Background

- In late March and early April 2021, Russian massive military build-up along the Ukrainian border was reported. This came after a military exercise on March 23 that did not result in the departure of troops from the region. The US officials estimated 4000 additional Russian troops had been stationed alongside military vehicles and tanks.

- On April 20, 2021, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said during an online news conference: “Russian troops continue to arrive in close proximity to our borders in the northeast, in the east and in the south. In about a week, they are expected to reach a combined force of over 120,000 troops.”

- In June 14, 2021, Brussels Summit Communique voicing the decision of 30 NATO Ally Heads of State and Government read: “Russia’s growing multi-domain military build-up, more assertive posture, novel military capabilities, and provocative activities, including near NATO borders, as well as its large-scale no-notice and snap exercises […] increasingly threaten the security of the Euro-Atlantic area and contribute to instability along NATO borders and beyond. […] We reiterate our support for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine, Georgia, and the Republic of Moldova within their internationally recognized borders. […] We strongly condemn and will not recognize Russia’s illegal and illegitimate annexation of Crimea and denounce its temporary occupation.”

- On July 12, 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin penned an essay titled: “ On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainian,” claiming the Ukrainian and Russians were the same people diversified in time linguistically. In the article, he openly said: “Apparently, and I am becoming more and more convinced of this: Kyiv simply does not need Donbas.” and threatened, saying “I am confident that true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia.”

- On December 17 2021, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a draft treaty and a draft agreement to be negotiated with the United States and NATO. The draft documents aim to prevent NATO’s eastward expansion and deny NATO membership of ex-Soviet states. They seek to limit deployment of strategic air, navy, and army assets as well as ground-based missiles around Russian “near abroad,” including Baltic and Black Seas. With the two treaties, Russia also wants to curb deployment of US nuclear weapons outside its soil, in other words, asks US to withdraw its “extended nuclear deterrence” assurances that it provided for NATO Russia seems to have left its decision on Ukraine based on the answer it will get for its treaties to the US and NATO.

- On December 3, 2021, a leaked US intelligence report suggested Russian Army was massing a force up to 175,000 troop strength along east and north east borders of Ukraine allegedly in preparation for a massive military offensive as early as 2022. Military analysts assessed that a military operation was imminent, given the size, composition, and deployment of the Russian forces.

- On January 10, 2022, Russia and US delegations met at Geneva. Russia reiterated its security concerns and demands to radically transform security structure in Europe. The meeting ended with no tangible results.

- On January 12, a NATO – Russia Council was held to discuss Russian military build-up. Russia raised the proposals that were published in December. Secretary General Stoltenberg said Allies agreed “any use of force against Ukraine will be a severe and serious strategic mistake by Russia. And it will have severe consequences and Russia will have to pay a high price.”

- On January 17, Russia began moving units to Belarus, Ukraine’s northern neighbour, joint military exercises, named United Resolve. In case Russia starts incursion, its forces in Belarus will need to move less than 100 km along the Dnieper River to reach Kyiv.

Analysis

1. NATO Strategic Solidarity with Ukraine: Testing Waters

Relations between NATO and Ukraine go back to the early 1990s, right after Ukraine gained its independence in 1991. Ukraine joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council in 1991 and the Partnership for Peace programme in 1994. NATO – Ukraine Commission was established in 2007. Since then, Ukraine became NATO’s valued partner. NATO supported westward looking Ukraine with a number of mechanisms (some of which can be found on NATO portal). In return, Ukraine actively participated in almost all NATO missions and operations (KFOR, ISAF, RSM, NTM-I, Active Endeavour, Ocean Shield and Sea Guardian) conducted after Cold War.

In line with NATO’s three-decade-long enlargement strategy, 2008 Bucharest Summit Declaration explicitly stated that Ukraine will (eventually) become a NATO member alongside Georgia (Article 23). Russia’s immediate response was to invade Abkhazia and South Ossetia after 2008 Russo – Georgian War.

Ukraine waited its turn since some sort of balance of power was struck between Russia and the West after Orange Revolution under the rule of Viktor Yanukovych and Yulia Tymoshenko. However, Euromaidan protests, leaning Ukraine more towards Europe removed Yanukovych from power. Russia, once again, intervened by annexing Crimea, and invading Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk regions).

