NATO-Turkey Relations in a Turbulent Environment: The Military Dimension of NATO-Turkey Relations

|

by Samet Coban*, Furkan Akar** DECEMBER 2020 | 12 min read |

For understanding NATO-Turkey relations: “…You can just look at the map.”

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg [1]

1. Background: Changing NATO-Turkey Relations

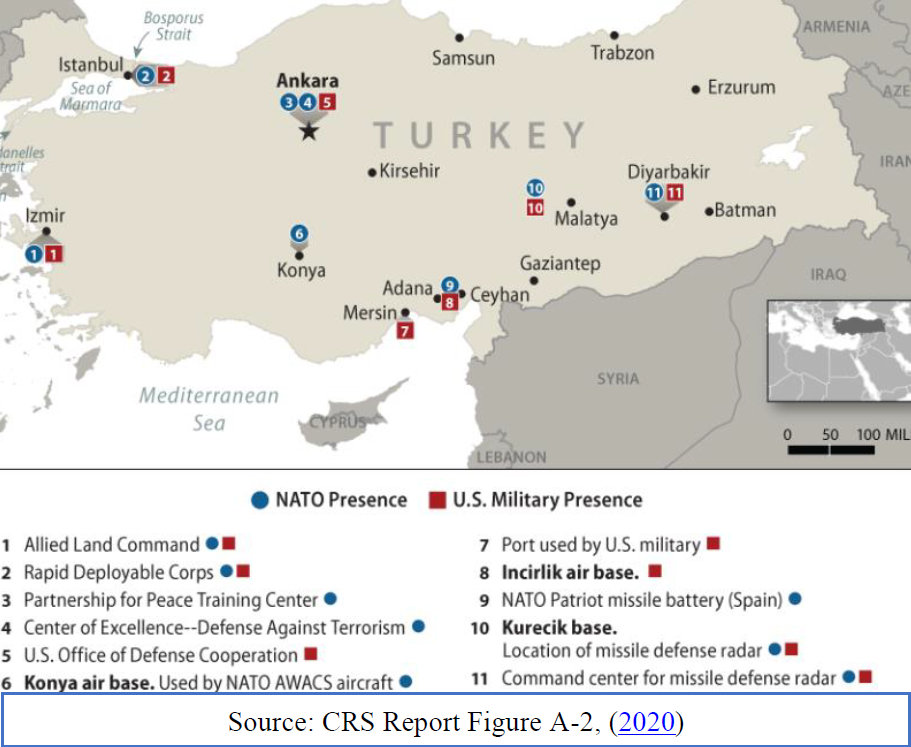

Looking at a map is a very traditional but illuminating embarking point upon an analysis regarding NATO-Turkey relationship and its relevance since geography is a constant variable imposing substantial restrictions on devising a strategy and policymaking. In this vein, situated in a location connecting three continents in the Middle East and being the patron of Turkish Straits, and the South-eastern flank of the Alliance, Turkey, has been regarded as an indispensable part of NATO.

Contained by Russia around its borders, exacerbating relations with Armenia, Iran and Syria, Gulf States – despite the recent rapprochement with Saudi Arabia – most of which are exposed to the surging Russian influence, Turkey lives in a very fragile region. Hence, NATO provides a crucial anchor and a security guarantee for Turkey to maintain its stability, security and well-being in its land and around the borders as well in the Middle East.[2]

On the other side, as James Jeffrey points out “In the Post–Cold War mess…almost all our conflicts you pick one Georgia, Ukraine, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iran nukes, Syria, Gaza. They all involved Turkey, and we could not have done the things we did if Turkey were uncooperative or opposed to it—it‘s that simple.“[3] A Turkey assuming responsibility in the Euro-Atlantic security architecture is of everybody‘s interest and a win-win situation for both sides. All other options come with hefty prices for both parties.

