Abstract

Humans have witnessed many wars throughout the history. The weapons, equipment, tactics, doctrines and strategies used in these wars have been in a constant evolution. This evolution of warfare has depended on technological level, changes in the societies, global security environment, governance of the states, innovation and creative thinking. Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD) is one of the most popular military strategies in recent years. US has expressed concern for the Chinese military initiatives in the Pacific region. Russia adopts the same approach against American Style warfare and has already created A2AD bubble zones in the NATO’s eastern and southern flanks, which would have severe implications that NATO is to take into considerations.

1. Introduction:

After a short glance at the evolution of warfare in chronological order in the first part, the definition, background and the main characteristics of A2AD is presented in the second part, third part summarises the Russian military activities and A2AD strategy, and finally the last part exhibits the implications of Russian A2AD strategy for NATO.

2. Evolution of Warfare:

There are many studies to categorise evolution of warfare. Some of them categorise it in terms of ages, some of them waves and some of them generations. In this study, evolution of warfare is summarized in chronological order.

Warfare has been in an evolution fueled by; changes in technology, global security environment, competition between offence and defence, governance of states and so on so forth. Until the introduction of gunpowder to the battlefield, wars were generally fought between city-states and swords, shields, spears, bows, arrows etc. were the most prominent weapons used by soldiers. Ships were used mainly for the transportation. While the phalanx system was used by some nations, Roman legions were created and effective against it. Cavalry was used to overcome the deadlocks. In this era, battles lasted for very short time periods.

With the invention of the gunpowder, the face of the war changed dramatically. Most of the basic elements of the warfare such as tactics and weapons became obsolete. Cannons and muskets became indispensable. Castles were not as impregnable anymore and the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Empire was an apparent evidence of the revolutionary effect. Efforts for defense triggered new types of precautions such as construction of new types of the castles, fortification of walls, deployment of archers and cannons on the bastions etc. The offense side concurrently developed engineering and mining. With the 14th century, Chinese and Spanish started to deploy cannons to ships and seas became another important domain in the battlefield. In the 15th and 16th century, the battles lengthened. The sieges were lasting for a long time; for example, Spanish, French, Ottoman, Austrian and Russian armies were in the war in 2 of the 3 year-periods. The proliferation of the rifles with the extended ranges and the new tactics and orders of battle became prevalent in the 18th century. Clausewitz defined the war with physics rules such as momentum, mass, acceleration etc. with his book ‘On War’. The generals indoctrinated with his ideas during 20th century used these principles in the World War I. The unprecedented firepower forced the infantry to dig into the trenches, and World War I became known as ‘Trench Wars’.

World War II witnessed to many revolutionary events with lessons learnt from the first. Tanks and warplanes became a game changer in the battlefield. ‘Blitzkrieg’ doctrine was used by Germans to overcome the trenches and advance deep into enemy rear. The parachute troops were very effective to surround adversary and radio was very useful to develop the command and control and allowed small troops to conduct operations in extended distances. Atomic Bomb was, of course, the most important determinant factor to end the war. It caused great losses for Japan and made them surrender. [1] With the introduction of the Atomic Bomb, a new doctrine as ‘Nuclear Doctrine’ has evolved.

After World War II, a two polar World emerged, and colonies declared independence wars employing doctrines like Mao’s ‘Protracted War’ and guerilla strategies in their struggles. For the first time, an international organisation- UN became a side of the war in the Korean War. On the other hand, with use of atomic bomb, a nuclear race has begun, and several nations have acquired this capability. Those nations adopted ‘’Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)’’ doctrine for deterrence[2]. Arab-Israel wars revealed the importance of strategic surprise, air defence systems, use of mechanised and armoured troops, improved logistics etc. While the 1973 Yom Kippur War testified the effects of technological advances in weapons technology, USSR’s Afghanistan War revealed the fact that Soviets had closed the quality gap with the US regarding military technologies. The Air-Land Battle concept was developed by the US to overcome operational problems faced by NATO on the European Central Front against USSR in the cold war.

Air-land Battle concept which was based on the integration of abilities of two services enabled armies to fight deep with the development of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) systems and long-range fighting and shooting capabilities. The extended battlefield regarding time and geography enabled attacking to the second-echelon forces and preventing the reinforcement of Forward Edge of the Battle Area (FEBA) troops and gain initiative[3]. The doctrine paved the way for developments of new tactics and weapons systems, and a similar NATO operational concept known as Follow-on Forces Attack (FOFA) as well. These developments, in turn, allowed changes in the way of deterrence and planning fighting[4]. The world witnessed the first Gulf War, in which US-led coalition used this doctrine. In the beginning, air campaign was executed to silence Iraq’s air defence systems and then land offenses launched with the close support of air forces. New technologies and tactics, which were developed during the cold war, were employed for the first time.

