ABSTRACT

Flanders has been increasingly receiving highly educated asylum seekers and refugees (HER) for the last decade. It is interesting that native-migrant employment gap is higher for highly educated refugees than for lower educated refugees in Flanders. As a part of the ESF project “All-in-one 4HER”, this research aimed to explore the underlying reasons for this fact and define the challenges faced by highly educated refugees during their integration process in the labour market. Having analysed the mixed methods data collected, three groups of key findings are explained. While the most important challenge is assessed as the language barrier, it has been found that lack of guidance and information for their education level is another factor lengthening their integration process. Difficulties in transforming their skills and qualifications into the local labour market is also instrumental in lengthening this period. As a solution, a considerable number of them follow examples around them and select shorter, more guaranteed career paths to mostly bottleneck jobs deviating from their previous studies and experiences.

Keywords: Migration · Refugee · Integration · Labour Market · Flanders · Employment · Mentoring

Fatih Yilmaz, Director of Partnerships and Projects at Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Dr. Fatih Aktaş, Research Assistant at Beyond the Horizon ISSG

1. INTRODUCTION

The arrival of asylum seekers in the EU countries has increased over the last decade and Flanders is one of the regions that has been a destination for highly educated refugees. One of the most noticeable and distinctive features of the refugees/asylum seekers who immigrated to Flanders after 2016 is that a remarkable number of them are highly educated, can speak at least one foreign language, and had a professional career in their home countries. Experiences in their countries such as human rights violations, hunger, violence, racism, suppressing their prospects, etc. force them to leave their home countries. These refugees have mostly positive perceptions of the human rights situation and democracy in Europe, and give even more weight to these than to the economic opportunities Europe has to offer (Timmerman, Clycq, Levrau, Van Praag & Vanheule 2018, 18). Although those with better qualifications but have minimal prospects in their home countries are assumed to be much more willing and ready to integrate to a new environment, the integration process can really be difficult for many of them.

This article reflects the research carried out at the initial phase of All-in-one 4 HER project “Fast-track integration of highly educated refugees into the labour market”. The societal challenge addressed by the project is the employment gap between immigrants and natives in Flanders, Belgium. This project aimed to develop a model for a faster and better labour market integration process of refugees through informing and connecting. The model developed by the project is presented in the “Handbook for integration supporters” (De Winter, Van den Berckt, Yilmaz 2021).

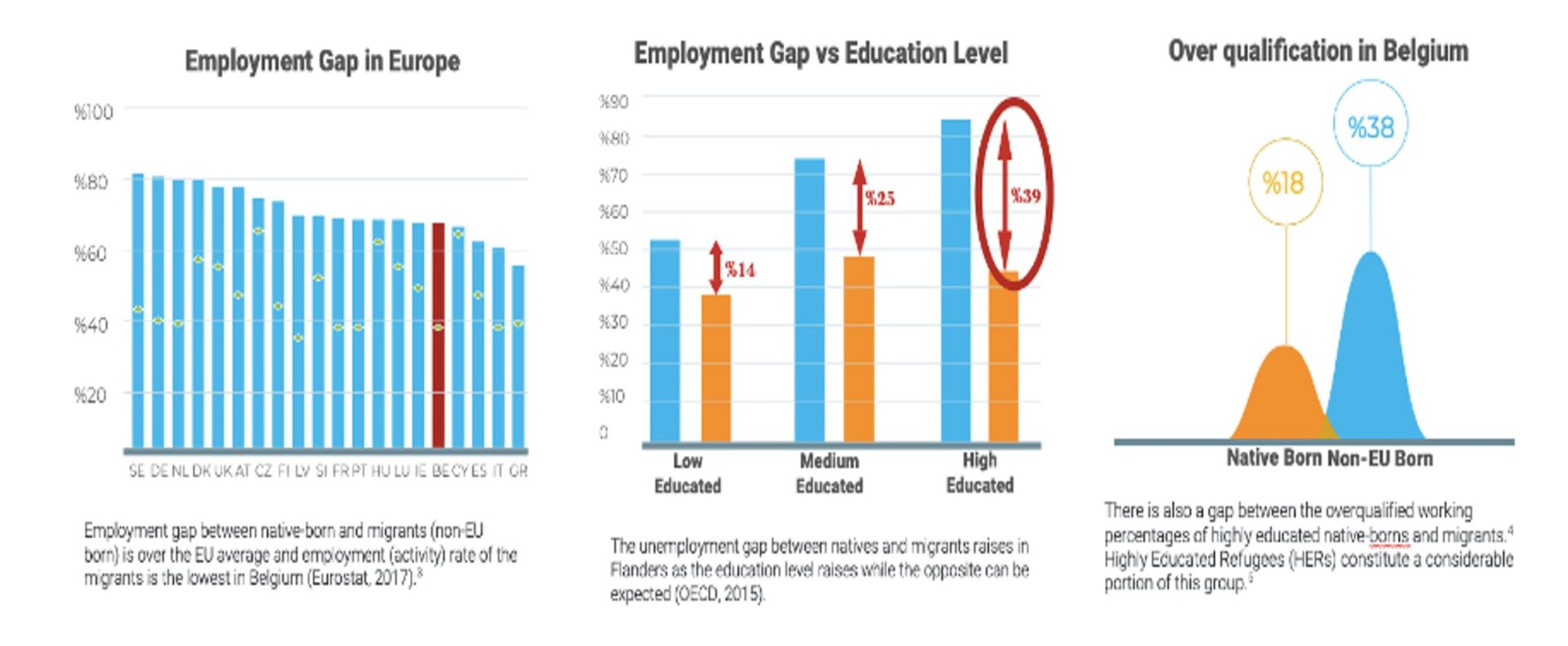

Despite having a developed labour market integration policy and available funding, the immigrant–native employment gap in Belgium is one of the largest in the EU (Eurostat, 2017). It is interesting that this gap is increasing by the level of education, while one would normally expect the opposite (OECD, 2015). Furthermore, overqualified working rates of migrants (non-EU citizens) is also far higher than Belgian natives (FOD, 2018) (See figures 1-3). While vacancy rates in Belgium are among the highest in the EU, migrants are yet to be seen as talents who can fill in the labour gaps. Although highly educated refugees constitute a considerable portion of migrants (OECD, 2019), the EU doesn’t have a specific integration policy addressing this target group yet. However, there have been some individual and local initiatives in some countries including Flanders (Kennisrotonde, 2016 & European Parliament, 2016).

