Several French parliamentarians were not content from the speech, stating Macron was stigmatizing Muslims by singling them out among other societal divisions (Euronews, 2020). In this regard:

Manon Aubry, a left-wing member of the European Parliament tweeted “Stigmatising Muslims, this is his only solution to try to hide his calamitous management of the health and social crisis.” Alexis Corbière, a French MP from the left-wing party La France Insoumise, said Macron had only talked about radical Islam instead of focusing on an increasing gap between rich and poor and other societal divisions that, he said, influences “separatism” in poorer communities (Euronews, 2020).

His speech created rage across Muslim majority countries too. Responding to the events and rhetoric of free speech and Islamist terrorism that gained currency in France, Al-Azhar Observatory for Combatting Extremism posted on October 18 on its Facebook account: “Stigmatizing Islam with terrorism reflects ignorance of this noble religion, marks an attitude that lacks respect for other people’s faith, expressly incites violence and reversion to the barbarism of the Middle Ages, and blatantly provokes the sentiments of around two billion Muslims.” Then on October 21, Prof. Ahmed Al-Tayyeb the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar said: “Offending religions and denigrating their sacred symbols under the slogan of freedom of expression is a dysfunctional ambivalence and an explicit call for hatred” (Al-Azhar Observatory for Combating Extremism, 2020).

Not all reactions had the same neutral tone. Political leaders espousing political Islamist agenda, like Erdogan and Khan were quick to denigrate French President. In fact, President Erdogan went as far as to claim President Macron needed mental treatment (Sozcu, 2020). Far-right party leaders were some others that rubbed their hands for their good luck.

This paper does not seek to understand if Islam is in crisis or not. Nor does it seek to understand calculus behind President Macron’s aims and intentions when making the statement. But it aims to test the validity of the claims, provide alternative reading to attain a balanced view and make policy recommendations.

Rubber Hand Illusion

Rubber hand illusion refers to an experiment where a person is asked to put his or her real hand beyond vision while keeping visual contact with a rubber hand. In the experiment, both the real and rubber hand are stimulated by strokes of a feather. After several minutes of synchronous stimulation of the rubber hand under visual contact and unseen real hand at the same time, the brain shifts its sensing functions on visual faculties. In other words, after a while the person starts feeling imaginary pain in case the rubber hand is brought close to a lighter fire or pricked with a pin. Interestingly, (s)he does not feel anything at all towards same stimulations, i.e. the prick or the approaching fire in the real hand.

This rubber hand metaphor can create a good understanding on French experience with radicalization and its conflating it to imperfection in Islam. President Macron is indeed right about the shift in Muslim societies in the last 30 years. But attributing the reason for the radicalization challenge in France to solely a crisis in Islam and stating this shift in Muslim world as its evidence is a claim to be tested.

A much-repeated dictum in statistics is that “correlation does not mean causal relationship.” The geopolitical condition that has become a real test case for the mentioned geography has created observable negative sociological changes, exhibiting a certain correlation between hot spots on the globe and this religion. But deciding on if it is Islam that causes this deterioration needs more scrutiny.