With the end of the cold war, NATO assumed an international role for the crisis areas around the world. It carried out campaigns in Bosnia in 1995 and Kosovo in 1999. UN sent troops to Somalia in 1992. These operations revealed that tolerance for losses was a key factor to new way of fighting.

After 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States, US and her allies -and later NATO- launched a war against terrorism in Afghanistan in 2001. In 2003, US initiated second Gulf War in Iraq claiming that Iraq had Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). The war broke out between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006. We have been witnessing ever-mounting Russian aggression since 2008. Russia carried out a campaign against Georgia in 2008. It also initiated so-called hybrid warfare[5] against Ukraine and destabilised it. In 2014, it occupied and annexed Crimea with conflict still ongoing in the east of Ukraine supported by Russia. Finally, Russia launched a campaign in Syria alleging that Syrian government called her to help Syrian government to fight against terrorism.

When we analyse the recent wars, we recognise many important and common aspects in most of these wars:

- The actors of wars have changed and non-state actors (e.g. terrorist organizations, international organizations, NGOs, foreign fighters, proxy rebel factions etc.) have become key players in war.

- Strategic communication (Stratcom) namely, winning hearts and minds of people to get their support, has become indispensable to be successful.

- Cyber warfare has evolved as a new domain of battlefield and it has been applied concurrently or separately against adversaries.

- Beginning and end of wars has become increasingly vague.

- Hybrid warfare has emerged as a new strategy and way of waging war.

- Proxy war has been applied as an indirect way of carrying out campaigns by using proxies rather than routine forces.

- The battlefield has been used as a laboratory and most recent technologies and war fighting concepts have been tested.

3. Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD):

Adversaries always tried to prevent their opponents from approaching and attacking their territories or deter them to do such acts to protect their people and interests throughout the history. They have built castles, trenches, walls (e.g. Great Wall of China), defence lines (e.g. Maginot Line) and now A2AD capabilities to undermine the freedom of movement and operational access of foes. After the cold war, US became the most powerful nation with immense military power. US carried out operations in Iraq twice (In 1991 and 2003) and exhibited her way of war-fighting. This kind of superiority and war-fighting naturally triggered some initiatives to develop counter capabilities and strategies. Having witnessed the US’s way of fighting and experienced events like the 1995-1996 Taiwan Crisis and the 2001 Hainan Island Crisis, China started to develop an A2AD strategy. However, the most dangerous and aggressive one for security environment in NATO’s eastern and southern flanks is, of course, Russia. Russia has begun to develop A2AD capabilities to create a buffer zone to compensate her losses after the Cold War. So; what is A2AD? What does this strategy envision? And what those A2AD capabilities are?

US’s ‘Joint Operational Access Concept’ defines these two terms Anti-Access and Area Denial as the following; ‘anti-access refers to those actions and capabilities, usually long-range, designed to prevent an opposing force from entering an operational area. Anti-access actions tend to target forces approaching by air and sea predominantly, but also can target the cyber, space, and other forces that support them. Area-denial refers to those actions and capabilities, usually of shorter range, designed not to keep an opposing force out, but to limit its freedom of action within the operational area. Area-denial capabilities target forces in all domains, including land forces. The distinction between anti-access and area-denial is relative rather than strict, and many capabilities can be employed for both purposes. For example, the same submarine that performs an area-denial mission in coastal waters can be an anti-access capability when employed on distant patrol’.[6] As seen in abovementioned definitions, while anti-access capabilities aim to prevent or deter any adversary to enter an operational area, area denial capabilities are to hamper or degrade freedom of manoeuvre within an operational area. Generally anti-access capabilities have longer ranges than area denial capabilities. Since anti-access capabilities can be used for both anti-access and area denial purposes, they encompass area denial capabilities as well. This strategy in one hand aims to dissuade or prevent any adversary to project power and perform actions near the borders, on the other hand, -thanks to A2AD capabilities’ offensive nature- it has a high potential to be used for offensive purposes. A2AD capabilities/means include many domains varying from political to military. As comprehensive approach suggested; it requires taking all kinds of capabilities into account. Some examples of existing and emerging A2AD capabilities may be listed as[7];

- Multi-layered integrated air defense systems (IADS), consisting of modern fighter/attack aircraft, and fixed and mobile surface-to-air missiles, coastal defense systems,

- Cruise and ballistic missiles that can be launched from multiple air, naval, and land-based platforms against land-based and maritime targets,

- Long range artillery and multi launch rocket systems (MLRS),

- Diesel and nuclear submarines armed with supersonic sea-skimming anti-ship cruise missiles and advanced torpedoes;

- Ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) force,

- Advanced sea mines

- Kinetic and non-kinetic anti-satellite weapons and supporting space launch and space surveillance infrastructure,

- Sophisticated cyber warfare capabilities,

- Electronic warfare capabilities,

- Various range ISR systems,

- Comprehensive reconnaissance-strike battle networks covering the air, surface and undersea domains; and

- Hardened and buried closed fiber-optic command and control (C2) networks tying together various systems of the battle network,

- Special Forces etc.

