Key Takeaways

- China’s institutional push: Xi Jinping placed finance at the heart of the SCO’s future, reviving the idea of an SCO development bank, pledging aid and loans, and promoting local-currency trade. His goal is to give the bloc practical economic weight while reducing reliance on Western financial systems.

- India–China pragmatism: The Xi–Modi meeting marked the most meaningful contact since the 2020 Galwan clashes. While no breakthroughs were announced, both leaders signaled intent to manage tensions and cooperate selectively, underscoring a fragile but pragmatic thaw.

- Russia’s diplomatic signaling: Vladimir Putin used the platform to project momentum on Ukraine by referencing new “understandings” with Washington. The SCO offered Moscow one of the few international stages where it appeared embraced rather than isolated—though its influence remains constrained by war and sanctions.

- Central Asia’s balancing act: For Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, the SCO is both a source of opportunity and a hedge. They welcome infrastructure and energy projects that diversify connections but remain wary of debt traps or being drawn into great-power rivalries.

- From forum to platform: Despite deep political differences, SCO members increasingly converge on economics and supply-chain resilience as areas of shared interest. Tianjin signaled a pivot from symbolic declarations toward potential institutional development.

- Implications for the West: Treating the SCO as irrelevant is no longer viable. The bloc is unlikely to become a military alliance, but it is emerging as a functional coordination mechanism. The challenge for Western powers is to compete with credible alternatives, engage selectively, and avoid forcing binary choices on smaller states.

- The “Tianjin Test”: The summit crystallized both the promise and the limits of the SCO. Its credibility now rests on whether it can move from rhetoric to delivery—by launching a bank, sustaining Sino-Indian diplomacy, and navigating Russia’s constrained role.

Introduction

From August 31 to September 1, 2025, Tianjin hosted the 25th Heads of State Council of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)—a meticulously choreographed gathering that doubled as a stress test of Eurasia’s power geometry. With China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and India’s Narendra Modi headlining, the summit showcased Beijing’s push to recast the SCO from a security forum into a developmental platform; highlighted a tentative thaw in Sino-Indian relations; and offered Moscow a stage to signal diplomatic openings on Ukraine. Leaders capped proceedings with a Tianjin Declaration, underscoring the SCO’s bid for greater political and economic weight. For policymakers, the meeting’s optics and outcomes together map the contours of a still-forming Eurasian order.

A Bloc in Transition

Founded in 2001 by China, Russia, and four Central Asian states, the SCO today counts ten full members after Belarus’s accession in 2024, with a wide circle of observers and dialogue partners. The bloc remains centered on security cooperation, but it increasingly serves as a political and economic convening mechanism across a vast Eurasian space. The Tianjin summit’s guest list—over twenty national leaders plus multilateral chiefs—underscored that broader ambition and gave China a marquee diplomatic moment.

For Beijing, hosting the 25th anniversary-adjacent summit on home soil was an opportunity to reinforce the SCO’s identity as an inclusive, multipolar framework—not an anti-Western alliance, per official rhetoric, but a vehicle to rebalance global governance. That narrative suffused the two days in Tianjin.

Xi’s Vision: Finance as Glue

Chinese President Xi Jinping set the summit’s direction with a speech that went well beyond the ritual calls for unity. At its core was a renewed push for an SCO development bank, an idea floated in the past but never institutionalized. This time, Xi paired the concept with tangible commitments: fresh aid packages, loan facilities, and promises of cooperation in infrastructure, energy, digital technology, and artificial intelligence. The subtext was unmistakable—if the SCO is to be more than a ceremonial forum, it must be able to deliver hard assets and financial muscle, not just declarations.

But behind the economic pledges lies a strategic recalibration. By proposing a dedicated SCO financial arm, Beijing is attempting to move the bloc into territory where it can shape regional flows of capital and trade rules. A bank under SCO branding would complement—but not duplicate—the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Unlike BRI, which is often bilateral and China-led, an SCO bank could be marketed as multilateral and rules-based, offering smaller members more ownership while still keeping Beijing at the center.