Third Wave of Civil Wars

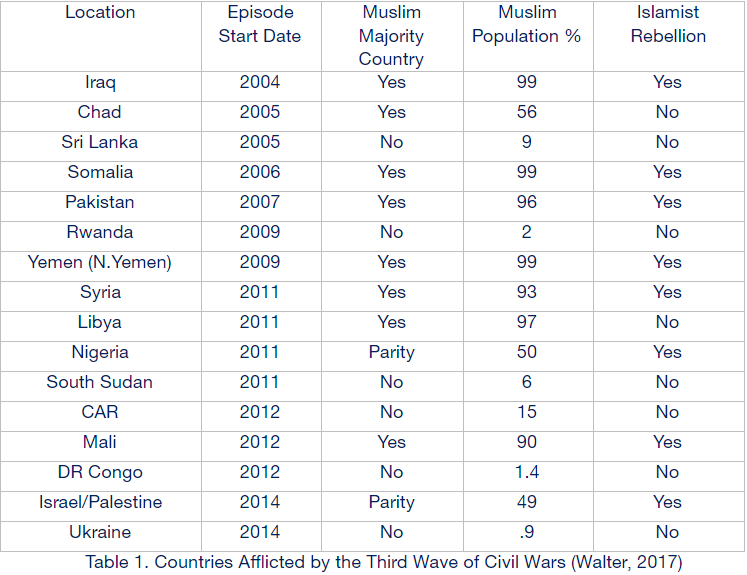

Barbara F. Walter, in her article The New New Civil Wars clusters civil wars in three distinct waves since the end of World War II: a first wave from 1951 to the end of the Cold War, a second wave from 1992 to 2001, and a third wave from US invasion of Iraq in 2003 up till now (2017). Although the last thirty years corresponds to the 2nd and 3rd waves, a closer look at the third wave shows it is the exact picture Macron refers to.

Drawing attention to the significant rise of civil wars since 2003, Walter differentiates this third wave of civil wars from the previous ones through three defining features:

- The majority of them are situated in the Muslim-majority countries (65%),

- The vast majority of the rebel-groups in fighting hold radical Islamist goals, and

- Most of such groups pursue transnational aims rather than national ones.

She further argues, this new wave of civil wars tends to last a long time, involve multiple fighting factions, feature significant outside involvement and reflect deep societal divisions.

Walter in fact verifies Macron’s claims that the landscape in Muslim majority countries in the last 30 years, but especially in the 20 years has changed significantly. But the reasons she gives for this change is a bit different. She says: “Existing macro-level studies help illuminate why so many civil wars have broken out in Muslim majority countries. Chad, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, Nigeria, Mali, CAR and Yemen are all countries where GDP per capita is low, unemployment is high, and governments are repressive, corrupt and unconcerned with the rule of law.” All in all, she attributes the reasons for the unrest in these countries to poverty, repression, significant outside involvement and deep societal divisions.

Role of Radical Ideologies

But still, we need to be able to explain the reason why radical interpretations of Islam are espoused by the fighting groups in so many civil wars. Basing her calculations on Stanford CISAC database, Walter estimates Salafi-jihadist groups make up some 35% of the major militant groups in Iraq, 50% of such groups in Somalia, and 70% of them in Syria (Walter, The New New Civil Wars, 2017). Why has this ideology become so much prevalent in the civil wars we observe today?

Walter explains this in another article with the name The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars. She argues espousing an extreme ideology like Salafi-jihadism offers rebel entrepreneurs “significant organizational advantages over more moderate groups.” Accordingly, irrespective of whether they believe in underlying core tenets or not, embracing extremist ideologies help leaders overcome collective action problem, using the ideology as vehicle or tool to raise units of men ready to accept the cost of fighting and death. As opposed to secular groups that offer money, security and material rewards, Salafi-jihadist organizations bring the cost of death to zero, offering heaven in an afterlife instead of material offers. The second advantage is that extremist ideologies help overcome principal-agent problem. They show utility in raising committed fighters that require less control and help curb side-switching, betrayal or poor performance. More devoted fighters show more audacity in the conflict. The third advantage is that they serve as an assurance that once in power, the leaders will resist corruption. Walter says:” This is especially important in countries with few institutional constraints on government elites and a history of exploitation.” So, an extremist ideology that requires personal sacrifice of the leaders function as motivator for lower-level fighters to make more efforts in the same direction. This last advantage has two aspects in reality, one that has influence on in-groups and another on average citizens taking position vis-à-vis such groups in their vicinity. The belief that leaders of extremist groups will not yield to corruption once in power is one of the two main factors that earn them average citizen support, the other being belief in high chances that respective group will win the war.

So, as can be understood above, there is a mathematics behind use of certain extremist ideologies and how support behind those ideologies from in- and out-groups form (Walter, The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars, 2017).

