1. Introduction:

Maritime transport is crucial to the world’s economy as over 90% of the world’s trade is carried by sea, and it is the most cost-effective way to move goods and raw materials around the world at this time. The massive commercial maritime traffic makes more sensitive anchorage grounds, ports and maritime routes especially through narrow waters and congested chokepoints. Thereby, it increases the importance of maritime security which is the subject of serious concern to states, international organizations and other stakeholders in the maritime domain. On the other hand, the maritime threat environment is dynamic, and the risks will not remain constant. Operating in the oceans requires thorough planning and application of all available information. So, the security of maritime trade needs considerable intention.

Regrettably, some specific waterways have in recent times emerged as some of the world’s most dangerous routes for vessels and their crew members regarding pirate attacks. Piracy is one of the contemporary challenges of the maritime industry. This phenomenon has a global impact on maritime trade and security, especially during the last decades, when the activities of pirates increased exponentially in Southeast Asian and West African (Gulf of Guinea) in addition to East African (Somalia) coasts. However, there was a relative fall in 2017 compared to the previous years.

2. The Assessment of Piracy Incidents in 2017:

According to the 2017 Annual IMB (International Maritime Bureau) Piracy Report;

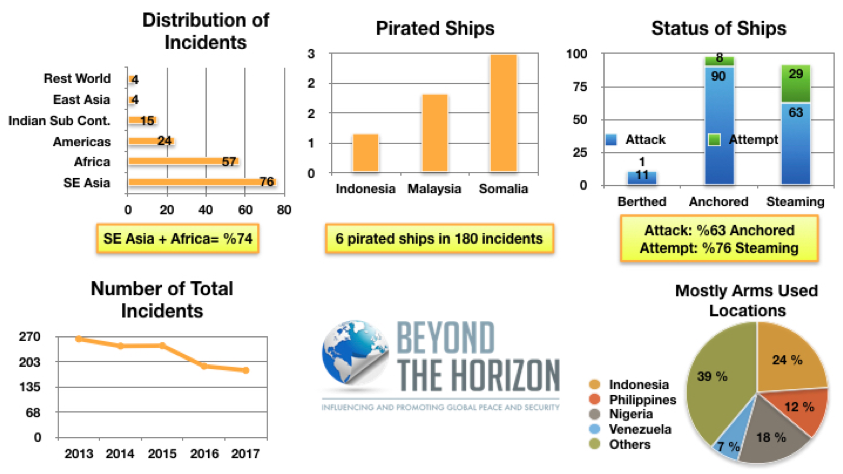

– 74% of total incidents were in Africa and Southeast Asia.

– Only 6 ships were pirated out of 180 incidents.

– 63% of the actual attacks were on anchored ships, and 76% of the attempts were on underway ships.

Figure-1 Assessment of Piracy Incidents in 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

– During the last 5 years (2013-2017), there was a steady decrease in the number of events, from 264 to 180.

– 3 crews (2 in Philippines and 1 in Yemen) were killed in the incidents.

– Locations, where arms (guns, knives and other weapons) were used most, were Indonesia, Philippines, Nigeria, and Venezuela.

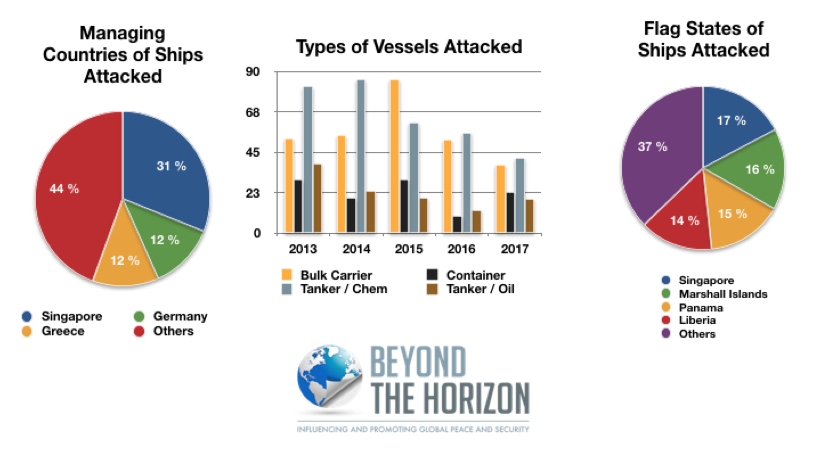

Figure-2 Assessment of Piracy Incidents as of ships & countries in 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

– The pirates mostly targeted tankers carrying chemical products, bulk carriers, and containers and tankers carrying crude oil.

– According to flag states; Singapore, Marshall Islands, Panama, and Liberia were targeted by pirates because Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands are the world’s three largest registries of deadweight tonnage (DWT).

– In this regard, the managing countries of Singapore, Germany, and Greece, which are the primary seafaring nations, were also susceptible to pirates.

As a result:

– Numerousness of criminals in Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia and Philippines,

– In addition to numerousness of criminals, the lack of state capacity and the presence of terrorist groups along the Nigeria coasts lies on the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean,

– Likewise, smuggling, drug trafficking, and violent robbery incidents along the coasts of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela in South America,

– In addition to all these reasons mentioned above, the intrastate and interstate conflicts in

Somalia in east Africa, piracy represents a serious and sustained threat to maritime security.

Figure-3 Assessment of Piracy Incidents as of Locations in 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

When we consider pirate attempts and attacks on commercial ships in 2017, 7 countries were in the spotlight out of 180 reported incidents.

– Indonesia, with 43 incidents, is in the first place as the country where most of the cases happened, although there is a significant decrease and only one ship was pirated. Positive actions of the Indonesian Authorities resulted in fewer incidents, but it is also believed that many attempts/attacks may have gone unreported. In this area, pirates are generally armed with guns/knives and normally attack vessels at anchor or in narrow water during the night.

– Indonesia is followed by Nigeria with 33 incidents. Unfortunately, we can’t say there is a decrease for Nigeria and pirates in this area are often well armed and more violent. They may also kidnap and injure the crews. All waters in/off Nigeria are risky, and even up to 170 nautical miles from the coast, attacks have been reported.

– Pirates/militants were active in the Philippines which had 22 incidents, a significant increase compared to the previous years. But, the good development in the Philippines has been that the kidnappings by militants have stopped recently because of the ongoing efforts of the Philippines military.

– 12 incidents in Venezuela and 11 incidents in Bangladesh occurred. There was a sharp increase in Venezuela. Puerto Cruz and Puerto Jose are more risky areas in Venezuela. In Bangladesh, the ships preparing to anchor were targeted. Additionally, attacks in Bangladesh have increased from 3 to 11 compared to the attacks in 2016. However, there is a significant decrease from 21 to 11 compared to attacks in 2014 due to the efforts of Bangladeshi authorities.

In addition to the 5 previously mentioned countries, Somalia and Malaysia attracted attention with 3 and 2 pirated ships, respectively. Although there were only 9 total incidents in Somalia, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, 3 of them resulted in a successful attack by pirates. This shows that the pirates in Somalia still possess the capability and capacity to carry out attacks and also indicates that they have gained experience with choosing targets.

3. Piracy in Somalia, Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean:

Since the beginning of the civil war in Somalia in 1991, the country has been controlled by rebel and clan-based groups and has little or no infrastructure. It has resulted in a fail-state and is one of the poorest and most violent countries in the world. There is no functioning government, no police or military infrastructure anywhere in the country. At the same time, Somalia is a country which has the longest coast in Africa.

On the second phase of the Somali Civil War in 2000, foreign fisherman exploited illegally rich fishing grounds because of the absence of an effective national coast guard on the Somalia coasts. They reduce the local fishing stocks which were the single source of income in Somalia. Local communities tried to respond by forming armed groups to deter invaders. These developments in Somalia have given rise to significant pirate activities, especially in the Gulf of Aden. The pirates have used the same tactics: skiffs to attack ships and utilization of small arms, RPGs, and rigid boarding ladders. The pirates approach the ships by skiffs powered by extra motors which make them faster than most of the commercial ships. The skiffs are small, and they can operate hundreds of nautical miles off the coast by using large mother ships from which they launch their attacks.

Pirates then take control of the ship and force the crew to move the vessel to anchor off the coast of Somalia. Then, they open the negotiation for payment of the ransom to release the crew and the ship. The pirates can also use the pirated ship as a mother ship.

