|

by Ibrahim Jouhari, Emre Bilgin, Onur Sultan, Furkan Akar, Hasan Suzen OCTOBER 23, 2020| 14 min read |

Background

- On May 8, 2018, the US President Donald Trump, announced the US unilaterally withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) or the Iran nuclear deal as commonly known. Since then, the US Administration has been following a “maximum pressure” policy against Iran. In this regard, the US Administration reimposed all secondary sanctions or sanctions on firms that conduct certain transactions with Iran on November 6, 2018 and in May 2019, it cancelled sanctions exceptions for the trade of Iranian oil.

- The Annex-B of the U.N.S.C. Resolution 2231 that endorsed the JCPOA imposes bans on:

- transfer of arms to or from Iran until October 18, 2020,

- supply of equipment that could be used by Iran to develop nuclear-capable ballistic missiles until October 18, 2023,

- development of ballistic missiles by Iran designed to carry nuclear weapons.

- In line with “maximum pressure policy, on August 14, the UNSC rejected a US draft resolution to extend bans on arms transfer to Iran. The draft got only support of Dominican Republic. Eleven members to include Germany, France and UK abstained whereas China and Russia vetoed it. Following this diplomatic defeat, the US declared it would invoke “snapback” provision of the JCPOA which foresaw reimposition of all sanctions [in effect at the time of the signature of the agreement] back once Iranian government is found in breach. This is found legally dubious as the US has been considered to have lost this ability when it left the agreement by 13 of the 15 UNSC member states. Second, most US Allies are not willing to further pressure Iran for fear that this would further destabilize the already turbulent Middle East.

- In order to maintain maximum pressure, the US has worked on an array of new sanctions against Iran beyond its initiatives in the UN. On September 21, the US President issued Executive Order 13949 that foresees blocking of the US property of any entity that among others “engage in any activity that materially contributes to the supply, sale, or transfer, directly or indirectly, to or from Iran, or for the use in or benefit of Iran, of arms or related materiel, including spare parts”. Then on October 15, The US Treasury Departments punished 18 banks with links to Iran.

- As of 18 October, UN arms embargo on Iran expired.

Analysis

Despite the sanctions, Iran has not ceased to support numerous state and non-state actors across the Middle East like Houthis and Hezbollah. It has disturbed balance through widening religious/ideological divisions in countries like Bahrain and Saudi Arabia and has been supporting sectarian policies in countries like Iraq and Syria. In the US security calculus, an Iran that has set itself free from sanctions will primarily be emboldened to take more decisive action in its disruptive policies and will gradually emerge as a greater risk.

The US calculates Iran will likely upgrade its military capabilities by the acquisition of latest technology fighter jets from China and Russia and bolster its air defenses to protect its nuclear ambitions. Posting the image below, on June 23 the Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tweeted: “If the U.N. Arms Embargo on Iran expires in October, Iran will be able to buy new fighter aircraft like Russia’s SU-30 and China’s J10. With these highly lethal aircraft, Europe and Asia could be in Iran’s crosshairs”

Figure 1 Projected Iranian Aircraft Ranges with New Acquisitions

From the Israeli perspective, Iran lies at the heart of regional risk analyses and threat assessment. Israeli perception of potential threats emanating from Iran runs across four dimensions:

- Iran’s ambitions to become a power possessing nuclear weapons,

- Iranian (c)overt support for terrorist organizations and regional proxy wars;

- Subversive activities of Iran in Arab regimes that view the Iranian regime as a grave threat; and finally

- Ideological and theological threat that emanates from Iran.

Arms embargo on Iran has been a critical element of Israel’s strategic thinking to minimize potential risks and threat from the country. Although the expiration of the arms embargo is unlikely to change the power balance in the region in the short term, Israel thinks that it has to really pull out all the stops and actively lobby to extend arms embargo.

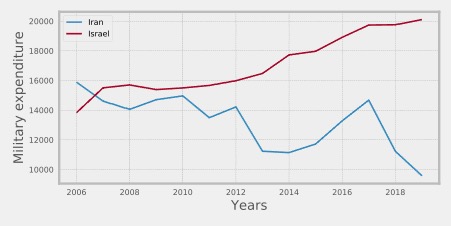

Figure 2. Military expenditure by country, in constant (2018) US$ m., 2006-2019

Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/

The arms embargo implemented since 2007 contributed greatly to the defense policies of Israel, which sees Iran as an arch-foe owing to the aforementioned reasons. If the Figure-1 showing the military expenditures of Israel and Iran between 2006-2019 is examined, it will be clearly seen that the difference between the defense expenditure of the two countries widens in favor of Israel since the implementation of the embargo.