With these capabilities; any operation can be carried out by any state’s air forces and integrated air defences to have or keep air superiority or parity over its sovereign areas or its forces. Operations with Special Forces, artillery and multi-launch rocket systems (MLRS) and missiles against forward-based forces and deploying forces can be executed in any entry points to the area of operations. Additional to land-based capabilities; maritime capabilities such as anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles and submarines armed with torpedoes or anti-ship cruise missiles, sophisticated mines, coastal submarines, and small attack craft could be employed as well.[8]

4. Russian Military Activities and A2AD Strategy:

Since the end of the Cold War, Russia has been adapting itself to the New World Order while facing difficulties. It has not been easy for a superpower of Cold War era to get accustomed to second rate status. Dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and independence of old Soviet nations caused great problems for the new Russian Federation (RF). Loosing these countries and then the enlargement of NATO and European Union towards the east has made the security environment much more concerning for RF and contributed to a Russian perception of an increasing threat to its interests.

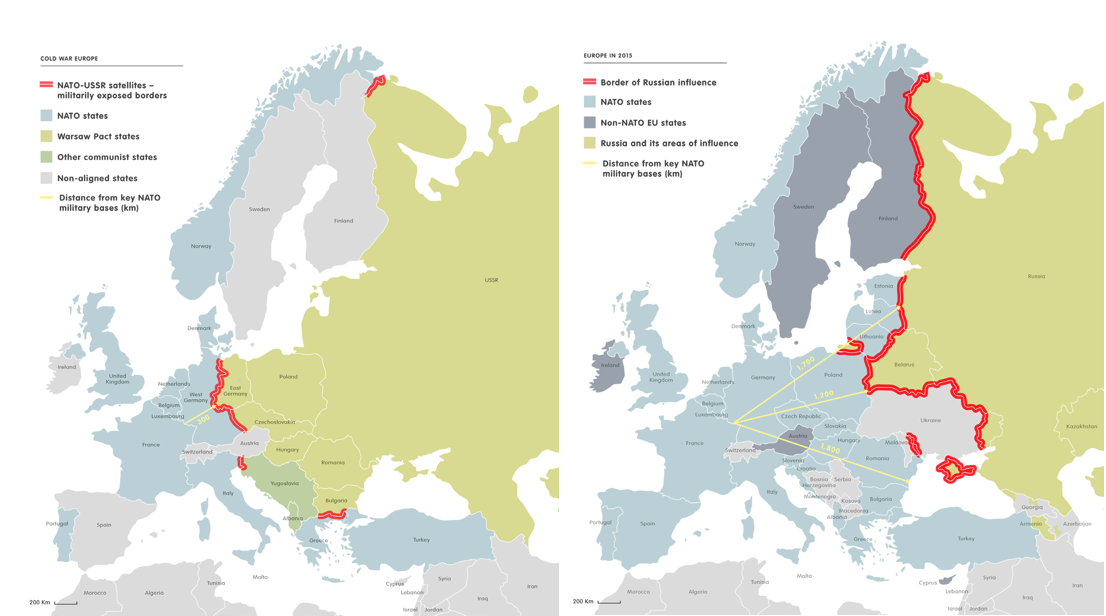

The European Council on Foreign Relations October 2015 policy brief[9] exhibits Russia’s ‘then and now’ view of NATO’s enlargement. Figure 1 illustrates comparatively the border between NATO/EU and the USSR during the Cold War era and afterwards. During the Cold War, the borders between NATO/EU and Eastern Bloc countries were incomparably shorter than those, which exist today between NATO/EU and Russia. Since geography is a very critical factor for defence policy and thinking, so this fact goes for Russia as well. During the Cold War, USSR had a ‘strategic buffer zone’ between NATO and the homeland (Russia) through Warsaw Pact states. This buffer zone provided Russia to maintain a defence in depth and to have the opportunity to keep freedom of movement (FoM) within its territory to respond to attacks. The current situation, shown in the right side of Figure 1, exhibits the loss of so-called ‘Zone of Privileged Interest’, the strategic buffer zone, thereby losing the ability and opportunity abovementioned.

