By Uğur ORAK, Non-resident Fellow at Beyond the Horizon, Ph.D Candidate and Kasim DOGAN, Visiting Fellow at Beyond the Horizon, PhD

1. Introduction

If we can determine what drives people to commit such heinous crimes, it is suggested, perhaps we can change their behaviour.[1]

While it has been nearly two decades since the beginning of the global war on terrorism, the experiences gained in successive processes have revealed the fact that destroying terrorists in the battlefield is not a sufficient measure to neutralize the global threat of violent extremism. Even if a terrorist organization is deactivated in the battlefield—as is the case with Al-Qaida and ISIS examples—similar extremist ideas can proliferate in a different domain with a different organization. In this respect, along with the physical efforts exhibited in the combat zone, a successful war on violent extremism should also strategically focus on why individuals adopt and internalize the extremist visions and, in turn, engage in terrorist acts. To put it another way, as Borum emphasized, we should “seek to understand not only what people think, but how they come to think what they think, and, ultimately, how they progress—or not—from thinking to action.”[2] This perspective provides an important hint regarding how to prevent the emergence of a new terrorist organization and to avert individuals’ acceptance of radical views after the ISIS falls. If we can clearly lay bare how individuals come to adopt radical views and participate in ISIS—in particular, and terrorist organizations—in general, we can take effective precautions to overcome this crucial issue. In line with this viewpoint, this policy report seeks an answer to the question of how we can stem the tide of a reemergence of violent extremist views after the fall of ISIS.

Extant academic research and policy reports have exerted a notable effort in explaining the triggers of participation in terrorist organizations. Some studies—especially studies from political science—have generally concentrated on the role of the ideology and the religion. Yet, the ideological transformation almost always takes place after joining a radical group and the ideology functions merely as a vehicle to be a violent extremist. The main question should be why these individuals feel a need to belong to a radical group and to which processes they are exposed until deciding to join radical groups. The “ideology” approach is therefore not sufficient to explain involvement in violent extremism. Explanations of religion as a trigger of violent extremism are also problematic. Recently, several academic studies demonstrated that the religion was seldom, if ever, the root cause of violent extremism.[3] [4] [5] [6] Along with these researches, some other studies examined the issue from a sociological perspective and prioritized the illiteracy as the main cause of violent extremism. While this approach could be utilized for extremists who reside in Western countries, however, the unique case of ISIS clearly showed us that the average educational attainment of its members was higher than that of the public in source countries.

Aforementioned studies have generally failed to present a comprehensive model that explains the social processes and accounts for the variability of individual and social-structural factors—facilitating the engagement in violent extremist actions—for different extremists residing in different countries. Thus, the current study intends to fill this gap through providing a comprehensive sociological model which would be suitable for explaining the process of radicalization both for individuals who reside in source countries (Middle East) and for those who reside in Western countries. To sum up, the purpose of this policy report is two-fold: (1) to elucidate the nature of the sociological process by which an individual adopts radical views, joins an extremist organization, and engage in violence; and (2) to extend policy recommendations towards the effective sociological measures that should be taken to undermine the process that might culminate in violent extremism.

