NATO Transformation Seminar. (2015). In White Paper- Next Steps in NATO’S Transformation: To the Warsaw Summit and Beyond. Washington.

Nicoll, A. (2015). Judy Asks: Will Hybrid Warfare Defeat Europe?

Nolan, P. (2017). How Putin Uses Fake News to Wage War on Ukraine.

Pindják, P. (2014). Deterring hybrid warfare: a chance for NATO and the EU to work together?

Poli, F. (2010). An Asymmetrical Symmetry: How Convention Has Become Innovative Military Thought. U.S. Army War College.

Porche III, I. R., Paul, C., York, M., Serena, C. C., Sollinger, J. M., Axelband, E., … Held, B. J. (2013). Redefining Information Warfare Boundaries for an Army in a Wireless World. RAND Corporation.

Puyvelde, D. Van. (2015). Hybrid war – does it even exist? NATO Review Magazine, 2015–2017. Retrieved from http://www.nato.int/docu/Review/2015/Also-in-2015/hybrid-modern-future-warfare-russia-ukraine/EN/index.htm

Renz, B. (2016). Russia and ‘hybrid warfare’. Contemporary Politics, 22(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201316

Renz, B., & Smith, H. (2016). Russia and hybrid warfare – Going beyond the label. Aleksanteri Papers. Retrieved from www.helsinki.fi/aleksanteri/english/publications/aleksanteri_papers.html

Robinson, L., Helmus, T. C., Cohen, R. S., Nader, A., Radin, A., Magnuson, M., & Migacheva, K. (2018). Modern Political Warfare: Current Practices and Possible Responses. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1772

Seppälä, T. (2002). “New wars“ and old strategies: From traditional propaganda to information warfare and psychological operations. In 23 Conference and General Assembly IAMCR/AIECS/AIERI International Association for Media and Communication Research, Barcelona,. Barcelona.

Snegovaya, M. (2015). Putin’s information warfare in Ukraine: Soviet origins of Russia’s hybrid warfare.

Strachan, H. (2013). The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, P. M. (1995). Munitions of the Mind. A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present era. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

UK House of Commons Defence Committee. (2010). The Comprehensive Approach: the point of war is not just to win but to make a better peace. HC 224, Seventh Report of Session 2009–10.

*Non-resident Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon, PhD Student in Université de Catholique Louvain ↑

**Master student in international security and defence at Institut Libre d’Etude des Relations Internationales (ILERI) ↑