In recent years, Turkey‘s increasingly ambitious and assertive policies have differed from its allies, e.g. YPG, S-400, and the Eastern Mediterranean.[4] The country is backsliding from democracy, experiencing a ‘remarkable rapprochement‘ with Russia[5] and the current administration is posing a challenge to NATO from within.[6] Discord between allies is not new, yet the US pullback and domestic dynamics of Turkey exacerbated the intensity and the extent of disputes making it harder to contain them within NATO.[7]

In this context, policy-makers and scholars think whether Turkey comes to a crossroads. Some authors and politicians even contend that the time to expel Turkey from NATO has come, though no mechanism exists as such.[8] Most analysis in this respect cannot go beyond wishful thinking and cannot answer “so what“ question. Before removing any member from the Alliance, it has to be taken into account the technical dimension of the relations, e.g. relocation of NATO/US Assets in Turkey, military (dis)integration with Turkey, and takeover of Turkish Armed Forces‘ role in the Alliance. Furthermore, if this happens, how to address the disputes with a Turkey outside of NATO is still unclear.

In this context, policy-makers and scholars think whether Turkey comes to a crossroads. Some authors and politicians even contend that the time to expel Turkey from NATO has come, though no mechanism exists as such.[8] Most analysis in this respect cannot go beyond wishful thinking and cannot answer “so what“ question. Before removing any member from the Alliance, it has to be taken into account the technical dimension of the relations, e.g. relocation of NATO/US Assets in Turkey, military (dis)integration with Turkey, and takeover of Turkish Armed Forces‘ role in the Alliance. Furthermore, if this happens, how to address the disputes with a Turkey outside of NATO is still unclear.

The sui generis power-sharing structure within the Turkish State, even though substantially changed under the current Turkish government, puts Turkish Armed Forces (TAF), arguably the most integrated institution of the Republic with the West, in an exceptional place where it can tip the delicate balance between Turkey and its allies. The literature on the relationship between Turkey and NATO, a politico-military alliance, has surged lately; whereas, the technical/military dimension of it is still understudied. Most of the analysis is heavily based on the consolidated domestic power of the Turkish President and his preferences with respect to Turkish foreign policy, and the Alliance as such. Nevertheless, even if the Turkish President is (or becomes) ambitious about leaving NATO, disintegration and departure from the Alliance are much more challenging than many analysts think.

In this paper, we therefore aim to grasp the factors that make NATO relevant for Turkey, particularly in terms of military dimension. We believe that less is comprehended on the technicalities of Turkey‘s membership in the context of TAF, that prevents a healthy understanding of NATO‘s role for Turkey‘s security and defence, and vice versa.

2. Political Landscape

While there are proponents of a harsh response against Turkey and hardliners in Turkey against NATO, not all experts think in the same way,[9] and this is not resonated among all leaders. NATO and Turkish leaders frequently confirmed their commitments publicly. NATO Secretary General reiterated that Turkey is a valued/key ally and “it [Turkey‘s removal] is not a question“. Moreover, most frequent words NATO Chief uses with Turkey are “key ally, valued/valuable ally, and fighting terrorism. [10]

According to Turkish MFA, there seems no change about Turkey‘s commitments given to NATO.[11] Turkish Defence Minister stated that “The Alliance enjoys good health. It is not experiencing a brain death.“ referring to Mr. Macron. Turkish President points out that “The relationships [of] Turkey … with different countries and regions are not alternatives to each other, they are complementary. Because of the S-400 … to speculate about our tendency is not to grasp us, our history and geographic location (highlighted).[12] Even, the Chairman of the Foreign Policy and Defence Council of Russia asserts that “No one in Russia expects Turkey to leave NATO“.[13]