2. THE PROCESS OF RADICALIZATION INTO VIOLENT EXTREMISM

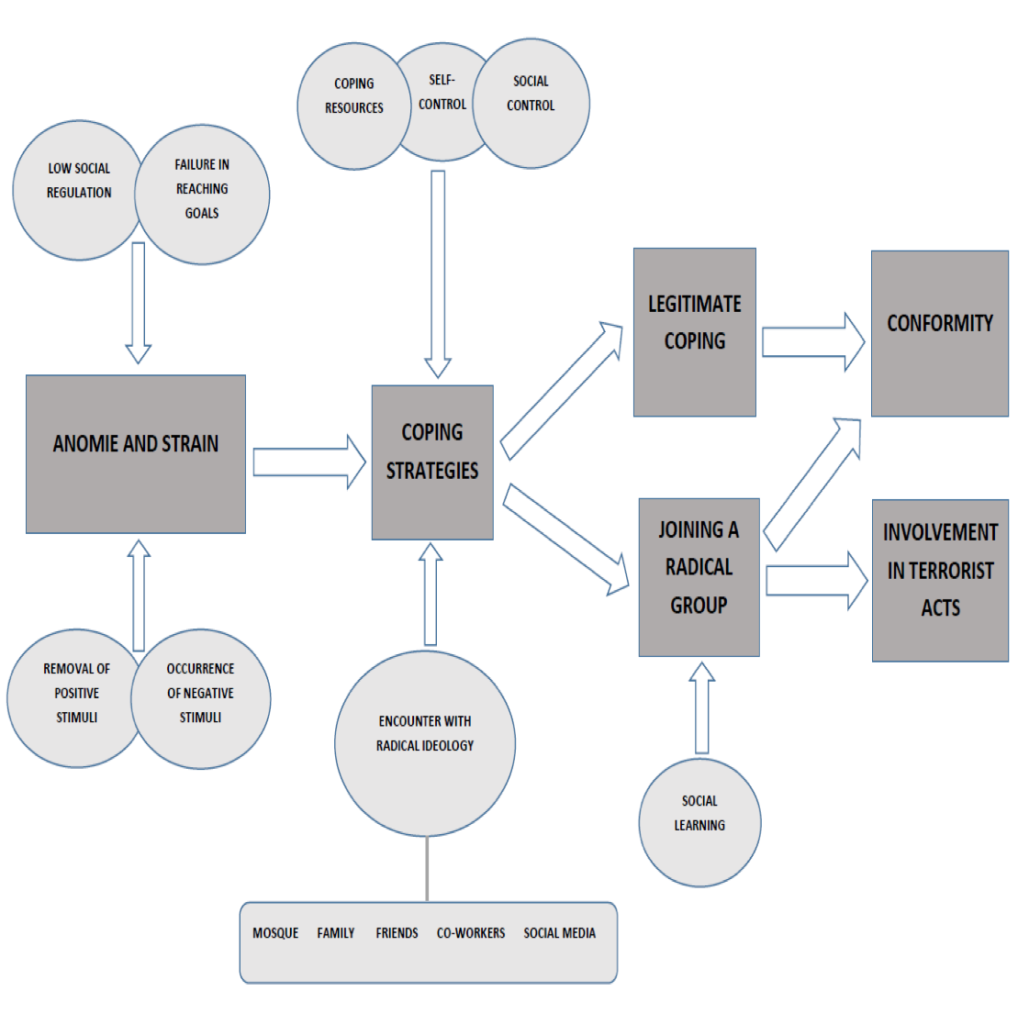

The academic literature on radicalization and violent extremism has primarily concentrated on the question of why individuals adopt the beliefs that push them towards engaging in terrorist activities and violence. Although some early studies have considered the radicalization as a stable condition that is arising out of personal or mental abnormalities, much of the research has viewed it as a dynamic process. The nature of the process, however, has been poorly understood. Extant research has generally focused either on individual/psychological or ideological/religious aspects of the issue, and ignored the sociological process by which an individual adopts and internalizes violent extremist views. Thus, the current study offers a comprehensive sociological pathway model that would account for both micro and macro-level explanations of and contextual variability in the process that would culminate in terrorist activity. Figure 1 represents our pathway model consisting of four interrelated phases, beginning with the experience of anomie and strain and resulting in either conforming or terrorist behavior. Each phase is also impacted by a variety of factors. Within this pathway model, engagement with the terrorist activity is considered not as the outcome of a single decision but the consequence of a dialectical process that gradually propels an individual towards internalization of violence over time.

Figure 1: Pathway Model of Radicalization into Violent Extremism

2.1 Phase 1: Experience of Anomie and Strain

“Theory can serve as an azimuth for exploring complex questions. There are many possible theoretical-analytic frameworks that might be applied to the radicalization process.”[7] Based on the propositions of Anomie and Strain Theories, our proposed pathway leading an individual to engage with violent extremism begins with the experience of anomie (at the macro-level) and strain (at the micro-level). Historical origins of Anomie and Strain Theories can be traced back to Durkheim’s seminal works, “Division of Labor in the Society” and “Suicide”.[8] [9] According to Durkheim, there are two important factors connecting individuals to socially valued norms and preventing them from breaking these norms. These factors are social integration and social regulation. Social integration refers to individuals’ ties with the broader society, while social regulation is external constraints restraining individuals from deviating from social norms.

For Durkheim, when the levels of social integration and social regulation are too low or too high, societies face with important challenges. In his seminal book, “Suicide”, he explains this situation in detail. He states that there are four different types of suicide, a self-harming behavior deviating from institutionalized norms. These are; (1) egoistic suicide, which occurs when individual’s integration with broader society is too low, (2) altruistic suicide, which occurs when individual’s integration with the society is too much; i.e. suicide bombers, (3) fatalistic suicide, which occurs when the level of social regulation is too high that causes individuals to lose their self-identity and meaning of life, and (4) anomic suicide, which occurs when the level of social regulation is too low. From this point of view, it could be understood that anomie refers to a consequence of low social regulation, or in other words lack of constraints keeping people from committing deviant conducts. Anomie, as a French word, can be shortly translated into English as “normlessness”. According to Durkheim, when social norms lose their regulatory power over individuals’ actions, that society can be called as anomic and individuals can be expected to deviate from socially valued norms. He states that anomic situations can emerge at the times of rapid social, economic, and technological changes. At the time of economic depressions, for instance, individuals are expected to restrain their needs, limit their spending, and comply with the requirements of economic depression. Most individuals, however, cannot simultaneously adjust their situations to these new norms, thus they would be more likely to commit deviance or crime to reach their financial goals.

Durkheim’s approach could provide an important insight into understanding why an individual chooses to join a terrorist group and commits terrorist acts. A close examination of different cases of terrorism shows us that terrorist organizations have generally come to the existence immediately after rapid social changes and as a result of low social regulation, which is called anomie. Al Qaeda, for instance, was formed in 1988, during the last years of Soviet invasion of Afghanistan lasted over nine years from December 1979 to February 1989, during which tens of thousands of people were killed, a lot more were jailed and fled the country. We can see the same process in the case of ISIS. The emergence of ISIS coincides with the bloody Syrian Civil War, which was an ongoing multi-sided armed conflict in Syria fought primarily between the government of President Bashar al-Assad, along with its allies, and various forces opposing the government. Both processes in Afghanistan and Syria were accompanied by significant changes in social and economic conditions and by the disruption of social regulation. In other words, at the macro-level, one can conclude that the emergence of both terrorist groups was a consequence of anomie in source countries.

Photo by Pixabay

Durkheim’s concept of anomie was firstly considered in the criminological area by the prominent criminologist Robert Merton. Merton stated that Durkheim’s concept of anomie was a more macro-level concept, which was related to rapid changes taking place in the social structure at a specific period of time. He presented the concept of “strain” as an ongoing form of stress, as a useful tool to understand individual differences in deviance engagement.[10] For Merton, for a long time, American ideology has exerted a substantial pressure to individuals and stimulated them to wealth accumulation, pecuniary success, and ambitiousness. However, social status and social stratification in the American system blocked the ways of achieving pecuniary success for some individuals. In other words, legitimate means to reach legitimate ends are not available for all people, especially for those in the lower class status and having a different racial identity. This situation caused a strain (or commonly known as stress) on these individuals. According to Merton, individuals who are exposed to strain can develop five forms of modes of adaptation. These are; (1) conformity, by which an individual may choose to conform with both institutionalized goals and institutionalized means, (2) innovation, by which an individual may accept the legitimacy of institutionalized goals, but choose unconventional means (i.e. drug dealing) to achieve these goals, (3) ritualism, by which an individual accepts the institutionalized means, but do not attempt to reach institutionalized goals; they remain poor, but proud, (4) retreatism, by which an individual may neither accept institutionalized goals nor means, they retreat from interaction with others (i.e. alcoholics); for Merton, these are “sociologically true aliens”, and (5) rebellion, by which an individual may not accept the legitimacy of institutionalized goals and means, and attempt to change them (i.e. terrorists or marginal groups). Although Merton’s theory provided an insight into understanding individual differences in deviant engagement, it has been criticized for being merely economically-oriented, and regarding the main cause of deviance as individuals’ failure in reaching pecuniary goals.