Why Do Radical Ideologies Find Audience in Europe?

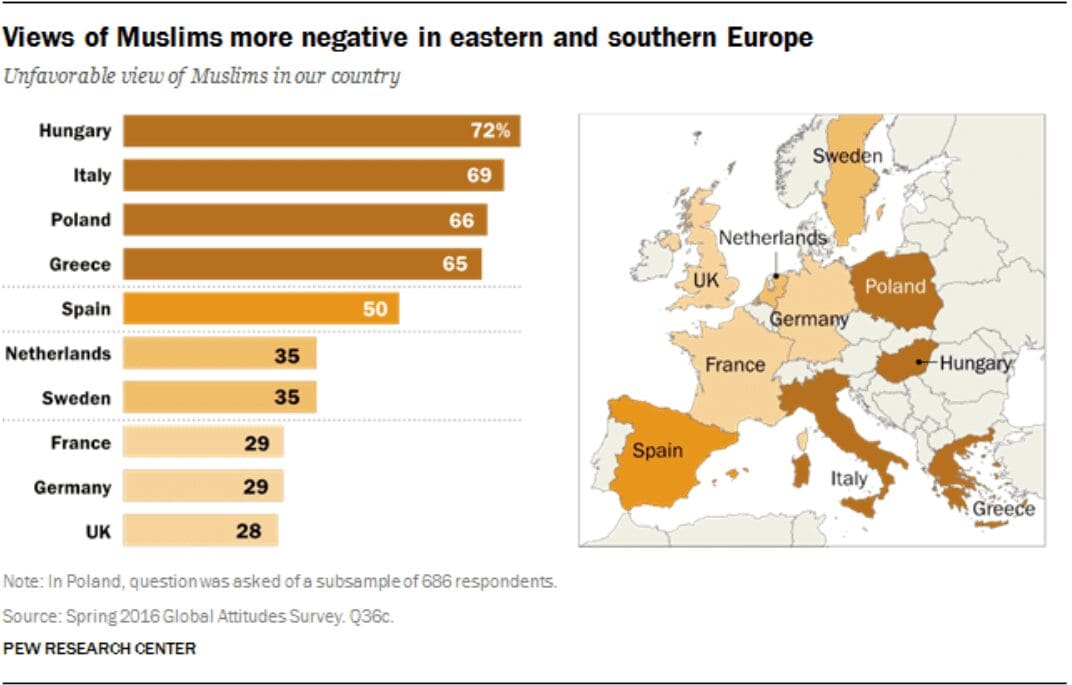

Many reasons can be cited, varying from case to case and often specific to the context. But, an important factor to be cited is the identity crisis or an effort to find his / her place in the society. Initially taking flight after 9/11 attacks, change of attitude towards Muslims and discourse conflating Islam to terror and securitization of the Muslim identity has been a reason for identity crisis, alienation and polarization (Hafez, 2015). This polarization has functioned as both a reason and a result of radicalization. So it is arguable that, inter alia an important cause of polarization is prevalent negative stereotypes about Islam and Muslims. This has further caused in a chain reaction lack of integration and thus low-level representation of the Muslims in public space, public discourse and policies. A Pew Survey conducted in Spring 2016 in 15 European countries shows especially in southern and eastern Europe, i.e. Hungary, Italy, Poland and Greece, rate of citizens holding negative views towards Muslims can be as high as 72 percent (Pew Research Center, 2016).

Along the same lines, in their article on challenges to create counter-narratives, Speckhard and Shajkovci argue: “The main recruiting pool for groups like ISIS are Muslim converts and second-generation Muslim immigrant communities who have not found the promises of the EU to match their daily realities. In formal and informal interviews with hundreds of EU citizens to date, ICSVE researchers have found sentiments of Islamophobia, discrimination, and marginalization to be widely prevalent in their daily lives and experiences (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2018).”