The Russian intervention was a pivotal moment in modern European history. This was the first time after WWII that a European country’s territorial integrity was lost by force. Russia ended Fukuyama’s end of history illusion by making clear where its red line crossed. Having invested in Ukraine for decades both economically and politically, the West and NATO in particular accepted the Russian challenge. From the outset of the crisis NATO took this crisis as an Article 5 (collective defence) issue because NATO’s eastern flank countries were aware that once Ukraine falls under Russia’s control, the next battlefield would be their territory.

After 2014, NATO in general, and US and UK in particular, fully supported Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders in every way that they could. Immediately after the annexation of Crimea, NATO suspended all cooperation with Russia, increased its deterrence posture and endorsed a Comprehensive Assistance Package to help Ukraine per decisions taken at the Warsaw Summit in 2016. Military advisors were deployed to the country for providing support on key issues. Command, Control, Communications and Computers (C4), Logistics and Standardisation, Cyber Defence, Medical Rehabilitation, Military Career Transition, Demilitarisation, Radioactive Waste Disposal and Explosive Ordnance Disposal, and Counter-Improvised Explosive Devices were some of the key cooperation areas. Besides, Trust Funds were founded and led by Allies to support Ukraine. The country benefitted from well known NATO programmes such as Defence Education Enhancement (DEEP) and Science for Peace and Security Programmes (SPS).[i]

Till March 2021, Russia was rotating its units permanently deployed around Ukraine and maintaining the force posture. Nevertheless, in March, it began to deploy additional forces to the region. Currently, it is assessed that Russia massed around 60 battalion tactical groups (BTGs, there are 168 BTGs available in the Krasnaya Armiya – Red Army), along with support elements around Ukraine. A force of this size corresponds to roughly 85,000 troops, excluding reinforcements deployed in the rear area and pro-Russian militias from the Donbas region, which is believed to be nearly 15,000 persons. These numbers do not include Navy (Black Sea fleet), Air Force, Special Forces, and other strategic assets to be used in the Ukrainian theatre (or in Western Military District in general) in a possible military operation.

Since Ukraine is not a NATO member, it is not covered by the guarantees enshrined in Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. However, Allies such as US and UK actively support the Ukrainian military by sending equipment and personnel to Ukraine. On the other hand, NATO intensified its political support to Ukraine during the last month. At NATO Foreign Ministerial held in Riga on December 1, 2021, NATO Secretary-General reiterated that NATO’s support for Ukraine’s and Georgia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty remains ‘’unwavering’’. On December 16 2021, North Atlantic Council issued a statement calling Russia to immediately de-escalate, pursue diplomatic channels, and abide by its international commitments on transparency of military activities. On the same day Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited NATO Secretary-General at the NATO Headquarters.

Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a draft treaty and a draft agreement on December 17 2021, to be negotiated with the United States and NATO respectively. The draft documents aim to prevent NATO’s eastward expansion and deny NATO membership of ex-Soviet states. Russia also demands a halt to NATO enlargement. Russia seems to have left its decision on Ukraine based on the answer it will get for its treaties to the US and NATO.

An extraordinary NATO Foreign Ministerial convened on January 7, 2022, to address Russia’s continued military build-up in and around Ukraine and the implications for European security. On January 10 2022, NATO-Ukraine Commission met where Stoltenberg reiterated NATO’s support to Ukraine. On January 12 2022, both NATO’s Chiefs of Defence met virtually and had a session with their Ukrainian and Georgian counterparts. On the very same day, NATO-Russia Council met without any tangible results.

2. What Exactly Does Russia Want? De-Constructing Russian Demands and Their Repercussions

Putin is cited to have described Ukraine to George Bush at a NATO meeting in Bucharest, saying: “You don’t understand, George, that Ukraine is not even a state. What is Ukraine? Part of its territories is Eastern Europe, but the greater part is a gift from us.” Russia has long considered Ukraine, literally meaning borderland, to be parts of itself, a status that was lost with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. To Russia, Ukraine is never simply a foreign state, as Henry Kissinger put it. But it is a guarantor of Russia’s territorial integrity, alongside Belarus and Moldova. Therefore, the more Moscow perceives a significant danger of former Soviet countries like Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, or Moldova moving westward, the more determined it is to undermine, split, and keep the West busy in its efforts for greater integration. From the superpower image perception of Russia, the breakup with Ukraine is a historical blunder and a danger to Russia’s status as a great power and its interests. Especially NATO and US involvement in military development of Ukraine is a no go and great offense. This is true even though Ukrainian Armed Forces to be a match for Russian Armed Forces impossible in the foreseeable future.

