Daesh is about to lose the whole territory it holds in Syria and Iraq once as big as the UK. The Salafi jihadist organization, ruling over 6 million population with an army of 30.000 in 2015, had benefited from sectarian and ethnic tensions and imposed its ideology to recruit and attract more than 40.000 foreign terrorist fighters from across the globe. The question that keeps busy most European capitals currently is;

“What awaits Europe after Daesh loses all territory it controls?”

The answer to this question will help show the next steps to neutralize its negative effects. Within the scope of this study, the trends shaping the flow of events have been studied to prescribe four future scenarios. Accordingly, the first scenario foresees that Daesh will revert gradually to terrorism from its proto-statehood. The second foresees that as long as it holds a social base, Daesh will survive and pose a real threat for Europe in the foreseeable future though in decreasing intensity. The third finds its transformation to a “Virtual Caliphate” a low probability. The fourth and last scenario finds the possibility of its replication in one of its eight provinces a small chance. At the end of each scenario policy recommendations have been made to reverse those trends.

1. Introduction

Daesh is about to lose its total territorial gains in Syria and Iraq. On December 9, 2017, Iraqi PM Abadi declared victory over Daesh after three years of struggle whereby Iraq had lost one-third of its terrain, to include strategical cities like Mosul and Tikrit.[1] In Syria on the other hand, Daesh is currently giving a vital struggle along eastern and western flanks of Euphrates river with its some remaining 3.000 fighters against coalitions headed by USA and Russia.[2]

Based on this advance, both international community and the countries affected by Daesh have been preparing to celebrate the disappearance of black dots symbolizing it from maps. Those on the field are well aware that this means just a transformation rather than extinction. Daesh or its decedents -whatever name or form they shall take- will continue to be operational both physically and as a potential to create further security challenges for Europe. As pertains to the primary audience of this study, the most crucial question of this study is: what exactly awaits Europe in the post-Daesh world?

This question is essential in that countering and defeating a threat requires first understanding its true nature and anticipating its next moves based on this insight. This study aims at serving to fulfill these two tasks: understanding and anticipating. The latter is in simplest terms the art of connecting the dots. In this regard, it is essential first to identify the trends that have been definitive in shaping the chain of past events to make projections about the future ones. As those trends do shape flow of events, they will equally create new dots along the line if not reversed or redirected.

Within the context of the study, I used NATO’s multiple futures methodology. I envisaged four different futures to include most likely and most dangerous ones based on the trends so far. At the end of each future, I made policy recommendations, an attempt to change futures through stopping or reversing those trends. The methodology is didactic in that it establishes the causal link between the phenomena witnessed and offers opportunities to break that link or preempt repetition of past failures.

2. Understanding Daesh

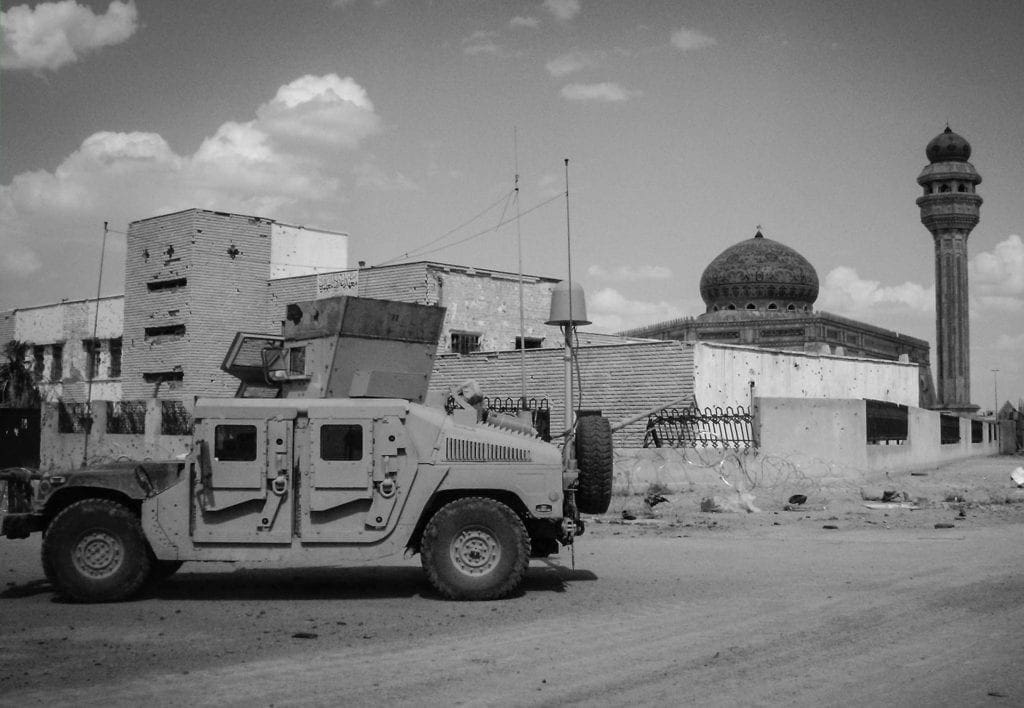

Daesh is a Salafi-jihadist terrorist organization of which history goes back to “Jama’at al-Tawhid wa’l Jihad” in 1999. It became AQI (Al-Qaeda in Iraq) in 2004 under the leadership of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, where it joined insurgency against American-led forces during the invasion. At the beginning of 2006, the organization merged with other Sunni groups under the name Mujahideen Shura Council. Towards the end of the same year, it merged with six out of 31 Sunni tribes under the name Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). During the announcement of this self-proclaimed state, a masked fighter would say: “We swear by God to do our utmost to free our prisoners and to rid Sunnis from the oppression of the rejectionists (Shi’ite Muslims) and the crusader occupiers…” [3] As would be understood from this declaration, the debaathification process which severely erased the Sunnite population from political landscape of Iraq and Maliki government’s discriminating and harsh treatments towards the polity caused popular support for ISI especially in Al-Anbar, Nineveh, Kirkuk, Salah-ad Din, and partly in Babil, Diyala, and Baghdad.[4] In April 2013, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, taking into account the void of credible powers in the theater and the deadlock over interference by major powers, overtly stated that ISI would extend its operations to Syria. He changed the name of the organization as ISIS or the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham. Then on June 2014, Baghdadi declared his so-called “caliphate.” So Daesh and its predecessor first made a claim on statehood in 2006 and on caliphate or religious and political rule on all Muslims in 2014.

The latter claim has several inherent connotations. First with the declaration of caliphate Baghdadi positioned himself above all Muslims to include other Salafi-jihadist organizations like Al Qaeda. This assertion heralded coming fights among such groups for supremacy. As there can be one only one caliph and as those not pledging allegiance would be accepted as apostates a series of mutual excommunications and fights for superiority ensued. Second, this proclamation positioned the so-called “caliphate” or “Islamic State” as the only place on earth where the “purest” Islam -as Daesh perceives- would be exercised. The Salafi ideology targets to create conditions and live the Islam in the form it existed during Prophet Muhammad’s time. Daesh skillfully used this image to lure more fighters to its ranks. Third, with this proclamation, Daesh unilaterally put itself in a position where it could speak in the name of Islam, define what Islam is and offer necessary interpretations.[5]

Especially this last part has many problems. Lacking own cadre of scholars, Daesh in reality taps into Salafi-jihadist ideology and selectively borrows religious texts with no contextuality in ends justify means fashion.