Figures 1-2-3. Employment gap statistics**

Increasing number of highly educated refugees can lead to rethinking the existing ideas regarding ideal integration processes and how they lead to particular outcomes (Timmerman et al., 2018). There are few studies specifically focusing on integration of Highly Educated Refugees (HER) in the labour market, exploring the reasons behind the employment gap and recommending solutions in Flanders. Based on a quick scan of recent studies and projects on labour market integration of refugees, several major findings can be considered and/or validated for highly educated refugees in Flanders. In the recent literature, it can be seen that emphasis is placed on finding a job at an appropriate level, the length of the integration period, language learning, recognition of qualifications, and gender related differences.

Working at level is one of the indicators of immigrants’ labour market integration. Refugees are much more likely to be overqualified than other migrants in Europe (European Commission, 2016). Representation of immigrants at different level jobs can be a complimentary indicator. In the Flemish Labour market, ‘’compared to natives, immigrants are under-represented in public sector and white-collar private sector jobs, and are over-represented in the less well-paid blue-collar jobs and temporary employment” (Pina, Corluy, Verbist 2015). It was found in Finland that one of the most important goals in the lives of well-educated refugees was to find a job according to their own education level, but this can be extremely difficult (Yija¨la¨ and Luoma, 2019).

Concerning the length of the integration process, it takes refugees up to 20 years on average to have a similar employment rate as the native-born (European Commission, 2016). In the first 5 years after arrival, only one in four refugees is employed, which is the lowest of all migrant groups (European Commission, 2016). This number includes highly educated refugees as well. The length of this process is mostly associated with language barriers, difficulties in transmitting qualifications, and a lack of local experience. In addition to this, existence of ‘refugee entry effect’ is another factor explained by Baker, Dagevors and Engberssen (2017). Compared to labour and family migrants, refugees often arrive in their destination country less prepared and suffering from traumatic experiences. Moreover, they need to apply for asylum and await the decision on their residency status. A number of success factors for integration policy have been drawn up on the basis of two overview studies (European Parliament, 2016 and Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016). However, these are not specific to higher educated people. The main factors are providing good qualification of experience and training, quick start of language learning tailored to the person, creation of individual integration plans, and building work experience (Kennisrotonde, 2016).

Language barriers are one of the mostly mentioned obstacles for integration of HERs. The employment rate of refugees increases as their language skills improve. This counts for the refugees who have to learn the host-country language, and don’t have prior knowledge of it. Knowledge of English as a common international language can be helpful to accelerate their integration process. However, there is evidence that refugees with the knowledge of local language, especially those from the northern part of Africa having French as their mother tongue, are still disadvantaged on the labour market and face major obstacles both to finding a job and to keeping it. Those obstacles seem to have little to do with their individual characteristics or skills (especially their language skills or their education). Rather, non-observable external factors, including cultural barriers and discrimination, seem to play a major role (European Commission, 2016).

Difficulties in recognition and transmission of qualifications is also instrumental in late integration. Unlike their EU-born peers, for refugees “There is an absence of returns on higher education in terms of labour market integration. More specifically, education beyond a secondary degree does not yield any additional […] returns.’’ (Peschner, 2017). It is generally assumed that there is a positive effect of education in one’s home country on the probability of participation in the labour market. But the characteristics of a bachelor’s education in the labour market are not currently specified and it matters very much whether an immigrant’s education has been acquired in the origin country before migration or in the destination country (Philip, Mark and Lisa 2021). On the other hand, it is also important to consider the fact that, for refugees, ‘’vocational capabilities are directly transmissible, whereas general academic skills are not’’ (Yija¨la¨ and Luoma, 2019).

Gender based differences in integration is another field that the literature focuses on. In general terms, “bringing refugee women into employment is a particular challenge.’’ (European Commission, 2016). This can result from “a different household composition, with widespread female inactivity and more children’’ (Pina, Corluy, Verbist 2015) and cultural differences. Whether this applies to highly educated women refugees is a gap that still needs to be explored.

As a result of our literature review, it can be said that although there is quite a wide range of literature on immigrants’ integration in the labour market, specific labour market integration challenges of highly educated refugees in Flanders are yet to be researched more in depth. There was a need for such research before setting up a solution in the All-in-one 4HER project to properly define the societal challenge, in order to develop a model for a faster and better integration process.

To reach this end, a small-scale research was conducted to understand the challenge more deeply in the Flemish context. This research aims to define the underlying reasons for a longer integration period of highly educated refugees into the labour market and define the main challenges they face towards labour market integration.

2. METHODOLOGY

A mixed data collection method was used in this research. Mixed data collection was carried out through a survey (quantitative) and interviews (qualitative). Despite the fact that the data gathered by quantitative method is considered rigorous, reliable and persuasive, it does not allow the researcher(s) to explore the feelings and to observe the body-language of the subjects in depth since the contact with the subject is limited. The attitudes and feelings on ‘integration’ have both objective and subjective manifestations. Therefore, a mixed data gathering method was carried out through face-to-face, in-depth interviews with some of the subjects selected amongst the sample. This helped capture subjective manifestations, and supported and enriched the data gathered through the quantitative method.