In fact, the number of people that join such groups directly for ideological reasons is low. In his piece where he presents the case of two ISIL terrorists, Mehdi Hassan says before their journey to Syria, the two books they bought from Amazon were “Islam for Dummies” and “Koran for Dummies.” He further continues:

In 2008, a classified briefing note on radicalisation prepared by MI5’s behavioural science unit was leaked to the Guardian. It revealed that, “far from being religious zealots, a large number of those involved in terrorism do not practice their faith regularly. Many lack religious literacy and could . . . be regarded as religious novices.” The analysts concluded that “a well-established religious identity actually protects against violent radicalisation”, the newspaper said (Hassan, 2014).

Redouan Safdi, an imam that is involved in the deradicalization of FTFs alongside home-grown terrorists and radicals in a Belgian prison designed for terrorist offenders says about his encounters with radicals and returnees: “They would usually start talking about that they have love for Islam, they want to live in an Islamic state, they want to live somewhere where shariah is implemented. When you go deeper with them in the conversation, when conversations are more meaningful, I would hardly hear them speak about Islamic state or the implementation of shariah. All I would hear is the injustices they have experienced in the past: racism, discrimination, poverty, lack of opportunity. […] The majority of them are very young people. Many of them haven’t even reached the age of 18. They are frustrated, alienated socially. Young people who are in search of identity, a meaning in life. Young people that did not feel at home in their own countries where they were born, who felt they were not appreciated” (Safdi, 2020).

If we accept travel to a conflict zones like Syria and Iraq to join various jihadi groups as a positive answer to the call from radical extremist groups, an interview conducted by the author in February 2019 reveals the role of ideology. The interviewee, a social worker in Brussels, said: “In each case we see a person making the travel to Syria and Iraq, if we scratch the surface [if we delve deeper into the issue], we find a familial, social or economic problem.”

President Macron attests to this diagnosis in his October speech where he says:

We ourselves have built our own separatism in our neighborhoods, creating ghettos in the beginning with the best intentions in the world. But we let it happen, that is to say that we had a policy, we have sometimes called it a settlement policy, but we have built a concentration of misery and hardship, and we know that very well. We have concentrated populations often according to their origins and social backgrounds. We have concentrated the educational and economic difficulties in certain districts of the Republic (L’Élysée, 2020)

France and Radicalisation

France is a country with some 5 million Muslims corresponding to roughly 9% of the population. Initially coming to take menial jobs like construction and car manufacturing in the 1970s, with the new generations Muslims started to get better education and better positions. The more they came to the public view with their lifestyles and world views, the more far right seized upon it as a threat to the French identity. The secular identity of the state called “laïcité” and its use to limit religious signs in most cases influencing Muslims has been a reason for strained relations between Muslims and the state (Ganley, 2020).