Further, Russian historical experiences suggest that having some control over its western periphery is a smart option. As seen from Moscow, NATO has been creeping closer and closer to Russia’s area of influence, manifesting themselves in the colour revolutions and following events. The reason of Russian fear is not merely about the security risk emanating from proximity of the Western influence, but it is a matter of a fact that such democratic change or as Putin has described “managed democracy” could spread easily to the homeland, Russia, and be resulted in a regime change.

For decades, from an economic or interdependency perspective, Russia has relied on Ukrainian pipelines to transport its gas to Central and Eastern European clients. It continues to pay Kyiv billions of dollars in transit costs. It should be noted that one of the terms agreed by Putin in North Stream 2 was that a certain amount of gas from Russia to Europe would flow through Ukrainian pipelines to help Ukrainian economy with transit fees. On December 20 2019, Russia agreed to five years of volumes of natural gas to flow to Europe through Ukraine.[ii] Russia was Ukraine’s major commercial partner for a long time, even though the relationship has deteriorated considerably in recent years. Further, to explain interdependency, it is worth to mention that some Ukrainian businessmen and politicians have formed an unofficial economic web with Russia, which is counterproductive to Ukraine’s efforts to build an independent judicial system and a free market, fight corruption, reform its energy structure and industrial base, attract foreign investors.

Considering all these issues, Moscow has come to view Ukraine’s general political direction of critical interest. Today, once again, European security is being severely tested as Putin masses Russian troops on Ukraine’s border. Day by day, we are witnessing a rhythm of war louder rather than a path of de-escalation and diplomacy. This picture is exactly what Moscow wants to see until it receives an assurance that Ukraine will never be admitted to NATO and that the alliance’s growth in Eastern Europe would be halted. Russia displays that, unlike the Western camp, Russia is ready to take any required action including waging a total war. As Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau, the OSCE chairman, warned, the “risk of war in the OSCE area is now greater than ever before in the last 30 years.” Russia will never hesitate to exploit the Western geopolitical inertia because Moscow knows very well that neither of the Western states will deploy their own troops. Yet, they only provide military aid and diplomatic support.

3. What Does Ukraine Want?

Ukraine wants security and the Ukrainian people wish to preserve freedom of choice and their own identity. Ukrainians have taken necessary lessons from history, and clearly see by experience from the ongoing war with Russia the existential threat approaching to themselves.

It would not be realistic to expect West to fight alongside Ukraine against Russia. Yet, Ukrainians ask for more support to prepare for the potential Russian incursion by increasing resilience thanks to additional security and military assistance — specifically, air and naval defense.

Since 2014, Ukraine has managed to develop its own military capabilities based on Western assistance. Still, it is not comparable to Russian military forces. This more developed armed forces mean higher level of attrition in case of confrontation with Russian Armed Forces. Yet, the authoritarian leadership of the Russian Federation does not feel bound by the potential loss of Russian soldiers’ lives, and the by disapproval of the Russian society.

Putin blackmails the US and the other Western countries with the threat of a full-scale conventional conflict in Ukraine – which doesn’t mean that there are no aggressive plans of invasion for other countries. Apparent aim is to change the approaches to European and world security. Moscow has succeeded partly in its blackmail which has not only force the US and the Allies to deliberate and respond to Russian promoted doctrines of “spheres of influence” of great powers and the idea of “limited sovereignty” for the neighbours of those great powers, but it has also opened door to negotiations on very important and sensitive issues of the Strategic Stability.

Ukraine’s security is directly dependent on the intention of the West to defend its doctrines and values and its unity in this intention. That includes “no spheres of influence” principle and NATO’s “open door” policy. These two principles are not about Ukraine’s joining NATO but about the sovereign right for any country to choose its destiny.

Ukraine needs close cooperation with its allies and partners to choose its own path. Their support and partnership will remind Russia that Ukraine is not alone. Another guiding principle in partnership between the West and Ukraine worth mentioning is “Nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine”. Time and history have shown that Ukraine’s warnings about Russian policy were not alarmist manifestations but rational and evidence-based positions.