3. From Political Landscape to Military Means

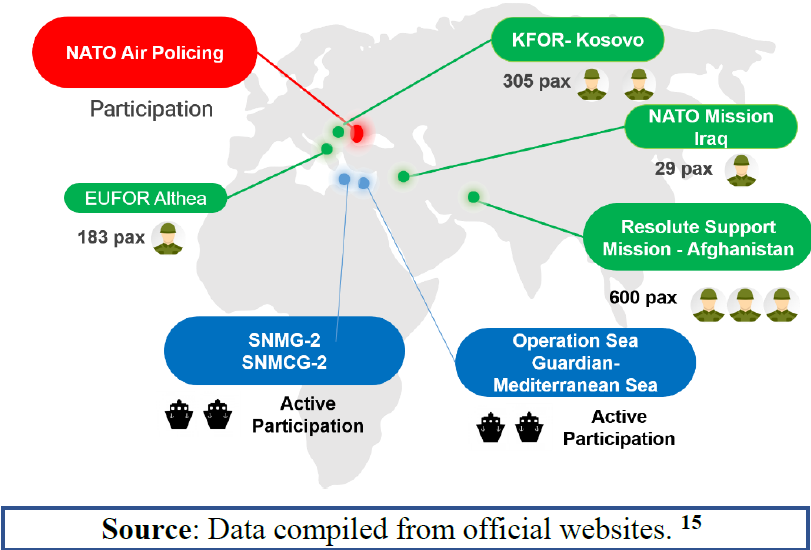

Unlike political turmoil, military relations between Turkey and NATO are on track. What most analysts agree about is that there is no shrinkage of Turkish military contribution to NATO. Turkey (still) provides substantial contributions to the NATO and EU-led operations. As Flanagan and Wilson point out “engagement slowed somewhat in the immediate months after the coup, almost 95 per cent of planned operations and activities with US Army Europe forces resumed the following year. In fact, the TSK [TAF] participated in ten US Army Europe exercises during 2016, which was a significant increase over previous years.“ [14]

Along with these operations, Turkey contributes to the NATO Response Force (NRF) substantially, e.g. hosting an NRDC Headquarters in Istanbul and providing naval vessels to SNMG-2 and SNMCMG-2 that are maritime components of the NRF.

More importantly, Turkey will resume the command of NATO‘s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), the spearhead force of the NRF in 2021 and is expected to assign additional military headquarters regarding NATO Readiness Initiative (NRI).[16]

The active participation of Turkey is incoherent with harsh rhetoric of both sides. In case, a Turkey, which is pivoting to the East, is expected to diminish its contributions. Why doesn‘t Turkey decouple from NATO at least to some extent? Conversely, cooperation is still increasing amidst tensions. For example, the Maritime Security Centre of Excellence was accredited by NATO in June 2020.[17]

Turkish Armed Forces is amalgamated with NATO. Its broad participation necessitates a deeper integration, i.e. interoperability and capacity to conduct exercises, campaigns together with the other members of the Alliance. Almost all Turkish assets, whether they are made indigenously or exported, are produced according to NATO standards and contain critical components that are imported from Western allies. Moreover, maintenance and operating procedures, spare parts, technical manuals, field manuals, signals, messaging standards are generated and maintained as such, that requires a specific training and foreign language, i.e. English, know-how, all of which takes a long time to acquire.

NATO countries are Turkey‘s most critical foreign arms suppliers. Turkey imported/ordered all primary weapons from NATO countries between 2016-2019 except for a training aircraft from Pakistan and S-400 system, that is an extraordinary one with a top-down order as Egeli points out.[18] For instance, Turkey is the number one customer for the German defence industry, accounting one-third of German arms exports.[19]

Substantial Turkish commitments to NATO entities as well as the active participation of TAF to the NATO missions and operations contradict with the Turkish government‘s (domestic) political discourse and hardliners in the Western community. This continuation indicates that traditional tendencies are still in place when it comes to defence and security priorities.

4. Where Does Turkish Armed Forces Stand Among Other NATO Armies?

Graph-1:

Defence Expenditure as a share of GDP (x) and Equipment Expenditure as a share of Defence Expenditure (y)[20]

The scatter plot shows two NATO defence spending benchmarks, namely, Defence Expenditure share in GDP (a.k.a. the “gold standard“ as Trump administration’s top national security officials put it) and Equipment Expenditure share in Defence Expenditure. 2020 estimates show that Turkey will spend 1.91% of its GDP (better than half of its NATO Allies) for its defence and 36.9% of this money will go to equipment (the 2nd best NATO Army, slightly behind Luxembourg).

Using the Defence Expenditure data and military personnel numbers from NATO (2020 estimates)[21], we created the following graphs to contextualize and understand Turkey‘s place in NATO.[22]

Graph-2:

Defence Expenditure Comparison among NATO countries

According to 2020 estimates, Turkey spends roughly USD 18 bn, which is 1.75 per cent of NATO Allies’ overall defence spending, that constitutes the 7th defence budget in NATO (5th in NATO Europe).

Graph-3:

Comparison of NATO Allies’ defence spending concerning their geography.