Photo by Pixabay

Basing its ideology or interpretations on narrow, selective reading of Quran and Prophet’s words, Daesh scholars dismiss the practice based on interpretation of Muslim scholars in the past 14 centuries. In their messianic understanding of state and religion, an Islamic state should be created to prepare the grounds for the expected “Mahdi” to bring order.[6] To form that state and attain superiority over other Salafi-jihadist terror organizations, Daesh uses extreme violence both towards internal and external opposers and sanction systematic criminal acts if it will result in more recruitment and cohesion. One good example is the systematic abduction, sale and raping of Yazidi girls and women well documented by media.[7] Yet this should not create an impression that it is only non-Muslims that got its share from Daesh violence. As Obama states, the vast majority of Daesh victims are the Muslims themselves.[8]

Daesh and the others of its ilk are worlds apart when it comes to their indigenous worldviews and methods to attain political aims. Its claim on statehood and then caliphate, its securitization against other Salafi-jihadist organizations and struggle for supremacy indicate that Daesh prioritizes “near threat” over “far threat.” Embedded well in Salafi-jihadist terminology, the far threat refers to the West in general and the US more specifically. According to their ideology, the West supports and keeps in power corrupt, authoritarian and repressive regimes in the Muslim world, which constitute the “near threat.” This collaboration aims at preventing a borderless “dar-al Islam,” a country in line with their ideal state model. For them to prevent such meddling, the West’s will to interfere in Muslim World and dar-al Islam should be hurt by inflicting damages to their interests or where it hurts most. In the post 9/11 era, those networks became a staple in daily media coverage in West based on the violence they perpetrated with no visible discrimination of targets.[9]

This superfluous coverage of the jihadist terror had opposite effects in Western and Eastern Worlds. In the West, those were conflated -this continues till today to an extent- to the real reactions of Islamic World, an overestimation of such groups to the detriment of the latter. In reality, such networks are very marginal and do not represent Islam in neither numbers nor concept. Yet their deeds caused fear and perception of threat in the West towards Islam and Muslims. It further resulted in “polarisation” of the Muslims in Europe or a perception towards them as “the other”. The result has been an identity crisis for many Muslims in Europe.

In the Muslim World too, the acts of Salafi-jihadist terrorist organizations proved to be counterproductive. As can be followed from its precedents in the examples of Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in Algeria, their operations diminished their support base and showed the voidness of their political objectives together with their teachings. Due to lack of political, social and territorial base, such organizations’ nebulous agenda had no eminence or creativity to attract multitudes except for places like Iraq where the effects of post-invasion havoc dovetailed with sectarian persecution. Still, thanks to wide media coverage for their atrocities they were able to attain a level of recognition far beyond their reach.[10]

Based on those lessons learned, Daesh followed a different strategy, giving priority to the near threat and healing all those deficiencies mentioned above. In its statehood initiative, Baghdadi’s first move was to present himself as the defender of the Sunnite population oppressed by Shiite government in Iraq. This assertion provided a social base, territorial depth, political power and steady supply of fighters not sharing the same extremist ideology.[†] This proto-state proved instrumental in building up the romantic image of an Islamic state answering for the needs of jihadi candidates from all walks of life from the region and the world. In the post-caliphate era, Daesh constantly posed itself as land for pious Muslims willing to live according to their beliefs in serenity, away from polarisation, oppression and tyranny of the infidels (!). In line with its slogan “Baqiyah wa-Tatamaddad” (settle and expand), Daesh claimed to be victorious all the time and that this war required all Muslims to be a part of such success story by moving to Daesh soil and make jihad. The land of Daesh was resplendent, and there were pure women for jihadis as wives who would readily help constitute the main tenets of this so-called Islamic state by supporting their men and raising their kids as new jihadis.[11] In the run-up to 2016, remarkable victories above all in Mosul created great allure for Muslims and converts in Europe and across the globe. Its propaganda and what it offers was amplified through media effect showing new atrocities committed every coming day. Online propaganda was not solely enough to radicalize or find recruits. Especially the women joining Daesh from foreign lands engaged those back home to seduce them to make the trip, “hijrah” to Daeshland.

At its height in September 2014, Daesh was able to control a land of the same size as the UK with about 210.000 square kms.[12] This corresponded to one-third of Syria and Iraq combined. Daesh also started to spread beyond borders to states in MENA region where the state was either repressive or was it weak. Those states included Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Afghanistan, Nigeria. [13] The terrorist network was able to recruit more than 42 000 from more that 120 countries between 2011 and 2016. About 5.000 of those came from Europe.[14] France alone had about 1910 FTFs corresponding about 40%of the total from EU and ranked 5th among those states who had most FTFs reaching Syria and Iraq. Departures peaked in 2015 and stemmed in 2016 constantly decreasing in the period in-between. According to estimates, so far 30 % of the FTFs returned to their homes in Europe mostly comprised of women and children. The remaining have either been killed in the conflict, hide in somewhere trying to decide where to go or escaped to third countries.[15]

3. Multiple Futures

a. Will Daesh Perish?

Daesh is the latest mutant in the evolutionary line of Salafi-jihadism. The reasons that gave rise to its existence were put concisely by the former US President Obama saying: “ISIL is a direct outgrowth of Al-Qaeda in Iraq that grew out of our invasion, which is an example of unintended consequences.”[16] In the wake of invasion in 2003, the destruction of whole statecraft and disbanding of the security forces left Iraq bereft of the experienced / skilled human capital to build a nation of unity. The inability of US to justify the invasion and its effects in the restructuring of the new state privileging Shiites as final arbiters in the fate of the state provided ammunition to the jihadi narratives. Also, the unchecked oppression of the Sunnite population during al-Maliki’s ten-year rule between 2006-2016 and his close cooperation with the Iranian government created an estrangement of the Sunnites in the country. Under these unique conditions, Daesh made collaboration with former Baathist officers and Sunnite tribes in its fight against the West and its collaborators(!), the Shiite dominated central government. Daesh used those unique conditions to create its proto-state in Iraq. When conditions ripened in the civil war in Syria, Daesh took its chances for expansion into Syria.