In 2017, almost all attempts in the Somalia region were conducted by firing upon the ships, and 3 of the attacks resulted in hijacking; so, there were 3 successful attacks in the Somalia region. Almost all the attacks and attempts were conducted while the ships were underway. There were no crew members killed in the Somalia region, but most of the incidents resulted in the crews being taken as a hostage.

a. Counter-Piracy Measures in Somalia:

(1) Operations:

There were 3 different Combined Task Forces (CTFs), NATO, EU and CMF (Combined Maritime Forces) in the area until NATO formally ended its Operation Ocean Shield (CTF 508) in the waters off the coast of Somalia on December 15, 2016. Participating naval forces rely on long-range military reconnaissance aircraft to locate a pirate skiff that is just a tiny dot within hundreds of thousands of square miles of open Ocean. Once discovered, the aircraft relays the position of the skiff to the nearest warship which then proceeds at maximum speed to the suspected pirate’s location. The most cost-effective solution would be to stop the pirates at the coast, keeping them on the coast/territorial waters as to not to let them get lost in the expanse of the open ocean. The international naval forces also patrol these waters to understand the usual patterns of ships, which will allow them to identify and deter any suspected piracy event more easily. So, all entities involved carry out operations by coordinating with one another.

(a) Operation Ocean Shield (OOS) by NATO (NATO OOS, 2016):

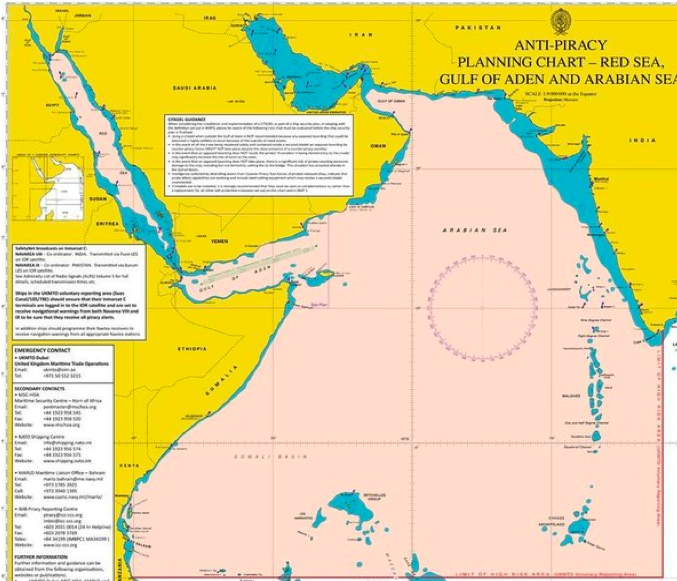

Figure-4 NATO Area of Operation for Counter-Piracy (NATO OOS, 2016)

OOS (by CTF 508) was NATO’s counter-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa. NATO helped to deter and disrupt pirate attacks while protecting vessels and increasing the general security in the region from 2008 until 2016. NATO’s role was to provide naval escorts and deterrence while increasing cooperation with other counter-piracy operations in the area to optimize efforts and tackle the evolving pirate trends and tactics. Until the end of 2016, NATO conducted counter-piracy activities in full complement of the relevant UN Security Council Resolutions.

NATO vessels conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions to verify shipping activity off the coast of the Horn of Africa, including the Gulf of Aden and the Western Indian Ocean up to the Strait of Hormuz, sorting legitimate maritime traffic from suspected pirate vessels.

(b) Operation Atalanta (CTF 465) by EU (EUNAVFOR, 2018):

The EU launched the European Union Naval Force Atalanta (EU NAVFOR) in December 2008 within the framework of the European Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and by relevant UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) and International Law.

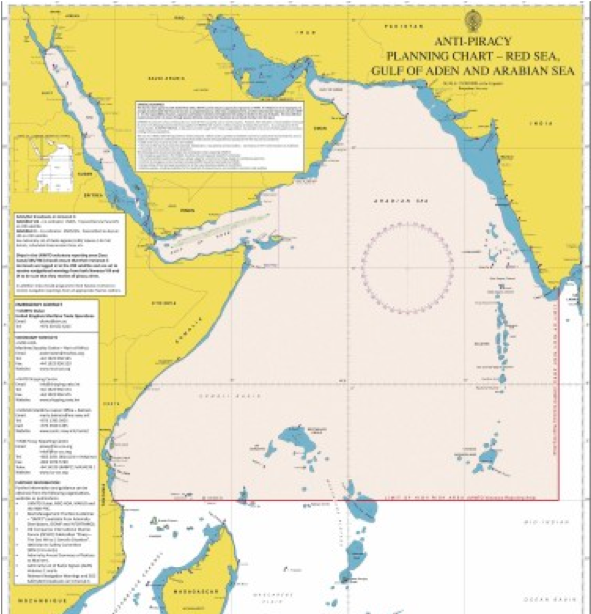

Figure-5 EU Area of Operation for Counter-Piracy (EUNAVFOR, 2018)

EU NAVFOR has an Area of Operations covering the Southern Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and a vast portion of the Indian Ocean, including Seychelles, Mauritius, and Comoros. The Area of Operations also includes the Somalia coastal territory, main territory, and internal waters. Within the Area of Operations, close cooperation with the WFP (World Food Program) and the AMISOM (African Union Mission in Somalia) ensures that no vessel transporting humanitarian aid (or logistics for the African Union mission) shall travel unprotected along the Somalia coastline.

(c) CTF 151 by CMF (CTF-151, 2018):

CTF 151, established in January 2009, has been endorsed under UNSCR 2316 with specific piracy mission-based mandate. Lately it has been empowered to conduct wider maritime security operations in support of CMF which is a multinational naval partnership with 32 member nations with its headquarters located in Bahrain.

CMF comprises three Combined Task Forces (CTFs) which are focused on Counter-Terrorism

(CTF-150); Counter Piracy (CTF-151); and Arabian Gulf Security and Cooperation (CTF-152).

Figure-6 CTF-151 Area of Operation for Counter-Piracy (CTF-151, 2018)

Regarding UNSCR, and in cooperation with CMF coastal states, CTF 151’s mission is to disrupt piracy at sea and to engage with regional and other partners in order to build capacity and improve relevant capabilities to protect global maritime commerce and secure freedom of navigation. CTF 151’s area of operation extends from the Suez Canal in the North West to 15 degrees South.

(d) Independent Deployments:

Additionally, other non-NATO and non-EU countries have, at one time or another, contributed to counter-piracy operations. China, India, Iran, and Russia have all sent ships to the region, sometimes in conjunction with the existing CTFs and sometimes operating independently.

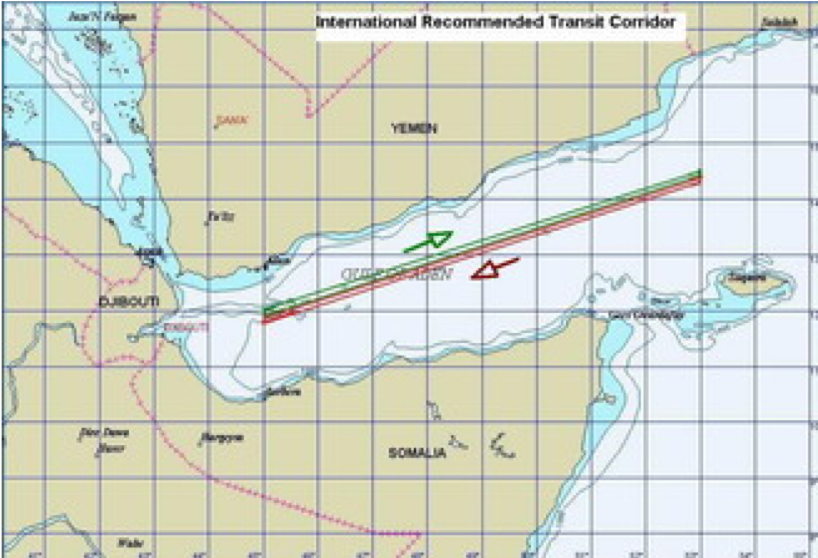

(2) Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) (MSTC, 2018):

The Gulf of Aden is one of the most vulnerable and High-Risk Area for pirate activities: the IRTC is a corridor in which the merchant vessels pass through the Gulf of Aden according to a “Group Transit Schema” coordinated by MSCHOA (Maritime Security Centre – Horn of Africa).