Studying defence spending reflexes of countries irrespective of their geography leads to misinterpretations. The map shows that eastern Allies that are close to various “threats,“ i.e. their proximity spend (proportionally) more on defence. In a NATO without Turkey, the defence burden on the shoulders of the south-eastern flank of the Alliance may increase significantly. On the other hand, defending a Turkey outside of NATO will be very challenging if not impossible.

Graph-4:

Defence Expenditure Balance- NATO Europe vs NATO North America

When we look at the defence expenditure balance between two sides of the Atlantic, money was spent on defence in North America tripled Europe almost throughout the last decade. Kicking out Turkey from the equation will only exacerbate the disparity against continental Europe (presumably in favour of Russia).

Graph-5:

Military Personnel Figures of NATO Allies

To grasp what Turkey really means for NATO, one should look at military personnel figures as well. Turkey has the second–largest army of the Alliance, which has more manpower than the entire armed forces of 20 Allies. No NATO country can therefore compensate Turkey‘s withdrawal in terms of military staff

Consequently, NATO is a very crucial anchor for Turkey‘s security and well-being, and Turkey is an essential partner for the transatlantic Alliance, contributing to the security of the EU and the region surrounding the country as well, despite toxic political debates.

Conclusion and Recommendations

NATO-Turkey relations are experiencing a turbulent time due to several factors. Nevertheless, there is no substantial change or transformation in the technical/military dimension of the relations. Four reasons can explain the current situation.

- Strategic orientations cannot change overnight, even though some leaders strive for it.

- Conceptual/doctrinal and technical integration with NATO is so powerful to the extent that makes decoupling very challenging if not possible.

- Living in a fragile region, the cost of maintaining the territorial integrity of Turkey contained by Russia around borders without NATO is incomparably high.

- The identity/mindset of Turkish defence community (ideational aspect) is still Western-oriented. Yet, pro-Erdogan and Eurosianist groups are trying to consolidate their gains in post-15 July Turkish army.

As depicted in this paper, despite strains, Turkey continues to be a member of NATO. The proponents of expelling Turkey from NATO have a slim chance, and it is too dangerous for both sides. Thus, there is no benefit in using this narrative. Instead, the problems and disputes should be discussed to find common ground and to set sail for new alternatives for cooperation. As the latest report, which is the outcome of reflection process points out, having robust militaries and the state of art warfighting capabilities are not sufficient in today‘s world. At the same time, the Alliance should also be politically coherent and robust. [23] Resolving crisis with Ankara is not only about handling issues with Turkey, but it is also a manifestation of NATO‘s capacity to unravel problems and maintaining political unity even under the stormy weathers.

To this end, our recommendations are as follows:

- In order to remain politically coherent;

-

- NATO should continue to use the de-escalation mechanism actively and effectively to prevent a conflict at sea and establish several mechanisms through which allies can discuss their problems (including agree to disagree on some issues).

-

- The NATO Secretary–General should task a group of experts (officially appointed experts if possible) from both sides to argue the current disputes and possible solutions which can be offered to allies, particularly to Greece and Turkey. The expert group can at least find the convergence/divergences among allies in a written report.

- Allies should show that they grasp Turkey‘s concerns and complaints, particularly in terms of YPG in Syria, and maritime delimitation issues in the Eastern Mediterranean.

- The NATO Secretary–General should task a group of experts (officially appointed experts if possible) from both sides to argue the current disputes and possible solutions which can be offered to allies, particularly to Greece and Turkey. The expert group can at least find the convergence/divergences among allies in a written report.

-

- They should also manifest their concerns and illustrate the red lines of NATO once again and remind Ankara that NATO‘s security guarantees do not have to be taken for granted, which is essential for a Turkey located in a fragile region.

- Turkey should understand that disunity within the Alliance has a hefty price for both sides, especially in an environment in which Turkey is surrounded by Russia.

- Turkey should avoid inciting transatlantic peers by pursuing an overambitious policy and using a harsh discourse for domestic politics.

- It might be enlightening for Turkish foreign policy and defence planning practitioners to recall post–WWII circumstances which dictated Turkey certain geostrategic choices and which are still relevant.