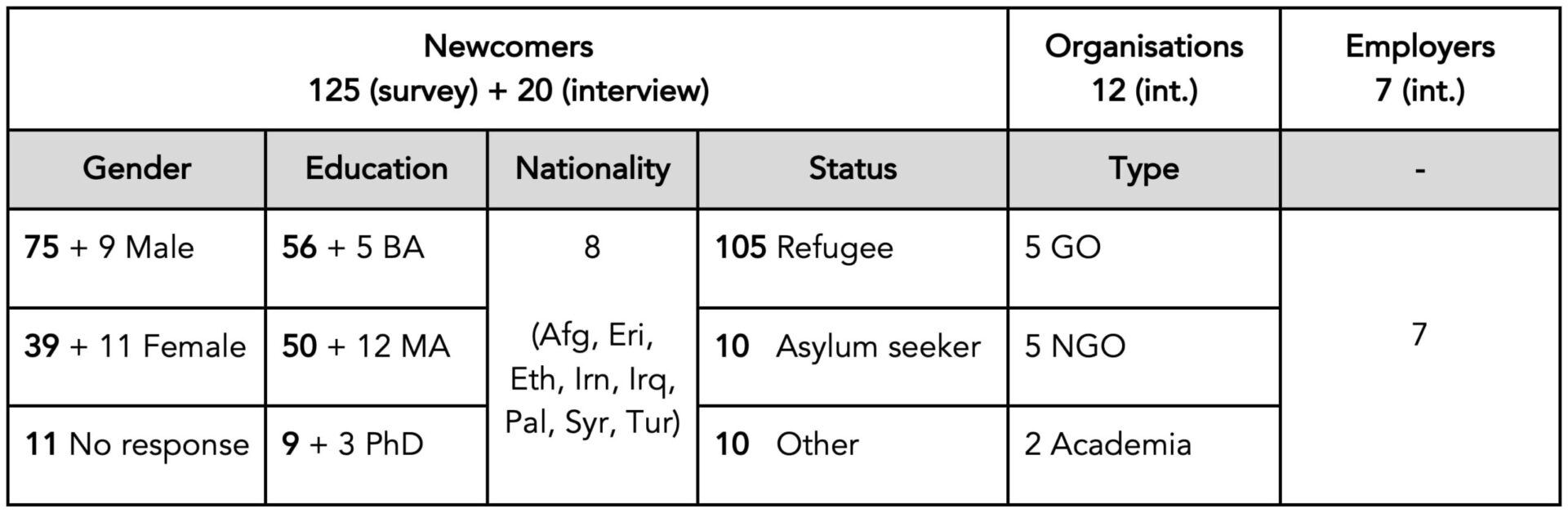

As a part of the All-in-one 4HER Project, a small scale pre-structured online survey was conducted with the participation of 125 highly educated refugee adults (including asylum seekers) across Flanders, Belgium between May – December 2019 by Beyond the Horizon ISSG. The eligibility criterion used in the project was very strict: only newly arrived (within the last 5 years), high-educated refugees were allowed to participate. These HERs came from 8 different nationalities (Afghan, Eritrean, Ethiopian, Iranian, Iraqi, Palestinian, Syrian, and Turkish). A gender balance was sought among the participants. Nearly half of the participants had a bachelor’s degree, and the rest had master’s or PhD’s. This survey was supplemented with in-depth interviews which were conducted with 7 employers, 12 public sector organisation (GO, NGO) employees and 20 highly educated refugees. The participants were asked to reply to a dozen questions on their attitudes and experiences about integration of HERs into the Flemish labour market. The details of the participants are depicted in figure 4.

Figure 4. Survey and interview participants

3. RESULTS AND KEY FINDINGS

After the analysis of the quantitative survey data and supporting in-depth qualitative interview data, key findings were identified about highly educated newcomers’ attitudes toward the process of integration as well as organisations’ and employers’ role in this process. This section provides an overview and summary of these key analytical findings in three groups with some meaningful illustrations of the survey data.