The presence of Naval/Military forces from 3 task forces along with independent deployments in the Gulf of Aden, concentrated on the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC), has significantly reduced the incidence of piracy attack in this area.

Naval/Military forces coordinately operate the ‘Group Transit Scheme’ within the IRTC which is coordinated by MSCHOA. This system’s vessels pass together at a speed for maximum protection during their transit through the IRTC. Some countries offer independent convoy escorts through the

IRTC where merchant vessels are escorted by a warship.

Figure-7 International Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) (MSTC, 2018)

(3) Key Leaders Engagement:

To meet the demands of the region, civil and military actors need to work together. Reaching the population and acquiring their support is often vital to mission success. Key Leader Engagement (KLE) is an important element of Command and Control, and the commander of Task Forces still uses this method to achieve their missions. The Task Forces commanders have been meeting with important local officials, especially during their port visits.

b. The Reasons & Trend of Piracy in Somalia:

The piracy incidents showed a decline after the naval engagements by NATO, EU and CMF assets but the recent attacks indicate that these measures were not a permanent solution to the piracy problem. Because the causes of piracy lie behind land-based problems, lack of legal consequence, chronic unemployment, social acceptance, and opportunity all play a role in supporting this criminal enterprise. For example, illegal fishing off Somalia coasts by other nations leads to the poverty and unemployment rates in Somalia, which are among the root causes of the piracy. But, as a matter of course, naval engagements focus on only pirates, not land-based problems.

In addition to naval engagements, sustainable and long-term solutions by the international community are also vital. Improving the abilities of governance/local forces and supporting the capabilities of onshore community/infrastructures contribute to building long-term solutions which will address not only piracy but also other forms of maritime crime. This is because piracy and other maritime crimes at the Somalia coasts rely heavily on onshore support for infrastructure which provides food, water, fuel and the leafy narcotic khat to the pirates/criminals who guard the pirated ships throughout the ransom negotiation process. The MT Aris 13 which was pirated in 2017 is one of the best examples of why local forces and infrastructure are so important since it was released after only four days and allegedly without ransom payment due to the pressure of Puntland Maritime Police Force. Making an investment in the governance/local forces and onshore community instead of paying millions of dollars as ransom will help to find a permanent solution for the Somalia coasts.

c. Who are the pirates in the Somalia region?

During the counter-piracy operations in which I participated in 2010, we found very interesting results after interviewing a group of pirates:

– The pirates were staying at sea to hijack a ship for weeks without enough food and water, but their income was in a range between Dollar 30,000 and 75,000, which was just to survive on condition that ransom was paid,

– After receiving the ransom, the money they got was deducted because of the food and khat which is a narcotic plant they consumed,

– They said they never mistreated the crew members of the hijacked ships since there were a deduction and a dismissal as a result of mistreatment towards crew members,

– Some of them claimed a big part of the ransom was going a long way in any country such as Kenya and/or Tanzania for the pirate gang leaders,

– Some pirates also claimed that some percentage of the ransom was being transferred to terrorist groups in the region such as Al-Shabbab and terrorist groups tied to Al-Qaeda,

– Most of them said they were doing piracy because they were unemployed and they had a family. These pirates were working as a fisherman before becoming a pirate, but there was not enough fish anymore,

– After spending many days at sea without hijacking a ship, they wanted to be captured by a NATO or EU military ship because these military ships were bringing them on board and giving them humanitarian aid such as food, water, and warm clothes before leaving them on the Somalia coast and destroying their vessels. They also said they were especially afraid of the Russian and Indian Navies because they were brutal and merciless, claiming many of their friends were killed by them.

As a result of interviews; the general view was;

– They obviously needed employment to survive. Fishing, the most important income source of region people, should be maintained by preventing illegal fishing with big trawlers by other countries’ fishermen,

– There were leaders and planners behind the pirates who got a large amount of money,

– The most dangerous part of piracy was the potential to be tied to certain terrorist organizations and the possibility of piracy to transition into violence and killing,

– It was also barbarous to mistreat and/or to kill the surrendered pirates as that is taking advantage of the lack of legal consequence in the region.

4. Piracy in Southeast Asia:

Despite the fact that the Somalia region comes first to the mind when the world thinks of piracy, the Southeast Asia region is also among the most perilous seas for criminals and pirates. The straits and the countless islands in the region are particularly the most dangerous waters.

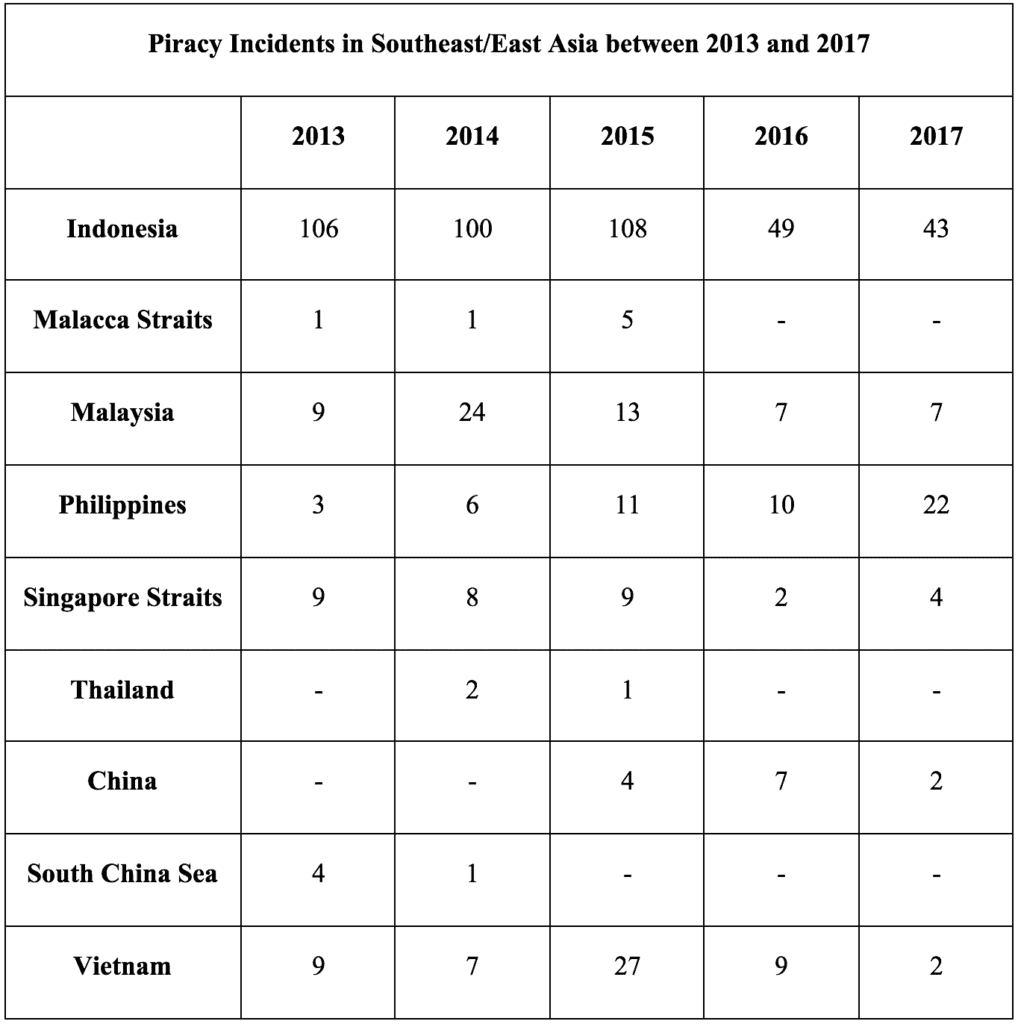

After World War II, Indonesia has become home to the pirate gang leaders. These criminal organizations have offered fishers and seafarers a second profession. By mid-1990s, Southeast Asian pirates have begun to use rifles and machine guns which have given them a reputation for violence. Between 1995 and 2015, the amount of people who were killed during piracy incidents was more than twice the amount of people killed in Africa. However, by the support of local authorities there was a sharp decrease in the incidents when we check the numbers in 2015 and 2016 (ICC IMB, 2018);

– In Indonesia, from 108 to 49,

– In Malacca Straits, from 5 to 0,

– In Malaysia, from 13 to 7,

– In Singapore Straits, from 9 to 2.