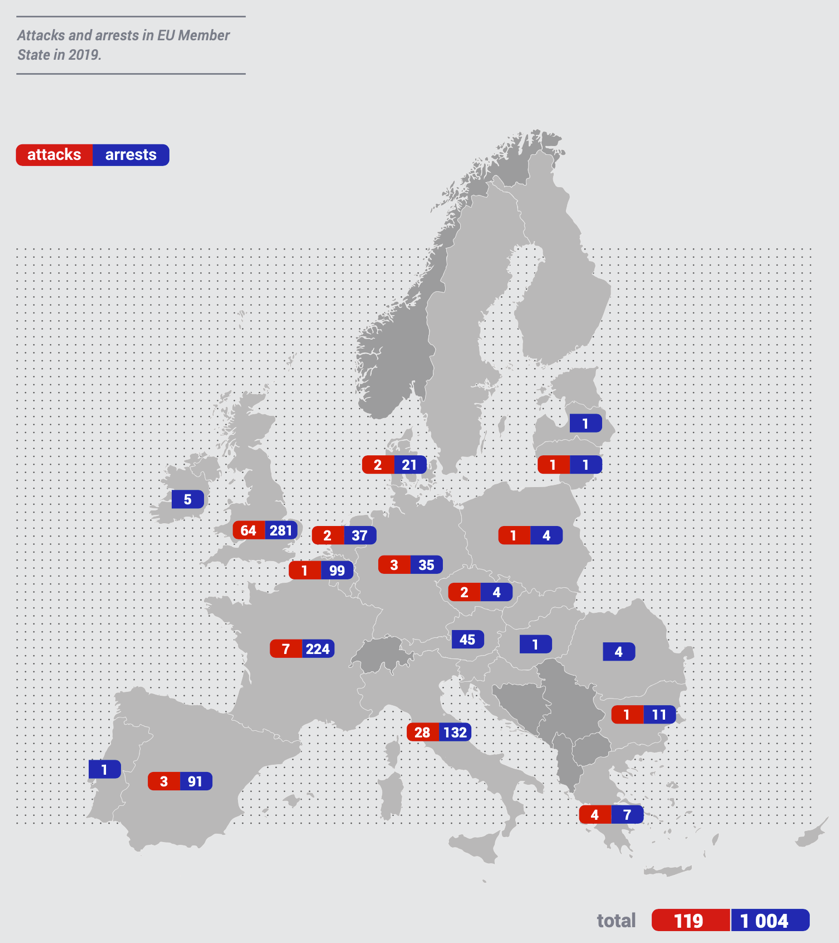

France has been a target of jihadi attacks since 1994. But, the joining of a great number of French nationals to the Islamic state, the Charlie Hebdo shootings and Paris attacks has carved the importance of the issue of terror and radicalization into the mind of the general public. To lay bare the importance of the former, 1910 French nationals have been reported to travel to Syria and Iraq to join various jihadi groups or have been stopped on the way. This figure corresponds to nearly 40 percent of the total 5000 from the EU (Barrett, 2017). Unfortunately, the issue still maintains its importance. According to TE-SAT European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2020, in 2019 France witnessed 7 terrorist attacks and 224 terror-related arrests, responding to the greatest number across the EU in both categories (EUROPOL, 2020).

Despite the greatness of this problem of radicalization, it is not possible to say the country has developed required reflexes to counter this threat. In the past years, France has been mentioned more about its failures than its successes about putting up programs of disengagement, deradicalization, rehabilitation and reintegration (Jacinto, 2017) . In the country, few non-profit organizations and private initiatives offer competent assistance to the radicalized individuals and help solution of the problem (Schwarzenbach, 2019). Yet, the number of French nationals believed by security forces to pose threat increase within “fiché S” or S file. Reuters reports there are about 26,000 people in the file about 10.000 of which are believed to be religious extremists (Salaün, 2020). As the number increase so does the inability of the French state institutions to track and deal with so many people.

Policy Recommendations

The statements by the President Macron has became a tool for manipulation by political Islamists, far right parties and Salafi-jihadist organizations alike. We have been seeing attacks across Europe since his speech on September 2, which such terror groups use to increase their brand value and visibility. France is at crossroads to adjust its position vis-à-vis its 5 million Muslim citizens in application of “laïcité” to find the delicate balance between countering radicalization and mending its social contract. Here are several considerations and policy recommendations in this regard:

Fighting radicalization towards all types of violence (jihadi, extreme right, anti-Semitist, etc.), polarization and hate speech should be the norm. But conflating radicals and extremist groups -who feed on manipulating certain religious texts- as the representatives of a certain religion when doing so, will not help anything else than providing bullet to the propaganda machine of the political Islamists, far right parties and such marginal groups. This will further erode legitimacy basis of the respective state, estranging citizens towards the itself.