Figure 1: Map of the comparative border between NATO/EU and the USSR during the Cold War era and afterwards[10].

When Russia felt that it had been losing its influence over its alleged privileged zone, it started to compensate these losses by a new strategy with the help of its economic growth, political stability and momentum of the Russian leadership under Putin. After Cold War; Russia has published its top strategic documents such as ‘National Security Strategy (1997, 2000, 2009 and 2015), Foreign Policy Concept (1993, 2000, 2008 and 2013) and Military Doctrine (1993, 2000, 2010 and 2014)’ four times to renew its approach and perspective and adapt itself to the dynamic and complex security environment.

The National Security Strategy, the overarching document outlining Russian vision in security domain, reinforces the idea that Russia aims a ‘multipolar’ or ‘polycentric world’ and it wants to secure a place in the new global security environment as a leading world power. Russia’s handling of the Syria crisis exhibits its willingness to use military power to achieve its desired status and to pursue its strategic interests.

Russia defines NATO’s expansion and transformation as a threat for the first time; ‘The build-up of the military potential of NATO and vesting it with global functions implemented in violation of norms of international law, boosting military activity of the bloc’s countries, further expansion of NATO, the approach of its military infrastructure to Russian borders create a threat to the national security’.[11]

Russia finds NATO’s increased military activity, the approach of its military infrastructure to Russia’s borders, the creation of a NATO missile defence system, and efforts to develop a global role for the Alliance as unacceptable and against to its national interests. It considers developing cooperation with NATO would only be based on ‘equal relations’, and taking into account Russia’s ‘legal interests’, notably ‘when conducting military-political planning’ and NATO’s readiness to ‘respect the provisions of international law’.

Russia emphasises the importance of military domain regarding strategic deterrence and the prevention of military conflicts by maintenance of a sufficient level of nuclear potential and military forces at their assigned readiness for combat employment.

After the war in Georgia; Russia realized its deficiencies and launched a military reform in late 2008. The reform was planned in three phases; first, enhancement of professionalism by increasing educational level and decreasing the number of conscripts; second, improvement of combat-readiness by reorganising command structure and increasing exercises; and third, modernisation of arms and equipment[12].

– The first part of the reform is completed resulting in a more streamlined command-and-control chain and a pyramid personnel structure with few higher educated senior level officers at the top.

– The second phase has been successful in increasing troop readiness and improving organisation and logistics. Russia reorganised the entire structure of its armed forces by dissolving its divisions and introducing new brigades with high-level readiness. The number of military districts was reduced, and they were converted into joint forces commands, thereby allowing them to all land, air, and naval forces in their zone. The number of manoeuvres and exercises/snap exercises were increased so as to enhance the combat-readiness. The goal is to deploy all airborne units and to make all Russian new brigades ready to deploy within 24 hours of alert.

– The aim for initial stages of the third phase was not to modernise weapons and equipment, but rather to ensure effective use of existing weapons and equipment. The introduction of new weapons and equipment has just begun only recently. However, the straining of NATO/EU-Russian relations after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military activities in eastern part of Ukraine, and severe economic conditions due to the collapsing oil prices, have caused several delays for Russian modernisation programmes. It looks like that this phase will continue throughout coming decades due to these postponements[13].

Despite abovementioned postponements, Russia has improved the quality, quantity and capability of its armed forces to close the gap with NATO. It has developed advanced capabilities in terms of space, cyberspace, and across the electromagnetic spectrum. Russia deployed these new capabilities in a fashion that restricts, or imposes consequence, friction and cost on NATO FoM and operations. Advanced A2AD capabilities exhibit many challenges to the Alliance while providing Russia increasingly assured FoM and operation.