When the military capabilities of both countries are compared, it is evident that Israel’s conventional capabilities are more extensive and superior to those of Iran. In other words, Iran is not in a position to launch a first strike against Israel but can strike as a response, and that would be very destructive for both Israel and the region.

In order to balance Israel in the region and also defend its strategic nuclear sites against air assaults, the first priority for Iran after the dis-embargo will probably be to procure modern aircraft and advanced air defense systems. For that reason, the timing and scope of arms sales to Iran are very important for Israel. By using its close bilateral relationship with Russia and China, Israel will likely seek to hinder them from selling arms to Iran. Reaching the new arms to Hezbollah and Hamas is the other concerning point for Israel because Israel asserts that Iran is the main supplier of weapons to these organizations.

Lebanon will not be directly affected by the lifting of UN arms sanctions on Iran. Lebanon’s armed forces (LAF) rely almost exclusively on US arms aid and imports. However, Hezbollah, an armed Lebanese militia, is fully funded and equipped by Iran. The lifting of the sanctions will ease the arms transfer between this state and non-state actor only to an extent, as the two main obstructions to these transfers, namely the US and Israel, have been and would probably still be fully active. Indeed, Israel has been regularly bombing Iranian arms caches or convoys en route to Lebanon, while the US have been working behind the scenes with sanctions and dismantling of arms smuggling networks. Indeed, these efforts will not stop or be affected by the lifting of the UN arms embargo, but they might even be strengthened!

There have been recurrent domestic calls for the Lebanese government to start buying or receiving air defense and other sophisticated weapon systems from Iran. Pro-western political parties in Lebanon have so far flatly refused such calls, citing the UN arms embargo as the main hurdle. Now that the embargo has been lifted, these calls, especially pushed by Hezbollah and its allies will increase and the pressure on the Lebanese government to start importing weapons from Iran will increase in an unprecedented way, threatening the current US aid to the Lebanese Armed Forces. Indeed, the US has always been adamant that any Iranian or Russian arms imports to LAF will be met with an immediate cessation of the 200$ million-plus yearly US aid to LAF.

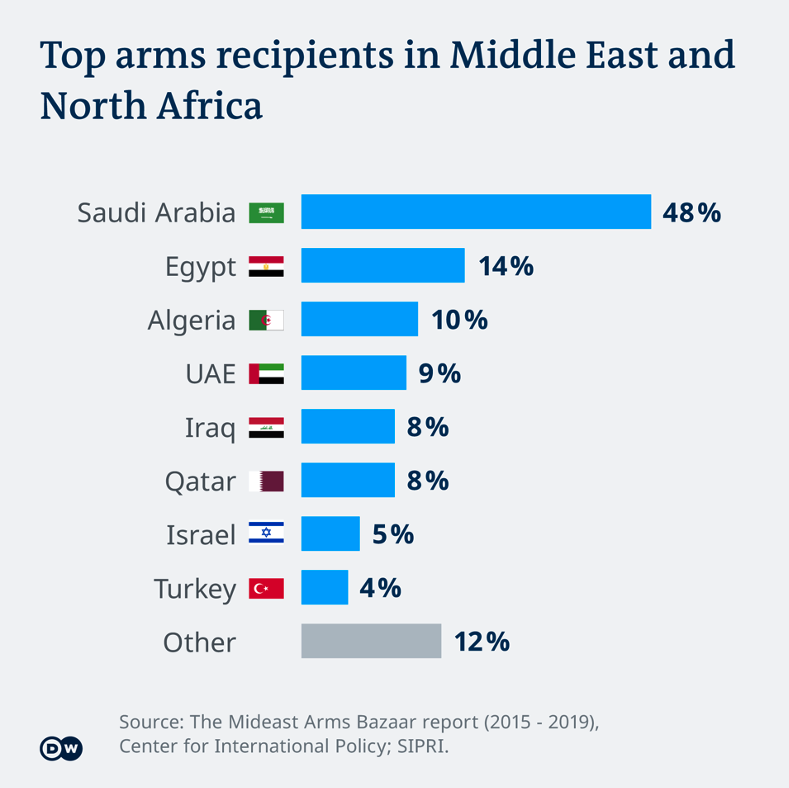

The lifting of the arms embargo will unleash another arms race in the Gulf. Indeed, the six Gulf countries were fully against the lifting of the UN arms embargo and lobbied hard to stop it.