For Agnew, strain as a consequence of one’s failure in reaching pecuniary success can only partially account for his/her engagement in deviance.[11] Thus, he stated that there are three main sources of strain including (1) goal blockage, (2) occurrence of negative or noxious stimuli, and (3) removal of positive stimuli. Goal blockage refers to one’s failure in reaching economic, social, or cultural goals. The occurrence of negative stimuli refers to the emergence of the stressful event that is negatively affecting individuals’ lives such as broken relationships with a romantic partner. Removal of positive stimuli refers to the loss of anything that affected individuals’ lives positively such as the death of a parent. Removal of positive stimuli can sometimes be same with the occurrence of negative stimuli. In sum, Agnew states that these are three main sources of strain, which may lead individuals to engage in deviance. For Agnew, however, the strain does not directly lead to deviance or crime. Rather, negative affective states or mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, anger, despair buffer the effects of strain on deviance. In other words, strain leads to negative affective states, and in turn they lead to deviant engagement. Agnew, on the other hand, states that there might be hundreds of types of strain, but not all of them lead to deviance. At this point, four dimensions of strain gain importance. These dimensions are; (1) duration, (2) magnitude, (3) recency, and (4) clustering. Strains that are ongoing or continuous, high in magnitude, more recent, and clustered in time are more likely to lead negative affective states and deviance.

Merton’s and Agnew’s propositions on the relationship between strain and deviance could provide an insight into explaining the causes of engagement with terrorism at the micro-level. Particularly Muslim individuals residing in European countries experience a significant amount of strain or stressful experiences. When we examine the European countries from where a lot of individuals joined the ISIS, for instance, we can clearly see that native people in these countries have a tendency to exhibit negative attitudes toward Muslim inhabitants and refugees. Since the cultural values in Europe are very different from those in Syria, refugees would have serious adaptation problems. This leads natives in European countries to adopt negative attitudes toward refugees. Religion is also an important component determining natives’ attitudes. Because of the negative image of Islam among the vast majority of European natives due to inhuman activities of radical terrorists, refugees or Muslim inhabitants are generally stigmatized as being poor, illiterate, and potential terrorists. According to Global Attitudes Survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2015, most people in European countries have negative attitudes toward refugees; the rates of people with negative attitudes are 29 percent in Germany, 46 percent in Spain, 52 percent in France, 69 percent for Italy, and 70 percent for Greece. These negative attitudes might turn into a physical violence and grassroots movements. As a destructive result of this stigmatization, refugees could gang up against natives or join an existing terrorist group. In 1975, for instance, Chilean refugees, who had fled to Argentina as a result of a military coup, took a number of hostages in Buenos Aires to protest the harassment they were exposed by native people.[12]

Another source of strain Muslim people face in European countries is the problems resulted from dismal living conditions imposed upon refugees. Milton and colleagues noted that most refugee centers do not have sufficient amount of resources and health-care infrastructure.[13] Given that refugees are the group of people whose physical and mental health suffers due to destructive war conditions, a new country that is incapable of improving their material well-being and health conditions would further exacerbate their negative emotionality. This might cause refugee population to turn to radicalism and engage in conflicts against host countries. In 1965, for example, Rwandan refugees who had fled Burundi due to the political turmoil assassinated the Burundi prime minister because of government’s unsuccessful policies to take care of refugees. As could be recognized from this example, adverse or unsuccessful policies implemented by governments could lead refugees to increased negative emotionality, radicalization, and ethnic conflicts.

In sum, in our model, the pathway to terrorist activity begins with an experience of anomie and strain. However, not all individuals who have been living in an anomic society or experienced a variety of sources of strain exhibit terrorist behavior. Our model proposes that individuals who face anomie and strain might develop several coping strategies—either legitimate or illegitimate—depending on the availability of several factors. Thus, the second phase of the process of radicalization into violent extremism refers to the development of coping strategies against experienced anomie and strain or stressful experiences.

2.2 Phase 2: Coping Strategies

Thoits states “that “stress” or “stressor” refers to any environmental, social, or internal demand which requires the individual to readjust his/her usual behavior patterns.[14] As stressors accumulate, individuals’ abilities to cope or readjust can be overtaxed, depleting their physical or psychological resources, in turn increasing the probability that psychological disorder and deviant behaviors will follow.[15] [16] The relationship between stress exposure and deviant behaviors, however, is not strong because individuals have extensive coping resources to help them handle stress.

Coping resources are social and personal characteristics upon which people may draw when dealing with stressors.[17] Resources reflect a “latent dimension of coping because they define a potential for action, but not action itself.”[18] There are mainly three coping resources as; (1) social support, (2) sense of control or mastery over life, and (3) self-esteem. These coping resources are presumed to influence the choice and/or the efficacy of the coping strategies that people use in response to stressors. Coping strategies consist of behavioral and/or cognitive attempts to manage specific situational demands which are appraised as taxing or exceeding one’s ability to adapt. Coping efforts may be directed at the demands themselves (problem-focused strategies) or at the emotional reactions which often accompany those demands (emotion-focused strategies). Most investigators assume that people high in self-esteem or perceived control are more likely to use active, problem-focused coping responses; low esteem or perceived control should predict more passive or avoidant emotion-focused coping. A related concept is that of coping styles, which are habitual preferences for approaching problems; these are more general coping behaviors that the individual employs when facing stressors across a variety of situations (e.g. withdraw or approach, deny or confront, become active or remain passive).[19] In general, problem-focused coping is more likely when situational demands are appraised as controllable; emotion-focused coping is more likely when demands seem uncontrollable. One could argue that people high in self-control or self-esteem should be more likely to appraise specific situations as controllable and thus to engage in problem-focused coping; those low in these personality resources should more often perceive problems as uncontrollable and thus engage in emotion-focused coping. In the cases of terrorist activities, it is generally supposed that individuals who engage in these activities are generally destitute of coping resources and develop emotion-focused coping strategies.