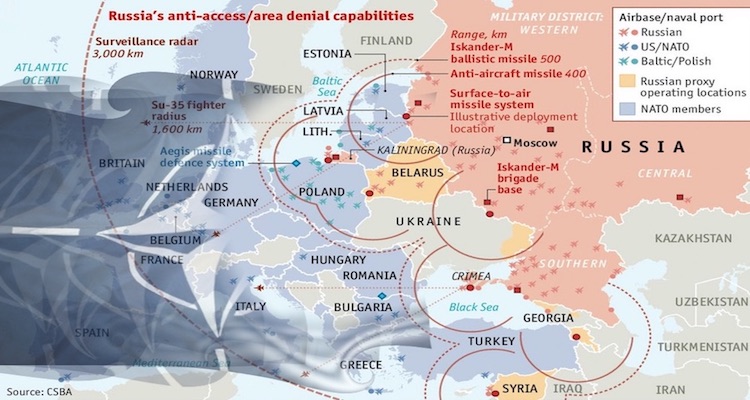

Russia’s recently deployed advanced A2AD capabilities such as; long range precision air defence systems, fighters and bombers, littoral anti-ship capabilities and ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare), mid-range mobile missile systems, new classes of quieter submarines equipped with long range land attack missiles, counter-space, cyberspace, & EW weapons; and WMD assets in Kaliningrad in Black Sea and partly in Syria have changed the military environment. With additional deployments -thanks to modernization expected by 2020s- battlefield will be more complicated than ever. These A2AD capabilities allow Russia to have a new strategic buffer zone between NATO and Russia, but this time within Alliance` own territory. They provide the ability to target a large part of the Europe to influence, deter and deny NATO’s potential operations in the High North, Baltic, Black Sea and East Mediterranean regions. The figure[14] below depicts only a part of the Russian A2AD capabilities.

Figure 2: A partial depiction of Russian A2AD capabilities along the NATO’s eastern and southern borders.

5. The Implications of Russian A2AD Strategy for NATO and Potential Measures

Russia uses A2AD strategy as part of a comprehensive approach for deterrence, and it would employ it to neutralise NATO’s military advantage during time of peace, crisis and war:

a. In the peacetime; Russia’s A2AD capabilities, given their coverage of NATO’s territory, becomes a potential threat and limit Alliance’s freedom of movement even within own territory.

b. During a crisis; Russia could attempt to deter Alliance military activities through show off its A2AD capability, with concurrent snap exercises and military preparations. Moreover, it would probably use its cyber/electronic warfare capabilities to reduce NATO’s situational awareness and strategic anticipation, through blinding Alliance’s ISR, radars and communications. More importantly, prolonged A2AD bubbles created by Russia outside of its territory -such as Syria-, would enable Russia to have a constant justification to project its forces and blur the distinction between force movements for exercises or a real preparation to escalate tension leading to hot conflict. This also enables Russia to seize the initiative to determine the course of an emerging crisis. Crisis such as Syria provides Russia with the opportunity to test its newly developed long-range weapon systems and associated technics, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) in order to advance its warfighting capabilities versus NATO.

c. In a conflict, Russia would try to isolate the theatre of operations from NATO’s forces while dislocating threatened nation’s defence forces and those already forward deployed. Given the NATO’s system of responsive reinforcement, it would be clear that the Russian A2AD strategy is specifically developed to prevent establishment of initial NATO forces on the theatre and to threaten follow-on forces. Even if NATO forces could be deployed to the theatre of operations, they will face these advanced systems within area of operations. With its advanced A2AD capabilities; Russia could attempt to[15];

- Threaten all NATO bases/troops/assets close to the Russia,

- Deny NATO force deployment to the area of operations,

- Disrupt NATO Navy surface and submarine operations and threaten them out to an extent where they may not operate effectively to target Russian forces by deployment of sophisticated sensors and weapons in littoral waters and narrows,

- Challenge NATO air operations with its air force and integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) systems,

- Impede NATO to use space effectively for ISR, command and control (C2), communications and for the purpose of targeting,

- Infiltrate to the NATO members close to Russia with its special forces or paramilitary units to foment hostilities against ruling authorities and other subversive purposes,

- Carry out electronic and cyberattacks against NATO battle networks to impair effective logistics, C2, fires, ISR, combat service support (CSS) and etc.

Russian A2AD strategy would cause dramatic changes in Freedom of Action (FoA). As abovementioned; in the event of conflict, Russia would attempt to restrict NATO’s FoM to deploy its initial, enhanced response and following forces to the theatre of operations and have a relative advantage to shape the battlefield. Possible effects of A2AD on FoM are;

– Situational awareness and strategic anticipation is sine qua non and should be enhanced by advanced joint ISR systems to a rapid political and military decision making.

– In order to negate the A2AD systems and to provide required FoM for NATO forces to deploy, there would be a need for entry operations against A2AD systems at the outset.

– The level of threat emanating from A2AD challenge would affect the type of deployment. While Russia would attempt to prevent any NATO deployment, NATO’s main effort would be to concentrate its forces to the battlefield. In this regard; developing alternative deployment methods and protection of the Lines of Communications (LoCs) would be very critical.

– In order to reduce the need for responsive reinforcement and have more force and capability close to Russia, an appropriate balance of forward presence and responsive reinforcement should be considered. While forward presence is an essential issue, the assured reinforcement would be crucial as well.