As of today, Daesh’s self-proclaimed caliphate is on the brink of extinction. Daesh has never had a social base in Syria. So, this loss of land means losing almost total footprint in Syria. For Iraq on the other hand, Daesh’s extreme violence can be said to have estranged the once supporter tribes in Iraq. However, it is not possible to mention a total loss of social base. Because the disillusionment in the institution of politics, the politicians and Abadi rule is not gone. Sectarian hostility, corruption and lack of transparency are diminishing the security for Iraqi people and endangering national unity. In the haste to defeat Daesh, Iraqi government welcomed unorthodox methods to include employment of Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) which was formed from predominantly Shia components. PMFs are not under total control of the Iraqi state. Still, the state will be held accountable for the atrocities PMFs committed against Sunnites during the insurgency. There are many reports documenting killing, torturing, kidnapping and extorting civilians by PMF. [17]

What’s more, on September 25, 2017, Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) made a referendum with 72 % turnout. By 92% the voters opted for secession. To complicate the issue, by holding the referendum in contested territories like Kirkuk, Barzani attempted to legitimise Kurdish hold on such multi-ethnic entities. To attain demographic dominance, Peshmerga forces had forcefully displaced natives and destroyed their homes in those contested territories after their reclaim from Daesh.[18] This also eroded the trust of the Sunnites towards the state.

Based on all those reasons above, Daesh is expected to continue to exist as a terrorist organization in Iraq after losing its proto-state. However, it will aspire to transform into an insurgent group by holding territory, and imposing order.[19] To attain this goal, it will benefit from ethnic and sectarian competition in the weak presence of state. It will try to play the role of the state by first providing security then services. This will result in gradual gains regarding popular support. Within the same context, Daesh will try to carve itself a role especially in the probable conflicts where various sectarian groups will try to attain control over disputed and liberated areas. It will be instrumental in the reconstruction of war-torn cities to win hearts. This is the most likely future. In addition, the brutality of Daesh has alienated its potential supporters, the Sunnite tribes. Daesh may try to change name and appearance to appeal to the same audience, putting difference between its current and former self to regain the trust of the local Sunnite tribes.

Policy Recommendations (a)

Joel Migdal defines the ideal state as “an organization, composed of numerous agencies led and coordinated by the state’s leadership (executive authority) that has the ability or authority to make and implement the binding rules for all the people as well as the parameters of rule making for other social organizations in a given territory, using force if necessary to have its way.”[20] It is clear that Central Iraqi government is far from this definition. It does not have total control over the use of force. To win the war against Daesh, it has cracked the door open to the contrary implementations like PMFs. Also by accepting Iranian help, it has become more prone to its effects which especially hurts its image.

It is regrettable that despite having made some progress over the reconstruction of security forces, Haider al-Abadi has not been able to make much progress in Iraq. He has found himself in many cases within the intra-Shiite rivalry. Polls about the parliamentary elections to be held on April 2018 shows that Haider al-Abadi will be elected for a second term. Mr.al-Abadi should be supported by EU and Member states against the negative influence of cleric Muqtada al-Sadr and pro-Iranian former PM Nouri al-Maliki by clear support in definition and implementation of the reforms required to reinforce and develop the institutional structure of the statecraft. To create a mechanism for such, a special relation should be created between Iraq and EU.

It should be noted that no insurgent or separatist organization can exist in an area for a long time if it has no social base. They do feed on ethnic, religious and sectarian competition or weak state institutions to survive. Mr. Abadi should focus on attaining a new social contract among the different ethnicities in the country to promote peace. In this regard, inclusive policies should be put in place, and the Sunnites should have more say in the governance. He should pay particular attention to fight against corruption and attain national cohesion and confidence. He should heed more the institutionalisation of the state and its full functioning.

EU has great experience and mechanisms to help Iraq make haedway in this direction. The lately formed “The European Union Advisory Mission”, which came about 2,5 years after Defence Capacity Building (DCB) package to Iraq by NATO, is a late step in the right direction. The work of this newly formed mission should be tailored to Iraqi needs and the remedies it recommends should be holistic and tied to carrots. Piecemeal solutions or small attempts do not yield result. The functional systems/structures within the state should be rehabilitated based on EU or Member State experience. Success in reformation should be rewarded.

The problems Iraq face do not emanate solely from within its borders. Iraq should be supported in its reformative actions by also bringing other regional actors to the table, especially Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Jordan. All those countries have been important actors in the struggle against Daesh and has potential to affect or contribute to the security conditions in Iraq. Clear carrots and sticks should be defined for positive or negative actions.

The same countries mentioned above and Iraqi Security Forces have gathered great intelligence on Daesh and the actors on the ground. Daesh keeps neat record in areas under its control. EU intelligence and Situation Centre (IntCen) should seek ways to share intelligence of mutual interest with Iraq and try to gain as much as possible to help prevent terrorism within its own borders.

b. Will Daesh remain as a security challenge for Europe in the next decade?

European leaders have been apprehensive about the returnee foreign terrorist fighters (FTF) especially since 2015. It is a known fact that Daesh has been sending FTFs with European origins to their homelands to conduct suicide bombings or to set up cells to recruit new adherent. As such, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a Belgian Daesh ringleader was sent to his home country Belgium to organize and carry out the deadliest suicide attack in France to result in the death of about 300 innocent civilians.[21]

Photo by Pixabay

At least six of the perpetrators of Paris attacks were FTFs that had entered Europe in late summer of 2015. In the case of Brussels bombings which included the bombing of Brussels airport and a metro station on 22 March 2016, three of the perpetrators were FTFs in the same manner. As Daesh started to get military setbacks on the field starting from the beginning of 2017, this apprehension took a different turn in two ways. First, a new wave of Daesh attacks were feared to take place in Europe. Because, as it was the case formerly, Daesh media campaign was based upon attacks in Europe in case of military setbacks to distract attention. Second, it was feared that after those losses, escapee or disillusioned jihadis would return Europe after it became clear that the caliphate’s days were numbered. For both reasons FTFs posed a risk and thus caused great unrest.

According to Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), so far about 30 percent of the FTFs have returned to Europe. RAN experts claim that there will not be so many fighters coming directly from the so-called caliphate. Instead of a “mass exodus” women and children will return to their old neighborhoods.[22]

Among many, some of the reasons for this low return rate can be cited as:

- Deaths of FTFs on the battlefield

- Will to fight until the last moment

- Being stuck in Syria, Iraq and Turkey and/or indecision where to go in the meantime.

- Self-transportation to other Daesh provinces (wilayats) or third countries.

Peter Neumann, a well-known expert on radicalization and director for International Center for the Study for Radicalization, says:” I’ve been saying for a long time that there won’t be a ‘flood’ of returnees, rather a steady trickle, and that’s what we are seeing. Many of them are stuck in the Turkish border areas, where they are contemplating their next move.”[23] Amidst this mood of optimism, a news by BBC showed that about 3.500 Daesh fighters to include their families were allowed to safely evacuate Raqqa after a deal was struck with Kurdish forces. Initially unwilling to speak about the issue, the coalition spokesperson admitted the deal. According to this substantiated news, Daesh militants were given a pass to freedom from Raqqa to pass to first Idlib and then spill over to different lands through different routes. [24]

So the question is, what should one make out of the low return rate of FTFs? Is it good or bad news? Can Europe be content if a battle-hardened European citizen who has fought within the ranks of Daesh passes from Syria or Iraq to Egypt? Or should Europe still accept the same person as a threat based on his potential to transport himself to Europe and further commit terrorist acts? The general tendency among European policymakers has so far been observed as the former. They underestimate the potential of threats that did not revert to Europe directly.