Another factor that might influence the way a strained individual develop a coping strategy is social control. Social control theory proposes that “delinquent acts result when an individual’s bond to society is weak or broken.”[20] There are four relevant dimensions of the social bond including; (1) attachment, (2) commitment, (3) involvement, and (4) belief. Attachment refers to emotional ties between an individual and other people and nonhuman objects in the society. Commitment refers to individual’s goals and expectations from the life. Involvement refers to individuals’ efforts to participate in noncriminal pursuits. And finally beliefs refer to individuals’ beliefs in cultural values in the society. Based on social control theory’s approach, we can conclude that individuals who lack attachment to conventional others, commitment to conventional goals of the society, involvement in conventional pursuits, and beliefs in values of the society are more likely to develop illegitimate coping strategies such as joining a radical group.

Although social control theory has been empirically supported by numerous researches, Hirschi believes that this theory is not capable of explaining stable individual differences in propensity to engage in crime and delinquency.[21] Drawing on findings from relevant surveys, he states that there is a curvilinear relationship between crime and age. This suggests that, in any circumstances, criminal engagement reaches a peak level in adolescence and early adulthood, and then it sharply decreases. However, for some individuals, criminal engagement persists over the life course, and does not decrease in adulthood. Thus, Hirschi concludes that this is due to the effects of low self-control. From this point of view, he also notes that self-control is acquired in childhood and individuals do not engage in criminal activity in next periods of their lives if they appropriately acquire self-control in their childhoods. He defines self-control as “the tendency to avoid acts whose long term costs exceed their momentary advantages.”[22] Thus, self-control is another significant factor impacting the way an individual shape coping strategies against anomie and strain.

While an individual attempts to develop coping strategies against experienced anomie and strain, he or she may also be influenced by radical ideologies. They may find the opportunities of coping in the “collective ideology of one’s group that also identifies the grievance or loss of group significance in need of redressing.”[23] If such ideology identifies violence and terrorism as the justifiable means to cope with anomie and strain, individuals may support and commit to terrorism and violence. Individuals may encounter these radical ideologies in a variety of ways. In some cases, they may encounter the terrorism-justifying ideology through some individuals in their informational ecology which may include mosques, family, friends, or co-workers. In a yet different instance, the individual may encounter the terrorism-justifying ideology through social media.

2.3 Phase 3: Legitimate Coping vs. Joining a Radical Group

As was stated in the previous section, individuals who face anomie and strain might develop several coping strategies—either legitimate or illegitimate—depending on the availability of several factors such as availability of coping resources, self-control, social control, and encounter with radical ideologies. Studies indicate that most of the individuals develop legitimate coping strategies and choose to comply with conventional norms of the society. Some of them, however, develop illegitimate coping strategies including joining a radical group. In a radical group, individuals experience a socialization process by which they internalize the radical notions and get ready to accomplish tasks given by the group. This socialization is accompanied by a learning process, which is proposed by the Social Learning Theory.

Just as we learn reading and writing from our parents, friends or teachers, criminal behaviors are also learned by others in a similar process.[24] Social Learning Theory, which is basically based on this idea, was firstly mentioned by Edwin H. Sutherland as Differential Association Theory.[25] Sutherland, however, did not explain the learning process of criminal behavior in detail. Subsequently, Akers expanded the theory by specifying the basic structure of learning process and renaming it as Social Learning Theory.[26] According to Social Learning Theory, “the learning process consists primarily of instrumental learning that occurs either directly through rewards and punishments for behavior, or vicariously by imitation or the observation of the behavior, and the consequences that the behavior has for others.” According to Akers and colleagues, there are mainly four phases through which criminal or deviant behaviors are learned.[27] These are; (1) differential association, (2) imitation, (3) definition, and (4) differential reinforcement. Differential association refers to the interactions with a group of criminal or noncriminal individuals, and it comes first in the ranking of social learning process. Considering the terrorism example, individuals firstly interact with a group of people who adopt radical views. Then they begin using verbalizations and justifications by imitating other people in the group. At this point, individuals define their behaviors by taking into account the rewards and punishments as potential consequences of their behaviors. If they believe that momentary rewards provided by the terrorist behavior exceed its potential long-term disadvantages, after a while, their behaviors are differentially reinforced, and thus learned. Once the terrorist behavior is learned and reinforced, it gets pretty difficult for an individual to return to conformity, although there is still a possibility to get de-radicalized.

2.4 Phase 4: Conformity vs. Terrorist Activity

The final stage of our proposed pathway of radicalization into violent extremism is conformity vs. terrorist activity. As was stated before, most of the individuals experiencing anomie and strain develop legitimate coping strategies and choose to comply with conventional norms of the society. Some of them, however, develop illegitimate coping strategies that may culminate in terrorist activity. The terrorist activity might include several acts varying from participating in passive duties to active participation in conflicts to even self-sacrifice. Once an individual engage in terrorist activity, it is nearly impossible for him or her to return to conformity.

3. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

In the preceding section, we attempted to answer the question of why an individual comes to adopt terrorism-justifying ideologies by offering a pathway or developmental model which reveals the sociological process. Now, we will turn to another critical question: “How can we prevent adoption and internalization of these ideologies?” In other words, we will offer effective policies to block the pathway through which an individual engage in terrorist activity. As was stated previously, once individuals joined a radical group, internalized radical viewpoints (phase 3), or engaged in terrorist activities (phase 4), it is pretty difficult to deradicalize them. Ideally, the goal of deradicalization is to push individuals towards changing their belief system, rejecting the extremist ideology and embracing a moderate worldview. This is difficult with extremists, because the requirements of the ideology are generally regarded as religious obligations. For this reason, we believe that a successful war on violent extremism should focus on the first and the second phases. From this point of view, we offer two general policies that should be implemented concurrently towards phase 1 and phase 2 of the pathway model.

3.1 Potential Policies towards Phase 1

Before explaining the potential policies that can be implemented to prevent anomie and strain, it is important to note the intercontextual variabilities in the engagement with terrorism-justifying behavior. Terrorist organizations (i.e. ISIS) attract individuals to join the group from two sources; (1) countries wherein the terrorist organization come into the existence, which we call “source countries (i.e. Iraq and Syria)”, and (2) countries external to source countries, wherein the terrorist organization attempts to recruit new militants (i.e. European countries). While individuals who join the terrorist organization in source countries generally experience “anomie”, the primary cause for those who join the terrorist organization from other countries is “strain”. Thus, we should focus on macro-level policies for those residing in source countries to suppress the anomic condition, and concentrate on micro-level policies for those residing in European countries to overcome the strain.