4. US and Western Position on the Russian Demands

In close cooperation with Allies, the current Biden Administration has been leveraging a clear language in showing diplomacy as the optimal way out while exploiting ambiguity on how they will respond to the Russian “propaganda by deed”. The White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said on January 18: “We believe we’re now at a stage where Russia could at any point launch an attack on Ukraine. It is the choice of President Putin and the Russians to make whether they are going to suffer severe economic consequences or not.” Then she said, “No option is off the table.” In his call with President Putin, President Biden also leveraged the threat of sanctions “like none Putin’s ever seen.”

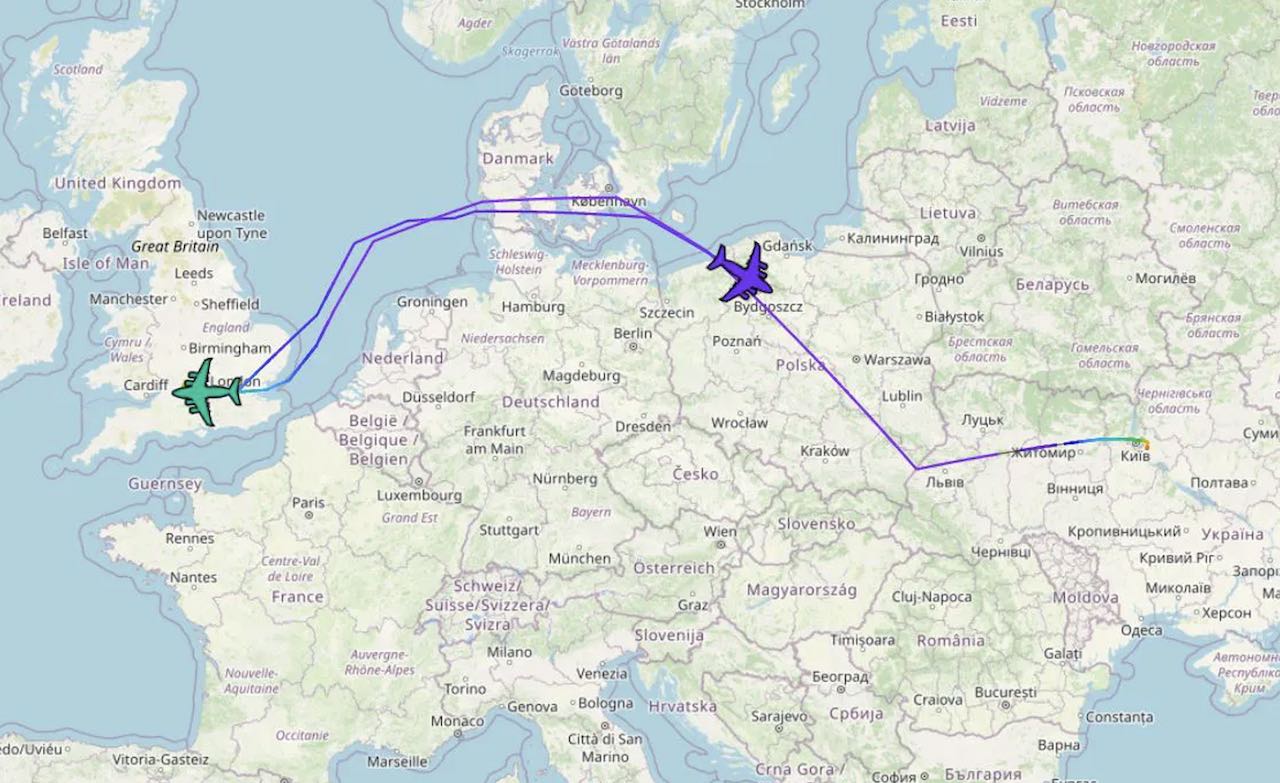

From European side, on January 19, UK Defence Journal reported British C-17 transport aircrafts were in their third day of delivering “thousands” of defensive “Next Generation Light Anti-Tank Weapons” or NLAWs to Ukraine. The NLAWs that are produced by Saab single soldier missile systems that rapidly knock out any Main Battle Tank in just one shot by striking it from above, where the armor is the weakest. On January 17, the Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace stated in the House of Commons: “We have taken the decision to supply Ukraine with light, anti-armour, defensive weapon systems. A small number of UK personnel will also provide early-stage training for a short period of time, within the framework of Operation ORBITAL, before then returning to the United Kingdom. This security assistance package complements the training and capabilities that Ukraine already has, and those that are also being provided by the UK and other Allies in Europe and the United States. Ukraine has every right to defend its borders, and this new package of aid further enhances its ability to do so. Let me be clear: this support is for short-range, and clearly defensive weapons capabilities; they are not strategic weapons and pose no threat to Russia. They are to use in self-defence and the UK personnel providing the early-stage training will return to the United Kingdom after completing it.”