Now that the embargo has been lifted, the Gulf Countries, especially the KSA and the UAE, will ramp up their already significant arms import from the West. Indeed, with every modern weapon system, Iran buys (although with its current weak economy, these will be limited, unless Russia or maybe China agree to open lines of credit to Iran to buy weapons) the Gulf countries will acquire even more modern and expensive weapon systems from the west, mainly the US to balance the perceived threat.

This is already evident in the efforts of the UAE and Qatar to buy F-35s, the fifth-generation fighter jet from the US. This trend will continue and will be amplified, especially if President Trump is re-elected, which would lead to another White House press conference in which the US would announce the exporting of even more weapons to the KSA and the rest of the GCC, to counter the threat of a better armed Iran.

Meanwhile, once the election dust settles in the US, it is expected that the US will not sit idly, allowing Iran to buy the weapons it needs or sell what it manufactures. On the contrary, the US will follow the same modus operandi it used after withdrawing from the JCPOA: threatening any western, and even Chinese or Russian companies that sought to do business in Iran with its own harsh sanctions, resulting in very few European companies setting up business relations with Iran. Similarly, the US with the help of its GCC allies will be very closely observing Iran, tracking any arms companies that are trying to work with Iran, making sure to enforce the sanctions regime in another format.

Meanwhile, once the election dust settles in the US, it is expected that the US will not sit idly, allowing Iran to buy the weapons it needs or sell what it manufactures. On the contrary, the US will follow the same modus operandi it used after withdrawing from the JCPOA: threatening any western, and even Chinese or Russian companies that sought to do business in Iran with its own harsh sanctions, resulting in very few European companies setting up business relations with Iran. Similarly, the US with the help of its GCC allies will be very closely observing Iran, tracking any arms companies that are trying to work with Iran, making sure to enforce the sanctions regime in another format.

The war in Yemen is by many framed as a proxy war pitting Iran-supported Houthis against government forces supported by the KSA. In the last 6+ years of the war, Iran has been well documented to support Houthis by smuggled weapons and by increasing their war-making capacity through Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) or Iranian proxy, Hezbollah. To showcase the relationship between the two, on both November 25, 2019, and February 9, 2020, the United States seized arms and related materiel in “international waters assumed to be destined for Yemen” and arms were assessed to be “evidently of Iranian origin” by Secretary General’s Report on Implementation of the UNSCR 2231. On the other hand, in September 2019, Houthis claimed to have conducted the attacks on the Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq and Hurais while Iranians denied having made the attacks. These two events show how Iran supports Yemen by smuggling weapons to the group whereas the latter is ready to carry the brunt of such an attack, trying to shift the direction of repercussions of the event on itself and Yemenis.

The Houthis are non-state actors. Although their presence in diplomatic efforts initiated by UN Special Envoy adds more legitimacy to their de facto rule in the north of Yemen, they are not yet accepted as legitimate representatives of Yemen. As such, Iran cannot directly transfer arms to Houthis. So, termination of the sanctions on Iran will not change the modus operandi of the country. But a bold Iran that smuggles weapons and mobilizes support for Houthis despite sanctions will likely have more means and opportunities to extend that support in their absence. In the mid-term, in case Iran manages to acquire more sophisticated arms and weapons system, it will transfer some of older systems to Houthis either by sea or through an existing route near Oman border.

A geostrategic price for encouraging Moscow and Tehran to form a strategic alliance to oppose the Western interests in the Middle East is to apply pressure on Iran. To understand deeply the nature of this strategic alliance, it is worth diving deeply in economic relations, military cooperation, and common threat perceptions. Collaboration between Iran and Russia in the political, economic, and military arenas has increased substantially in recent years. The supporting position of Russia in passing the JCPOA facilitated stronger economic relations between Iran and Russia. While Russia has little interest in buying Iran’s key oil exports, Russian companies have explored opportunities in Iran’s oil and energy sector. Russia doubled its deal to develop nuclear power capability in Iran in July 2016. In addition, by means of multilateral agreements, Iran and Russia are enhancing economic relations. In the Middle East, Russians are also securing their own financial interests. To this end, the Russians are keen to join the Instrument to Support Trade Exchanges (INSTEX), a new financial system set up initially by the United Kingdom, France and Germany to sustain trade with Iran and to circumvent the sanctions imposed by the United States.