Equally significant is the push for local-currency settlement. By embedding such mechanisms in the SCO’s financial framework, China aims to gradually reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar for intra-bloc trade. For Beijing, this is not only about hedging against sanctions risk but also about future-proofing Eurasian commerce against global financial volatility. For smaller members, local-currency financing could reduce exposure to currency shocks and open new pathways for investment.

The timing is not accidental. With global supply chains under pressure from geopolitics, climate disruptions, and technological bifurcation, Xi’s pitch framed the SCO as a shield against fragmentation. A functioning development bank, paired with infrastructure corridors and shared digital standards, could allow member states to trade, finance, and build in ways less vulnerable to external shocks. In essence, Xi was proposing that finance and connectivity become the glue binding together a politically diverse bloc.

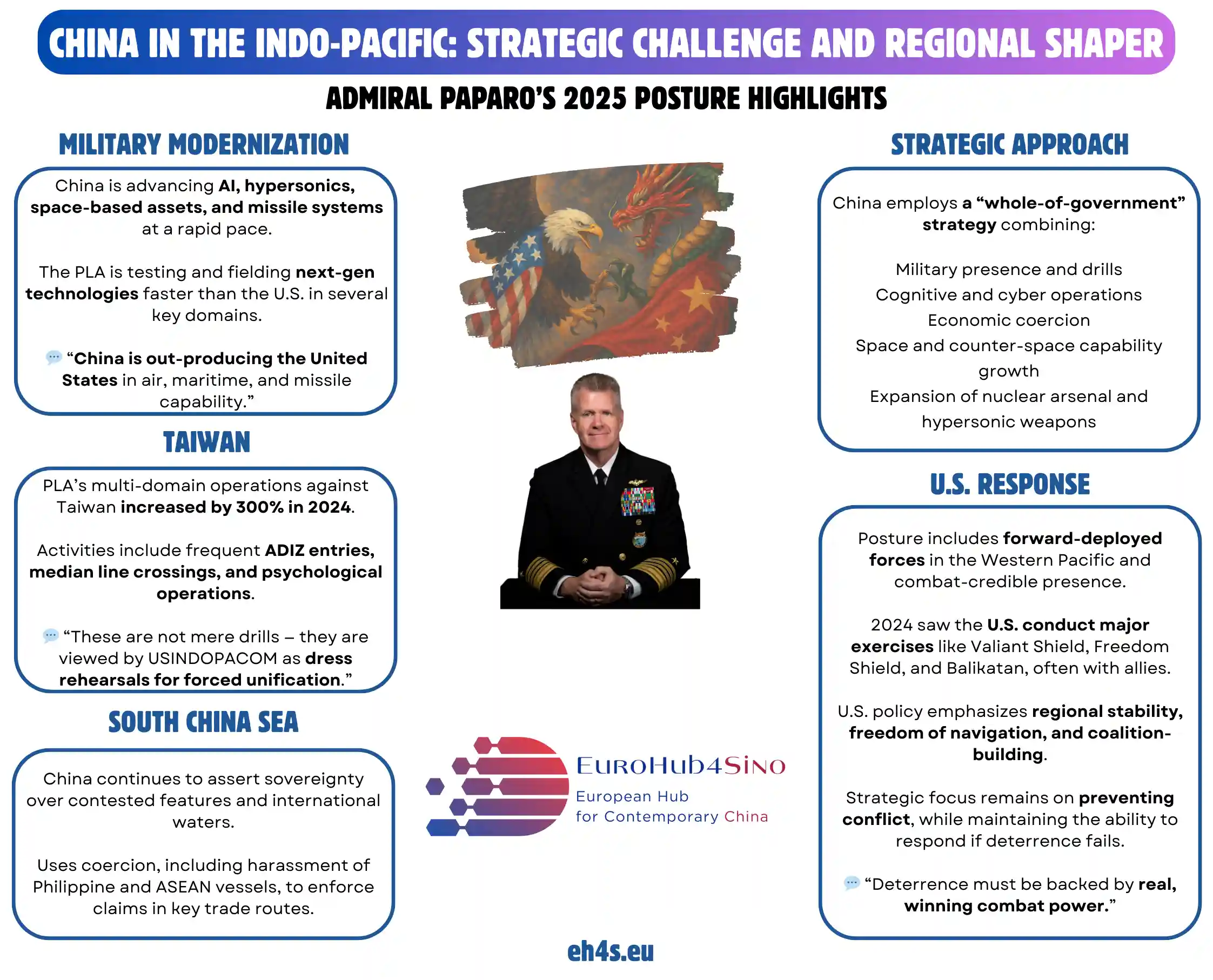

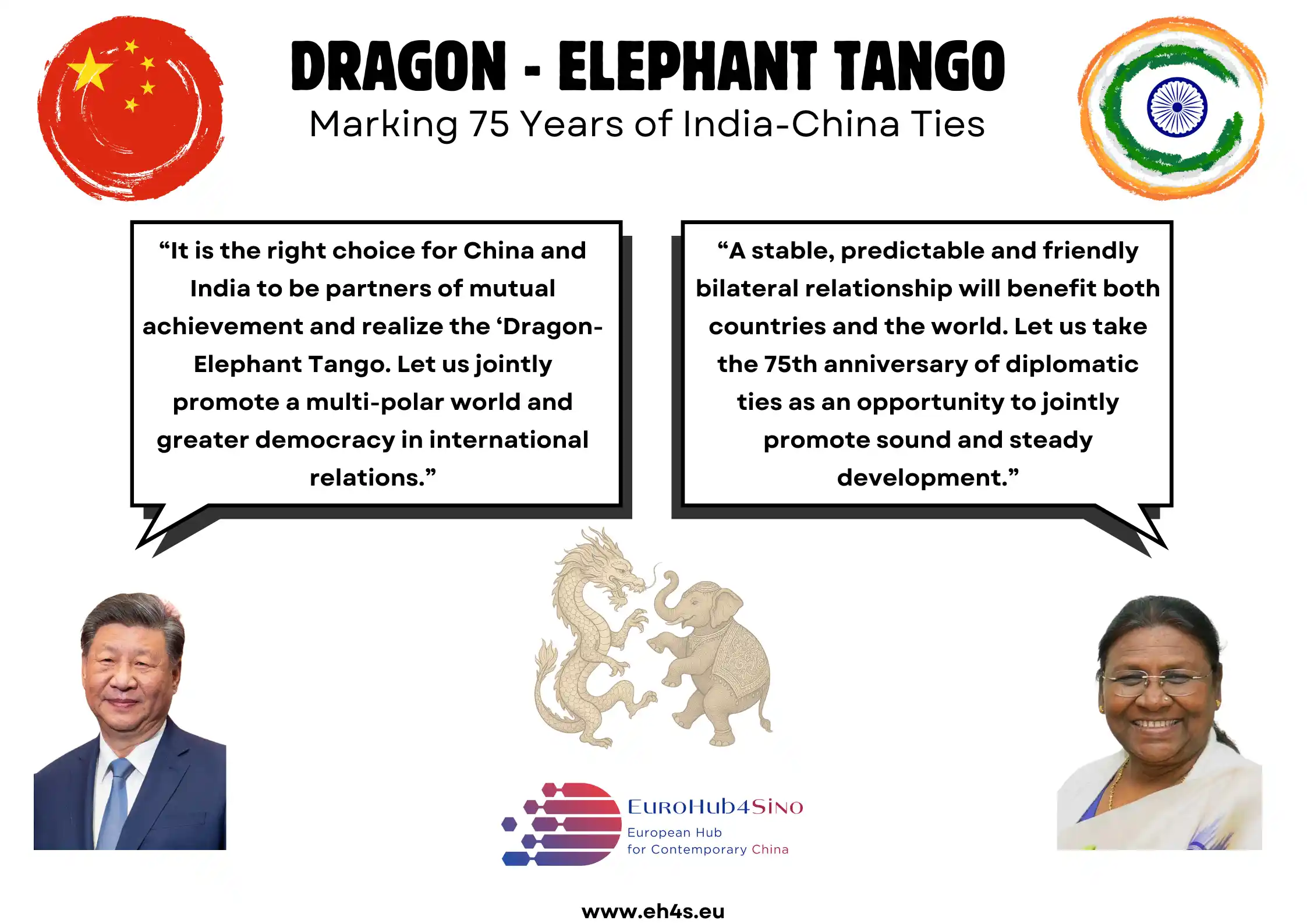

Modi and Xi: a cautious thaw

For many observers, the real story in Tianjin unfolded not in the summit hall but in the quieter corridors of bilateral diplomacy. The meeting between Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was their most substantive encounter since the deadly 2020 Galwan Valley clashes, which plunged relations into a prolonged freeze. The two leaders did not announce breakthroughs—no new border agreements, no grand gestures—but what they did signal was arguably just as important: a willingness to rebuild trust incrementally.