Figure 1. Screenshot of flight tracking software showing two British C-17s in flight at various part of their journeys to and from Ukraine (Source: UK Defence Journal)

On January 18, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, during a joint press conference with her counterpart Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said: “The Russian troops’ build-up near Ukraine had “no understandable reason” and it was “hard not to take as threat.” Referring to Europe’s fundamental values, she said “Those common rules are the foundation of our common European house. For Germany, they are our basis of existence. Therefore, we have no other option but to defend those common rules, even if this means paying a high economic price.” She said even the Nord Stream 2 pipeline was on the table.

On January 19, one day after return home from Ukraine, a bipartisan Senate delegation briefed President Biden on their impressions. The Committee informed that the Ukrainians were glad for the President sent them more defensive weapons. President Biden said he cautioned President Putin that “a ground war in Ukraine would cost the Kremlin dearly in blood and treasure.” On the same day Secretary of State Anthony Blinken arrived Kyiv where he spoke with Ukrainian President Zelensky, the latter thanking him for the US decision to deliver an additional $200 million in defensive military aid. On January 20, Blinken will move to Berlin to meet his German counterpart Annalena Baerbock and representatives of the Transatlantic Quad, including France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. The next day on January 21, Blinken will meet his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov in Geneva.

There is need for a strong US leadership in orchestrating Western response to the Russian demands and dissipating concerns in various European capitals against consequences in case diplomacy fails. The Biden Administration has so far seems well positioned to bring together major European powers in this regard. Still, the result is to be seen.

5. Europe’s Position

It is not a secret that Ukraine has a very special place for the EU among other neighbouring countries and the EU wants to develop deep and comprehensive relations with Ukraine. The relations started as early as 1998, when the Partnership and Co-operation Agreement entered into force. This agreement is succeeded by an Association Agreement and a complementary Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement for further economic integration and political association.

However, the absence of political will and unity in the EU on Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) in general, hinders EU to defend its external interests (like those in Ukraine) in a bunch of policy areas other than trade & economy. Despite the rhetoric that the EU, contrary to NATO, has a wide range of instruments, it is not supported with evidence.

To illustrate, the EU has vigorously and decidedly launched a set of restrictive measures and sanctions as soon as Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. Apart from adding a few more entity and person, the EU has only been extending the restrictive measures regularly. Moreover, the extensions became more and more difficult with several member states reluctant to continue with the sanctions regime against Russia, prioritizing mostly their national economic (Netherlands), energy (Germany-NordStream2), cultural/religious (Hungary/Greece) or other interests with Russia.

This political disunity weakens EU’s hands in its claim to be a global actor. Russia manipulates the absence of unity & one voice and opt engaging with the Member States instead of the EU institutionally. In a striking example, Russia exploited EU HR/VP Joseph Borell’s controversial visit to Moscow with harsh and undiplomatic rhetoric in the press brief, to further weaken the EU as an institution.

Although Ukraine’s territorial unity and security are very much intertwined with that of Europe, the EU seems to have been already delegated European security to NATO, contrary to the discussions around “Strategic Autonomy”. Delegating it to NATO (read it as the US) might be understandable following WWII and during Cold War. Nevertheless, the EU should pursue a more nuanced and independent role for its security.

To sum up, the EU has to make full use of its instruments (other than trade and economy) to de-escalate the situation, or it will have to follow the US actions not to face the consequences on its own.