Turning to military cooperation, given the tense past between them, it is at an unprecedented stage. Historically, Russia has been one of Iran’s main suppliers of arms. Particularly, the war in Syria causes a significant potential for a long-lasting alliance between Russia and Iran. Further, Russia and Iran are the top military backers of the efforts of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad to win the nine-year conflict in the region. After the approval of the JCPOA, the renewal of the S-300 missile defense system contract signalled a strengthening of ties between Russia and Iran. Further, it is crystal clear that since the beginning of its participation in the Syrian Civil War in 2015, Moscow’s closer ties with Iran have helped cement Russia’s role in the Middle East.

Common threat perception is a pillar of Iranian-Russian security convergence. In essence, the crisis in Ukraine persuaded Moscow to strengthen its relations with the states of the Middle East in order to mitigate the implications of international isolation. That’s why the Russian stance on the US and UN sanctions and embargoes against Iran is always clear. In every bilateral and multilateral platform, Russia highlights the unacceptability and the illegitimate nature of unilateral restrictive measures aimed at blocking Iran’s foreign economic ties. Therefore, it is not surprising that on September 24, Lavrov declared the intention of Moscow to trade with Tehran once a United Nations weapons embargo expires next month. He also expressed hope that other countries cooperating with Iran will take a principled stance and be motivated by their national interests rather than by the need to listen to orders from abroad.

For the European Union, the expiration of UN sanctions has two significant implications. First, this will provide some fresh air to the deal that is in the emergency room due to the US withdrawal and sanctions crippling Iran’s economy. The Iranian Banks cannot use the SWIFT system due to the US sanctions. The EU devised INSTEX mechanism to shelter European companies dealing with Iran against US punishment. However, INSTEX couldn’t become a viable alternative to the SWIFT.

Second, the US could unilaterally exert influence upon neither its European Allies nor the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The Europeans dismissed the idea that the US imposition of sanctions should trigger the snapback mechanism since the US withdrew the agreement. The EU struggles to keep the international institutions and multilateralism up and running while the US Presidency continuously strives to undermine them. Therefore, this is a (temporary) success of the Union and other countries against the US unilateralism and `maximum pressure` policy.

Strategic Foresight

Based on the analyses above, it is highly likely that:

Russia and Iran will continue to cooperate, despite gaps in their Middle East strategies, due to mutual opposition to NATO’s expansion into the Caucuses and the US-led plan for regime change in Syria. It can be anticipated that in the mid-term, a deeper relationship between Iran and Russia would evolve over common challenges to stability, such as sanctions which provide “justified reason” for Moscow to deepen economic ties with Tehran; and terrorism conducted by Salafi jihadist groups like ISIS, radical Sunni insurgents, and Wahhabi extremists and that pose a threat to internal stability in Syria, Iran, and Russia, respectively.

Iran will upgrade its armed forces with new generation air, ground and naval vessels and weapon systems and A2AD capabilities through acquisition from Russia and China.

The US and Israel will use their influence in both China and Russia to limit quantity and technological level of the arms to be made available to Iran in case the latter demands.

In the eventuality that Iran upgrades its armed forces with new generation weapons systems, this will trigger new arms sales to the Gulf countries mainly from the US.

The Lebanese government will face political challenges based on calls for the acquisition of Iran-made weapons and necessity to rule those out to maintain US support.

Iran will increase its support to the Houthis in Yemen although sticking to its pre-October 18 methods.

The US position vis-à-vis JCPOA and Iran will depend on results of the incoming US elections. Preserving JCPOA despite the US President is becoming an experiment for the Union to prove its global actorness and credibility as the guardian of multilateralism. On the other hand, what will happen if Joe Biden, who was the Vice-President of the US when the deal was signed, is elected, time will tell us.

MENA Task Force Brief

MENA Task Force Brief