In 2017, the region countries, except the Philippines, were able to manage to keep the level of piracy incidents low. Although there is a significant decrease in 2016 and maintaining the same level in 2017,

– Indonesia, with 43 incidents, is in the first place as the country where most of the cases happened,

– There was a significant increase in the Philippines compared to the previous years, from 10 to 22,

– 2 ships were pirated in Malaysia in addition to 1 ship in Indonesia.

Table-1 Piracy Incidents in Southeast/East Asia between 2013 and 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

Stretching from the westernmost corner of Malaysia to the tip of Indonesia’s Bintan Island, the Malacca and Singapore straits serve as global shipping superhighways because of a growing Chinese economy, increasing global maritime trade and becoming a corridor of world oil transit routes. Each year, more than 120,000 ships traverse these waterways, accounting for a third of the world’s marine commerce. Between 70% and 80% of all the oil imported by China and Japan transits the straits. This situation increases the importance of the maritime security and counter-piracy initiatives in Southeast Asia.

As a result, in 2017 most of the attacks in Southeast Asia were due to boarding with 1 in Indonesia and 2 in Malaysia due to hijacking yielding 3 successful attacks in Southeast Asia. Cilacap, Dumai/Lubuk Gaung, Galang, Muara Berau/Samarinda, Off Pulau Bintan in Indonesia and Batangas, Manila in the Philippines are among those with three or more reported incidents. Almost all of the attacks/attempts in Southeast Asia were conducted while the ships were anchored. There were 2 crews killed in the Philippines and almost all attacks in Indonesia and Malaysia; there were crews taken hostage.

a. Counter-Piracy Measures in Southeast Asia:

(1) Regional Cooperation Agreement on Anti-Piracy (ReCAAP):

ReCAAP is the first regional government to agree to promote and enhance cooperation against piracy and armed robbery in Asia. Launched in 2006, it facilitates communication and information exchanges between member countries. Singapore, Japan, Laos, and Cambodia were the first four states to adhere to ReCAAP (ReCAAP ISC., 2018) formally.

Brunei, Cambodia, China, Japan, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, South Korea, and Singapore are among 20 countries that have become contracting parties to ReCAAP, with the United States of America (USA) joining Southeast Asia’s war on piracy in September 2014. However, Indonesia and Malaysia are not members of ReCAAP despite their geographic proximity to these attacks.

(2) Malacca Strait Patrol:

Another regional effort to suppress piracy especially in the Malacca Strait is MALSINDO (Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia) which was introduced in July 2004. Later, Thailand joined MALSINDO in 2008. MALSINDO is comprised of navies from three coastal states in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Conducting coordinated patrol within their respective territorial seas around the Strait of Malacca is its main task. One of the weaknesses of this patrol is that it does not allow the cross-border pursuit of other states territorial sea as it is viewed as interference in other states’ sovereignty. In 2005, significant reductions in the piratical attack around the Malacca Strait were reported.

The reductions of the number of piratical attacks were also influenced by the launching of aerial patrol over the Malacca Straits, known as the “Eyes in the Sky” (EiS) plan. Thailand also joined EiS in 2009. This plan allows the patrolling aircraft to go over the other states’ territorial sea (up to three nautical miles). This measure was enforced as to strengthen the water patrol which has been limited to twelve nautical miles of the respective states.

In 2006, the Malacca Straits Patrols (MSP) was formed which consisted of both MALSINDO and EiS.

(3) ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Measures:

Piracy has also been a concern for ASEAN. Measures to combat piratical attacks have been introduced by some member states of ASEAN.

However, maritime security issues including piracy do not affect the entire membership of ASEAN, so there is no anti-piracy measure at this time, involving all members of ASEAN.

Nonetheless, ASEAN has been committed to discussing issues related to Maritime Security in their meetings. As a result, there are three prominent forums which aim to address Maritime Security: ASEAN Maritime Forum (AMF), ASEAN Regional Forum Inter-Sessional Meeting (ARF-ISM) on Maritime Security, and the Maritime Security Expert Working Group (MSEWG). In addition to these three forums, ASEAN has also produced initiatives to address maritime security threats including piracy.

(4) Military Exercises in the Region: The main goal of these exercises is not directly counter-piracy, but it undoubtedly helps to strengthen regional cooperation and collaboration, increasing the ability to participate nations to work together on (complex multilateral) counter-piracy operations.

(a) Southeast Asia Cooperation and Training (SEACAT) Exercise:

Since 2002, in order to focus on shared maritime security challenges of the region and promote multilateral cooperation and information sharing among navies and coast guards across South and Southeast Asia, Southeast Asia Cooperation and Training (SEACAT) exercises have been conducted annually. In 2017, in addition to the US Navy, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, and Indonesia participated in these exercises.

(b) Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) Exercises:

For 22 years, CARAT has been a bilateral exercise series among the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps and the armed forces of nine partner nations in South and Southeast Asia, including Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Timor-Leste. CARAT is an adaptable, flexible exercise; its scenarios are tailored with inputs from the United States and partner nations to meet shared maritime security priorities, such as counter-piracy, counter-smuggling, maritime interception operations, and port security.

(c) Cobra Gold Exercise:

Cobra Gold is a Thailand/United States co-sponsored, combined task force and joint theatre security cooperation exercise conducted annually in the Kingdom of Thailand. Cobra Gold will strengthen regional cooperation and collaboration, increasing the ability to participate nations to work together on complex multilateral operations such as counter-piracy and the delivery of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. The capabilities of participating nations to plan and conduct joint operations will be enhanced, relationships across the region will be promoted, and interoperability across a wide range of security activities will be improved.

5. Piracy in West Africa (Gulf of Guinea):

The Gulf of Guinea is a hub for global energy supplies with significant quantities of all petroleum products consumed in Europe, North America, and Asia transiting this waterway.

The Gulf is also rich in hydrocarbons, fish, and other resources and is host to numerous natural harbors, largely devoid of chokepoints and extreme weather conditions. On the one hand these attributes provide immense potential for maritime commerce, resource extraction, shipping, and development, but on the other hand, this economic development made the gulf more sensitive in terms of maritime security. The Gulf of Guinea, which has been Africa’s main maritime piracy hotspot since 2011, has become one of the world’s most piracy-affected areas.

As countries in the 5,000-nautical mile (nm) coastline of the Gulf of Guinea increasingly rely on the seas for economic prosperity, the evolving violent attacks on shipping with transnational dimensions call for multilateral remedies.