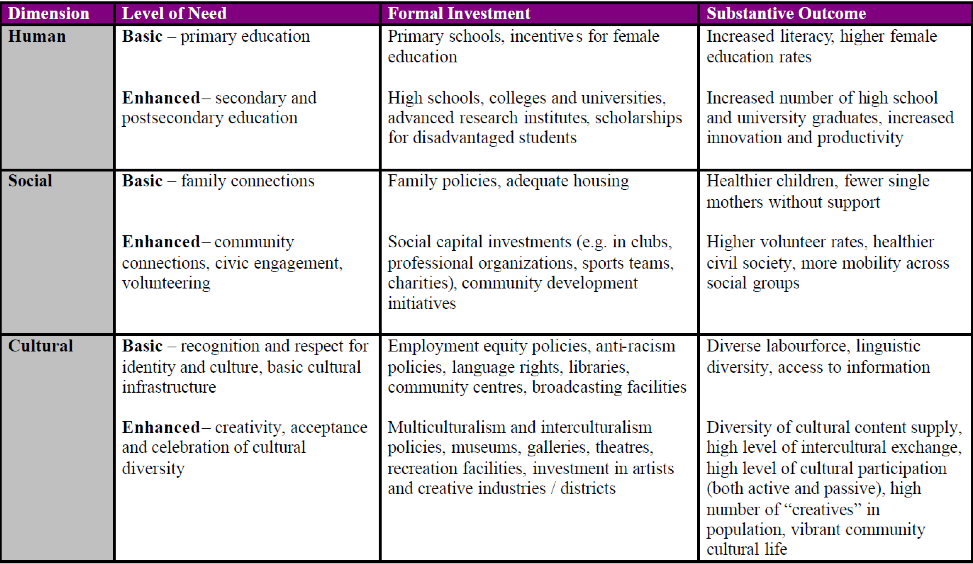

The concept of anomie encompasses social regulation and social integration. Thus, to prevent anomic conditions in source countries, we should focus on increasing social regulation and social integration. Social regulation is directly linked to the country’s political conditions. In order to promote the social regulation, it is essential for a nation to have a properly functioning state structure. The second aspect is social integration. Durkheim suggested that the problem of anomie could be overcome through social associations based on professions that would socialize with one another.[28] He believed this would give people a sense of belonging, vital to preventing anomie. In his study, Suicide, Durkheim showed that Catholics committed suicide less often than Protestants because of the sense of community developed within Catholic churches. Thus he advocated the importance of communities within the larger society, through which people can share common values and standards of behavior and success, and so avoid feelings of isolation and the development of anomie. To promote social integration in the society, M. Sharon Jeannotte’s model of social integration might also provide us with an important prospectus (see Figure 2).[29]

As was explained earlier, strain is the major cause of joining a terrorist organization for individuals living in European countries. There are three main sources of strain including (1) goal blockage, (2) occurrence of negative or noxious stimuli, and (3) removal of positive stimuli. There are two primary factors leading Muslim individuals to experience strain in European countries that block the ways they reach their goals, create negative stimuli, and suppress positive stimuli. The first factor is stigmatization. Because of the negative image of Islam among the vast majority of European natives due to inhuman activities of radical terrorists, refugees or Muslim inhabitants are generally stigmatized as being poor, illiterate, and potential terrorists. As relevant statistics indicated, native people in these countries have a tendency to exhibit negative attitudes toward Muslim inhabitants and refugees. As a destructive result of this stigmatization, refugees could gang up against natives or join an existing terrorist group. Thus, it is important to stop stigmatization activities towards Muslim inhabitants in order to prevent them from joining terrorist groups.

Another source of strain Muslim people face in European countries is the problems resulted from dismal living conditions imposed upon refugees. Given that refugees are the group of people whose physical and mental health suffers due to destructive war conditions, a new country that is incapable of improving their material wellbeing and health conditions would further exacerbate their negative emotionality. This might cause refugee population to turn to radicalism and engage in conflicts against host countries. This indicates that a successful effort towards preventing individuals from joining a terrorist group should focus on how to improve their material and health conditions.

Figure 2: Elements of Social Integration

Source: Jeannotte, 2008

3.2 Potential Policies towards Phase 2

An alternative policy we propose should focus on the second phase of the pathway model. In other words, we should implement policies that are promoting the legitimate coping strategies. To be able to accomplish this task, our efforts should be directed towards (1) promoting coping resources including self-esteem, mastery over the life, and social support, increasing self-control and social control, and (2) blocking the ways through which terrorist organizations attract individuals’ interests. To promote coping resources, we should focus on social networks the individual has. To increase self-control, we should direct our attention to the education of children in a family environment. To increase social control, we should find ways of increasing individuals’ attachment to conventional others, commitment to conventional goals of the society, involvement in conventional pursuits, and beliefs in values of the society. And finally, to block the ways through which terrorist organizations attract individuals’ interests, we should concentrate on individuals’ informational ecology (mosques, family, friends, co-workers) and social media. Recent studies show that social media is the primary ground where individuals encounter the terrorism-justifying ideologies. For this reason, how individuals adopt radical ideologies through social media and the effective policy measures that could be taken against terrorist groups’ use of social media is subsequently examined in a detailed section in the current policy report.

4. SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media needs to be taken into account separately due to its force multiplier effect. That is neither a way of symmetric nor an asymmetric warfare, it is more like a way of hybrid warfare as it is a kind of game-changer. Thompson reveals the importance of the matter in a self-contained way by stating that “social media easily connects people very quickly with a wide audience, the synergy creates a movement en masse of like-minded persons. A leader is not needed. Ideas are exchanged and people choose to act on them—or not. Groupthink is a very powerful force.”[30] According to her, the formula is simple. She states that an egregious behavior at the hands of a government authority against a presumably innocent person is captured as a video or photo, and the image is posted to a social media application and quickly spreads throughout the region via the Internet.