6. Energy Card

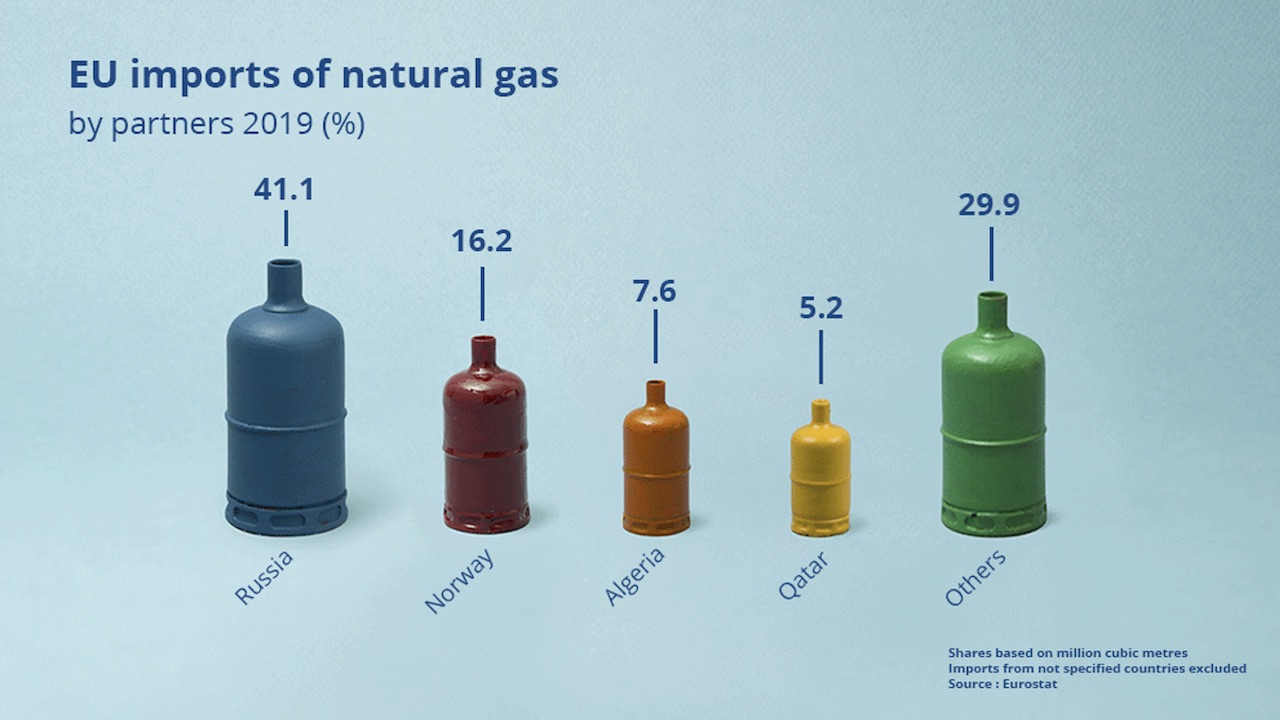

Russia is one of the Big Three -the others being the US and Saudi Arabia- in petroleum production globally. In terms of natural gas, it is the largest exporter and the second-largest producer, following the US. The energy giant answers to 41.1 percent of the European gas needs. 16.2 percent of the remaining is exported from Norway, and 7.6 and 5.2 percent from Algeria and Qatar respectively, in LNG form. Natural gas makes up 27 percent of European energy consumption and as such Russia’s share in overall European energy production is around 12 percent. So, the question of “what happens in case Russia shuts gas flows to Europe in case the latter takes a hard stance in the eventuality of incursion into Ukraine?” makes European leaders think twice before calibrating their response.

Figure 2. EU Imports of Natural Gas (Source: Eurostat)

In the past decade, the EU smartly implemented some principles that turned Europe into a single gas market where sellers and buyers meet instead of the previous regime of long-term energy commitments coming with building up pipelines that increased dependency on one energy supplier. With the annulation of destination clauses and the linking of pipelines, shifting gas from one buyer to another has contributed to this.[iii]

Other elements of EU strategies include diversification of suppliers that include building up the Southern Gas Corridor planned to carry Azeri gas to Europe. Its European leg, Trans Adriatic Pipeline became operational with annual transport capacity of 10 bcm of gas in 2020. Other projects include a 1900 km pipeline connecting 20 bcm of Israeli gas to Europe.

LNG has been an option. EU has promoted building up of LNG terminals. Addition of new terminals across Europe totaling to more than 30 has contributed to lessening energy dependency. Construction of more terminals is under way. The US has been keen to present itself as an alternative supplier of LNG to decrease European dependency on Russian gas. Former President Trump is cited to have boasted of supplying allies with “molecules of US freedom.” As more European states build new LNG terminals, LNG becomes an option that more policymakers revert to. This replacement for Russian gas though contributing to lesser dependence, is costly.