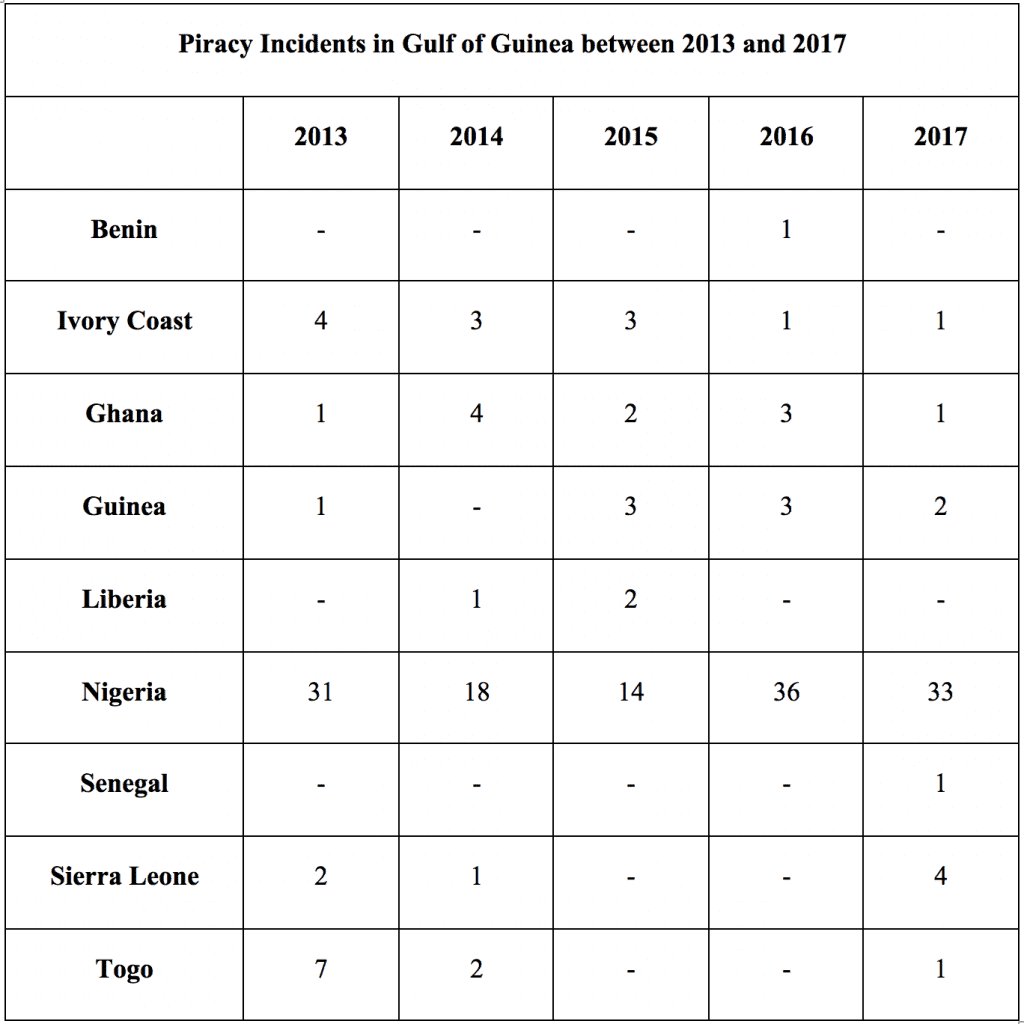

Table-2 Piracy Incidents in Gulf of Guinea between 2013 and 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

The worrying rise in insecurity follows a period where Nigeria was believed to be emerging from maritime risk due to a gradual decline from 31 to 14 in vessel attacks in the area from 2013 to 2015. It was determined that the declines in 2014 and 2015 were the result of the increased naval activities by the Nigerian Navy and the coast guard. Nigeria, as the regional economic power, has developed some initiatives against maritime criminals and pirates in the region.

Despite these initiatives, there was also a significant rise from 14 to 36 incidents from 2015 to 2016, keeping a similar level in 2017 with 33 incidents. In parallel, the Gulf of Guinea recorded a high level of piracy incidents in 2016 and kept at a similar level in 2017 as well.

As a result, in 2017, most of the attacks in the Gulf of Guinea were a result of boarding with some due to being fired upon and attempted, but not successful, hijacking. So, there was no successful attack in the Gulf of Guinea. Lagos in Nigeria is among those with three or more reported incidents with almost all the attacks/attempts conducted while the ships were underway. There was no killed crew, but in almost all of the attacks, there were kidnapped crews in Nigeria.

Additionally, piracy incidents in this area also tend to be more dangerous because they are often well armed and more violent. Additionally, they may kidnap and/or injure the crews. All waters in/off Nigeria are risky; even up to 170 nautical miles from the coast, attacks have been reported in 2017.

a. Counter-Piracy Measures in the Gulf of Guinea:

(1) Obangame Express Exercise:

Obangame Express, conducted by U.S. Naval Forces Africa, is an at-sea maritime exercise designed to improve cooperation among participating nations to increase maritime safety and security in the Gulf of Guinea. It focuses on maritime interdiction operation, as well as visit, board, search, and seizure techniques.

The exercise takes place in the Gulf of Guinea with the participation of 20 African partners: Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo, Cabo Verde, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bassau, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, Morrocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sao Tome and Principe, and Togo.

(2) Regional Initiatives:

Three regional maritime strategies had been adopted by the Economic Community of Central African States (on 29 October 2009); the Gulf of Guinea Commission (on 10 August 2013); and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) (on 29 March 2014). The three organizations agreed on a memorandum of understanding in June 2013, through which they set up a maritime security interregional coordination center in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

This center has to cooperate with the regional maritime security coordination centres established in Pointe Noire, Congo for Central Africa; and Abidjan for West Africa.

(3) Efforts by Nigerian Armed Forces:

Nigerian Armed Forces declared war on general insecurity with counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Guinea among first priorities. The Nigerian Navy has also increased patrols along the coastline and gives authority for the use of firepower on pirates who are in the act of attacking or attempting to hijack ships.

Nigeria has deployed warships and troops in a massive operation to end pirates’ attacks on local and international merchant ships in the Gulf of Guinea. The operation sought to contain a high spate of attacks by thieves on critical oil and gas installations and other misconduct prevalent in the nation’s territorial waters.

(4) The International Response:

The international community and maritime industry have been supporting regional efforts to fight piracy, but most endeavours have been limited to support from the US, European Union, and the International Maritime Organisation. Among the Asian nations, Japan and China have provided some limited support, but as regional observers point out, material resources regarding naval assets and hard-surveillance capabilities have been sorely lacking. The main reason for the international community’s reluctance to get involved in fighting pirates on Africa’s western coast is the absence of pirate attacks on the high seas. Almost all of the reported incidents take place within the maritime territorial limits of the coastal states, where domestic laws apply and only national law-enforcement institutions are authorized to act.

Additionally, it complicates matters in the region since countries like Nigeria and Cameroon have refused to allow merchant ships to bring armed guards into their territorial waters, one of the most effective Best Management Practices.

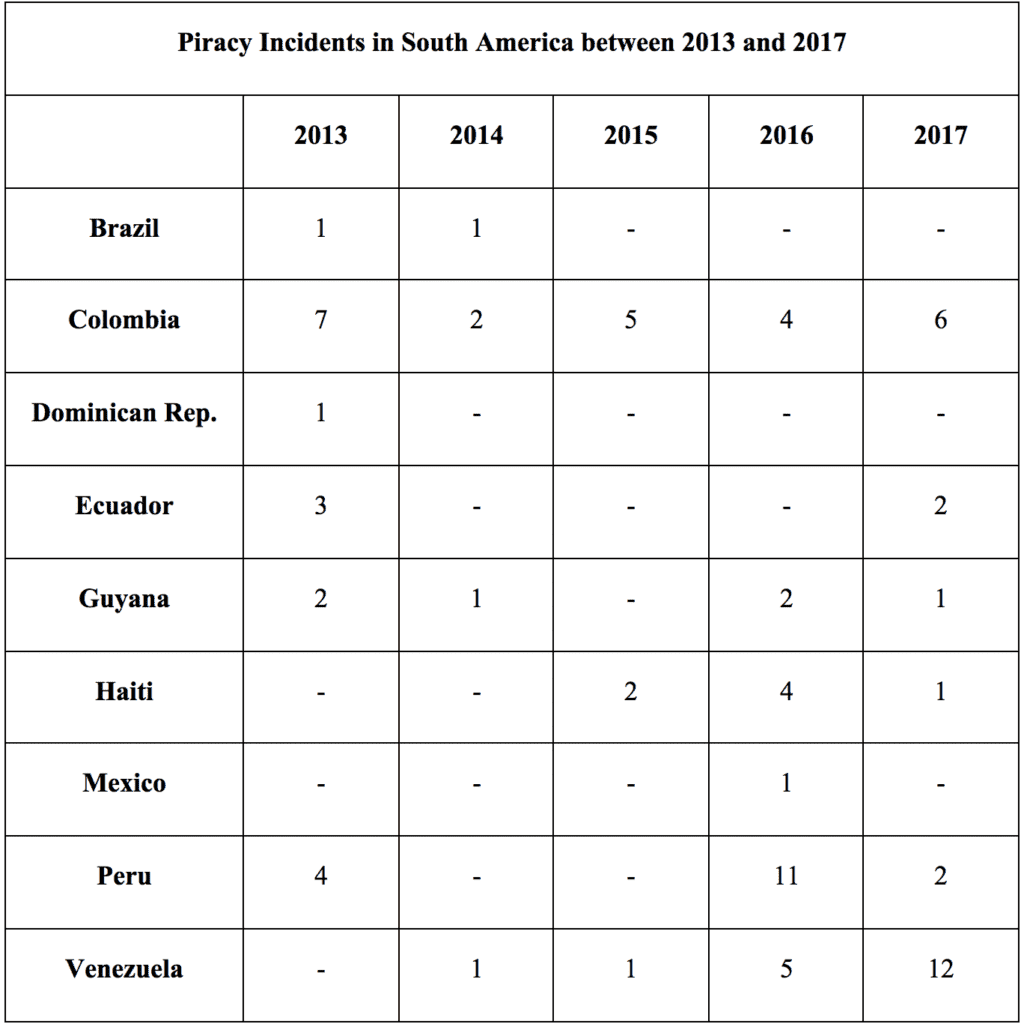

6. Piracy in South America:

Piracy continues to affect vessels operating in South American waters, and much of it is likely to have gone unreported. Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela are among the South American countries that stand out regarding piracy in recent years.