From social sciences or technological perspectives, there are several studies on this issue. This section does not focus on technological concerns; rather it looks for some social scientific solutions.

4.1 The Power of Social Media

First of all, it is necessary to comprehend the power of social media. As Thompson stated, the purpose of social media is to connect with others and share information. The average person, who is not popular or a well-known individual to use social media, with a worthwhile message or cause can send it to a high-profile individual with a large social media following, and that individual may forward the message to his or her followers, immediately bringing the message or cause to the attention of millions of people throughout the world, who will, in turn, share the message/cause with their friends.

Social media distributes information to all users quickly and efficiently. “YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites now interact with one another; and posting a status update or message to one site automatically updates the other social networking sites. One person or group can instigate a domino effect of events, influencing the attitudes and behaviors of populations worldwide with one tweet or social media status update, which forwards the information to all the other major social media applications.”

“Social media applications are a triple-edged sword that can create addictive information-seeking behaviors that break down social-norm behaviors of its users, encourage users to generate and report information that normally would have been kept private, and ultimately provide users with increased access to information that could be used to manipulate the user’s perception of the world and the user’s environment.”[31]

4.2 Why and How is Social Media Being Used by ISIS?

Terrorists use the Internet and social media as a tool for propaganda via websites, sharing information, psychological warfare, publicity, data mining, fundraising, communication, planning and recruitment.[32]

“Isis is now increasingly fighting an online cyber war, with the use of slick videos, online messages of hate and even an app that all aim to radicalize and create a new generation of cyber jihadists. These modern day tools are helping Isis spread their propaganda and ideology to thousands of online sympathizers across the world. Indeed, the group has actively been using social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook and YouTube to recruit new would be members. This is being done through images and the streaming of violent online viral videos filmed and professionally edited that are targeting young and impressionable people.”

As Awan states, a number of videos depict ISIS as fighters with a ‘moral conscious’ and show them helping protect civilians. Some of these videos also show Isis members visiting injured fighters in hospitals and offering children sweets. Also, much of the Isis literature uses motivational powerful themes which aim to appeal to the youth and at the same time allow groups such as Isis to recruit and maintain its propaganda machine. Furthermore, Isis had released a free to download app which kept users updated with the latest news from the organization.[33]

Photo by Pixabay

“According to Documenting the Virtual Caliphate, an October 2015 report by the Quilliam Foundation, the organization releases, on average, 38 new items per day—20-minute videos, full-length documentaries, photo essays, audio clips, and pamphlets, in languages ranging from Russian to Bengali. The group’s closest peers are not just other terrorist organizations, then, but also the Western brands, marketing firms, and publishing outfits—from PepsiCo to BuzzFeed—who ply the Internet with memes and messages in the hopes of connecting with customers.”[34]

As Awan stated, “the Internet, therefore, is becoming the virtual playground for extremist views to be reinforced and act as an echo chamber.” Thus, this sort of digital propaganda has motivated more than 30,000 people to turn their backs on everything they’ve ever known and journey thousands of miles into dangerous lands, where they’ve been told a paradise awaits.

On the other hand, as Koerner emphasized; more important, it decentralized its media operations, keeping its feeds flush with content made by autonomous production units from West Africa to the Caucasus—a geographical range that illustrates why it is no longer accurate to refer to the group merely as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), a moniker that undersells its current breadth. Each wilayat, or province, now runs its own media office, staffed by camera operators and editors who churn out localized content from Nigeria to Afghanistan.

4.3 Is it Possible to Prevent Social Media Efficiency of ISIS?

“If we’re serious about winning this media game, time is of the essence. To offset some losses in the Middle East, the Islamic State is now moving to strengthen its North African wilayats. The group is already on the verge of turning Libya into its newest stronghold, which is why it’s so important right now to dissuade young men and women around the globe from pledging their futures to the caliphate.” [35]

What ways have been used to decrease the effect of social media efforts of ISIS? Regarding this crucial question, Talbot states: “Internet companies close accounts and delete gory videos; they share information with law enforcement. Government agencies tweet out counter-messages and fund general outreach efforts in Muslim communities. Various NGOs train religious and community leaders in how to rebut ISIS messaging, and they create websites with peaceful interpretations of the Quran.”[36]

According to Koerner, most attempts to neutralize the Islamic State’s media juggernaut have proven inept. He states; that is because the architects of our countermeasures fail to grasp what makes the organisation’s content and distribution method so distinctive. We must admit, however grudgingly, that the Islamic State’s propagandists are now as adept at social media as we are.

What’s highly needed and also challenging is a huge effort to build peer-to-peer interaction online with the potential candidates for terrorist groups. Peer-to-peer work is pretty difficult, because you can’t know whether the people you talk to online are the ones most at risk or are too far gone. This means, there is the risk of not obtaining the aim and a waste of effort.

So, a London think-tank called the Institute for Strategic Dialogue developed a peer-to-peer strategy against extremism. As an example for this strategy, the institute “recently piloted experiments in which it found people at risk of radicalization on Facebook and tried to steer 160 of them away. It was a small test, but it shows what a comprehensive peer-to-peer strategy against extremism could look like.”[37]

4.4 Policy Recommendations towards Social Media

“The Islamic State is an Internet phenomenon as much as a military one. Counteracting it will require better tactics on the battlefield of social media.”[38]

As the legitimate forces of the world, you should not forget that you have a lot of possibilities and advantages that cannot be compared to its if the point is an illegal organization. In that case, you would not be convincing if you say that you are not able to cope. If the social media activity of Isis or another organization cannot be prevented, how to reduce its efficiency must be investigated. So, the governments and NGOs need to take initiative. In order to neutralize the media of a potential or an existing terrorist organization, there is a need for strong social media activity and it is necessary to maintain this activity with determination. On-line training always must go on. It is necessary to be proactive and the reactions never should be delayed. Whatever they are doing, they need to get a lot of response. For example, if they are campaigning, you should organize a counter-campaign which is stronger. You should make more effective counter-propaganda if they make propaganda. The information regarding what happened to the participants, how many young people had to flee, how many young lives have been lost, or how many young people have been disabled should be announced very well.