Both pledged to manage differences, particularly along the disputed Himalayan frontier, and to expand avenues of cooperation in trade, technology, and regional stability. This cautious language masked deeper strategic calculations. For New Delhi, easing the strain with Beijing provides badly needed breathing space. India is strengthening its partnerships with the United States, Japan, and Australia through the QUAD, but it also knows that perpetual confrontation with China consumes diplomatic bandwidth and risks unpredictable crises. A managed relationship, even if tense, gives India more leverage across multiple fronts.

For Beijing, the stakes are equally high. China is trying to reframe the SCO as an economic and financial platform; having India as an obstructive member would threaten that vision. By signaling a thaw, Xi sought to ensure that the bloc does not fracture along its most dangerous seam. It also allows Beijing to portray the SCO as a space where even rivals can find common ground, reinforcing its narrative of the organisation as a pragmatic, multipolar forum.

Yet the thaw remains fragile. Trust deficits linger, troop deployments along the Line of Actual Control remain high, and domestic political rhetoric in both countries still casts the other as a primary challenger. What Tianjin revealed was not reconciliation but a mutual recognition of necessity: neither side benefits from letting tensions spiral, and both see value in stabilizing the relationship while keeping their broader strategic bets open.

Putin’s Messaging: A Signal on Ukraine

If China’s Xi Jinping was intent on anchoring the SCO’s future in economics, Russia’s Vladimir Putin used Tianjin to craft a very different narrative—one that blurred diplomacy, symbolism, and strategic positioning. Fresh from the August summit in Alaska with U.S. officials, Putin arrived in Tianjin with a message designed to capture attention: that certain “understandings” had been reached with Washington, potentially paving the way toward a peace framework in Ukraine.