Every ally has responsibilities to keep NATO up and running for ensuring its security considering the diminishing stability in the world and the fragility of NATO‘s South-eastern Flank. In any case, keeping strategic patience is more valuable for both sides than burning the bridges.

For grasping it, “You can just look at the map.“

* Samet Coban is a Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon ISSG

** Furkan Akar is a Research Intern at Beyond the Horizon ISSG

[1] Remarks by President Trump and NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg, London, (2019)

[2] S.Ulgen, Turkey is Learning Why NATO Membership Matters, Bloomberg Opinion, (2020)

[3] J. Jeffrey, Turkey and the Failed Coup One Year Later, (2017) The Washington Institute, 42:30

[4] J. Zanotti and C.Thomas, “Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations In Brief”, CRS. (2020)

[5] M. Reynolds, Turkey and Russia: A Remarkable Rapprochement, The War on the Rocks (2019)

[6] M. Pierini, How Far Can Turkey Challenge NATO and the EU in 2020?, Carnegie Europe, (2020)

[7] C. Major, `Catalyst or crisis? COVID-19 and European Security`, 17 October 2020, NDC Policy Brief.

[8] ‘Throw Turkey out of NATO’, (2019); ‘Erdogan’s Gone Too Far. It’s Time to Throw Turkey out of NATO’, (2019); ‘It’s Time to Expel Turkey from the Western Alliance, (2019); ‘Time to Kick the Islamizing Turkey Out of NATO’,(2019); S.Ulgen, ` Turkey is Learning Why NATO Membership Matters`, Bloomberg, (2020)

[9] P. Pry, ‘Expelling Turkey from NATO Would Create a Dangerous Foe’ The Hill, (2019); R. Ellehuus, `Turkey and NATO: A Relationship Worth Saving`, (2019); J. Stavridis, ‘Kicking Turkey Out of NATO Would Be a Gift to Putin’, (2019); J. Dempsey, ‘Judy Asks: Is Turkey Weakening NATO? – Carnegie Europe, (2017).

[10] Remarks by Secretary General (2019); Turkish Foreign Minister (2020); `Turkey is a valuable NATO ally.`(2020); Interview with NATO Secretary General, NTV (2019); Adapting NATO for 2030 and beyond, (2020)

[11] Turkey’s and NATO’s views on current issues of the Alliance, Turkish MFA

[12] ‘Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan’dan S-400 Açıklaması’ (S-400 statement from President Erdogan) (2020)

[13] M. Saglam, `Nobody in Russia expects Turkey to leave NATO`, Gazete Duvar, (2020)

[14] S. J. Flanagan and P. A. Wilson, “Implications for the U.S.-Turkish Partnership and the U.S. Army”, RAND. (2020)

[15] Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures, (2020); KFOR Contributing Nations, (2020); Turkish Troops in Iraq, TAF General Staff; For Turkish Assets in the Operation Sea Guardian, see NATO Media Centre; Turkey’s recent participation to NATO Air Policing, NATO-AIRCOM; EUFOR Althea uses NATO resources within the scope of Berlin-Plus Agreement (SHAPE): [1] This is an overview and not a complete or exhaustive list since not all numbers are available in open sources such as the number of staff in Mons, Brussels, or Northwood Headquarters, and so forth.

[16] M. Yetkin, ‘Turkey Prepares for More Roles in NATO’, Atlantic Council, (2018)

[17] Maritime Security Centre of Excellence, `Who we are`, (2020)

[18] For Turkey’s arms imports SIPRI Arms Trade; For Turkey’s major arms transfers SIPRI Trade Register;

S.Egeli, ‘Making Sense of Turkey’s Air and Missile Defense Merry-Go-Round’, All Azimuth, 8.1 (2019).

[19] ‘More Than One Third of German Military Exports Go To Turkey`, Greek Reporter Europe (2020)

[20] PR/CP (2020)104, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2020)

[21] Ibid.

[22] You can access the original tableau files in which you can select different years via this link.

[23] Adapting NATO for 2030 and beyond, (2020). There are some brave proposals in the reflection group report addressing problems faced within the alliance. It is highly likely that some of these proposals will inform the next NATO Strategic Concept.

NATO-Turkey Relations Policy Brief-Beyond the Horizon ISSG

NATO-Turkey Relations Policy Brief-Beyond the Horizon ISSG