Language

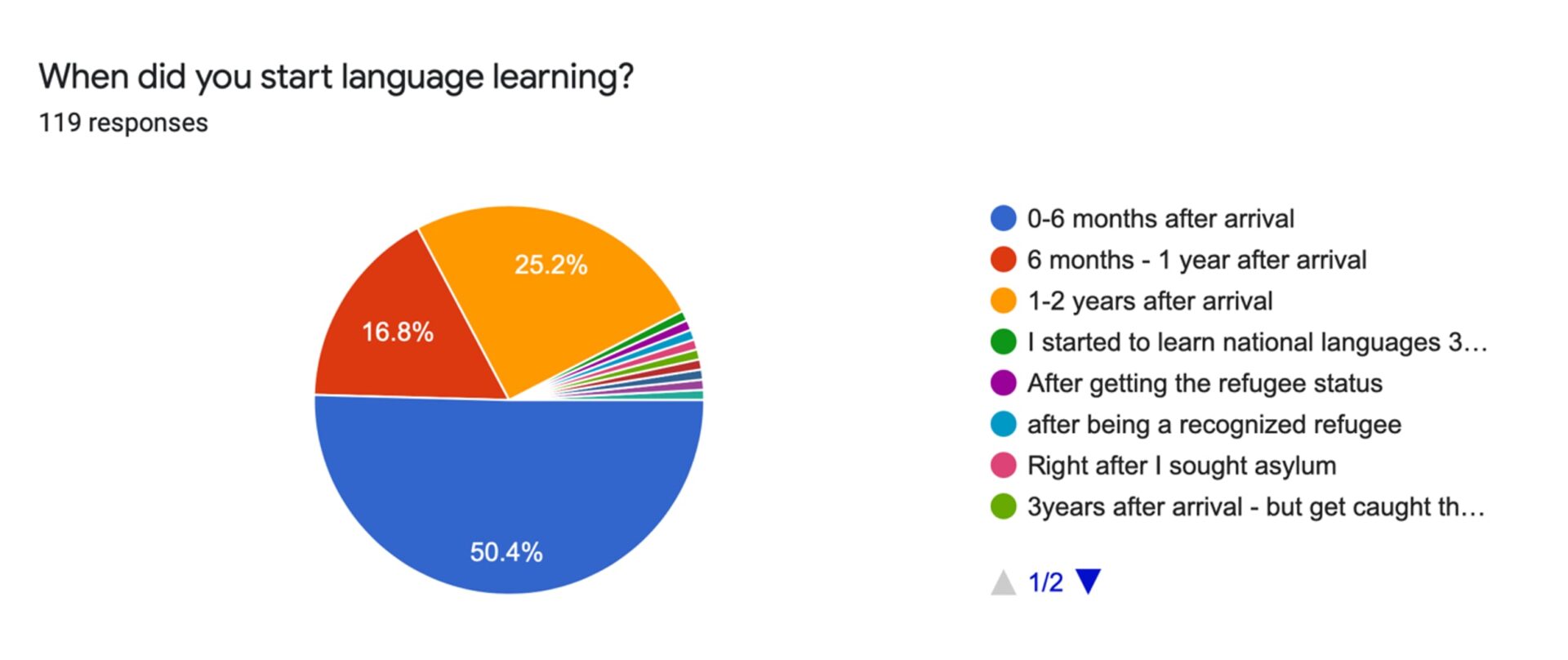

Firstly, motivation and awareness of learning the local language is viewed as high despite the hard circumstances. A big portion of the participants connect the learning of a new language with a number of positive words and phrases in the interviews and are aware of the importance of learning the local language. As we see in the graphic as an indicator of motivation, 50.4 percent of the participants started learning the local language within the first six months of their arrival. In the first year, this rate is totally around 70 percent. However, 25 percent of the participants started learning the local language within 1-2 years. The obligation of following a language for receiving financial support from social services also played a role in their motivation. While speaking English can demotivate some newcomers to start learning the local language, some regret starting late because of difficulties experienced in finding a job. On the other hand, the (perception of) need for attaining financial means as soon as possible can also hinder their language learning or result in postponing to later stages.

Figure 5. Starting language learning

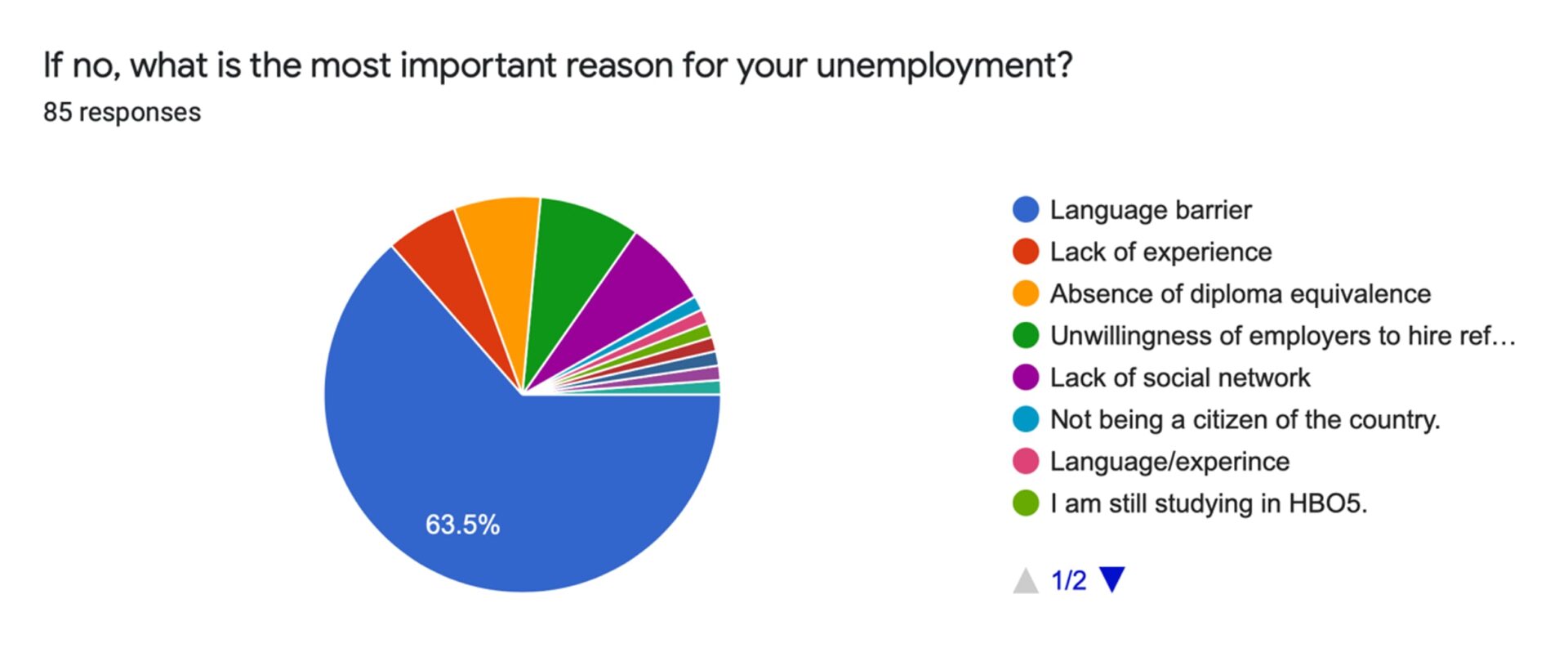

Secondly, the local language barrier was viewed as the most significant issue in terms of integration into the Flemish Labour Market. Not being able to speak the local language is, even after being officially recognized, a never-ending drawback for refugees. They encounter this problem in every aspect of their life which can cause strong feelings of discrimination and isolation from the society. Moreover, the information about this issue gathered from the interviews is also supported by the survey results. Among the participants, 66% viewed the language barrier as the foremost obstacle in finding a job that matches up with their level of education. The additional obstacles to finding a job are seen as discrimination, lack of experience, lack of diploma equivalence, and lack of social network by the participants.

Additionally, most of the participants speak more than one language. Despite the fact that they learn local languages (French and/or Dutch) at a considerably good level, they are compelled to continuously improve their language since employers demand a nearly perfect level.

Figure 6. Most important reasons for unemployment

Thirdly, learning the local language is not an urgent issue for a considerable portion of participants who speak English. The survey results show that the participants with a good level of English do not perceive the significance of learning the local language and do not feel a need to take immediate action upon their arrival to learn and use it in their daily life. Lack of feeling urgency about learning the local language is demonstrated by 31 out of the 125 participants. The figures indicate that 38.75 percent of the participants who can speak English have the same or lower local language level than non-English speaking participants. During the interviews, it became apparent that English speaking refugees postponed learning the local language and tried to find English speaking jobs first. There are a number of HERs who found jobs with only English, however this is rare when compared to all.