Whether those “understandings” amount to concrete steps or mere diplomatic smoke remains uncertain. But in Tianjin, that ambiguity was itself a tool. By floating the prospect of movement, Putin could signal flexibility to the West while simultaneously reassuring non-Western partners that Russia was not permanently locked in confrontation. It was a balancing act: project momentum without conceding weakness.

The SCO stage was perfectly suited to this message. In front of leaders from Asia, the Middle East, and Central Asia, Putin framed Russia as a responsible stakeholder committed to “genuine multilateralism.” This phrase—repeated often in Moscow’s rhetoric—functions as shorthand for a world order where U.S. dominance and the dollar’s primacy are diluted by regional institutions, alternative financial networks, and new alignments.

For Russia, still deeply sanctioned and diplomatically ostracized in Western forums, the SCO is one of the few spaces where it can appear not isolated but legitimately courted. The warm optics of Tianjin —handshakes, plenary sessions, and bilateral meetings—helped project the image of Russia as a central player in Eurasia, rather than a pariah.

Yet beneath the theatrics lies a reality Moscow cannot escape. Its war in Ukraine has constrained its economic bandwidth and narrowed its diplomatic options. The SCO gives Russia a platform, but not a blank check. Members like India and the Central Asian states are wary of being drawn too closely into Moscow’s orbit, especially when sanctions exposure could harm their own economies. The irony is that the more Putin leans on the SCO for legitimacy, the more he must accept a secondary role in an organisation where China now sets the economic agenda.

