|

by Emre Bilgin, Erman Atak, Furkan Akar, Hasan Suzen, Ibrahim Jouhari, Onur Sultan, Saban Yuksel JANUARY 18, 2021 | 18 min read |

Background

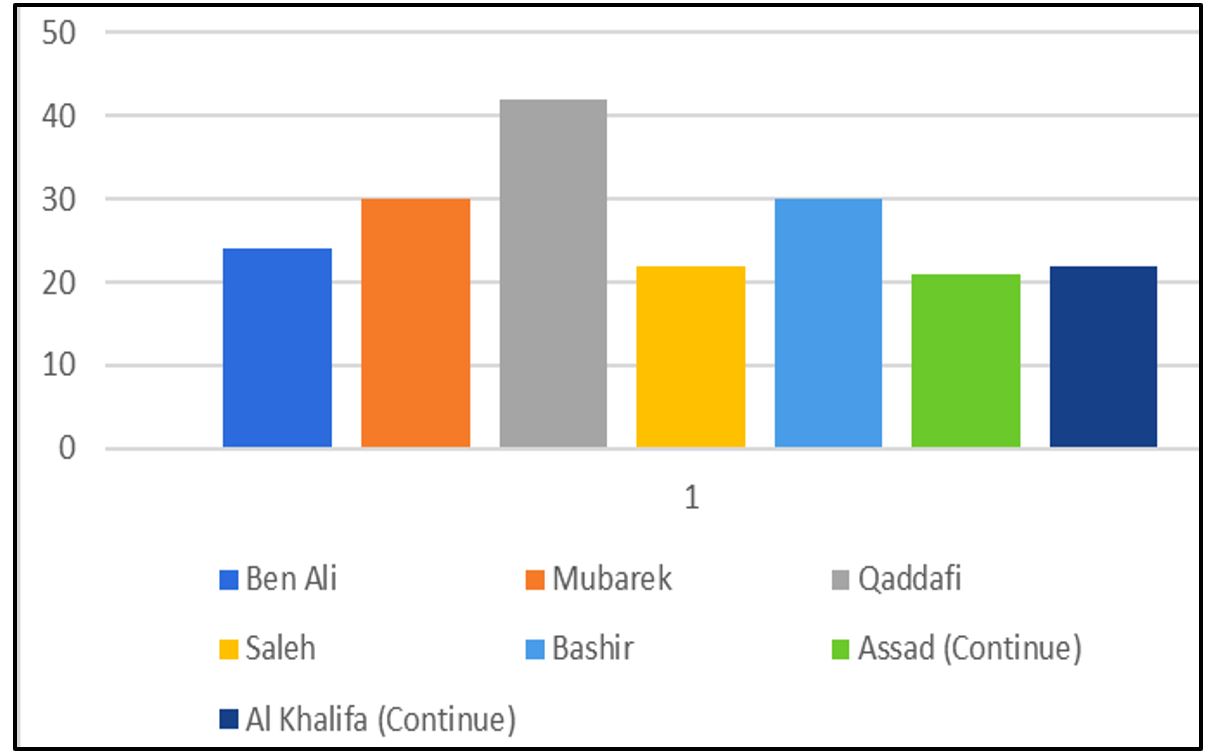

Ten years passed since Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old street vendor, set himself on fire in Tunisia to protest the government, that sparked a massive movement across the MENA region. The movement shook the region’s long-standing authoritarian leaders to the extent that it toppled Tunisia’s Ben Ali, Egypt’s Mubarak, Libya’s Qaddafi, and Yemen’s Saleh.

How many years did they lead?

While Tunisia underwent a relatively peaceful transition into democracy, yet fragile, Libya, Syria and Yemen were torn apart by civil wars, and Egypt dragged into an autocratic regime governed by a former general Al-Sisi. Starting with hopes, the spring has become a winter for the region since the great expectations have faded as fatalities, poverty, unemployment, and poverty have increased.

EGYPT

For Egypt, the Arab Spring was a tumultuous revolution, counter-revolution, violence, and economic hardship, but laced with hope and a positive outlook. That has changed, Egypt is slowly progressing out of the economic slump it suffered during that time, yet economic hardship and problems are still plaguing around 30% of the population. With the still ongoing pandemic, there are fears that economic woes might threaten the 100 million strong country’s fragile stability. Moreover, Biden’s election and the fear that he might choose to take a similar stance as Obama, closer to the popular demands and fostering democracy, is also creating more headaches for the Egyptian rulers.