In particular, Venezuela has very rich resources concerning fishing such as tuna, sardines, shark, crab, and octopus. Just like in the Somalia coast, industrial trawlers have hunted in the Venezuelan coast to catch tons of fish creating an unemployment problem leading some of the fishermen to convert into pirates. As a result, there was a sharp increase in piracy attacks in Venezuela in 2017. The increase of piracy attacks in Venezuela began in 2016 when the fishermen were murdered by pirates. Piracy incidence, which was 1 in 2015, has risen to 5 in 2016, and 12 in 2017. It is also thought that many incidents have not been reported. It is worrisome that the incidents may increase day by day. Additionally, Venezuela and the island of Trinidad are separated by only 10 miles of water which is one of the most lawless markets on Earth nowadays. Unfortunately, it is also alleged that the Venezuelan Coast Guard and National Guard are involved in this lawless market.

Colombia also has a situation similar to Venezuela regarding smuggling and drug trafficking adding to the already existing problems of piracy. The Colombian Navy launched patrol by warships to serve in the vicinity of the country’s Pacific waters to defend its sovereignty as well as to provide further support for operations aimed at preventing piracy and drug trafficking. These should help improve the operational capacity of the Navy to assist but only if the vessels are vigilant and report incidents in a timely fashion.

Like Colombia, Peru has significantly developed its control, surveillance and monitoring capabilities in the maritime environment. In this regard, the Peruvian Navy increased surveillance and control of maritime activities to establish maritime security, and they were able to reduce 11 incidents in 2016 to 2 in 2017.

Two incidents have been reported in Ecuador in 2017, the first reports since 2013, although it is likely that many opportunist incidents might go unreported. Particularly in Guayaquil, piracy attacks stopped, but ships were advised to be vigilant.

In addition to piracy in Ecuador, there are high levels of domestic maritime crime, namely the smuggling of narcotics, associated violence towards local fisherman by criminal gangs, and Ecuadorian-Peruvian fishing disputes.

Table-3 Piracy Incidents in South America between 2013 and 2017 (ICC IMB, 2018)

As a result, in 2017, all attacks in South America were a result of boarding, not hijacking. So, there was no successful attack in South America. The ports, Cartagena in Colombia, Puerto Jose and Puerto La Cruz, are among those with three or more reported incidents. Almost all of the attacks in South America were conducted while the ships were anchored. There was no killed crew, but there were hostages, assaults, and injured crews in Peru and Venezuela.

Piracy incidents that take place across South America are largely opportunistic and do not mirror the pirate action groups that operate off the Gulf of Guinea, Southeast Asia, and offshore Somalia. However, it is present within most regional states and can be violent in its nature.

On the other hand, it is really difficult to describe the incidents in South America as either piracy or armed robbery[1]. Unlike the Somalia region, armed robbery, smuggling, and drug trafficking are also very common in these regions.

7. General Precautions Against Piracy:

a. Best Management Practice (BMP):

BMP is a guidance for merchant’s vessels to reduce the chances of being successfully attacked by piracy and/or small, high-speed boats using small arms; rocket-propelled grenades and explosives. BMP offers advice and guidance on avoiding piracy and is targeted at seafarers who intend to travel through the Gulf of Aden, Somali Basin, and the Indian Ocean. Measures include: Maintaining a proactive 24-hour lookout, reporting suspicious activities to authorities, removing access ladders, protecting the lowest points of access, the use of deck lighting, netting, razor wire, electrical fencing, fire hoses and surveillance and detection equipment, engaging in evasive maneuvering and speed during an attack, and joining group transits.

The BMP primarily focuses on preparations that might be within the capability of the ship’s crew or with some external assistance, since pirates cannot hijack a ship if they are unable to board it. The BMP is based on the experience of piracy attacks, and it always requires amendment over time if the pirates change their methods. The following practices are the most basic and effective ones (BMP4, 2011):

(1) Watchkeeping and Enhanced Vigilance: A proper lookout is the single most effective method of ship protection where early warning of a suspicious approach or attack is assured, and where defences can be readily deployed.

(2) Enhanced Bridge Protection: The bridge is regularly the focus for any pirate attack. In the opening part of the attack, pirates direct weapons fire at the bridge to try to force the ship to stop.

(3) Control of Access to Bridge, Accommodation and Machinery Spaces: It is strongly recommended that significant effort is expended prior to entry to the High-Risk Area to deny the pirates access to the accommodation and the bridge.

(4) Physical Barriers: Physical barriers should be used to make piracy as difficult as possible to get onboard the vessels by increasing the height and difficulty of any climb for an attacking pirate.

(5) Razor Wire: Razor wire creates an effective barrier on board where the pirates may climb and attempt to board and take control of the ship.

(6) Water Spray and Foam Monitors: The use of water spray and/or foam monitors has been found to be effective in deterring or delaying pirates trying to board a vessel.

(7) Alarms: Sounding the ship’s alarms/whistle serves to inform the vessel’s crew that a piracy attack has commenced and importantly, demonstrates to any potential attacker that the ship is aware of the attack and is reacting to it.

(8) Maneuvering Practice: Practicing maneuvering the vessel prior to entry into the High-Risk Area will be very beneficial since waiting until the ship is attacked will be too late.

(9) Closed Circuit Television (CCTV): The use of CCTV coverage allows for a degree of monitoring of the progress of the attack as it is difficult and dangerous to observe while under attack.

(10) Upper Deck Lighting: Ships proceed with just their navigation lights illuminated. Once pirates have been identified or an attack commences, illuminating weather deck lighting and searchlights demonstrate to the pirates that they have been observed.

(11) Deny Use of Ship’s Tools and Equipment: Pirates board vessels with little in the way of apparatus other than personal weaponry. It is important to try to contradict pirates the use of ship’s tools or equipment that may be used to hack into the vessel.

(12) Protection of Equipment Stored on the Upper Deck: Any gas bottles or flammable materials are stored before transiting since small arms, and other weaponry are often directed on the bridge, accommodation section, and poop deck.

(13) Citadels: These places provide maximum physical protection to the crew. A Citadel is designed and built to resist a determined pirate trying to gain entry for a fixed period. In case of any crew member being left outside before the citadel is secured, the whole concept of the Citadel approach appears to be lost. If naval/military forces are sure all crew members are secure in the citadel in a pirated ship, then they can apply boarding operation to get control of the ship back. However, the use of citadel cannot guarantee a naval/military response.

(14) Unarmed Private Maritime Security Contractors: The use of experienced and competent unarmed Private Maritime Security Contractors can be valuable depending on voyage risk assessment.

(15) Armed Private Maritime Security Contractors: If armed Private Maritime Security Contractors are to be used they must be as an extra layer of protection and not as an alternative to BMP. If armed Private Maritime Security Contractors are present on board a merchant’s vessel, this fact should be included in reports to UKMTO (the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations) and MSCHOA. On the other hand, some countries do not allow armed private maritime security contractors in their territorial waters.

b. Convention on the Suppression of Unlawful Act (SUA) against the Safety of Navigation (IMO, 2018):

SUA Convention is one of the legal instruments used to combat against illegal acts conducted at sea including piracy. This convention does not precisely aim to address piracy. However, piratical acts are subject to SUA Convention. This convention was initiated after the hijacking of an Italian cruise ship, the Achille Lauro in 1988 which was allegedly motivated by political ends.