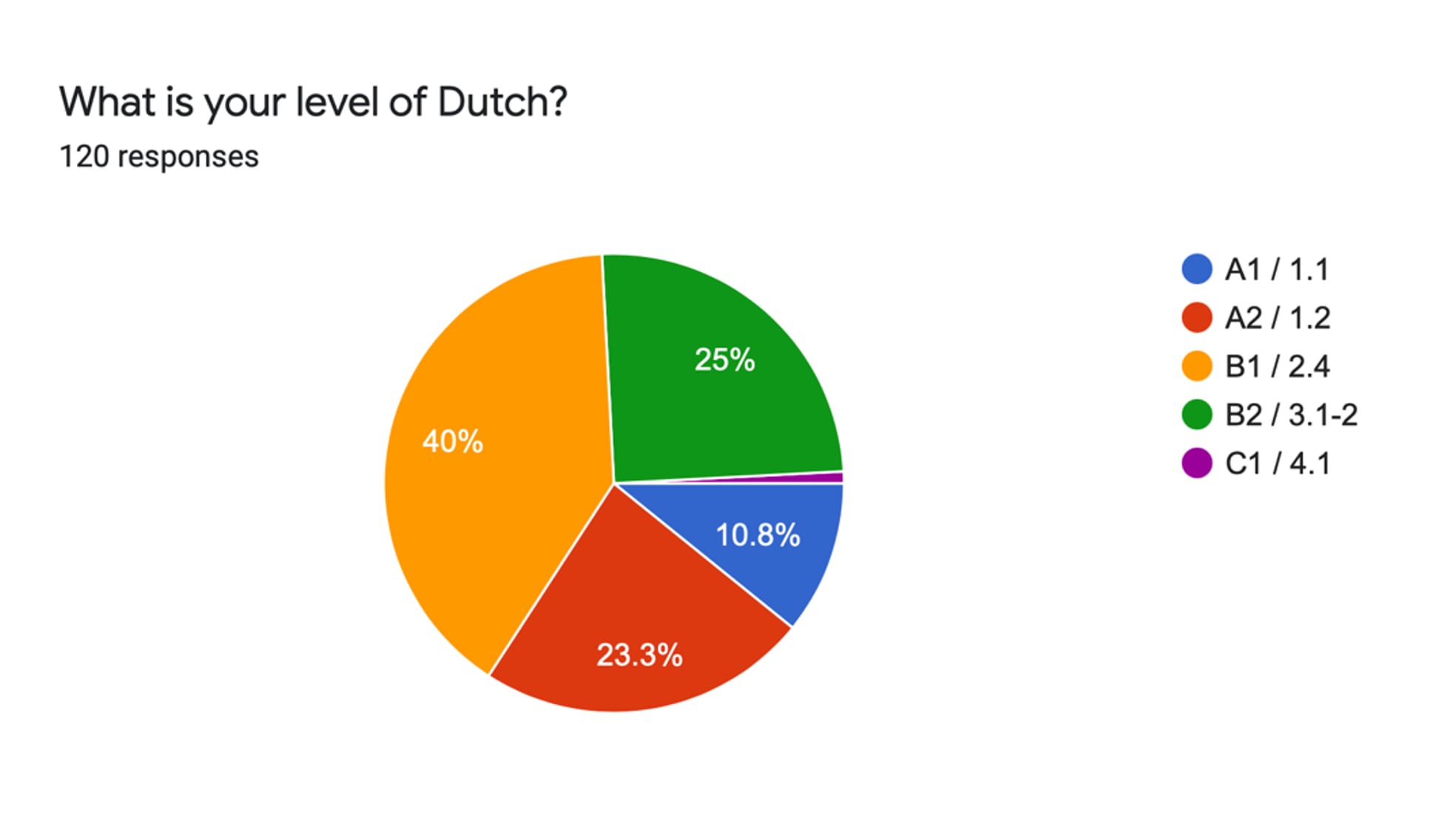

Figure 7. Level of local language

Moreover, gender affects the learning language process and integration into the Flemish Labour Market. According to the survey results, female participants started to learn and improve on the local language later than men. Specific reasons for female HER’s later language learning and later integration are related to house care and babysitting. Babysitting was seen as one of the most important obstacles in terms of learning local language in interviews. Beyond the babysitting consuming most of the mother’s daily time, it also restricted the mother’s socialisation. Additionally, traumatic experiences before their arrival may also play a role in being late to start taking active steps to learn the language and integrate into the labour market.

Lack of Information and Guidance

Another problem is indecisiveness and guidance. Indecisiveness led by lack of information and guidance plays an important role in delayed integration into the labour market. The survey and interviews determined that lack of information about the labour market and a lack of guidance made career decisions difficult for HERs. Most of the interviewees said that they couldn’t find information in a known language and they didn’t know where to look for information. Those staying in reception centres after their arrival also said that they had limited access to the internet.

Most of the participants think that they didn’t get enough guidance at their education level, which led to difficult decision making and time wasted. A considerable portion of the participants got information from their friends rather than professionals. 19.5 percent of the participants state that they have heard from their friends that there is a language course for newcomers. Moreover, 43.7 percent of the participants stated that they learned about diploma equivalency from their friends. 43.1 percent of the participants answered the question “Have you heard, been invited to or informed about various activities guiding refugees for finding a job in Flanders?“, as “I have not heard and not been invited.“ Furthermore, only 27.2 percent of respondents believe that government organisations can guide them in finding jobs at their level. 67.5 percent of participants state that they do not have enough guidance according to their education level. The interviews highlighted that the lack of guidance and information may lead HERs to follow the examples around them. While good examples can make nice role models for HERs, bad examples may cause wrong decisions, time wasted and increased frustration.