Data Source: World Bank World Development Indicators

Meanwhile, Turkey’s rise and its enmity to Egypt and the Gulf are putting even more pressure. It is in this regard that once must contemplate the recent rapprochement with Qatar that might indicate that the Gulf at first and possibly followed by Egypt have decided to mend their bridges with Turkey in these uncertain times, to prepare for an uncertain future, with an ongoing pandemic, a new US administration, that might bring further upheavals, stress, and changes.

The Role of the Gulf Countries: For the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and especially Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Arab Spring was a wave of chaos and destruction that they were lucky to evade. Indeed, they even played an important role in slowing it down and making sure that this wave of protests and upheavals did not reach their shores.

They did not only defend their internal stability, but they also actively interfered in several countries undergoing these upheavals, in an effort to shift the outcome to their advantage, in Syria, Libya, and Yemen. The success of these efforts was not very forthcoming. However, the KSA and the UAE were instrumental and successful in countering the Morsi regime after the revolution, helping President Sisi take over. Since then, the GCC countries have funded the President Sisi regime and supporting it economically and politically while forming a regional alliance to maintain the old power structure and counteract rising Turkey’s power and Iran’s expansionist efforts.

Source: Capital

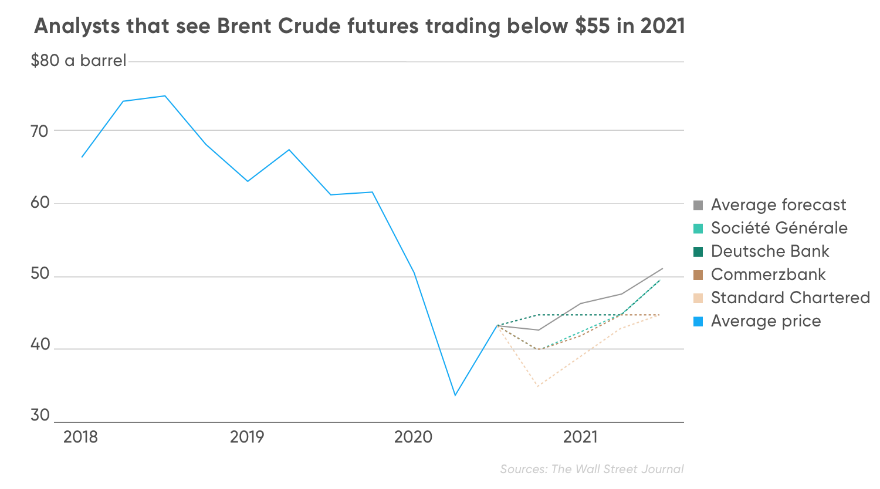

These days, the GCC countries are relatively stable. Despite the low oil prices, they can still offer their population enough to maintain a decent level of prosperity and stability. Nevertheless, the Yemen issue is still creating problems and increasing internal pressure. Meanwhile, the KSA has the looming succession issue, casting some uncertainty on the kingdom’s short and medium-term.

Israel’s role: There are some specific key ramifications of the Arab Spring on Israel’s foreign policy, like domestic politics, relations with the regional actors, the Palestinians and the US, and strategy towards non-state actors such as Hamas, Hezbollah and ISIS. The Arab Spring forced Tel Aviv to rethink its relations with Egypt. Most analysts were primarily concerned with the threat to Israel’s peace and treaties with Egypt and Jordan. Egypt has been one of the most critical pillars of Israel’s national security.

Even during Morsi’s presidency, Israel and Egypt have cooperated on the security issues in the Sinai. Cairo-Tel Aviv ties improved significantly after Morsi’s ouster. Because of the ongoing security cooperation, the relations are at their best. As discussed in the previous brief, to import gas from Israel, Egypt’s stability and prosperity are significant for Israel.