Unfortunately, article 101 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was not able to punish the committers as the act did not meet the requirement ‘committed for the private end’. Thus, states find it important to create a legally binding instrument which could arrest criminal acts at sea committed for political and other ends. This convention filled the gap in UNCLOS that confines illegal acts of piracy which requires the two ships involvement as well as it should occur on high seas or other areas beyond the national jurisdiction. According to article 3 SUA Convention, it is against the convention if any person unlawfully and intentionally:

– To seize or exercise control over that ship by force, threat, or intimidation,

– Perform an act of violence against a person on board a ship if that act is likely to imperil the safe navigation of the ship,

– Destroy or cause damage to a ship or its cargo which is likely to endanger the safe navigation of the ship,

– Places or causes to be placed on a ship a device which causes damage to the ship or its cargo,

– Destroys maritime navigational facilities,

– Communicates false information,

– Injures or kills any person in connection with the commission points in the articles above.

SUA Convention also aims to punish its offenders:

– Article 10 (1) expounded that a state is responsible for prosecuting or extraditing the offenders committing one or more of the crimes stated in article 3 of this convention.

– Article 11(1) elaborated that offences in article 3 are extraditable based on the extradition treaty between states. In those scenarios where states do not have treaties of extradition, this convention through article 11 (2) allows states to use the SUA Convention as the legal basis of extradition. Regarding prosecution, the convention reveals in article 6 (1) that state party has the right to establish jurisdiction if the offence meets one of these aspects:

– If the offence is against or on board a ship flying the flag of a state,

– If the attack is committed in the territorial sea as well as the territory of the state,

– If the perpetrator is a citizen of the state.