France has every right and obligation to take necessary measures to stem radicalization leading to violence on French soil. But before launch of any initiative, there is one overarching pre-condition that should be satisfied. The state agents and institutions have to be perceived by all citizens as acting in accordance with the standards of a just procedure which implicates neutral and transparent decision making, and fair and respectful treatment. This way the French state will gain the trust of its citizens and its legitimacy in their eyes. This will help “minimise structural and cultural inequalities and empower marginalised individual or groups, and thus address macro-level grievances assessed to have a role in the prevention of terrorism and radicalisation” (Schwarzenbach, 2019, p. 105).

The latest support of Macron and other political figures to the caricatures as “right to blaspheme” under free speech functions as a divisive force in France and through the discussion created, in the globe. Forming a central tenet of liberalism, harm principle says individuals’ freedoms terminate at a point where it causes harm to the others. Although there is no agreed definition, UN defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.” The events we have observed in each time the caricatures have been published (in Denmark and France) pushes us to conclude on their provocative nature. Based on harm principle, definition of hate speech and the life loss each time they are published, they should not qualify for being subject of free speech.

France, with all its troubles about radicalization, should avoid political maneuvers that will further polarize French society. Instead of considering the phenomenon as representation of a certain religious ideology, the roots of radicalization should be sought in social crisis. Instead of stigmatizing Muslims and deepening the divide, France should seek ways to renew the social contract with this community.

Although sharing huge commonalities, Islam and Christianity have different historical evolutionary paths, varying mechanics in terms of openness to reform and differences in positioning God, prophets and art. Labelling radical ideologies espoused by an extremely marginal group not having any right or power of representing Islam as the latter’s plague, and packaging measures to counter radicalization as an effort to reform Islam naturally enrages Muslims and opens a vast space for abovementioned groups that feed on divisions and contentious issues. Especially for violent extremist groups, the developments opened up an opportunity to increase the volume of their propaganda by words and deeds. So, before deciding on issues that will have repercussions on the Muslims’ lives in France, the government should form informed decisions requiring active involvement of moderate voices, community representatives and religious authorities. Benchmarking Christianity to make decisions on Islam might not always be the right way of conduct.

The external financing of persons, networks and organizations that conduct activities to result in estrangement and radicalization of French / European nationals (be it migrant descendent or not) should be cut. Individuals, networks and structures that conduct violent acts upon orders from external states should be closely followed and penalized. For this, France and the other MS should have an open eye and they should develop capacity to replace such structures offered/funded by foreign states.

Politicians and people with certain influence diameter should avoid raising rhetoric that can provoke protests and reactions from different faith groups. At a time when the globe is struggling to protect itself from the coronavirus, there is no need to create another artificial crisis that will further cause division and polarization. Unity in solidarity and respect to the others should be valued and extended.

*Onur Sultan is senior research fellow and project coordinator at

Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Endnote

[1]This is the relevant part of the speech by President Macron: “Islam is a religion which is in crisis today, everywhere in the world. We do not see it that in our country, it is a deep crisis which is linked to tensions between fundamentalisms, precisely religious and political projects which, we see in all regions of the world, lead to a very strong hardening , including in countries where Islam is the majority religion. Look at our friend, Tunisia, to cite just one example. 30 years ago the situation was radically different in the application of this religion, the way of living it and the tensions that we live in our society are present in this one which is undoubtedly one of the most educated, developed of the region. There is therefore a crisis of Islam, everywhere which is plagued by these radical forms, by these radical temptations and by an aspiration for a reinvented jihad, which is the destruction of the other. The project of a territorial caliphate against which we fought in the Levant, against which we are fighting in the Sahel, but everywhere, more or less insidious, the most radical forms. This crisis affects us by definition too.”

Bibliography

Barrett, R. (2017). Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees. The Soufan Center.

BBC. (2020, October 31). Nice attack: Grief and anger in France after church stabbings. From BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54745251

Euronews. (2020, October 2). France: Emmanuel Macron presents plan against ‘Islamic seperatism’. Retrieved October, 2020 from https://www.euronews.com/2020/10/02/france-emmanuel-macron-presents-plan-against-islamic-separatism

EUROPOL. (2020). the European Union (EU) Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) 2020. European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation.