Russia’s Role in Egypt:

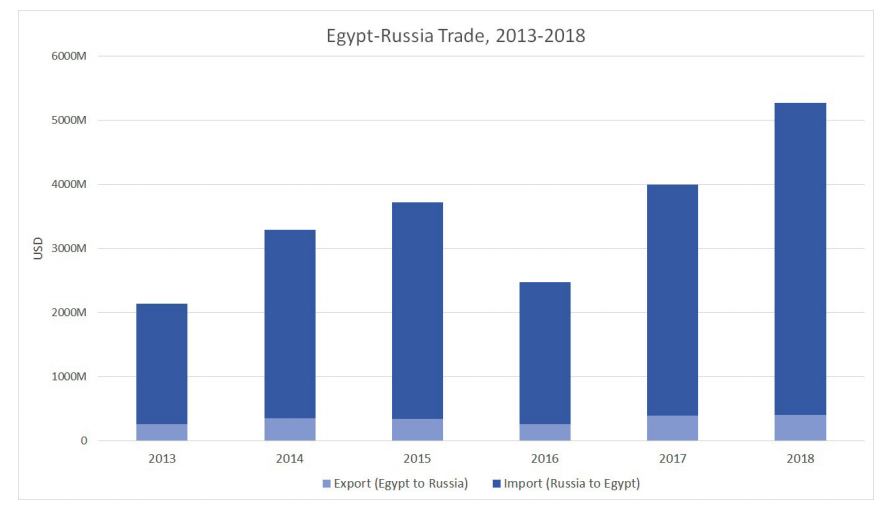

Since the military coup in 2013 which ousted President Mohamed Morsi, Russian-Egyptian relations have been steadily improving. Since then, Putin and current President el-Sisi have been working through military, economic and cultural collaboration to strengthen bilateral ties. Increasing Russo-Egyptian cooperation in the military-technical sector is most evident. Russia has sought expanded access to Egypt’s military infrastructure since President Sisi gained power, and in 2017, the two the Presidents signed an agreement permitting mutual access to the airspace and air bases of each other.

Source: UN Statistics Division

LIBYA

Since the fall of Ghaddafi, Libyans and international actors failed to bring Libya peace, stability and democracy. Both Libyans and western actors, who supported the revolution, decided to leave the transition process to Libyans. Nevertheless, some crucial mistakes, made in the transition process, turned the spring back into winter in Libya.

Libyans failed to initiate a national dialogue process. Rather than a truth-seeking and transitional justice approach, collective revenge culture took over. Political isolation law pushed all Ghaddafi-era well educated and seasoned intellectuals out of the equation. Rather than an institutional reform, armed militias put on to government payroll, which empowered militia groups and brought together a militia control over Libya’s resources.

In this atmosphere, Libya went to elections two times: in 2012 and 2014 when the political Islamists lost their advantageous position and did not admit the results. The newly elected parliament rather than Tripoli gathered in Tobruk, which initiated its current divided form. To solve the problems parties came together in Skhirat/Morocco at the end of 2015, resulted in the establishment of the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) in early 2016, but could not reunify the country.

Power vacuum in the country attracted many terrorist groups to the country. ISIS control over Sirte region in 2015 and 2016 was the peak for terrorist intervention to Libya. Now terror groups are spread to deserts of Libya rather than littoral parts of the country.