According to Enerdata, 2020 saw a 24 percent surge in US LNG exports and 9.7 percent in Australian. The year also witnessed a 4.4 percent growth in Asian LNG imports due to rise in LNG imports in China and India (+12 percent and +8.6 percent) offsetting lower imports by Japan and South Korea (-3.7 percent and -1.9 percent respectively), due to increased share of nuclear and renewable in their respective energy mix. The latter trend was observed in EU with a 7.6 percent decline due to decline by -16 percent in France and -6 percent in Spain. This decline was possible due to increased share of renewables, reducing gas-fired power generation. This continuing increase in LNG production clearly shows a new potential for Europe to exploit. By incentivizing its LNG with advantageous price for European Allies, the US can help reduce European dependency on Russian gas, a fact that it has been warning for long now.

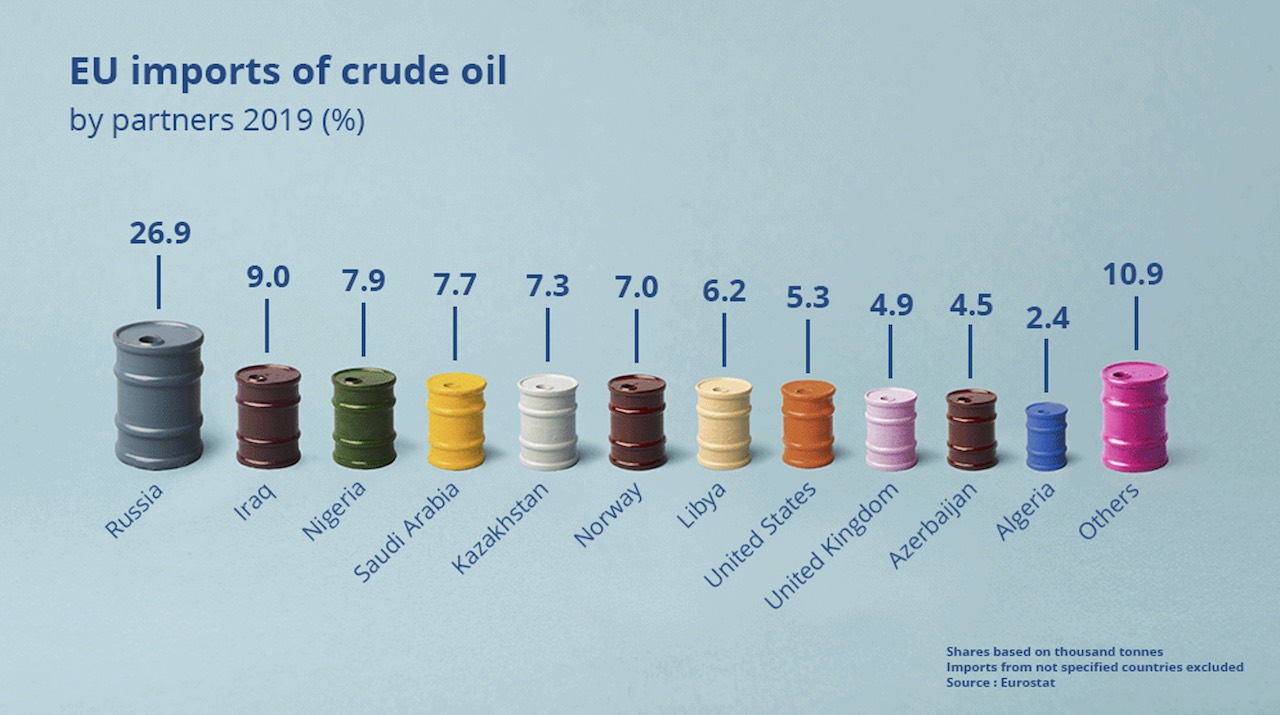

In petroleum, the market is already flexible and allows for maneuver and as such does not require mentioning here. Russian dominant share with 26.9 percent of European oil imports can be overcome by reverting to other suppliers.

Figure 3. EU Imports of Crude Oil (Source: Eurostat)

Overall, the European trends in regulation of the energy market, diversification of suppliers and supply routes, increase of share of renewables in national energy mix, and increased role for LNG have been steps in the right direction to alleviate dependency on Russian gas. Yet, as we observed in the case of Russian decreasing level of gas to Europe after the rise in energy prices last winter, Europe is still dependent on Russian gas, and it cannot find direct alternatives immediately. An agreement with the US especially that exported 56.8 bcms of LNG in 2020 can be the first step until renewables catch up with the need in optimal prices.