Transfer of qualifications and skills to the Labour Market

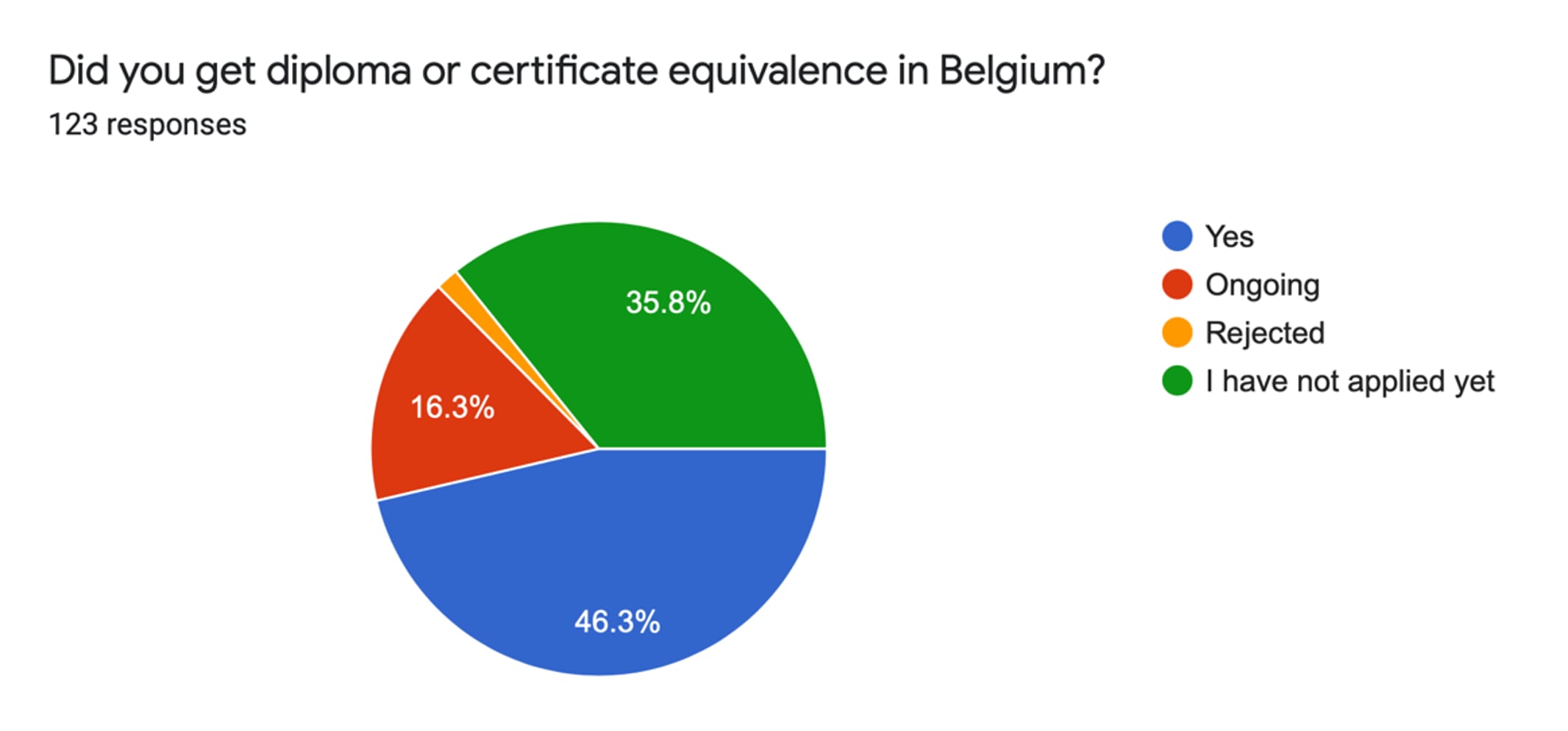

On the other hand, a considerable portion of HERs possess little awareness of diploma equivalence and how to use their qualifications in the labour market. Although 46.3 percent of participants had been granted diploma equivalence and 16 percent of participants were in their diploma equivalency process, 35.8 percent participants responded that they had not yet applied. 66 percent of those who answered this question believe that diploma equivalence is inessential. This was further investigated in interviews which showed that many HER’s don’t actually know why equivalence is necessary. Many did not know how to showcase their skills in the labour market of the host country.

Figure 8. Recognition of qualifications

A big portion of HERs had superficial knowledge about the Flemish labour market culture and a lack of knowledge on showcasing their competencies in the Flemish labour market. In terms of the number of applications for a job, HERs can generally be described as active. 39.1 percent applied to a range of 1-10 jobs, 26.4 percent applied to a range of 10-100 jobs, and 14.5 percent applied to a range of 100-200 jobs. But survey results show that 43.7 percent of job applicants did not receive any job interview invitations even though they applied to a lot of jobs. According to some interviewees, this was attributed to a lack of knowledge about the labour market. They didn’t know how to write a good CV in Flanders or how to behave and respond during interviews. They learned this through experience and asking more experienced friends, which took a long time for them.

It was seen in the interviews that a big portion of HERs did not have sufficient knowledge and experience in the Flemish labour market culture, about recruitment processes and job application procedures. There is a necessity for guidance on topics such as professional CV writing, attitudes and behaviours in job interviews.

Some working interviewees mentioned also that they had difficulties adapting to the working environment and culture, specifically concerning relations with their colleagues and supervisors.

Another perceived significant barrier to integration into the Flemish Labour Market: Discrimination According to the survey results, second most significant perceived barrier for finding a job among HERs is unwillingness of employers to hire; in other words, discrimination. Many HERs mentioned this during the interviews that they had faced discriminatory experiences during their training, internship and job application process. Some female participants think that “Muslim women wearing scarves are not welcomed positively“ by the Flemish employers. Furthermore, racial differences make it difficult for HERs to be accepted in the Flemish labour market.

Survey results show that 43.7 percent of job applicants did not receive any job interview invitations although they made many applications. This was supported during the interviews by several HERs. A university professor mentioned that he applied for more than a hundred jobs over a 5-year period without being invited to an interview once. He felt that it was because of his origin and name, which was incredibly frustrating and hurtful, and he ended up starting a low-level job. In line with this, 53 percent of employed survey respondents were working below their level of their education.

A recruiter of a big company said that there is still a considerable amount of unconscious bias against immigrants among the recruiters, although some preventive measures are being taken in big companies. On the other hand, several relatively small employers mentioned lack of knowledge about hiring refugees, the validity of their competencies and necessary paperwork, which led them to doubt whether to employ refugees.