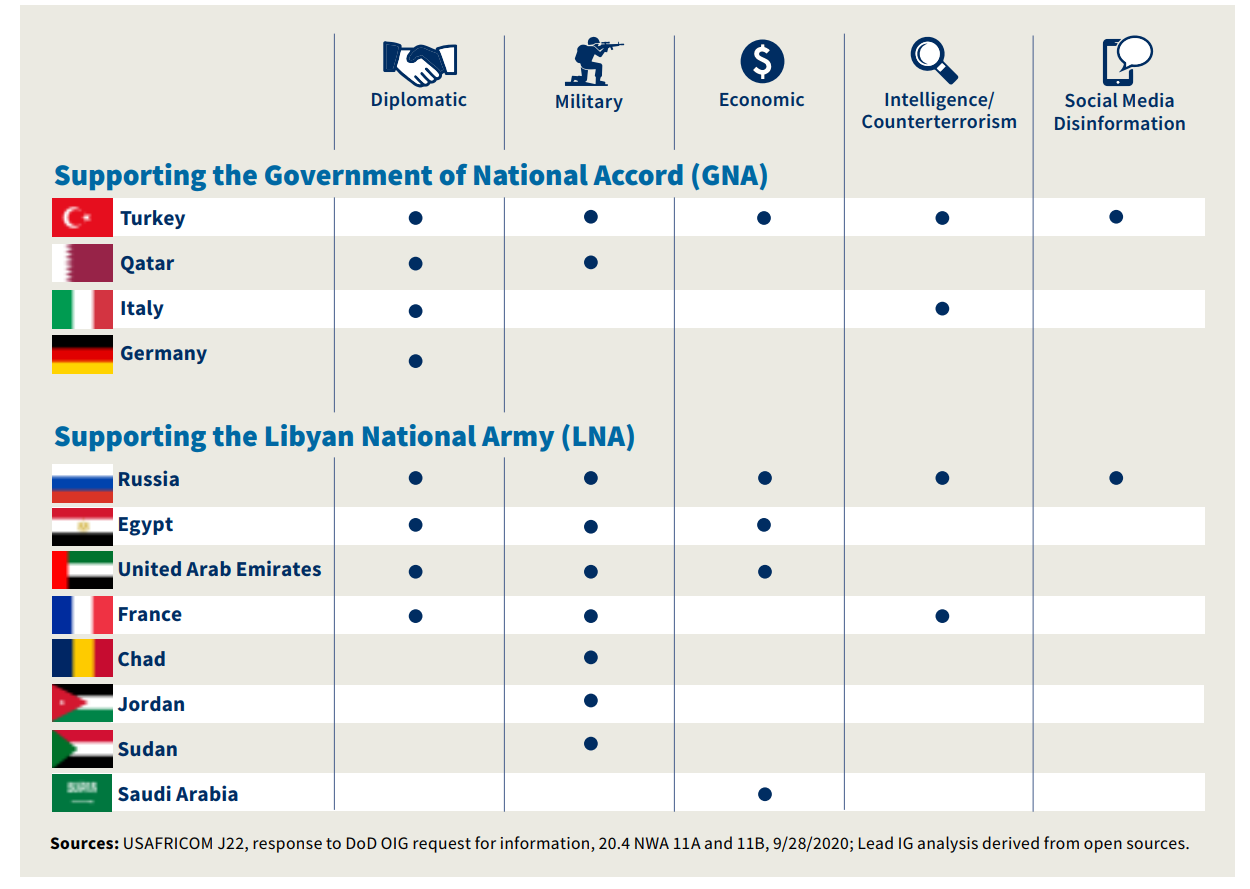

Source : US Department of Defence

Khalifa Haftar’s offensive on Tripoli in April 2019 was another turning point for Libya. Upending an UN-sponsored political negotiation process, Haftar, backed by UAE and France —Russia and Egypt, also supported Haftar, but not his offensive— attacked on Tripoli to terminate the UN-recognised GNA. Last turning point was the deals on maritime boundaries and military cooperation between Serraj and Turkey’s Erdogan in November 2019, and developments following these agreements. Being left all alone by the western actors against Haftar, Serraj was pressed up to the point of signing maritime agreements with Turkey.

Following the deal, Ankara and Moscow gained the possession of Libya dossier. The agreement between the two initiated a new ceasefire process, which was rejected by Haftar in early 2020. Russia punished Haftar by pulling its mercenaries from western Libya to Jufra region in central Libya. Soon afterwards, LNA defeated and reunited with Russians at Sirte-Jufra front, where they managed to stop the GNA. However, Haftar lost some traction now. His external backers are looking for a more reliable actor in eastern Libya.

Military stalemate provided the UN with a new round of ceasefire and political negotiation process, both of which obstructed now. The risk of a reignition of an armed conflict is relatively high, and Libyan factions and their external backers have sustained their military build-up. More than 20.000 foreign fighters (according to UN envoy) are still waiting for their next battle inside Libya. Tripoli government is under militia control, and Libyans are far from reaching a compromise solution.

Libya is a rich country with great potential and a small population. If they find peace and stability and establish democratic governance at some point, it would be the Dubai of North Africa. A resource-rich country, which can save Europe from being dependent on Russian resources, is an attraction point for the migrants not an embarkation point to Europe.

Russia’s Role: Bilateral relations between Russia and Libya were neither close nor indifferent prior to the Arab Spring. Instead, the Russians saw Libya as a location for their energy interests to be promoted, arms sold, and Western superiority over the Mediterranean challenged. Moscow supported all opposition parties, such as General Haftar and Mr Serraj, during the civil war. Libya plays a crucial role in the Transit Route of Africa.

Russia’s policy seems realistic and reasonably balanced. Economic interests seem to be dominating Russia’s agenda. According to several reports, if Moscow supports Haftar, he has agreed to renew Qadhafi’s main contracts with Russia. Given Russia’s aspirations for greater power in the Middle East, it might theoretically benefit from acquiring a permanent naval facility on the Libyan coast, like Syria.