– A more geographically comprehensive approach for military plans would be required to overcome complex and sophisticated A2AD challenges. Moreover, these plans should be exercised to develop required level cooperation and collaboration within the allies and forces (Land, maritime, air and space, special forces). Especially, deployment and manoeuvre of forces in an A2AD environment should be the top two items that must be included in NATO exercises. These exercises would be very crucial to detect shortfalls and provide valuable feedback to create high-level competencies.

– NATO and member nations should develop new capabilities to demonstrate its ability and decisiveness to deter, deny, degrade and defeat A2AD threat whenever required. After the Cold War, NATO Nations cut the defence expenditures and gave priorities to the conventional capabilities, which may prove ineffective against such an advanced threat. NATO and member nations should take A2AD challenges into account thoroughly and reformulate their defence budgets prioritising the acquisition of weapon systems to confront dangerously evolving Russian A2AD zones in NATO`s area of interest.

– Current assurance measures may need to be modified accordingly.

– Overall effects of A2AD challenges on the battlefield functions should be examined in consideration with operational functions. Although these functions (manoeuvre, fire support, air defence, survivability, intelligence, combat service support (CSS), engineering and command, control, communication, computer and cyberwar (C5)) are mostly for army land operations, they are also very important for the other domains.

Indeed, means such as A2AD will enable further actions for Russia. According to Gerasimov ‘Each war does present itself as a unique case, demanding the comprehension of its particular logic, its uniqueness. It is why the character of a war that Russia or its allies might be drawn into is very hard to predict. Nonetheless, we must’.

In regard to NATO, under the negligible risk of response, i.e. staying under the threshold of Article 5, Russia achieves its objectives in Near Abroad, zone of privileged interests, Middle East and wherever they deem necessary. From NATO side, Corrosion in Cohesion of Alliance, confusion in seeking countermeasures were the results of the recent new generation warfare activities which may potentially undermine NATO’s collective security without a single shot[16].

What has NATO done so far to counter this unique challenge? General Philip M. Breedlove, then-SACEUR, suggested that NATO had to step back and ‘take a look at our capability in a military sense to address an A2AD challenge […] This is about investment. This is about training.’ Indeed, A2AD crosses the span of a solely military response and questions the ability of both political masters and military to effectively cooperate in order to overturn this challenge.

NATO’s philosophy to counter this threat swiftly unearthed but slowly evolved. To summarise; NATO must reinforce and protect those allies that are most vulnerable to A2AD capabilities. This is particularly valid for member states along the Alliance’s eastern flank, which may likewise require NATO’s lasting access to their region. This ‘enhanced forward presence’ should fill in as a tripwire, making any regional seizure a cause of potential escalation. Without question, the authorization of NATO’s eastern flank in its present state and nature, can’t constitute an adequate military power to contradict Russia’s military in an enduring and heightening conflict. But, what it can achieve is solidify NATO’s commitment to Article 5 and therefore deter Russia from any undertakings or escalating the conflict.

In that respect, the first case that rings the bell is the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis. In response to the Ukraine crisis, NATO invoked the Readiness Action Plan (RAP) which enhanced the NATO Response Force (NRF) Concept with the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) and secured the audit of Graduate Response Plans (GRPs) hoping to assure Allied Nations. With the execution of these plans, enemy A2AD naturally focus on the forces deploying into the theatre. Hence, NATO should be able to counter A2AD, creating a preferable air, ground, or maritime situation that permits beginning the Inside-Out Approach. If this cannot be provided outside of an A2AD zone, the necessary capabilities need to be already in place (pre-deployed) to create favourable circumstances[17].

NATO´s active response to the Russian A2AD challenge poses highly relevant political implications – not solely, on the future NATO-Russia relations, but also on the internal political situation in several NATO countries. Clearly, a sudden increment in countermeasures may cause a conflict risk – probably decrease the public support. NATO’s capacity improvement, not only in the Baltics, but also outside the area itself, should in this manner be suitably coordinated and addressed and communicated broadly to the public.[18]

So far NATO has been developing plans and developing its Technic, Tactic and Procedures according to the new reality. Exercises with appropriate training objectives are being implemented. In order to address the problem appropriately, this phenomenon is being discussed academically as well.