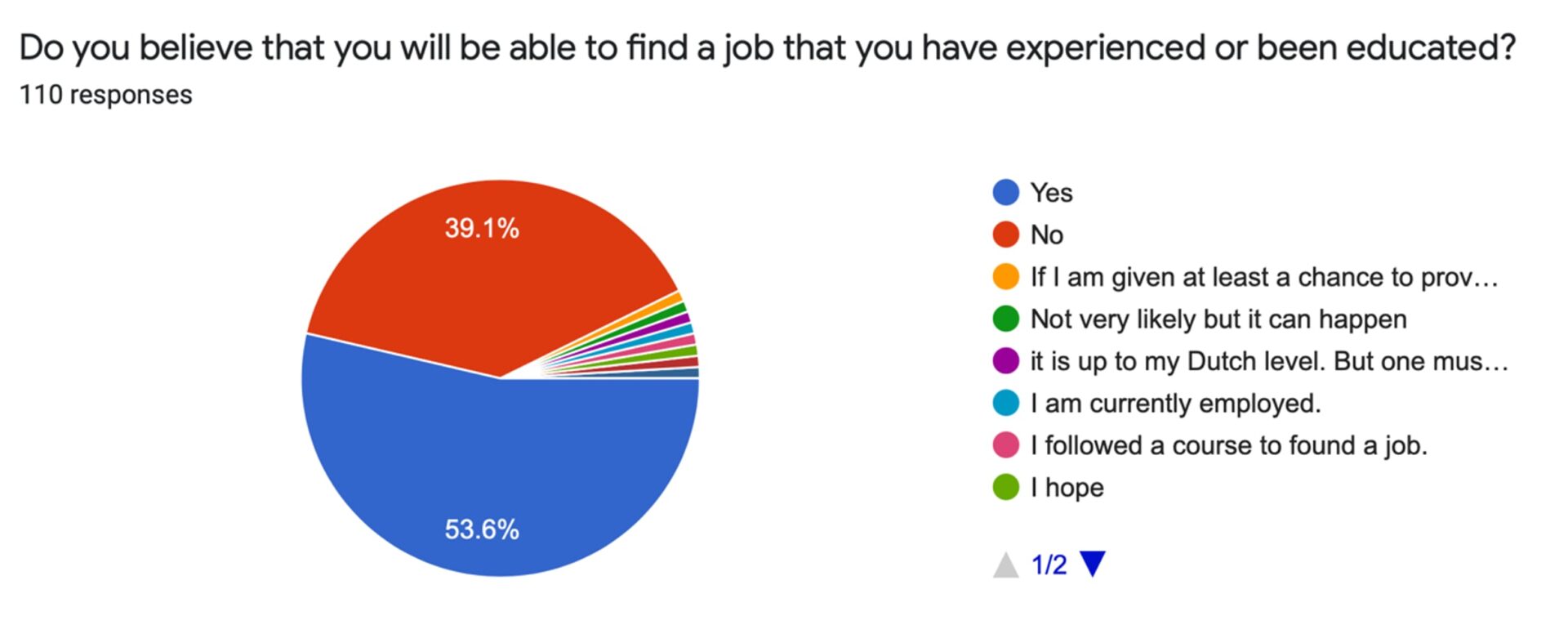

Lastly, a big portion of HERs don’t believe that they will be able to find a job in Flanders according to their background (study, experience). As a solution, many of them are focusing on bottleneck jobs (ICT, Nursery, etc). 39.1 percent of the survey respondents didn’t believe that they would be able to find a job for which they have experience and education in from their home country. In the interviews, some reflected their hopelessness because their academic or vocational skills were not transferable to the Flemish labour market, although they had very high positions in their home country such as professor, judge, pilot, doctor, etc. In line with this, many interviewees responded that being experienced and well-educated does not help in finding a job.

In this context, many HERs are searching for new career options and paths which are shorter, faster and have a stronger job guarantee. The bottleneck jobs help most of them at this point, and it is seen among the interviewees that the direction towards these jobs is gradually increasing. ICT jobs, nursery and accountancy are recently popular ones.

Figure 9. Expectation to find a job in line with education and experience

4. CONCLUSIONS

This article aimed to define the underlying reasons for a longer integration period of highly educated refugees into the labour market and to define the main challenges they face in Flanders, Belgium. The results and key findings of the research are mostly in line with the selected general findings from the literature review. These are validated specifically for Flanders in this research. There are also some interesting results reflecting the experiences and attitudes of refugees regarding their integration processes.

The findings of the research are grouped and explained in three parts. Initially, they face challenges concerning language. It is interesting to find out that highly educated refugees’ motivation and awareness of learning the local language is quite high despite the hard circumstances they are facing. Most of the refugees view the local language barrier as the most significant reason for their unemployment due to lack of communication and difficulties in accessing information and networks. On the other hand, it is not an urgent issue for a considerable portion of English-speaking participants who try to find jobs before learning the local language. Nevertheless, most HERs have significant difficulty in finding a job without learning the local language. It is also interesting that those who learn local languages at a considerably good level still feel compelled to improve their language since employers demand a nearly perfect level.

Most highly educated refugees felt that they had a lack of information and guidance tailored to their education level. Indecisiveness led by lack of information and guidance plays an important role in delaying integration into the labour market. They spent more time than expected trying to find a suitable path towards a job. The lack of guidance and information may lead HERs to simply follow the examples around them. While good examples can be strong role models for HERs, bad examples may cause wrong decisions, time wasted and increased frustration.

Lack of awareness and knowledge on transferring qualifications and skills to the Flemish labour market is another significant challenge. A considerable portion of HERs possessed little awareness of diploma equivalence and how to use their qualifications in the labour market. Also, a big portion of HERs had superficial knowledge about the Flemish labour market culture, which impacts their adaptation to the workplace after starting a job. Lack of information, discrimination and unconscious bias among employers are also significant factors that lengthen their integration process. A large portion of HERs don’t believe that they will be able to find a job in Flanders according to their background (study, experience). As a solution, many of them are focusing on bottleneck jobs which can have easier and shorter paths to employment.