FTF is only one side of the multifaceted problem. A former British intelligence officer and an important counter-terrorism expert, Richard Barrett on the other hand tries to draw the attention of the audience to another point. In the latest report he wrote: “At least initially, those who have traveled to Syria are less likely to see themselves as domestic terrorists than those IS sympathizers who have stayed at home. They generally appear to have had a stronger desire to join something new rather than destroy something old. As a result, returnees have, so far, proved a more manageable problem than initially anticipated.”[25] It is arguable that those already radicalized but never made the journey to the “caliphate” pose a more significant threat to Europe.

Another important dimension to be taken into account is the causes pushing them to radicalize and become an FTF in the first place. A deep insight into this may open up windows to sound recommendations. To be motivated by such ideology and make the journey to war-torn countries there should be some strong push and pull factors. In a recent publication by RAN, they have been listed as such:

There are many reasons why recruits are attracted to this destructive ideology and motivated to join. For some it offers excitement and status, looting opportunities, wages, housing, and the option to keep women as slaves; for others, it is an opportunity to offer humanitarian support. For some, it offers an escape from their ordinary, depressing and problem-filled lives. Others seek belonging, a sense of purpose and a higher calling. It can offer excitement and action, or strict rules on how to live within a clear moral framework. Some are recruited from within their families and friendship circles. Using grooming techniques, Daesh recruiters identify individual psychological weaknesses and skillfully exploit these through online and offline techniques.[26]

Fawaz Gerges asserts that Daesh “appeals to disaffected and disadvantaged Sunni youths around the world, who are often dealing with issues concerning their identities.”[27] Afua Hirsch, a freelance journalist, writing in the Guardian, finds the root cause of extremism as “alienation.” She further continues saying:

They (young Muslims in Britain) are British; they were born here, and don’t know life anywhere else. But they are sharply aware that mainstream society has not quite grasped this. If you are not white in the UK, people constantly ask you where you are from. With a father who was born here and a mother who moved here when she was 11, I have tried a variety of answers to this question: “south London” rarely suffices. People want an explanation; perhaps an arrival date, a stamp in the passport.[28]

Then she quotes one interviewee, Kash Choudhary who says: “Minority British people have developed their own labelling, “Black British” or “British Muslim”, for instance, or in some cases, simply opting for the non-white country in their heritage to explain their identity – I’ve frequently ended up describing myself as “Ghanaian”, despite having visited the country for the first time when I was 15.”[29]

Here comes the main question. Among so many feeling themselves deprived and unfairly treated why some remain on the ground whereas some others join the ranks of terrorist organizations. Using an analogy of climbing a narrowing staircase, Moghaddam opines:

“These individuals believe they have no effective voice in society, are encouraged by leaders to displace aggression onto out-groups, and become socialized to see terrorist organizations as legitimate and out-group members as evil. The current policy of focusing on individuals already at the top of the staircase brings only short-term gains. The best long-term policy against terrorism is prevention, which is made possible by nourishing contextualized democracy on the ground floor.

All in all, it is arguable that Daesh has successfully mobilized those alienated, disadvantaged and polarised youth with a promise of a land that they would rebuild identity or enjoy what they lacked. The validity of the promise had a deadline until the military successes stalled and Daesh started to lose territory. Then the numbers of the FTFs to join its ranks stalled in a parallel way. The statistics of FTFs by dates they joined Daesh reflects a peak in 2015, after Mosul, and a low point 2016.[30]

Despite its claim of “caliphate” for a period, Daesh is a transnational terrorist organization with Salafi-jihadist ideology. The developments following its total loss of terrain will be definitive in shaping its future policies and strategies. Based on its modus operandi so far it can be fathomed that to sustain the link between itself and its adherents, Daesh will try to compensate its losses on the ground by attacks in Europe and interpretative narratives justifying those losses. To accomplish that it will have to depend on its sleeping cells in those countries, returnee jihadis or will it have to order some of its remaining militants to pass to Europe by illegal ways. Daesh will evaluate all those elements to keep the momentum of recruitment alive. This recruitment does not mean a travel to Iraq or Syria. But to gain adherents ready to execute its orders. For that reason, it will continue to radicalize the European Muslims and converts through its members in Europe and online propaganda to be able to use them for such attacks and spread its ideology. Some of those aforementioned possibilities should be looked carefully into.

Policy Recommendations (b)

The geography populated by Muslim countries has been witness to interference by global and regional power competition for hegemony and access to natural resources. In the era between two world wars England and France, in post-WWII era, US and USSR have been active in shaping the political, social and economical landscape. In the post-Cold War era the problems have not ceased to exist.

Photo by Pixabay

The last US invasion of Iraq and the selective response of the West in the face of Arab Spring have produced great distaste and sentiment of injustice among Muslims. However, this does not mean that Muslim World agrees and finds the use of terror by transnational jihadi networks legitimate. On the contrary, they do feel angry because those terrorists are simply conflated with “Muslims” or “Sunnite Muslims” more precisely. They do also feel the frustration of not being able to explain this to the average man walking on the streets of Western capitals and them being polarised / behaved as alien or the other in the society they live in.

Europe and the member states should heal this identity and polarization problem of their Muslim citizens. There is need to differentiate between a terrorist organization and a religion. This distiction should be made at all levels from politicians to the general public and this should be meant rather than said. For that more effort should be invested to understand Islam and the frustrations lived by Muslims within Europe.