SYRIA

The Arab Spring could never reach Syria. The unrest that started in March 2011 in Dara had quickly triggered a civil war entering its tenth year. The economy is in collapse, and the country’s more than half of its pre-war population is either a refugee or an internally displaced people (IDP). There will be a Presidential election planned for spring 2021, which will be nothing more than a symbolic election and will not change Assad’s problematic rule.

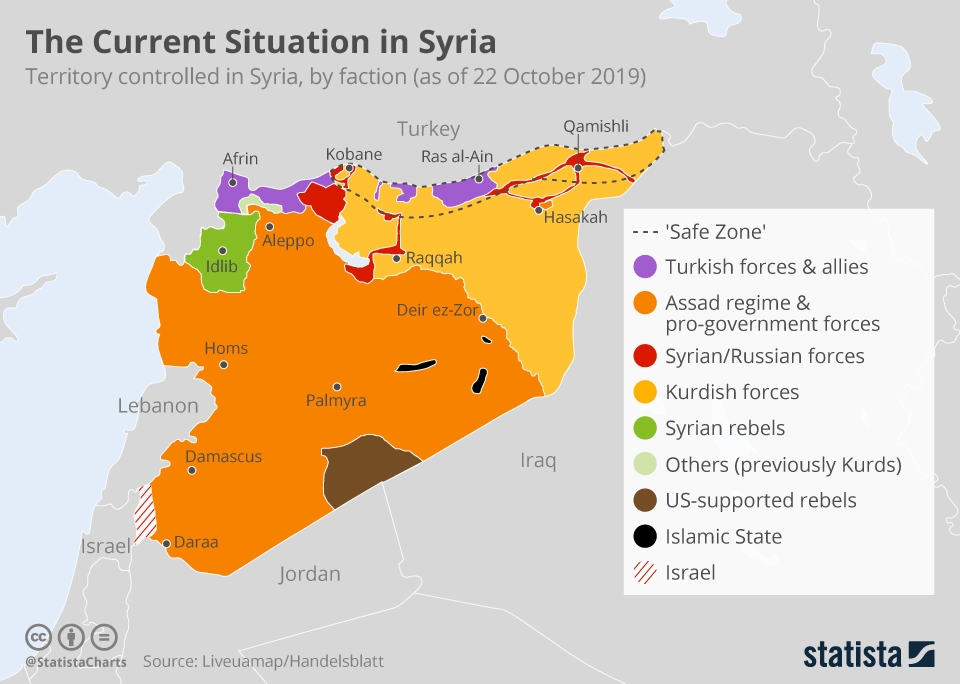

Source : Statista

Since the Turkey-Russia ceasefire in March 2020, the battlefronts in Syria are relatively calm, with sporadic shelling and attacks on enemy positions in the Idlib province as well as in the east of the Euphrates. There are two peacebuilding processes underway; the first one is Geneva negotiations led by the UN and the second one is Astana negotiations, led by the trio of Iran, Russia and Turkey. The former leads the efforts to write a new constitution while the latter prioritises achieving ceasefires. In 2021, more efforts are needed to integrate these two separate processes in order to show promise to peacebuilding efforts.

The most problematic issue in Syria after a decade of civil war is the economy. Deteriorated with the CEASAR sanctions imposed by the US, the Syrian per-capita decreased from nearly 2300 dollar in 2012 to 230 dollar in 2020. There is an enormous shortage in bread and oil, and the estimated budget deficit will likely hamper reconstruction efforts of the regime. In short, without any relief in the sanctions, 2021 will be economically devastating for Syria.

Russia’s role in Syria: Under the Putin regime, Russia’s actions in Syria are emblematic of strategic dependence on hard power and coercive diplomacy, and have provided Kremlin with a military foothold to form the balance of power in the Middle East. Gaining military prominence in Syria has had significant advantages for Moscow; the Russian military has a starting point from which to project military power in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea by setting up permanent military bases. Other countries in the Middle East have also been encouraged by Russia’s perceived success in Syria to seek improved relations with Moscow amid the US pivot out of the region. In recent years, the leaders of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Egypt, the Iraqi Kurdistan Region, Sudan, and Israel have all paid visits to Moscow.

The Syrian war has also boosted Russia’s mercenary sector, particularly the Wagner group associated with Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman known as “Putin’s chef” for catering at events attended by the President of Russia. There have been accounts of Wagner mercenaries operating in Venezuela, Mozambique, Madagascar, the Central African Republic, Libya, and elsewhere.