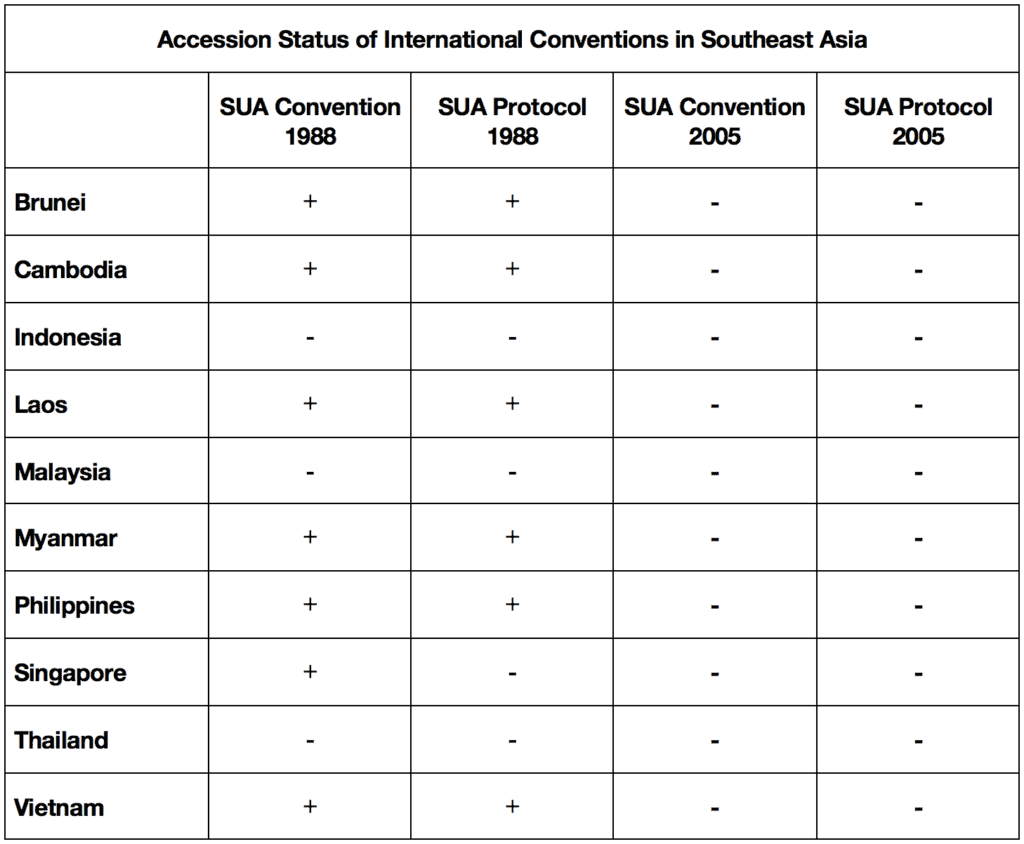

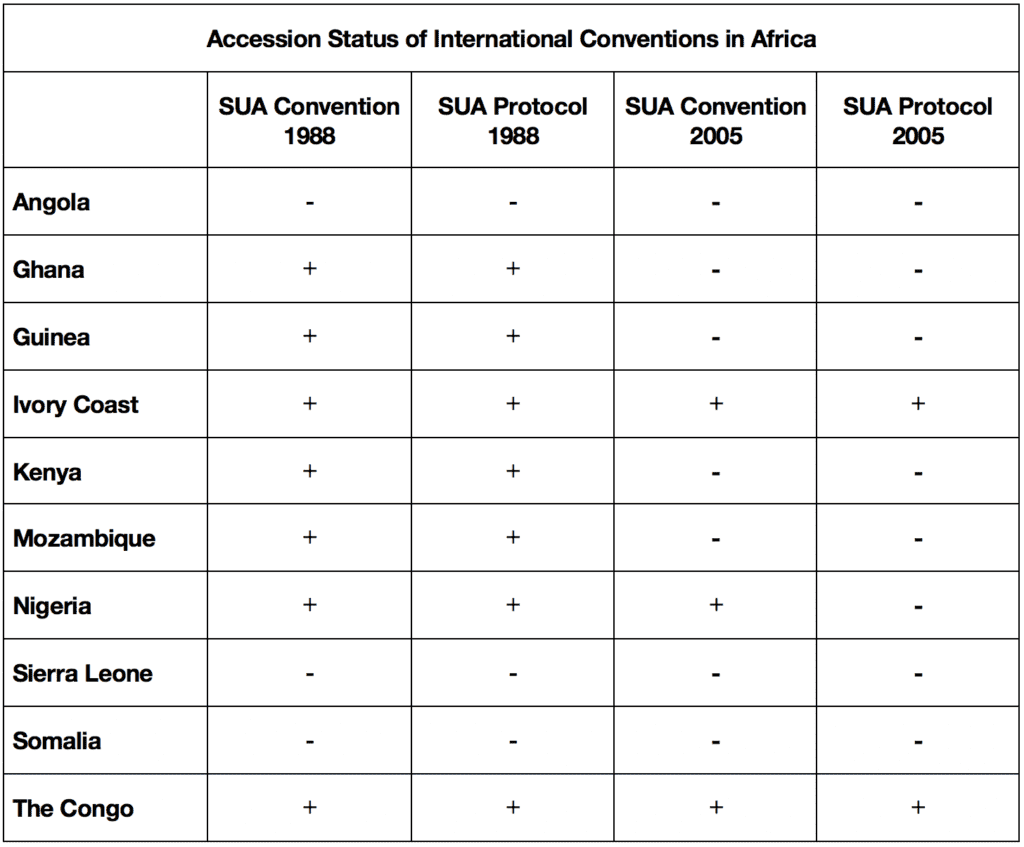

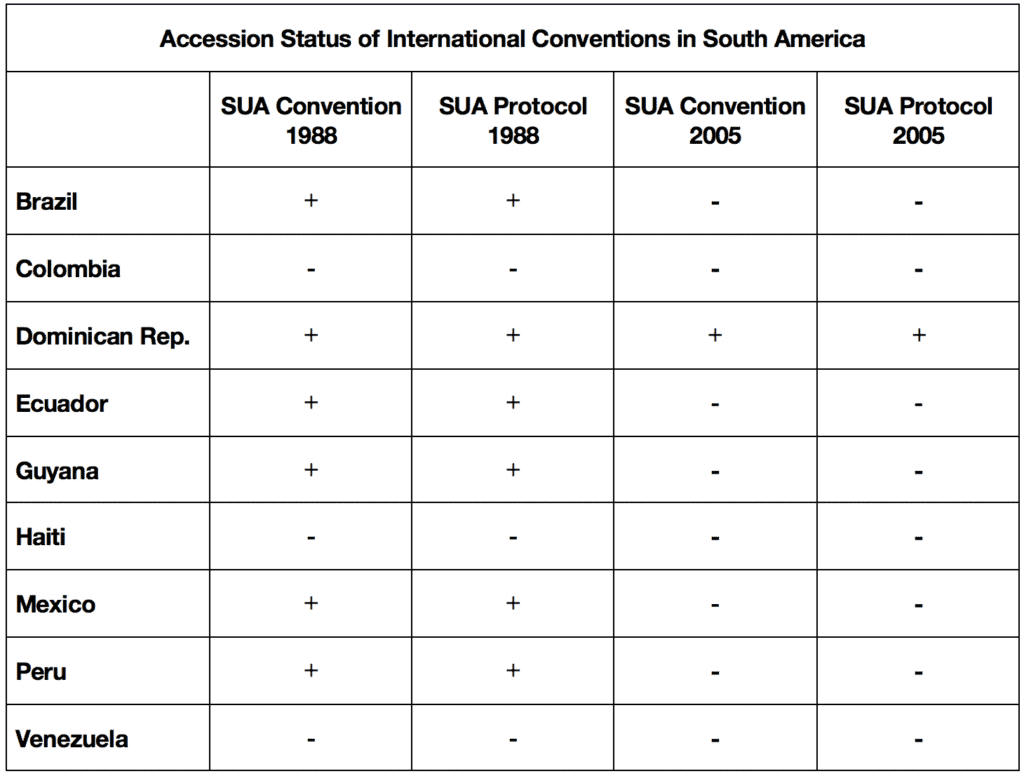

When we check the accession status of International Conventions; Indonesia,

– Malaysia and Thailand in Southeast Asia,

– Angola, Sierra Leone, and Somalia in Africa,

– Colombia, Haiti, and Venezuela in South America are not a party none of 1988 and 2005 SUA Protocol/Convention.

However, Indonesia, Malaysia, Somalia, and Venezuela are among the countries where piracy activities are most experienced.

Table-4 Accession Status of International Conventions in Southeast Asia (IMO, 2018)

Table-5 Accession Status of International Conventions in Africa (IMO, 2018)

Table-6 Accession Status of International Conventions in South America (IMO, 2018)

8. Conclusion:

In order to have a permanent solution to the piracy problem, in addition to counter-piracy military operations, the international community should also focus on land-based problems such as lack of legal consequence and chronic unemployment in the region. For instance, illegal fishing in Somalia waters with big trawlers by other nations should be prevented to avoid creating an unemployment area. Additionally, strong governance/infrastructure and the right to education are also some of the sustainable and long-term solutions.

All the ships planning to pass through high-risk areas should be encouraged to follow the guidance of Best Management Practice and all the countries, especially those suffering from piracy, should be encouraged to be a party to the Convention SUA. Another point of consideration is that ReCAAP should be signed by those regional states in Southeast Asia that have not yet done so.

Moreover, the leaders and planners behind the pirates should be found and neutralized. The most dangerous part of piracy is the potential to be connected with some terrorist organizations and the possibility of piracy to escalate into violence and killing. It is also barbarous to mistreat and/or to kill the surrendered pirates as this would be taking advantage of the lack of legal consequence in the region.

Even though the number of incidents in South East Asia (Indonesia and Philippines) and West Africa (Nigeria) is more than in East Africa (Somalia), Somalia continues maintaining its importance since Somalia pirates still have the capability and capacity to perform attacks.

It has not been ruled out that the merchant ships should vigilantly pass through the coast of South East Asia and West Africa.

The Sri Lankan flagged Bunkering Tanker MT Aris 13 was the first commercial vessel since 2012 to be pirated in the vicinity of Somalia on March 14, 2017. After MT Aris 13, 2 more ships were pirated off the coast of Somalia within 2 weeks, on March 23 and April 1, respectively. The question is whether 3 pirated ships in 2017 represents a new spectre of piracy on the horizon. It can be considered as an indication of a large-scale return to piracy off the Somali coast, but it is not possible to say there will be more frequent attacks in the future. Additionally, the ships, which pass through the Gulf of Aden should inform MSCHOA to use IRTC earlier than its transit. The commander of the task forces should maintain and increase the activities of Key Leader Engagement in the region. Similar corridors in hot-spots in West Africa and Southeast Asia might be established, and the navies of the region countries may support the ships while passing through these corridors.

Over 90% of the world’s trade is carried by sea, and an important amount of this trade uses the route of Bab El Mendeb, Gulf of Aden, Red Sea, Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean. When we take into consideration 3 hijacked ships in the region of East Africa (Somalia, Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden), the counter-piracy operations should continue deterring and disrupting pirate attacks, while protecting vessels and increasing the general security.

It is likely that piracy in Southeast Asia and West Africa (Gulf of Guinea) will continue for years to come and will also remain a security concern for the shipping industry and governments. To combat piracy in these regions, steps in the right direction must be taken, and it requires more cooperation, coordination, and collaboration between countries. The regional countries should launch more joint investigations on piracy crimes in their region and should step in the right direction such as implementing intelligence sharing mechanisms and establishing communication channels.

For South America, it is is largely opportunistic and does not mirror the pirate action groups that operate off the Gulf of Guinea, Southeast Asia, and off-shore Somalia. However, it is present in most regional states and can be violent. It is almost certain that many greater piracy incidents take place across the South America region than is reported but it should not be ignored that most of the incidents might be robbery rather than piracy.

References:

Admiralty. For the latest Security-Related Information to Mariners. Retrieved from. http://www.admiralty.co.uk/srims

Africa centre (2015, February) Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Retrieved from https://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ASB30EN-Combating-Piracy-in-the-Gulf-of-Guinea.pdf

AFRICOM. (2018, February) US Africa Command. Retrieved from http://www.africom.mil/

BMP4. (2011, August) Best Management Practices for Protection against Somalia Based Piracy. Retrieved from http://www.mschoa.org/docs/public-documents/bmp4-low-res_sept_5_2011.pdf?sfvrsn=0

CLYDECO (2015, May) Clyde&Co. Piracy in Southeast Asia. Retrieved from https://www.clydeco.com/insight/article/piracy-in-southeast-asia

CTF 151. Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) Combined Task Force (CTF)-151-Counter Piracy. Retrieved from https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-151-counter-piracy/

C7F. (2018, February) US 7th Fleet. Retrieved from http://www.c7f.navy.mil/

Dryadadmiretime (2017, October) Maritime Crime: South America. Retrieved from http://www.dryadmaritime.com/maritime-crime-south-america/

EUNAVFOR. (2018, February) Counter Piracy off the Coast of Somalia. Retrieved from http://eunavfor.eu/

Hellenic. (2018, February) Hellenic Shipping News, Protection Vessels International: Weekly Maritime Security Report. Retrieved from http://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/protection-vessels-international-weekly-maritime-security-report-46/

ICC IMB. (2018, February) International Chamber of Commerce International Maritime Bureau, Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships – 2017 Annual Report

IMO. (2018, February) International Maritime Organisation, Status of Conventions. Retrieved from http://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/StatusOfConventions/Pages/Default.aspx

ISS. (2017, February) Fighting Rising Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Retrieved from https://issafrica.org/iss-today/fighting-rising-piracy-in-the-gulf-of-guinea

Maritime Ex. (2018, February) The Maritime Executive, Piracy News. Retrieved from https://www.maritime-executive.com/piracy-news#gs.2iOUdeU

MSCHOA. Maritime Security Centre Horn of Africa. Retrieved from http://www.mschoa.org/

MSTC. Maritime Security Transit Corridor. Retrieved from https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/maritime-security-transit-corridor-mstc/

NATO-OOS. (2016, December) NATO Operation Ocean Shield. Retrieved from https://www.mc.nato.int/missions/operation-ocean-shield.aspx

OBP. (2017, January) Oceans Beyond Piracy, The State of Maritime Piracy. Retrieved from http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/latin-america

ReCAAP ISC. (2018, January) The Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Information Sharing Centre. Retrieved from http://www.recaap.org/

Time. (2014, August) The Most Dangerous Waters in the World. Retrieved from http://time.com/piracy-southeast-asia-malacca-strait/

UOW. (2013, December) The University of Wollongong, Combating maritime piracy in Southeast Asia from international and regional legal perspectives: challenges and prospects. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2062&context=lhapapers

[1] Armed robbery (IMO definition) “Any unlawful act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, threat thereof, other than an act of ‘piracy’, directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such ships, within a state’s jurisdiction over such offences.”