More specifically, one-on-one engagement is critical. Some efforts are at present, but those are quite inadequate in numbers. So, the attempts of peer-to-peer engagements are needed to be hugely increased in a more systematic and comprehensive manner. The category of each individual, who is discovered as a problematic person, must be determined. Afterwards, the efforts must focus entirely on the individuals who are potentially prone but have not fallen within the scope of phase 3 or phase 4 (explained previously) yet.

5. CONCLUSION

The preceding report examined the sociological process by which an individual adopts radical views, joins an extremist organization, and engages in violence. As it was explained before, to bring long-term solutions to the issue of violent extremism, one should take into account the developmental process pushing an individual toward terrorism. Although a notable effort, in this respect, was represented in extant research, the sociological aspect of the issue has generally been ignored, which indicates the importance of this policy report.

Utilizing the sociological literature, the current study presented a pathway model indicating how an individual comes to adopt radical beliefs and progresses from thinking to action. Our pathway model included four main phases: (1) Experience of Anomie and Strain, (2) Developing Coping Strategies, (3) Choosing Legitimate or Illegitimate Coping, and (4) Engagement with Conformity or Terrorist Activity. Each phase is also impacted by a variety of factors. After presenting the pathway through which an individual engage in terrorism, we then offered effective policies to block the pathway.

Since the requirements of the radical ideology are generally regarded as religious obligations, it is very difficult to deradicalize people after they internalized the radical views. For this reason, our policy efforts have generally focused on the first and second phases of the pathway model. From this point of view, we offered two general policies that should be implemented concurrently towards phase 1 and phase 2 of the pathway model. More specifically, we demonstrated (1) how to prevent individuals’ experiences of anomie and strain and (2) how to help them develop legitimate coping strategies against anomie and strain. Since the social media is the primary ground where individuals encounter the terrorism-justifying ideologies, we examined the issue in a separate part and offered particular policy recommendations toward prevention of harmful impacts of social media with regards to internalization of radical views.

Bibliography

Agnew, Robert. 1992. “Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency.” Criminology 30(1):47-86.

Akers, Ronald L., Marvin D. Krohn, Lonn Lanza Kaduce, and Marcia Rodosevich. 1979. “Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory.” American Sociological Review 44(4): 636-655.

Akers, Ronald L. 1973. Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Atran, Scott. 2016. “The Devoted Actor: Unconditional Commitment and Intractable Conflict across Cultures.” Current Anthropology 57:192-203.

Awan, I. 2017. Cyber-Extremism: Isis and the Power of Social Media, Social Science and Public Policy, Soc (2017) 54:138–149. Accessed 28 Sep 2017.Available at: https://link.springer.com/

Borum, Randy. 2011. “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories.” Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 7-36.

Borum, Randy. 2011. “Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A Review of Conceptual Models and Empirical Research.” Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 37-62.

Borum, Randy. 2011. “Rethinking Radicalization.” Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 1-6.

Cloward, Richard A. and Lloyd E. Ohlin. 1960. Delinquency and Opportunity. New York: Free Press.

Cohen, Albert K. 1955. Delinquent Boys. New York: Free Press.

Conway, M. 2003. What is cyberterrorism? The story so far. Journal of Information Warfare 2(2), 33–42.

Durkheim, E. 1933. The division of labor in society. New York: The Free Press (Originally published, 1893).

Durkheim, Emile. 1951. Suicide. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Gore, Susan. 1985. “Social Support and Styles of Coping with Stress.” Pp. 263-78 in Stress and Health, edited by S. Cohen and S.L. Syme. Orlando, FL: Academic.

Ginges, Jeremy, Scott Atran, Sonya Sachdeva, and Douglas Medin. 2011. “Psychology Out of the Laboratory: The Challenge of Violent Extremism.” American Psychologist 66(6): 507-519.

Hirschi, Travis. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hirschi, Travis. 2004. “Self-Control and Crime.” Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications 2004:537-552.

Hirschi, Travis and M. Gottfredson. 1994. The Generality of Deviance. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Jeannotte, M. Sharon. 2008. Promoting Social Integration—A Brief Examination of Concepts and Issues. Experts Group Meeting July 8-10, 2008 Helsinki, Finland.

Koerner, B. I. 2016. Why ISIS Is Winning the Social Media War, Accessed 25 Sep 2017.Available at : https://www.wired.com/2016/03/isis-winning-social-media-war-heres-beat/

Krueger, Alan B. and Jitka Maleckova. 2003. “Education, Poverty, and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(4): 119-144.

Kruglanski, Arie W., Michele J. Gelfand, Jocelyn J. Belanger, … Rohan Gunaratna. 2014. “The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism.” Advances in Political Psychology 35(1): 69-93.

Kubrin, Charis, Thomas D. Stucky, and Marvin D. Krohn 2009. “Social Learning Theories” Pp137-167. In Researching Theories of Crime and Deviance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lachow, I., & Richardson, C. 2007. Terrorist use of the internet: the real story. JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly, 45, 100–103.

LaFree, Gary and Gary Ackerman. 2009. “The Empirical Study of Terrorism: Social and Legal Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Sciences 5:347-374.

Lazarus, Richard S. and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

Maskaliunaite, Asta. 2015. “Exploring the Theories of Radicalization.” Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal 17(1): 9-26.

McCauley, Clark and Sophia Moskalenko. 2008. “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways toward Terrorism.” Terrorism and Political Violence 20:415-433.

Menaghan, Elizabeth G. 2010. “Stress and Distress in Childhood and Adolescence.” in A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contacts, Theories, and Systems. 2nd ed., edited by T. L. Scheid and T. N. Brown. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Merton, Robert K. 1938. “Social structure and anomie.” American Sociological Review 3(5): 672-682.

Milton, Daniel, Megan Spencer, and Michael Findley. 2013. “Radicalism of the Hopeless: Refugee Flows and Transnational Terrorism.” International Interactions 39:621-645.

Moghaddam, Fathali M. 2005. “The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration.” American Psychologist 60(2): 161-169.

Moghadam, A. 2006. “Suicide terrorism, occupation, and the globalization of martyrdom: A critique of Dying to Win.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 29, 707–729.