YEMEN

The widespread protests against President Ali Abdullah Saleh starting as early as January 2011 called for leaving the seat he occupied in the last 33 years. On 23 November 2011, he had no choice but to sign GCC peace and power transfer agreement that foresaw transfer of his powers to Vice President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and formation a unity government that would hold presidential elections.

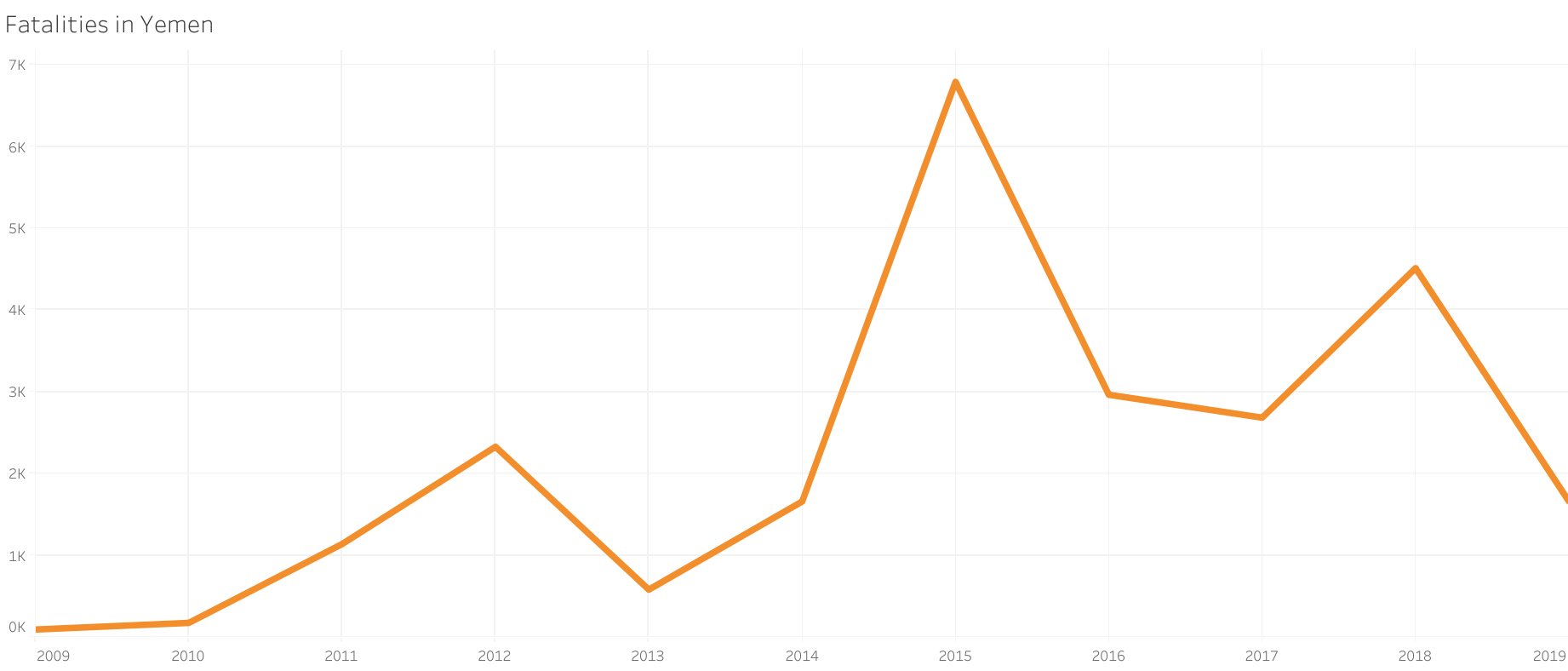

Source: Data from the UCDP

Immediately after becoming president, Hadi announced the presidential election would be held on February 2012. Houthis announced to be ready to join the political race with newly established Al-Omah party tasked by them to further the cause of “independence from foreign domination”. Southern secessionists made calls to boycott the elections. Hadi won the elections by getting 99% of the votes. He had to redress the broken economy and the statecraft, provide security and services, and reach out to separatists in South and North.

Saleh, who was forced to resign, joined Houthis to set Yemen on fire in the last 6+ years. The civil war started with Houthis wresting control of Sana’a in September 2011 saw Coalition forces belonging to mainly Saudi Arabia and the UAE intervene against Houthi forces. That turned Yemen a field of a protracted proxy war between Iran and its competitor Gulf Countries since President Hadi came to power, he has never been able to progress in the initial three areas he defined to redress. The war has also generated 4 million internally displaced persons uprooted from their lands.