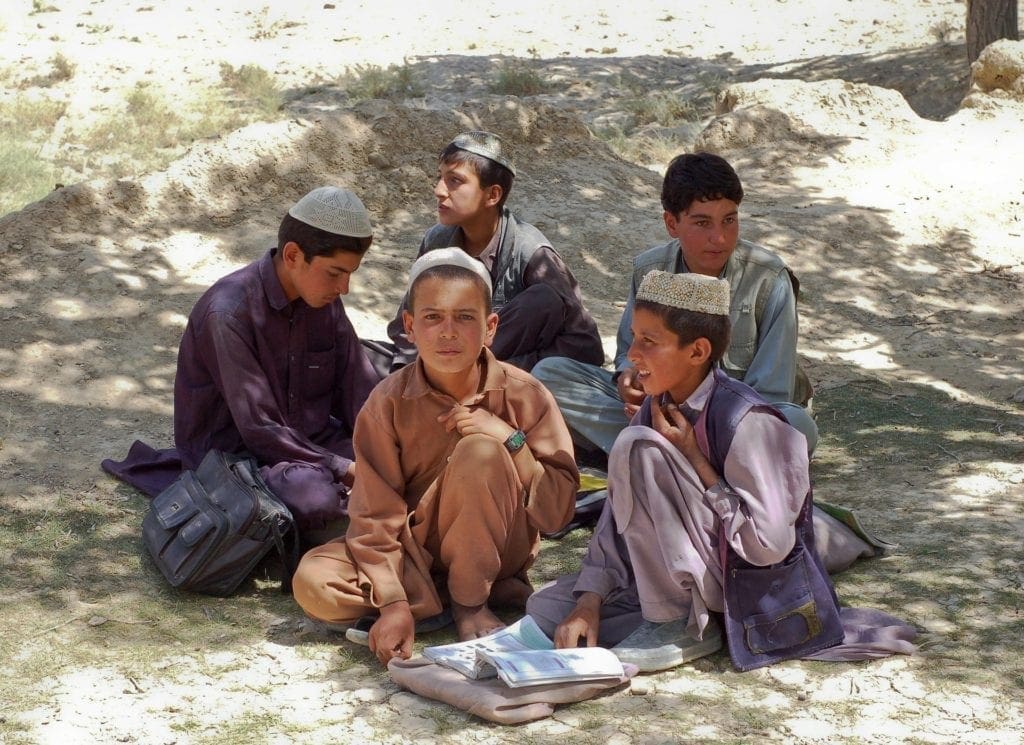

There has not been a sole profile for those joining Daesh. However, low educational and socio-economical conditions of Muslims has been two important factors in joining Daesh. Both common sense and studies tell us better education result in better jobs and better sociological status. Europe should pay special attention to “education” to integrate their Muslim citizens and heal prejudice towards them. Better educated EU citizens will add more value and rightly guide posterities on the threat of radicalization.

Photo by Pixabay

A considerable number of Muslims living within EU borders have internalized the values represented by EU like democracy, freedom of thought and speech and tolerance while retaining their religious and cultural codes. Those are examples showing that it is possible to integrate into a Western society without losing identity. Those should be empowered against radicals. Moderate voices have an important role to play in this struggle.

Daesh has been able to destroy the lives of many EU citizens enticing them with false promises. It has not only destroyed the unity in Syria and Iraq, it has also harmed the social tissue of the Muslims by opening door to radical interpretations or implementations of Islam. As Obama says, it is the Muslims that are the most affected from this problem. Therefore, it is modarate Muslims’ best interest or duty to stand against this ideology. There must be a Muslim opposition or unrest against Daesh. Much repeated “developing counter-narratives” is not a correct way forward. It denotes a passivism. Muslims should move proactively to defeat Daesh and the others of its ilk by better educating their children against its detriments. They should also educate the societies they live within by explaining what Islam is with their words and behaviors. One recent much publicized youtube video reflects the need for such. In the video, a person reads a verse from a bible with cover indicating the book is Quran. The listener thinks it is Quran that orders violence and the interviewer makes comments on Quran. Once he/she learns that those verses are in fact from Bible, the embarrassment is visual. [31] Reverting to Moghaddam’s analogy, being a Muslim or Christian alone does not push a person to the last level in the ladder. This should be well understood.

On the institutional side, European Intelligence services should cooperate to share information gathered on the ground on the fighters. As the targeted networks operate in a transnational manner, no state can tackle the problem based on solely national resources. The solution requires better governance in cooperative security approach. One such initiative was presented by Gen.Dunford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of US in June. Accordingly, a military programme called Operation Gallant Phoenix started to transfer data acquired on the field in Syria and Iraq to law enforcement units in Europe. In the same vein, UNSCR 2396 of 21.12.2017 was unanimously adopted to “to strengthen their efforts to stem the threat through measures on border control, criminal justice, information‑sharing and counter‑extremism.”[32] Such information sharing and cooperation should be institutionalized which will both stem flow of returnees and discourage further recruitments.

c. Will Daesh evolve into a “Virtual Caliphate”?

The sophisticated and skilled use of cyberspace by Daesh is a fact. From its launch of cyber jihad in 2014 till the beginning of 2017, Daesh has shared instant textual, audio, visual and audiovisual propaganda over Website 2.0 environment with unprecedented quality. This becomes even clearer when compared with others of its kind. However, since the beginning of 2017, alongside its territorial losses and decline in manpower, Daesh cyber activities has shown a constant decline in quantity, quality, and a dramatic shift in themes. [33] The findings of a report recently published by Policy Exchange indicates Daesh online content production is decentralized and dissemination is made through an interconnected network with the name ‘Swarmcast,’ a resilient and agile system that enables presence at all times despite efforts to reduce it. [34]

Parallel to its decline in battlefield its clout on cyber space is shrinking too. Charlie Winter, a researcher at International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation made a longitudinal comparison between two universes of Daesh broadcast in mid-2015 and January 2017. Although the rate of change between consequential months may be meaningless statistically, his study revealed a 50 % decline between the two studied periods. Winter also found a significant decline in the number of the highest quality products, quality video clips. To be more precise, the total number of products Daeash produced fell from 892 to 463 whereas the number of quality video clips fell from 54 to 9. While consistent with the general composition of the media items, Daesh replaced the most effective of its media tool, high-quality videos with crude, short video clips. One last element of the study is the narrative. Accordingly, the initial emphasis put on utopia has been shifted towards warfare after military setbacks. [35]

One illustrative example of such rhetorics change can be seen in the speech made by Abu Mohammad al-Adnani, notorious chief spokesman of Daesh killed by Coalition, on 21 May 2016. In the statement, Adnani tries to mask failures on the ground by developing a narrative accommodating such loss. Below is an excerpt from his speech:

Or do you think, O America, that victory is by killing one leader or another? Indeed, it would then be a falsified victory. Were you victorious when you killed Abu Mus’ab, Abu Hamzah, Abu ‘Umar, or Usamah? […]Or do you, O America, consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of land? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq and were in the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqah or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not! True defeat is the loss of willpower and desire to fight. America will be victorious and the mujahidin will be defeated in only one situation. We would be defeated and you victorious only if you were able to remove the Quran from the Muslims’ hearts.[36]

There is now a widely shared idea, an idea of a “Virtual Caliphate” circulating among media, academia and security professional circles. Based on its initial strength of using cyber platforms and due to its loss of territory and thus the caliphate, the holders of this idea believe in a phoenix which will rise from its ashes on battlefield. This new “Daesh 2.0 Virtual” will spread harm from cyber space after its total loss of territory. From this platform it will command its already radicalized citizens irrespective of borders, radicalize and recruit new militants and continue to order/coordinate attacks against the West at its own home. [37] One especially important figure advocating the same idea/prophecy is the commander of U.S. Central Command, Gen. Joseph Votel. With the article he co-authored he prescriptively claims:

Following even a decisive defeat in Iraq and Syria, ISIL will likely retreat to a virtual safe haven – a “virtual caliphate” – from which it will continue to coordinate and inspire external attacks as well as build a support base until the group has the capability to reclaim physical territory. […] ISIL’s virtual caliphate offers them citizenship free from terrestrial constraints, which can be accessed from anywhere in the world. Disaffected Muslims seeking community and purpose can find these in ISIL’s caliphate. ISIL’s alluring and dynamic caliphate narrative is steeped in religion and history and promises the restoration of dignity and might. Members need not commit violent acts or immigrate to a distant land to join the caliphate; they need only to favor the idea of an Islamic state governed by sharia and click “like” to express their support and membership in the virtual caliphate. Moreover, the ubiquity of technology in daily life and the insatiable need to be online at all times make it easy, even natural, for virtual caliphate members to operate and exist comfortably in the cyber domain.