Pape, R. A. 2003. “The strategic logic of suicide terrorism.” American Political Science Review 97, 343–361.

Pearlin, Leonard I. 1989. “The Sociological Study of Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30:241-256.

Pearlin, Leonard and Carmi Schooler. 1978. “The Structure of Coping.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:2-21.

Rogers, P. 2006. Personal commentary during climate change: The global security impact. RUSI, London.

Silke, A. 2003. Terrorists, victims and society: Psychological perspectives on terrorism and its consequences. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Sutherland, Edwin H. 1947. Principles of Criminology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Talbot, D. 2015. Fighting ISIS Online, September 30, 2015. Accessed 23 Sep 2017. Available at :https://www.technologyreview.com/s/541801/fighting-isis-online/

Thoits, Peggy A. 1995. “Stress, Coping, and Social Support: Where Are We? What Next?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior extra issue:53-79.

Thompson, R. L. 2011. Radicalization and the Use of Social Media, Journal of Strategic Security, Volume 4, No.4, Winter 2011: Perspectives on Radicalization and Involvement in Terrorism, Article 9, pp. 167-190.

Weimann, G. 2004. US Institute of peace December. Special Report, 119 Accessed 5 Aug 2014.Available at : http://www.usip.org/pubs/specialreports/sr119.html.

Von Hippel, K. 2002. “The roots of terrorism: Probing the myths.” The Political Quarterly, 73, 25–39.

Whine, M. 1999. Cyberspace-a new medium for communication, command, and control by extremists. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

References:

[1] Von Hippel, K. 2002. “The roots of terrorism: Probing the myths.” The Political Quarterly, 73, 25–39.

[2] Borum, Randy. 2011. “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories.” Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 7-36.

[3] Moghadam, A. 2006. “Suicide terrorism, occupation, and the globalization of martyrdom: A critique of Dying to Win.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 29, 707–729.

[4] Pape, R. A. 2003. “The strategic logic of suicide terrorism.” American Political Science Review 97, 343–361.

[5] Rogers, P. 2006. Personal commentary during climate change: The global security impact. RUSI, London.

[6] Silke, A. 2003. Terrorists, victims and society: Psychological perspectives on terrorism and its consequences. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

[7] Borum, Randy. 2011. “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories.” Journal of Strategic Security 4(4): 7-36.

[8] Durkheim, E. 1933. The division of labor in society. New York: The Free Press (Originally published, 1893).

[9] Durkheim, Emile. 1951. Suicide. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

[10] Merton, Robert K. 1938. “Social structure and anomie.” American Sociological Review 3(5): 672-682.

[11] Agnew, Robert. 1992. “Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency.” Criminology 30(1):47-86.

[12] Milton, Daniel, Megan Spencer, and Michael Findley. 2013. “Radicalism of the Hopeless: Refugee Flows and Transnational Terrorism.” International Interactions 39:621-645.

[13] Milton, Daniel, Megan Spencer, and Michael Findley. 2013. “Radicalism of the Hopeless: Refugee Flows and Transnational Terrorism.” International Interactions 39:621-645.

[14] Thoits, Peggy A. 1995. “Stress, Coping, and Social Support: Where Are We? What Next?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior extra issue:53-79.

[15] Lazarus, Richard S. and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

[16] Pearlin, Leonard I. 1989. “The Sociological Study of Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30:241-256.

[17] Pearlin, Leonard and Carmi Schooler. 1978. “The Structure of Coping.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:2-21.

[18] Gore, Susan. 1985. “Social Support and Styles of Coping with Stress.” Pp. 263-78 in Stress and Health, edited by S. Cohen and S.L. Syme. Orlando, FL: Academic.

[19] Menaghan, Elizabeth G. 2010. “Stress and Distress in Childhood and Adolescence.” in A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contacts, Theories, and Systems. 2nd ed., edited by T. L. Scheid and T. N. Brown. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[20] Hirschi, Travis. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[21] Hirschi, Travis. 2004. “Self-Control and Crime.” Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications 2004:537-552.

[22] Hirschi, Travis and M. Gottfredson. 1994. The Generality of Deviance. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

[23] Kruglanski, Arie W., Michele J. Gelfand, Jocelyn J. Belanger, … Rohan Gunaratna. 2014. “The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism.” Advances in Political Psychology 35(1): 69-93.

[24] Kubrin, Charis, Thomas D. Stucky, and Marvin D. Krohn 2009. “Social Learning Theories” Pp137-167. In Researching Theories of Crime and Deviance. New York: Oxford University Press.

[25] Sutherland, Edwin H. 1947. Principles of Criminology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

[26] Akers, Ronald L. 1973. Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach. Belmont: Wadsworth.

[27] Akers, Ronald L., Marvin D. Krohn, Lonn Lanza Kaduce, and Marcia Rodosevich. 1979. “Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory.” American Sociological Review 44(4): 636-655.

[28] See Durkheim, E. 1951.

[29] Jeannotte, M. Sharon. 2008. Promoting Social Integration—A Brief Examination of Concepts and Issues. Experts Group Meeting July 8-10, 2008 Helsinki, Finland.

[30] Thompson, R. L. 2011. Radicalization and the Use of Social Media, Journal of Strategic Security, Volume 4, No.4, Winter 2011: Perspectives on Radicalization and Involvement in Terrorism, Article 9, pp. 167-190.

[31] See Thompson, R. L. 2011.

[32] Awan, I. 2017. Cyber-Extremism: Isis and the Power of Social Media, Social Science and Public Policy, Soc (2017) 54:138–149. Accessed 28 Sep 2017.Available at: https://link.springer.com/

[33] See Awan, I. 2017.

[34] Koerner, B. I. 2016. Why ISIS Is Winning the Social Media War, Accessed 25 Sep 2017.Available at : https://www.wired.com/2016/03/isis-winning-social-media-war-heres-beat/

[35] See Koerner, B. I., 2016.

[36] Talbot, D. 2015. Fighting ISIS Online, September 30, 2015. Accessed 23 Sep 2017. Available at : https://www.technologyreview.com/s/541801/fighting-isis-online/

[37] See Talbot, D. 2015

[38] See Talbot, D. 2015.