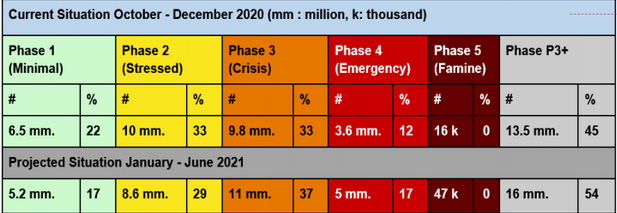

The UN’s Integrated Food Insecurity (IPC) Phase Classification initiative that provides rigorous, evidence- and consensus-based analysis of food insecurity and acute malnutrition situations worldwide show 45% of 30 million Yemenis live IPC Phase 3+ conditions, which mean a high level of food insecurity. The report further illustrates the deterioration by estimating that this figure will go up to 54% under the same conditions. The majority of those living in IPC 4/5 levels are in the Houthis-controlled-areas.

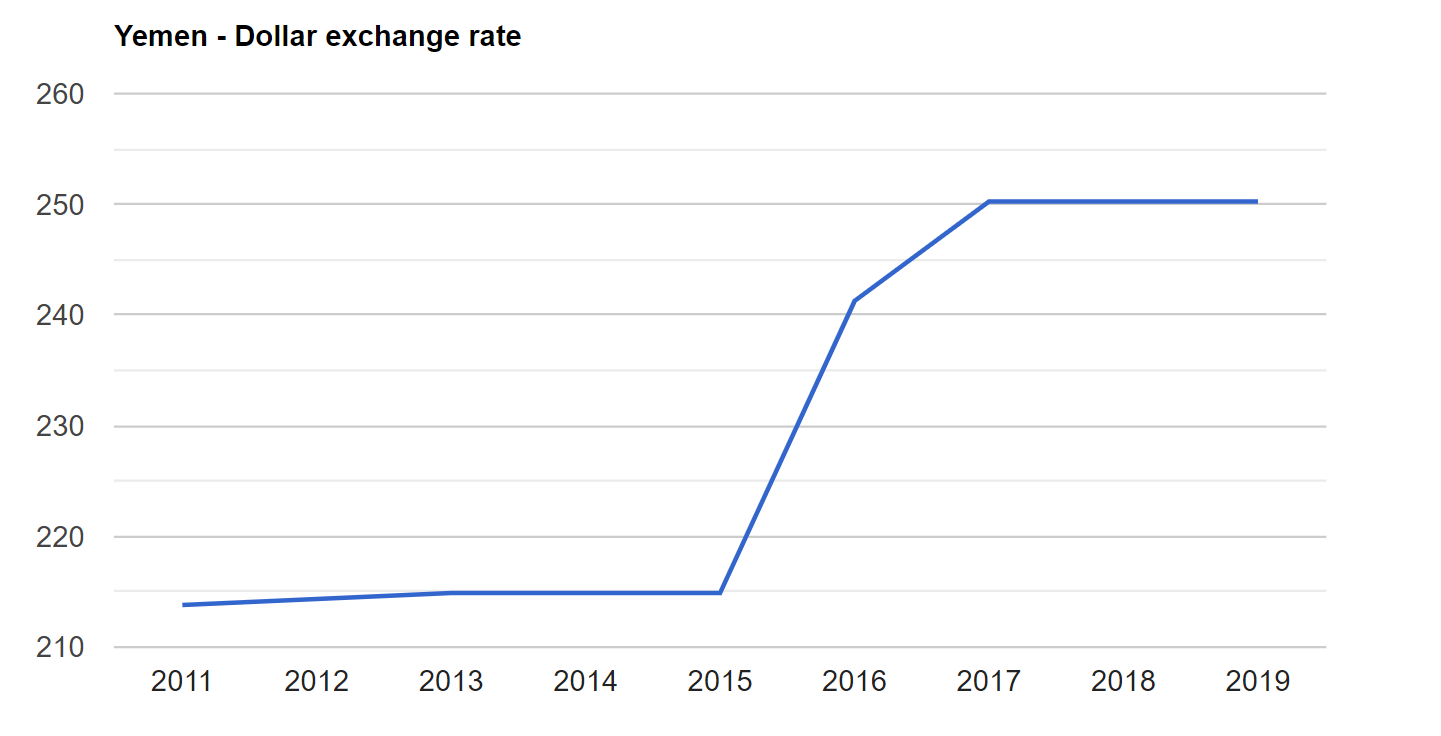

Another issue that Yemen has to deal with is the volatility of the Yemeni Riyal. 80 to 90% of the staple food, medicines and fuel are imported in Yemen, any depreciation therefore directly translates into inflation and lower purchasing power. The YER/USD ratio increased from 215 to 250 after the eruption of civil war. Due to mainly depletion of foreign reserves, Central Bank of Yemen decided to float the YER in August 2017 that causes 40% value loss. The exchange rate plummeted in October 2018 to even 800 YER/USD. It spiked to 590 YER/USD in March and 600 YER/USD in August 2019. At the end of 2020, the Yemeni Riyal collapsed, exchange rate reaching the rate of 880 YER/USD.

Source: The Global Economy

Israel’s policy against Yemen: Preventing the Iran-backed Houthis from growing more powerful and acquiring advanced weapons from Tehran is the primary interest of Israel in Yemen. The policy of the coalition – led by Saudi Arabia, overlaps with Israeli interests. Not only the Saudi-backed Hadi government but also UAE-backed southern forces serve Israeli foreign policy in that arena. The Southern Transitional Council (STC) aims for independence for South Yemen, which could safeguard Israel’s interests. For Israel in particular, the rise of the STC could be a positive development given the organisation’s apparent openness to Jews. Although the STC has neither capability nor infrastructure to provide essential services, it could be one of the means to ensure Israeli interests.

EUROPEAN UNION

The EU has engaged with North African countries to promote democracy, the rule of law and respect on human rights from 2003 on. Though the EU has long-waited democratisation of the region, it could not pursue a common policy and thus a seamless action while the EU member states favour conflicting power centres, those in line with their interests. This has worsened an already dire situation, tumbling down a vicious cycle of destabilisation, increased the migration flow to the EU, rising of far-right and thus tightening migration policies.

To give a flavour of conflicting interests, while France is supporting Haftar’s LNA along with Russia and Saudi Arabia, Italy and Germany favour the GNA supported by Ankara. This crack hinders a common policy towards Libya and Turkey. Moreover, while the EU is reluctant to act, the policy of external actors present exponential impact upon the Union.