Strategic Foresight

In any eventuality, this latest escalation will have far-reaching repercussions, extending Ukraine. Europe and the US, although having been on constant watch, have felt closely heard and felt Russian worldview and concerted efforts to reshape global security landscape fundamentally, yearning for the Cold War era. In this troubled time, NATO has proven its value for Eastern European Allies and the need for greater military spending to secure Europe has become clear. Europe is now cognizant of its limitations in speaking in one voice. It is likewise aware of the cost of dependency on Russian gas, an issue that has been time and again repeated by each US Administration.

As for the issue at hand, President Putin does not seem willing to back down his demands. Hence ill decisions and their repercussions might lie ahead through the coldest and darkest days of the Cold War, as Denmark’s Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod said. Russia will highly likely continue to exploit the Western camp inertia and fear of losing comfort zone, and accordingly insist on taking a guarantee on the paper. It seems that Russia do not want to pursue diplomacy at all, instead, with hard balancing, it is preparing for every eventuality which ensures Russian psychological and decision superiority against the West. It won’t be a surprise if this path is ended up with Ukrainian neutrality in the most probable scenario, or a new limited war and frozen conflict in the most dangerous scenario.

If the diplomacy or deterrence fails or if one side intentionally escalates the crisis, we might face a new Russian invasion employing distinct features from the first invasion. Instead of protracted hybrid warfare as Russia launched between 2013-2016, in this last initiative Russia would highly likely conduct limited but disruptive military operations while shaping geopolitical landscape in its favor. Russia would most likely use vast cyber and electronic warfare equipment, as well as long-range hypersonic missiles, if it invaded Ukraine. The goal would be to instill “shock and awe” on Ukraine, leading its defenses or will to fight to crumble. This new Russian approach does not necessarily mean that Russians will not use non-kinetic political warfare ways and means. Russia would likely continue to export corruption, use illicit money flows and finance pro-Russian groups in Ukraine, use blackmail, launch covert activities of politically connected gangs, NGOs, conduct psychological warfare, spread disinformation and fake news.

On the other hand, with the help of external support such as the US Stingers, Iron Dome, Mi-17s (which were being readied for Afghanistan by the US), counter-artillery radars, Javelin anti-tank missiles or NLAWs, or Turkish drones, better command and control, electronic warfare, and reconnaissance capabilities might help Ukraine. Moreover, a military hardened by seven years of fighting in eastern Ukraine might cause high costs than Russian leaders expected, or a prolonged Ukraine resistance. Thus, if ground troops fail, Russia may raise the stakes by carpet bombing, as it did in Chechnya and Aleppo.

The US and Europe should prepare for the worst to come. This preparation should, inter alia, include efforts to:

- Create the strongest deterrence to make Russia back down from an incursion,

- Provide strong support to Ukraine to define its own future in the face of a probable incursion,

- Be prepared for future similar provocative actions of Russia and re-evaluate its toolbox to deter them,

- Consider sanctions and their side effects on Western investors, and think innovatively on probable alternatives,

- Cooperate and seek favourable pricing for EU members with alternative LNG suppliers to include US, Qatar, and Australia to alleviate dependency on Russian gas.

[i] For more details, please refer to NATO’s Support to Ukraine Factsheet.

[ii] Daniel Yergin, The New Map: Energy, Climate and The Clash of Nations, Penguin Books, 2021, p.107.

[iii] Ibid, p. 86.

(1) Samet Coban is a research fellow and project coordinator at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. His research area covers Security and Defence, NATO and Afghanistan.

(2) Hasan Suzen is CEO at Beyond the Horizon ISSG and a PhD researcher at Antwerp’s University. His research area covers the Russian Intervention Playbook and Great Power Competition.

(3) Olena Snigyr is Associated Fellow of the Center for Global Studies “Strategy XXI”; Head of Department of International Cooperation, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance.

(4) Onur Sultan is a research fellow and project coordinator at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. His research area covers Security in the Middle East, radicalization and polarization, and Yemen.

(5) Saban Yuksel is a research fellow and project coordinator at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. His research area covers Geopolitics and EU Affairs.