France24. (2020, October 21). We will not give up cartoons: Macron in homage to murdered teacher. Retrieved November, 2020 from France24: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20201021-we-will-not-give-up-cartoons-macron-in-homage-to-murdered-teacher

Ganley, E. (2020, November 1). French Muslims, stigmatized by attacks, feel under pressure. Retrieved November, 2020 from Associated Press: https://apnews.com/article/paris-france-emmanuel-macron-islam-europe-ea5e15bb651bbe443b27bc19948cae6b

Hafez, M. (2015). The radicalization puzzle: a theoretical synthesis of empirical approaches to homegrown extremism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 38, 958-975.

Hassan, M. (2014, August 21). What the Jihadists Who Bought ‘Islam For Dummies’ on Amazon Tell Us About Radicalisation. From HuffPost: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/mehdi-hasan/jihadist-radicalisation-islam-for-dummies_b_5697160.html

Jacinto, L. (2017, August 01). France’s ‘deradicalisation gravy train’ runs out of steam. Retrieved February, 2020 from France24: https://www.france24.com/en/20170801-france-jihad-deradicalisation-centre-closes-policy

Katkov, M., & Diaz, J. (2020, November 3). ISIS Claims Credit in Vienna, Austria ‘Terror Attack’. Retrieved November, 2020 from NPR: https://www.npr.org/2020/11/03/930721562/at-least-4-killed-by-gunman-in-vienna-austria-in-terror-attack?t=1604578448415&t=1604670620585

L’Élysée. (2020, October 2). La République en actes : discours du Président de la République sur le thème de la lutte contre les séparatismes. Retrieved October, 2020 from https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/10/02/la-republique-en-actes-discours-du-president-de-la-republique-sur-le-theme-de-la-lutte-contre-les-separatismes

Ojha, S. (2020, October 17). President Macron calls teacher’s beheading in France “Islamist terrorist attack”. Retrieved 2020, October from NewsBytes: https://www.newsbytesapp.com/timeline/world/67524/318727/teacher-beheaded-in-paris-for-showing-prophet-s-caricatures

Pew Research Center. (2016, July 11). Views of Muslims more negative in eastern and southern Europe. Retrieved February, 2019 from Pew Research Center: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2016/07/11/europeans-fear-wave-of-refugees-will-mean-more-terrorism-fewer-jobs/ga_2016-07-11_national_identity-00-01/

Reuters. (2020, September 15). France’s Macron: I won’t condemn cartoons of Prophet Mohammad. Retrieved November, 2020 from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/france-charliehebdo-trial-cartoons-macro-idUSKBN25S672

Salaün, T. (2020, October 17). French police face worst nightmare: an attacker they never saw coming. Retrieved November, 2020 from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-security-attacker-idUSKBN2720NJ

Schwarzenbach, A. (2019). Counter-Radicalisation Strategies: An Analysis of German and French Approaches and Implementations. In B. Akhgar, D. Wells, & J. M. Blanco, Investigating Radicalization Trends: Case Studies in Europe and Asia (pp. 101-122). Springer.

Sozcu. (2020, October 24). Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan’dan Macron’a sert sözler: Tedaviye ihtiyacı var. Retrieved November, 2020 from Sozcu: https://www.sozcu.com.tr/2020/gundem/cumhurbaskani-erdogandan-macrona-sert-sozler-tedaviye-ihtiyaci-var-6096221/

Speckhard, A., & Shajkovci, A. (2018, November 27). Challenges in Creating, Deploying Counter- Narratives to Deter Would-be Terrorists. From Homeland Security Today.us: https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/terrorism-study/perspective-challenges-in-creating-deploying-counter-narratives-to-deter-would-be-terrorists/

Walter, B. F. (2017). The New New Civil Wars. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 469-486.

Walter, B. F. (2017). The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars. International Security, 42(2), 7–39.