Apart from divergence within the Union, the Member States act in contrast to the general European interests and values, mostly appeasing ‘new dictators’ of the region. For instance, Berlin permitted sale of arms and military equipment worth €752 mm. to Egypt, €305 mm. to Qatar, 5 mm. to UAE, 23 mm. to Kuwait and 22 mm. to Turkey, all of whom involved in the conflicts. On the other hand, France awarded Egypt’s new dictator al-Sisi, the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour in an official visit to Paris, a move sparked outrage, not only from the human rights activists but also from ex-recipients of the award, returning theirs in protest.

Strategic Foresight

Based on the analyses above, it is highly likely that:

- Starting with great hopes, the spring turned into a winter in which the region’s financial and democratic situation exacerbated much more than pre-revolution period. Given damages inflicted pandemic, and the divided international community, it will take years to turn back to pre-revolution conditions if not become worse.

- The movements were believed to turn the tide in the Arab world towards a more European way as they will strive for more rights, freedom and democracy. However, countries drift away from the from Europe, enter into Russia’s orbit.

- The upheavals stressed the separation of Russia’s status from Western countries and set the stage for increasingly different foreign policies and power rivalry. Russia hopes to regain a foothold in Middle Eastern countries by using a blend of economic and public diplomacy, capitalising on the increasing distrust of Western motives by the regional population.

- Although the West saw the demonstrations as a shift towards democratic change in the Western model, it was seen by Russian observers at the time as a return to the traditional values of Middle Eastern societies, incorporating more Islamic identity. In short, Islamization over democratisation was emphasised as the key motivator in the Russian perception of the Arab Spring.

- The Syrian case highlights the need for hard power to restore Russian hegemony in the Middle East, but it is unnecessary to preserve it in countries other than Syria. For this reason, as is evident from its approaches to other regional states, such as Turkey and Egypt, the Kremlin has turned to soft power.

- The recent rapprochement with Qatar that might indicate that the Gulf at first and possibly followed by Egypt has decided to mend their bridges with Turkey in these uncertain times, in an effort to prepare for an uncertain future, with an ongoing pandemic, a new US administration, that might bring a lot of further upheavals, stress, and changes.