What could be the possible consequences and mitigations? These elements represent a specific test for military and political initiative taking part in unconventional warfare. Effective unconventional warfare commands a long-term approach, starting at Phase Zero before conflict breaks out. Phase Zero commitments are successful because they look to utilise non-military instruments to shape the operational environment, keeping the conflict from happening. However, they deliver few rewards that are clear to a sceptical public; tools of soft power, for instance, diplomacy, economic aid, and propaganda require patience perseverance and don’t create explicit, prompt pointers of triumph.[19]

From the strategic perspective; A2AD deserves to be studied not only through a military lens but also in the broader context. A2AD encompasses a significant part of the military strategy of Russia and using the term ‘A2AD as a stand-alone acronym’ would simply undermine the philosophy behind [20]. Therefore, A2AD phenomenon must be considered in the context of new generation warfare of Russia. It is a fair assessment to say that there are many tasks or things to be addressed well before tackling before A2AD and Russia’s advantage is more in Phase Zero activities. Although a Military Cooperation like NATO may have more resources than the opponent, they may not be enough to address the Russian new generation warfare. As Aleksandr Svechin wrote, ‘It is extraordinarily hard to predict the conditions of war. For each war it is necessary to work out a particular line for its strategic conduct. Each war is a unique case, demanding the establishment of a particular logic and not the application of some template.’ Therefore, NATO needs to adapt itself not only at operational and tactical aspects but also towards new generation warfare concept of Russia.

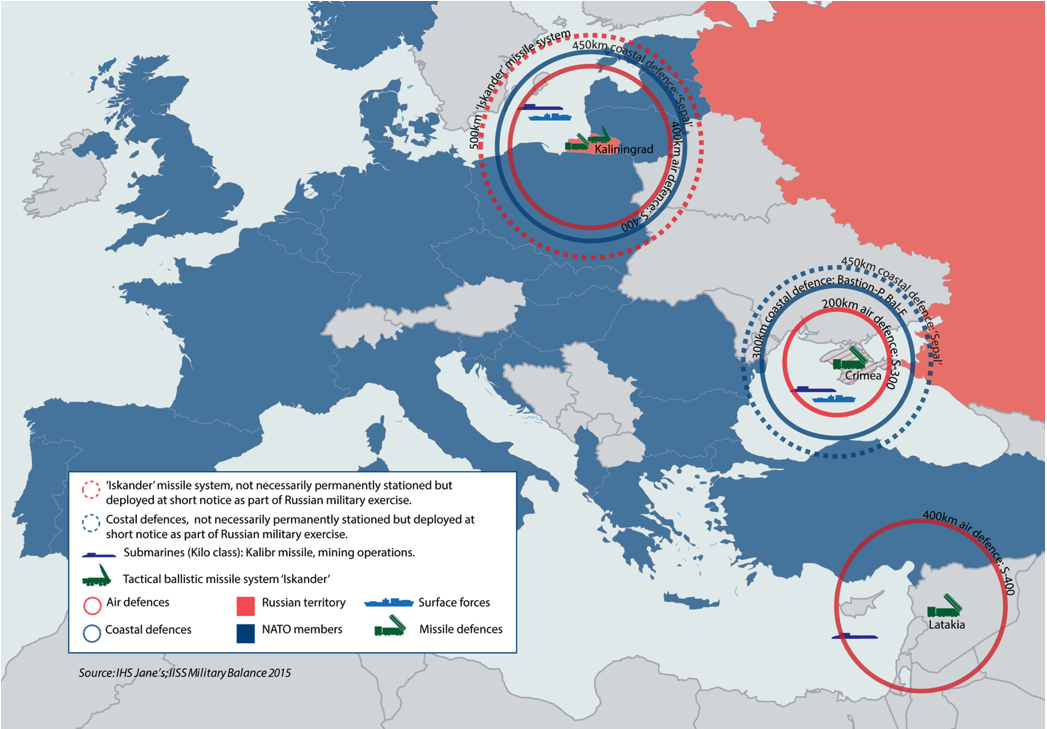

From the operational perspective; Russia operates advanced air defence not only within its territory but from sites in Syria and occupied Crimea, as well as cooperatively through the Joint Air Defense Network in Belarus and Armenia. Russia can implement these systems to hamper the ability of the US to defend its NATO allies by disrupting the ability of US air forces to access conflict zones during a crisis.[21]

Significant to NATO’s ability to come to the aid of an alliance member, is an arrangement of aerial and seaports of debarkation and embarkations (APODs/SPODs), vital to the rapid deployment of troops and equipment. Disabling these nodes would complicate NATO’s ability to effectively respond to the crisis, and as such, they would carry priority for air and missile defense coverage[22].

While A2AD challenges in the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean do not raise the same level of concerns (primarily due to the availability of various allied reinforcement and supply ´routes´) as the Kaliningrad-Baltic environment, their presence could pose a significant difficulty to the modality of continuous NATO missions at a later date[23].

From the tactical perspective; RF, considering the military superiority of NATO, has been developing asymmetric means of A2AD. The most essential of these comprise of S-300/S-400 and Bastion systems. The deployment of such measures in various regions (the Baltic Sea region, the Crimea, the Arctic, Syria) in a continuous manner is a piece of Russian strategy to avoid NATO forces operations in the NATO border states and in the areas assessed by Moscow as their strategic ones.