His words have great importance because he is the commander on the field who directs the operations against Daesh. In this regard his every word requires extra scrutiny, and that is what I will do.

Daesh has proved its skill in bypassing the strict regulations and account bannings of mainstream social media platforms and has been able to communicate with its members using encrypted tools. It also can change rhetorics to compensate for a loss or color its brutal acts with religious motives. Based on those two strengths General Votel’s premise may seem justified.

However, several important points diminish the value of his claims. First, the leaders of Daesh and its operatives on the ground struggle for their lives. Many of its media operatives have been killed, and related assets have been destroyed. It is not conceivable that they will decide to change platform to regain old vigor with so many losses.

Second is a dilemma related to relationship between a product and its source. ISIL used the propaganda based on a success story on the ground with ample opportunities to film/document its artifacts. As it spread its message promising abundant opportunities to those disenchanted, seeking identity or adventure, there was a promise of land to live or a life promised. The failure of Daesh on the ground created such a great hole in its narratives that it has the potential to alienate those adhering to the organization because of its promise.

A third reason is an overestimation of Daesh’s online activities. Prof.Scott Atran, co-founder of the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict at Oxford University has interviewed captured fighters of Daesh, Nusra, and Al-Qaeda. On 23 April 2015, he addressed the UN Security Council to relate insight on Daesh saying:

About 3 out of every 4 people who join Al Qaeda or ISIS do so through friends, most of the rest through family or fellow travelers in search of a meaningful path in life. It is rare, though, that parents are ever aware that their children desire to join the movement: in diaspora homes. Muslim parents are reluctant to talk about the failings of foreign policy and ISIS, whereas their children often want desperately to understand.[38]

In the same vein, Prof.Rik Coolsaet also confirms the necessity for a social context for radicalization. He says: “One does not simply become a terrorist by watching social media messages or heroic videos. However important they may be as a means of feeling oneself part of a (virtual) community of like-minded people, in most cases cyberspace bonds need a physical extension in order for an individual to match their actions to their words.”[39]

Last, there is a wide variety of literature aiming at capturing true nature of radicalization. The generally accepted four elements to produce radicalism are grievances, ideologies, networks and support structures. In radicalization, each of those factors has relative weights based on the person or context. So, demonstration of online radicalization as the mother of all evils is a problematic approach.

It is challenging to fathom how the events will evolve from this point at time. To speak about a future “virtual caliphate” would be a big prophecy if it happens. Because this will also depend on factors that there is very limited knowledge about. Those include above all the will of the Daesh leaders. There is no open source information clearly showing this is their intended next move. Second, it will depend on the resilience of the remaining Daesh militants about adhering to its ideals despite so many setbacks and their capacity in numbers and skills. All those information is unknown to us.

Based on all those reasons, it is arguable that Daesh will still be relevant in the next decade. In these days, its operatives responsible for cyber activities and its avid followers will try to give a favorable interpretation of the losses on the ground. They will bless the struggle as a sacrifice and will try to keep the adherents bound to the organization. To keep this narrative alive and to pretend greatness, Daesh will inspire and stage attacks in the West. Yet, the more Daesh turn into a terrorist organization and become local, the more it will lose its allure as what it can promise will decline. Equally, its shadow in the cyber world will also die down gradually. If not for exterior support, building a virtual caliphate seems “not feasible” for Daesh with its current resources.

Policy Recommendations (c)

A simple communication effort requires the sender put his message across to the receiver though a channel and get feedback. So the elements required for communication are the sender, receiver, message, channel, and feedback. It has been emphasized that Daesh utilizes the cyber space [channel] aptly to transmit its message and adapts following the feedback back-transmitted from the same channel. In the struggle against Daesh all the elements of communication should be targeted. Following are recommendations that have not been voiced so far.

Daesh’s ideology and its assertions about what Islam says and what an Islamic answer would be to current problems find audience and are accepted as true among a marginal group. This ideology should be countered and its deviance from mainstream Islam -advocated by scholars for 14 centuries- should be shown. From the very beginning, there are Muslim scholars that have voiced their objection to the deeds of Daesh and their such interpretations of Islam.[40] In fact, about 70,000 Muslim clerics from across the world came together in November 2015 for the annual meeting of South Asian Sunni Muslims to pass a fatwa against global terrorist organizations to include Daesh and other Salafi-jihadist terrorist organizations. The message they wanted to convey was that they did not consider groups like the Islamic State to be true Islamic organizations and their members as Muslims.[41] However, it is not possible to mention a coordinated action to turn into a social movent. EU and Member states should help those to organize and make their voices heard especially by those within its borders.

It is widely accepted that prevention is the cheapest and simplest solution to any problem, terrorism included. If it is feared that Daesh will seduce those on the brink of radicalisation through online programmes, why cannot EU or member states cannot fund projects that offer more enticing, technologically more advance and morally more epic programmes, games and applications.

Especially religion/moral lessons in the secondary schools offer a good occasion to teach Muslim kids the true nature of their religion. A module that will teach Muslims students their religion and a small module to all students on all religions has the potential to build resilience among Muslim kids and partly prevent prejudice among those from other confessions. The content of the class can be relayed to the students through an iPad / tablet application which will heed all requirements of today’s youth. This has several strong points. First, those machines are all the rage. Second, they do appeal to all types of learners: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic.

Photo by Pixabay

Last recommendation is about the channel. Daesh uses cyberspace for all sorts of reasons, from propaganda and indoctrination to logistics and coordination. A sizable success has been attained in prevention of Daesh message propagation in social media platforms like twitter, facebook or youtube, However Telegram[42], SureSpot[43] and some other end-to-end encrypted telecommunication applications still provide safe and easy-to-access platforms for Daesh members. The CEO of Telegram Pavel Durov refused to take serious precautions to put the application off-limits to Daesh use on the grounds that it is a refuge for privacy. This argument is right in its own value. Yet a balance should be found between the privacy and protection of lives. This balance should be articulated to the tech companies to take required measures not to provide safe haven for jihadi content and its propagation.

d. Will Daesh replicate itself in one of its Provinces ?

In November 2014, Daesh announced to have added new five provinces to its so-called caliphate. The targeted impression to be given was that Daeash was succesfully extending beyond its and that its claim for control over Muslim world was well progressing. However, those claims have not been justified so far.