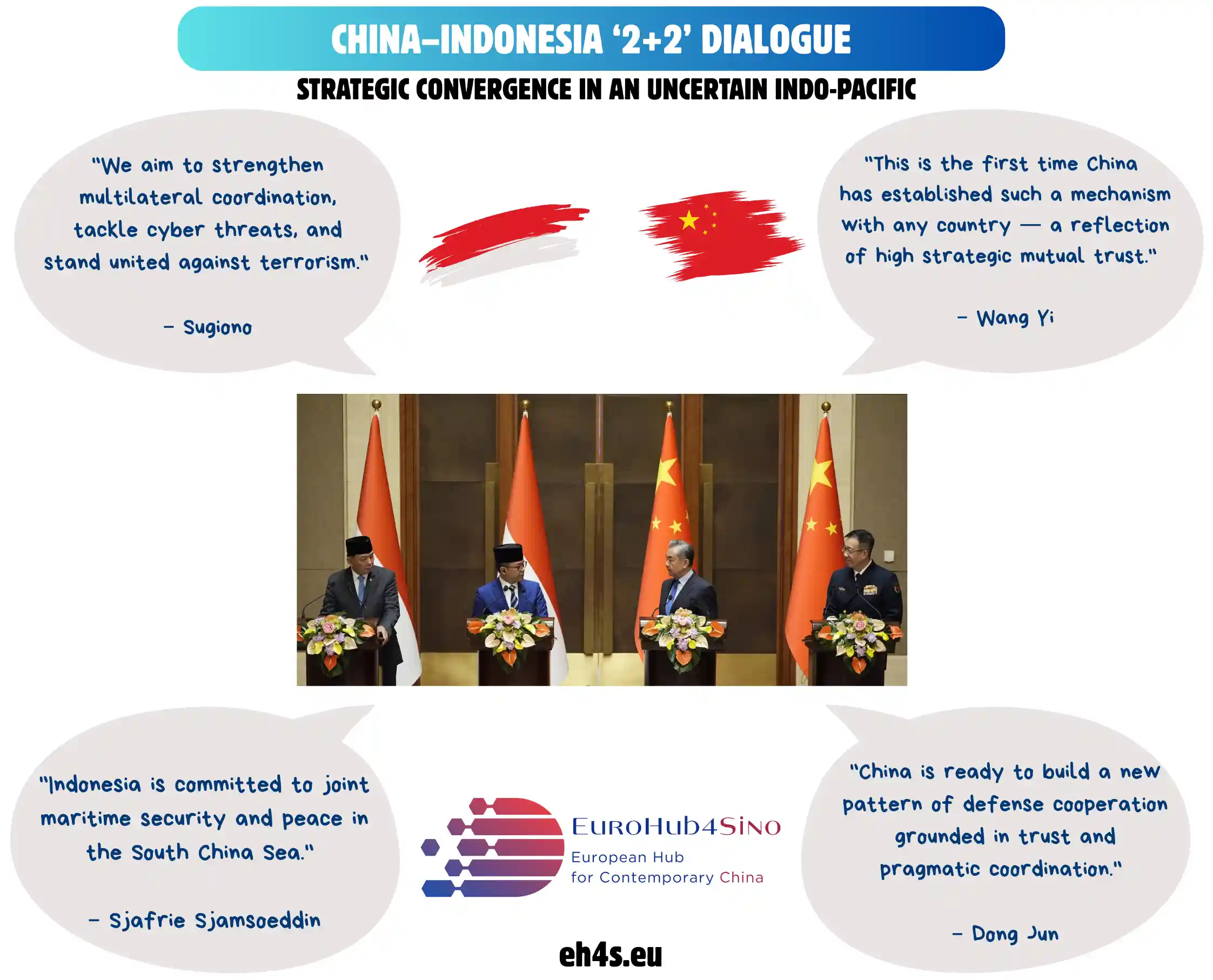

Central Asia’s Careful Balancing

For the Central Asian republics, the SCO has always been more than a diplomatic club; it is a tool for strategic navigation between powerful neighbors. At the Tianjin summit, this balancing act was on full display. The region’s leaders welcomed talk of infrastructure loans, new transport corridors, and expanded energy links. Such projects promise to knit Central Asia more tightly into global supply chains and reduce its traditional dependence on Soviet-era infrastructure.