NATO nations should develop a common strategy and invest in resources and weapons systems that could break A2AD systems i.e. standoff weapons. The air forces of NATO members acquiring a large number of small and rather cheap unmanned ships, which could pretend combat aircraft (miniature air-launched decoy, MALD) to misguide and neutralise anti-missile systems, may be an exciting solution. In this scope, NATO needs to consider developing capabilities in fighting against A2AD in its defense planning (NDPP – NATO Defense Planning Process) [24].

6. Conclusions

In a nutshell; NATO should analyse the challenges emanating from Russian A2AD strategy to prepare itself by developing offset strategies. Effective deterrence would be very crucial to prevent Russian aggressiveness. In order to achieve and keep an effective deterrence posture; NATO should have required sophisticated capabilities, strategy and doctrine to demonstrate its ability and resolve. This requirement should inform capability development and defence planning. On the other hand; a comprehensive approach against Russian A2AD strategy is a must. All instruments of the power (e.g. political, diplomatic, economic, informational, military) should be applied coherently. Military power should be exercised jointly by including air (with space), ground and maritime forces in all domains of the operations during the peace, crisis and war.

References:

- John Keegan, Savaş Sanatı Tarihi, Çev. Selma Koçak, Doruk Yayımcılık, İstanbul 2007, p. 469.

- Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, Londra 1989, p.16.

- Jan van Tol with Mark Gunzinger, andrew Krepinevich, and Jim Thomas, AirSea Battle, A Point-of-Departure Operational Concept, CSBA, 2010, P.6.

- Ibid, p.7. ↑

- In his article in 2007, Frank Hoffman opined that “Hybrid threats incorporate a full range of different modes of warfare including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder. Hybrid Wars can be conducted by both states and a variety of non-state actors. These multi-modal activities can be conducted by separate units, or even by the same unit, but are generally operationally and tactically directed and coordinated within the main battle space to achieve synergistic effects in the physical and psychological dimension of conflict.”

- Joint Operational Access Concept, 2012, P.6. ↑

- Jan van Tol with Mark Gunzinger, Andrew Krepinevich, and Jim Thomas, Air Sea Battle: A Point-of-Departure Operational Concept, CSBA, 2010, P.18.

- Andrew F. Krepinevich, Why Air Sea Battle? CSBA, 2010, P.10. ↑

- Gustav Gressel, Russia’s Quiet Military Revolution, and What It Means for Europe, ECFR, P.10-11. ↑

- Gustav Gressel, Russia’s Quiet Military Revolution, and What It Means for Europe, ECFR, P.10-11. ↑

- Russian National Security Strategy, 2015, P.4. http://www.ieee.es/.

- Gustav Gressel, Russia’s Quiet Military Revolution, and What It Means for Europe, ECFR, P.3. ↑

- Ibid, P.4-5. ↑

- Rem Korteweg and Sophia Besch, No denial: How NATO can deter a creeping Russian threat, 09 February 2016, http://www.cer.org.uk/insights/↑

- Jan van Tol with Mark Gunzinger, Andrew Krepinevich, and Jim Thomas, Air Sea Battle: A Point-of-Departure Operational Concept, CSBA, 2010, P.19.

- Dmitry Adamsky, November 2015, Cross-Domain Coercion: The Current Russian Art of Strategy, Ifri Security Studies Center, P.39.

- Andreas Schmidt, “Countering Anti-Access / Area Denial”, JAPCC Journal 23, 27 January 2017, https://www.japcc.org/

- Guillaume Lasconjarias and Tomáš A.Nagy, “NATO Adaptation and A2/AD: Beyond the Military Implications”, 21 December 2017, https://www.globsec.org/publications/

- Nicholas Fedyk,”Russian “New Generation” Warfare: Theory, Practice, and Lessons for U.S. Strategists”, 29 August 2016, http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/

- Guillaume Lasconjarias and Tomáš A.Nagy, “NATO Adaptation and A2/AD: Beyond the Military Implications”, 21 December 2017, https://www.globsec.org/publications/

- Kathleen Weinberger, “Russian Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD) Range: August 2016“, 29 August 2016, http://iswresearch.blogspot.de/2016/08/

- Ian Williams, “The Russia – NATO A2AD Environment”, 3 January 2017, https://missilethreat.csis.org/

- Guillaume Lasconjarias and Tomáš A.Nagy, “NATO Adaptation and A2/AD: Beyond the Military Implications”, 21 December 2017, https://www.globsec.org/

- Tomasz Smura ,“Russian Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) capabilities – implications for NATO “, 27 November 2017, https://pulaski.pl/