While Daesh is expected to lose currently its territory in Levant, fears are articulated regarding its relocation into one of its eight provinces. Until 2017, Daesh was able to transfer financial assets and its militants to its affiliates around the globe. But it has been extremely difficult to transfer finances any more. The organization rather economizes on its savings and tries to pay its fighters. Its financial resources have dried up. It raises funds by increasing taxes. The question is will Daesh transfer its core which is currently busy surviving? To make sound surmises, a deep insight is necessary into the sui generis peculiarities of those provinces, all under pressure now. They are namely: Sinai, Yemen, Libya, Hejaz, Algeria, Afghanistan/Pakistan, Nigeria and the Caucasus region.[44]

Daesh is a long rival of Saudi Arabia in its claim of ownership of wahhabism. It perceives the governing Saud family as corrupt and apostate and wants to replace them by its own adherents. As such it wants to have presence in peninsula. Despite such ambition, so far ISIL has remained after Al-Qaeda in Arabic Peninsula (AQAP) in the threat it posed. Aside from several attacks against Shiite population in Saudi Arabia, Daesh has existed more in the eastern province of Mahrah in Yemen. It has so far been able to relocate its militants in the core to this province relatively easily due to proximity and has the ability to make attacks throughout the peninsula at its will.[45]

In Egypt, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis had sworn loyalty to Daesh at the end of 2014. A terrorist organisation executing operations in whole Egypt, it raised its profile through this while Daesh took credit from its operations. The group has not been able to control territory. But it has so far targeted security forces and targeted Coptic community to stir up a sectarian divide.[46]

Yet the greatest prize among all provinces, Libya was seen as a candidate to replicate the abilities of the core. Daesh establishment in Libya was destroyed first in Darnah towards end of 2015 and then in Sirte in December 2016. As a result of the latter loss, its militants were dispersed throughout the country trying to form dormant cells in especially southern and western parts of the country, as well as in the coastal cities of Benghazi, Sirte, Zawiyah and Sabratah. Libya is important in that it connects several other countries: Tunisia, Egypt, and Algeria. Especially Tunisia is heavily affected by Daesh setbacks in Libya. Despite a core in Tunisia, many militants from Libya have commuted between the two countries especially in Kasserine and Ben Gardane regions.[47] The diminishing revenue from the core and the obvious absence of myth of success put the loyalty of the provinces in jeopardy. This is especially true for Khorasan/ Afghanistan and Boko Haram. Algeria province, on the other hand, remains a myth, no trace on the ground except for several attacks on Algerian army.[48]

So, different provinces have come together under Daesh rule with different motivations. For Daesh keeping the myth of “settle and expand” and to compensate for the losses in the Levant, it is vital to keep those provinces at hand. But, this will not be easy. As the revenues from core came nearly to nothing, some provinces need extra motivations to stay under its flag. Especially those provinces that rebranded themselves have great potential to revert to their old names, usually local focus and original modus operandi when they deem there is nothing to get more from the core. Provinces like Libya on the other hand, which was created under the direct influence of the core will rest loyal to the Daesh.[49]

Policy Recommendations (d)

To exhaust Daesh, it is important to counter the network in all of its provinces. Especially the situation in Libya is of critical importance. Libya has the potential to offer a second launch point after the Levant. This should not be allowed and constant pressure should be applied to Daesh elements in Libya. If Daesh is allowed to take hold, it will pose great threat to Europe and it will try to spread to whole North Africa, replicating its actions in Iraq and Syria. As such this future is the most dangerous among the others.

A second important dynamic is the vacuum of power. There is a negative correlation between strong state and Daesh presence. The greater power vacuum the greater chance for terrorist organizations to grip hold on the field. In this regard, security establishments of those countries hosting Daesh provinces should be supported in capacity and training.

The main problem on the field is that too many European States under NATO hat offer various military courses and outmoded equipment. This creates more problems than solutions because they create mismatch and confusion. Instead, those states should focus more on lasting solutions through educating officers in meaningful numbers and helping in the structuring of the security establishment in a holistic approach.

4. Conclusion

How will the post-Daesh landscape look is a question hard to be answered based on the multiple unknowns in the equation. The ability to give credible answers to this question as an outsider requires a deep understanding of Daesh and a vigilant following of the events with this wisdom. By merging those two, credible but not certain answers can be offered which is what this study aims to do.

The fight against ISIL and the precautions to be taken against its negative effects are generally precautions taken against the symptoms rather than root causes. The root cause for the rise of Daesh is the havoc in the wake of US invasion of Iraq, demolition of its state, disbanding its armed forces and inability to re-establish the state. Daesh and its predecessors in Iraq have used sectarian and ethnic competition to rise and find adherents. The more it has replaced the state in providing security and services the more it has found a wider social base. So the number of the killed militants and number or the reclaimed territories does not mean much. Drain the swamp and there will be no more mosquitoes. The state of Iraq should be helped to accelerate in the process of state building by owning the monopoly on the use of violence, by renewing the social contract with its citizens and attaining a social harmony. Any terrorist organization with no social base cannot maintain its life for long.

Daesh has shown superiority in using cyberspace and manipulating religious tenets to promise a false heaven and recruit new members. EU and Member States should invest more to do better than what Daesh makes to eclipse its harmful effect. The solutions found should be adapted/localized according to the contexts and inclinations of the targeted groups like the use of tablet applications and social media.

So far Daesh has shown unprecedented success in recruiting militants among disaffected Muslims in Europe. It has benefitted from their grievances and identity problems. Europe has no other option than healing this problem through breaking vicious cycle of low education – low income – low socioeconomical status. It should invest on education and empowerment of the Muslim population. It should convince Muslims that they are equal members of their societies and have equal access to education and jobs.

The worst among all other scenarios would be Daesh’s take hold in Libya. In many EU policy documents security in EU has been reflected as dependent on security neighbouring and surrounding regions. This is true. Europe should support Libya to keep it stable to preempt Daesh replicate itself .

[†] Most of those tribes would later turn against Baghdadi because of the extreme violence committed.

[1] Margaret Cooker and Falih Hassan, “Iraq Prime Minister Declares Victory Over ISIS,” New York Times, December 9, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/09/world/middleeast/iraq-isis-haider-al-abadi.html.

[2] Eric Schmitt, “The Hunt for ISIS Pivots to Remaining Pockets in Syria,” New York Times, December 24, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/24/world/middleeast/last-phase-islamic-state-iraq-syria.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FIslamic%20State%20in%20Iraq%20and%20Syria%20(ISIS).

[3] Bill Roggio, “al Qaeda’s Grand Coalition in Anbar,” FDD’s Long War Journal, October 12, 2006, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2006/10/alqaedas_grand_coali.php.

[4] The ISIS Threat The Rise of the Islamic State and their Dangerous Potential (Providence Resarch: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014), 6.

[5] Jacob Oligart, Inside the Caliphate’s Classroom (Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 2016), http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus147-Olidort-5.pdf.

[6] Fawaz Gerges, A history: ISIS (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 27.