Yet opportunity here is inseparable from caution. These states—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—know from experience that connectivity can be a double-edged sword. While new pipelines, rail lines, and digital grids may generate growth, they can also deepen dependence on a single patron. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has already poured billions into Central Asia, sparking both gratitude and quiet concern over debt sustainability and sovereignty risks. Russia, meanwhile, remains a critical market and security guarantor, but its war in Ukraine has exposed the fragility of over-reliance on Moscow.

The SCO therefore functions as both an opportunity and a hedge. By engaging within this framework, Central Asian states can extract financing and political attention from China and Russia, while simultaneously broadening ties with India, Iran, and now Belarus. It is a delicate equilibrium: to take enough from each great power to prosper, but never so much that they lose room to maneuver.

Tianjin highlighted the principles shaping their calculus. SCO-backed projects that diversify corridors—for example, linking Central Asia to South Asia via Afghanistan, or strengthening east–west routes through the Caspian—are welcome, especially when backed by transparent procurement and shared governance. But initiatives that lock them into opaque debt deals, or that turn their territory into a geopolitical battleground, will be quietly resisted.

Why Tianjin matters

The Tianjin summit was never about producing dramatic breakthroughs; it was about signaling direction. What emerged was a picture of a bloc gradually redefining its purpose. China used the moment to push the SCO toward institutionalizing its economic and financial role, offering the idea of a development bank and real lending commitments. India, while still cautious of Beijing, showed itself willing to practice a form of managed engagement, balancing rivalry with cooperation in order to safeguard its own room for maneuver. And Russia, still constrained by the war in Ukraine, sought to project itself as indispensable, leveraging the SCO stage to claim relevance and to promote a multipolar vision of global order.

Beneath these moves lies the SCO’s most notable evolution: despite deep internal divisions, the group is beginning to find common ground in economics and supply-chain resilience. Security cooperation remains patchy and politically sensitive, but finance, infrastructure, and trade are areas where members see shared interests and tangible payoffs. That makes Tianjin less of a turning point and more of a pivot point—a moment when the SCO began to transform from a loose political forum into a potential institutional hub of Eurasia’s connectivity.

For the West, the implications are clear. Dismissing the SCO as an irrelevant talk shop is no longer viable. While the bloc is not about to become a military alliance or an economic powerhouse overnight, it is slowly acquiring the features of a practical coordination mechanism. That matters because institutions, once built, create habits of cooperation, lock in financial flows, and shift political expectations. If Tianjin’s proposals take root, they could redraw parts of Eurasia’s economic map in ways that bypass Western-led systems.

The challenge, then, is not to overreact but to engage smartly. For Washington, Brussels, and their partners, the task will be threefold: to compete with credible alternatives in infrastructure and finance, to engage selectively on areas of overlap such as counterterrorism or climate security, and to avoid binary choices that force smaller states into rigid alignments. Tianjin’s lesson is that the SCO is no longer a sideshow—it is an experiment in multipolarity, and its trajectory will help shape the future of Eurasian order.

Conclusion

The SCO summit in Tianjin was both performance and policy—a carefully staged theatre of multipolarity and an experiment in institution-building. Its lasting significance will not be measured by the declarations issued over two days, but by what follows. Will the proposed development bank be capitalized and governed in a way that gives the SCO genuine financial heft? Can the tentative Sino-Indian thaw survive the volatility of border politics and domestic pressures? And will Russia’s talk of “understandings” on Ukraine translate into real diplomatic movement, or fade into familiar ambiguity?

If these threads align, Tianjin could be remembered as the moment the SCO crossed a threshold, moving from a rhetorical forum into a structure capable of shaping Eurasia’s economic and political order. If they do not, the summit risks being catalogued alongside others that produced striking images but little substance.

Either way, the “Tianjin Test” has set a benchmark. It showed that the SCO has the potential to evolve into something greater than the sum of its parts, but also that its credibility will hinge on delivery, not ceremony. For policymakers and analysts alike, that makes Tianjin less an endpoint than a starting gun—a moment that crystallized both the promise and the limits of Eurasia’s most ambitious regional experiment.

Related Infographics