From a gendered perspective, highly educated female refugees tended to have a longer period of language learning and integration than men because of several reasons including spending more time doing domestic labour, babysitting, and dealing with traumas from their previous life.

Although this article is based on small-scale research in Flanders, it makes a complementary contribution to the growing literature on labour market integration of immigrants based on their education level. This study can be carried out on a larger scale and adapted to other EU countries. Extending the research to include all immigrants is also possible. The findings of this research are likely to have considerable exterior validity due to many regions across the EU facing a similar influx of highly educated refugees. If the research can be repeated in the other EU countries, a logical comparison of outputs between countries can be made.

REFERENCES

Bakker, L., Dagevos, J. & Engbersen, G. (2017). Explaining the refugee gap: a longitudinal study on labour market participation of refugees in the Netherlands, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43:11, 1775 1791, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1251835

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2016). From refugees to workers, volume 1, Dusseldorf. Retrieved from https://www.bertelsmann- stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/from-refugees-to-workers-mapping-labour-market-integration-support-measures-for-asylum-seekers-and-2/

Dahlberg M., Egebark J., Vikman U., Gülay Ö. (2020). Labor Market Integration of Low-Educated Refugees: RCT Evidence from an Ambitious Integration Program in Sweden IFN Working Paper No. 1372

De Winter, H., Van den Berckt, I. & Yilmaz, F. (2021). Handboek voor integratie ondersteuners: Versnelde Integratie van Hoogopgeleide Vluchtelingen (HER) en Anderstaligen (HOA) op de Vlaamse Arbeidsmarkt. Retrieved from https://all-in-one4her.eu/pdfs/handbook-versnelde-integratie.pdf

European Commission (2016). How are refugees faring on the labour market in Europe? A first evaluation based on the 2014 EU Labour Force Survey ad hoc module, Working Paper 1, ISSN: 1977-4125

European Commission (2016). Challenges in the Labour Market Integration of Asylum Seekers and Refugees. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/?action=media.download&uuid=E1A48891-A0BF-53D4-6E1012442304F524

European Parliament (2016). Labour market integration of refugees: strategies and good practices, European Union, Brussels. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578956/IPOL_STU(2016)578956_EN.pdf

EUROSTAT (2017). Activity rates for the population aged 20-64, by place of birth. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Activity_rates_for_the_population_aged_20-64,_by_place_of_birth,_2016_(%25)_MI17.png

Helbling, M., & Kriesi, H. (2014). Why citizens prefer high- over low-skilled immigrants. Labor market competition, welfare state, and deservingness. European Sociological Review, 30(5), 595–614.

Hoge Raad voor de Werkgelegenheid (2018). Stand van zaken op de arbeidsmarkt in België en in de gewesten. Retrieved from https://werk.belgie.be/nl/publicaties/hoge-raad-voor-de-werkgelegenheid-verslag-2018?id=47812

Kaida, L., Hou, F. & Stick, M. (2020). The long-term economic integration of resettled refugees in Canada: a comparison of Privately Sponsored Refugees and Government-Assisted Refugees, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46:9, 1687-1708, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1623017

Kennisrotonde. (2016). Welke initiatieven zijn er in het buitenland voor onderwijs aan hogeropgeleide vluchtelingen die leiden tot werk op niveau (MBO/HBO/WO) en hoe effectief zijn deze initiatieven? (KR.38).

Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Mo, C. H. (2013). Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 391–410. doi:10.1111/ajps.12012

Michielsen, J., Wauters, J., De Cuyper, P. (2014). Hoogopgeleide anderstaligen met een migratieachtergrond op de arbeidsmarkt: enkele cijfers.

OECD (2019). “Over-qualification rates, by migrant background: Percentages of employed highly educated, 25- to 34-year-olds, around 2016”, in Settling In 2018: Indicators of Immigrant Integration, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307216-graph117-en

Peschner, J. (2017). Labour market performance of refugees in the EU, Working Paper 1/2017, European Union, 2017, p. 16-17

Pina, Á., V. Corluy and G. Verbist (2015), “Improving the Labour Market Integration of Immigrants in Belgium”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1195, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js4hmbt6v5h-en

Philipp, L. , Marc, P. , Lisa, S. (2021). Does the education level of refugees affect natives’ attitudes? European Economic Review, 134, 103710, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103710

Timmerman, C., Clycq, N., Levrau, F.. Van Praag, L. & Vanheule D. (2018). Migration and Integration in Flanders: Multi Disciplinary Perspectives, Leuven University Press.

Van Dooren, G., De Cuyper,P. (2015). Connect2Work – Leidraad voor het opzetten van een mentoringproject naar werk voor hooggeschoolde anderstalige nieuwkomers.

Vandermeerschen, H., De Cuyper, P. (2018). Mentoring naar werk voor personen van buitenlandse herkomst.

Vandermeerschen, H., De Cuyper, P., De Blander, R. & Groenez, S. (2017). Kritische succesfactoren in het activeringsbeleid naar mensen met een buitenlandse herkomst. Onderzoek in opdracht van de Vlaamse minister bevoegd voor Werk, in het kader van het VIONA-onderzoeksprogramma. Leuven: HIVA – KU Leuven.

Yijälä, A., & Luoma, T. (2019). The Importance of Employment in the Acculturation Process of Well-Educated Iraqis in Finland: A Qualitative Follow-up Study, Refugee Survey Quarterly, Volume 38, Issue 3, Pages 314–340, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdz009

* This research is financed by European Social Funds (ESF) and Flemish Government under ESF Vlaanderen Transnationalitetit IV programme in the name of the “All-in-one 4 HER” project. For more information about the project please visit https://all-in-one4her.eu

˚ A shorter Dutch version of this research is published as a Chapter of the handbook “Handboek voor integratie ondersteuners”. See the handbook at https://all-in-one4her.eu/pdfs/handbook-versnelde-integratie.pdf

** Illustrations are available on the project website. Check “Challenges” for details at https://all-in-one4her.eu/aboutus.php