[7] Cathy Otten, “The Long Read Slaves of ISIS: the long walk of the Yazidi women,” The Guardian, July 25, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/25/slaves-of-isis-the-long-walk-of-the-yazidi-women.

[8] During his adress to the nation on September 10, 2014 where he expanded upon US strategy to tackle Daesh, former US President Obama said: “Now let’s make two things clear: ISIL is not “Islamic.” No religion condones the killing of innocents, and the vast majority of ISIL’s victims have been Muslim. And ISIL is certainly not a state. It was formerly al Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, and has taken advantage of sectarian strife and Syria’s civil war to gain territory on both sides of the Iraq-Syrian border. It is recognized by no government, nor the people it subjugates. ISIL is a terrorist organization, pure and simple. And it has no vision other than the slaughter of all who stand in its way.” For the full transcript of the speech please consult: David Hudson, “President Obama: “We Will Degrade and Ultimately Destroy ISIL,” the White House, September 10, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/09/10/president-obama-we-will-degrade-and-ultimately-destroy-isil.

[9] Mohammed Ayoob, The Many Faces of Political Islam (The University of Michigan Press, 2008), 132.

[10] Ayoob, Political Islam, 36.

[11] Radicalisation Awareness Network, Responses to returnees: Foreign terrorist fighters and their families (RAN, July 2017), 17, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/ran_br_a4_m10_en.pdf.

[12] “What is ‘Islamic State’?,” BBC, December 2, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-29052144.

[13] Gerges, ISIS, 3.

[14] RAN, Responses to returnees, 17.

[15] Ibid, 15.

[16] Barack Obama, “President Barack Obama Speaks With VICE News,” interview by Shane Smith, Vice News, March 16, 2015, video, 12:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2a01Rg2g2Z8.

[17] United States Department of State Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, “IRAQ 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT,” [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/265710.pdf.

[18] Craig Cornfield, “A distractor or a catalyst for a chain reaction for more violence in Levant? Kurdish Referendum under Scrutiny,” Beyond the Horizon ISSG, September 24, 2017, blog, http://www.behorizon.org/kurdish-referendum/.

[19] For a better understanding of differences between terrorism, insurgency, counter-terrorism and counter insurgency following source can be consulted: Martha Crenshaw and Gary Lafree, Countering Terrorism (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2017), 17.

[20] Joel S. Migdal, Strong Societies and Weak States (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 19.

[21] Paul Cruickshank, “The inside story of the Paris and Brussels attacks,” CNN, October 30, 2017, http://edition.cnn.com/2016/03/30/europe/inside-paris-brussels-terror-attacks/index.html.

[22] RAN, Responses to returnees, 15.

[23] Eric Schmitt, “ISIS Fighters Are Not Flooding Back Home to Wreak Havoc as Feared,” New York Times, October 22, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/22/us/politics/fewer-isis-fighters-returning-home.html.

[24] Quentin Sommerville and Riam Dalati, “Raqqa’s Dirty Secret,” BBC, November 13, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/raqqas_dirty_secret.

[25] Richard Barrett, Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees (The Soufan Center, October 2017), 14, http://thesoufancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017.pdf.

[26] RAN, Responses to returnees, 17.

[27] Gerges, ISIS, 63.

[28] Afua Hirsch, “The root cause of extremism among British Muslims is alienation,” The Guardian, September 19, 2014,

[29] Ibid.

[30] RAN, Responses to returnees, 15.

[31] The Point with Ana Kasparian, “Prank Proves People Don’t Know The Bible From The Quran,” video, 7:40, December 10, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lX0Zt0OdrEA. Another person inspired by this experiment tries to conduct the same in Toronto, Canada. The reactions in this second video are interestingly much different. This difference between the reactions may explain the relatively low rate of radicalization in North America when compared to Europe. For this second video: Vincent Vendetta, “Bible vs Quran Experiment – Surprising Reactions!,” video, 4:47, December 13, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fCQ0svB0UUU.

[32] “Security Council Urges Strengthening of Measures to Counter Threats Posed by Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters, Adopting Resolution 2396 (2017),” United Nations, December 21, 2017, https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/sc13138.doc.htm.

[33] Miron Lakomy, Cracks in the Online “Caliphate”: How the Islamic State is Losing Ground in the Battle for Cyberspace, Perspectives on Terrorism, Volume 11, Issue 3 , p. 40-53, June 2017.

[34] Martyn Frampton, Ali Fisher and Dr Nico Prucha, The New Netwar: Countering Extremism Online (London: Policy Exchange, 2017), 7, https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-New-Netwar-2.pdf.

[35] Charlie Winter, “Apocalypse, later: a longitudinal study of the Islamic State brand,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 35, no.1 (2018): 103-121, https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1393094.

[36] Paul Kamolnick, “Abu Muhammad al-Adnani’s May 21, 2016 Speech,” July 2, 2016 , Small Wars Journal, http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/abu-muhammad-al-adnani’s-may-21-2016-speech.

[37] Harleen Gambhir, The Virtual Caliphate: ISIS’s Information Warfare, (Washington: nstitute for the Study of War, December 2016), 30, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/ISW%20The%20Virtual%20Caliphate%20Gambhir%202016.pdf.

[38] Greg Downey, “ Scott Atran on Youth, Violent Extremism and Promoting Peace,” PLOS Neuroathropology (blog), April 25, 2015, http://blogs.plos.org/neuroanthropology/2015/04/25/scott-atran-on-youth-violent-extremism-and-promoting-peace/.

[39] Rik Coolsaet, Anticipating the Post-Daesh Landscape, Egmont Paper 97 (Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations, October 2017), 26, http://www.egmontinstitute.be/anticipating-post-daesh-landscape/.

[40] Tom Heneghan, “Muslim scholars present religious rebuttal to Islamic State,” Reuters, September 25, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-islam-scholars/muslim-scholars-present-religious-rebuttal-to-islamic-state-idUSKCN0HK23120140925.

[41] Willa Frej, “How 70,000 Muslim Clerics Are Standing Up To Terrorism,” Huffington Post, December 11, 2015,

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/muslim-clerics-condemn-terrorism_us_566adfa1e4b009377b249dea.

[42] Rebecca Tan, “Terrorists’ love for Telegram, explained,” Vox, June 30, 2017, https://www.vox.com/world/2017/6/30/15886506/terrorism-isis-telegram-social-media-russia-pavel-durov-twitter.

[43] “Terrrorists on Telegram,” Counter Extremism Project, accessed on January 15, 2017, https://www.counterextremism.com/terrorists-on-telegram.

[44] Katherine Bauer, Beyond Syria and Iraq, Examining Islamic State Provinces, (Washington D.C.: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2016), https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus149_Bauer.pdf.

[45] UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, “ Twentieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2253 (2015) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” August 7, 2017, 11, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2017/573, pg.11.

[46] UN Monitoring Team, ISIL, 12.

[47] UN Monitoring Team, ISIL, 11.

[48] Bauer, Beyond Syria and Iraq, xiii.

[49] Bauer, Beyond Syria and Iraq, xvii.