Abstract

While the new security environment has driven the EU to take a bigger role in security and defence, it has also forced the EU-NATO relations to evolve from a desirable strategic partnership to a more ‘essential’ one, since both their security is interconnected and neither organisation has the full range of tools available to address the new security challenges on its own. Thanks to the new framework initiated by the Joint Declaration in 2016, cooperation between the EU and NATO has been gradually improving in several designated areas. But it is obvious that, within the defined framework, there are many obstacles to overcome before opportunities could be more fully exploited. While the new challenges emanated from the East and South of Europe can be seen as an opportunity for a wider cooperation, the rise of illiberalism and authoritarianism in the world, even including the member nations, poses a big challenge against the cooperation. Further concrete steps are to be taken for a wider and substantial cooperation between two Brussels-based organisations. We argue that a joint response must be formulated in the form of a common strategy, implemented in an integrated way by using a more comprehensive toolbox.

Steven Blockmans•, Hasan Suzen••, Samet Coban•••, Fatih Yilmaz••••

Keywords: NATO, EU, NATO-EU cooperation, European Defence and Security, Transatlantic Alliance, PESCO

1. Introduction

EU-NATO relations have traditionally been described in lethargic terms due to long-standing political blockages.[1] Yet bound by a shared commitment to universal values of freedom, democracy and the rule of law, NATO and the EU share not only strategic goals but also common global security challenges. In the face of rising conventional and hybrid threats and risks emanating from the southern and eastern flanks both organizations have recently vowed to strengthen cooperation to bolster resilience from disinformation campaigns and cyber-attacks; ensure coherence on conventional defence planning and coordination of exercises; stimulate R&D in the defence sector; support partners’ capacity building; and cooperate on operations in the Western Balkans, Afghanistan, and the maritime domain.[2] Whereas the most recent joint declaration of June 2018 does not seem to add much new to what the EU and NATO had already agreed to at Warsaw in 2016, the diplomatic reaffirmation masks a slow but steady inter-institutional dynamic which has largely developed below the radar.

This contribution analyses the areas in which the EU and NATO have structured their relations at headquarters level and in the field and ask how this could be further reinforced.

2. What has been achieved so far?

Until the creation of the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) at the Helsinki European Council in December 1999, the only active framework for handling specifically European security questions was the Western European Union (WEU, created by the Modified Brussels Treaty of 1954) and the special partnership of the WEU with NATO under the NATO-defined concept of European Security and Defence Identity (ESDI).[3] As NATO was hampered by the presumed restrictions on out-of-area operations, the WEU became the main enforcer of embargoes imposed by the UN Security Council during the first Iraq war (1990) and the war in ex-Yugoslavia (1991-5). For a number of years, not even a decade, the WEU acted as a bridge between the European Union and NATO and was particularly successful in drawing in the non-EU members of NATO by allowing them full participation in military activities. ‘Security through participation’ was the slogan of the day and gave the associate members, observers and associate partners a sense of belonging, as well as the opportunity to raise issues affecting their security interests.[4]

At NATO’s Berlin Ministerial meeting of 3-4 June 1996, the Alliance adopted a major document on the development of ESDI and specifically on the NATO-WEU relationship. The Berlin communiqué[5] elaborated the notion of NATO assets being provided in support of possible European defence operations led by WEU, and foresaw ongoing support by NATO for defence planning (i.e. capabilities), work and generic operational planning in the WEU framework. In the following years, a number of NATO-WEU agreements were drawn up – in all cases with Turkey’s full involvement and approval – to regulate the details of these different aspects of the ESDI partnership. In April 1999, at a time when a clear political drive was emerging for the EU to take over (in one form or another) WEU’s role as a framework for potential EU-led operations, NATO’s Washington Summit adopted a communiqué stating:

“We acknowledge the resolve of the European Union to have the capacity for autonomous action so that it can take decisions and approve military action where the Alliance as a whole is not engaged (…) NATO and the EU should ensure the development of effective mutual consultation, co-operation and transparency, building on the mechanisms existing between NATO and the WEU. [W]e attach utmost importance to ensuring the fullest possible involvement of non-EU European allies in EU-led crisis response operations, building on existing consultation arrangements within the WEU (…) the concept of using separable but not separate NATO assets and capabilities for WEU-led operations, should be further developed.”[6]

In the Strategic Concept of the Alliance, approved at the same meeting, the Heads of State agreed that NATO should

(…) on a case by case basis and by consensus (…) make its assets and capabilities available for operations in which the Alliance is not engaged militarily under the political control and strategic direction either of the WEU or as otherwise agreed, taking into account the full participation of all European Allies if they were so to choose.[7]

Against this background NATO held out the prospect of further enhancing, and in particular making more automatic, the various kinds of support developed for the WEU since the Berlin Summit of 1996 when the WEU’s relevant roles were transferred to the EU: this was the proposition that came to be known as ‘Berlin plus’.

It took four more years of intense negotiations, a significant movement in Turkey’s general relationship with the European Union, increasing pressure for the EU to take over peace operations in the Balkans from NATO and a shift of focus towards new Western-led operations outside the European arena (notably in Iraq and Afghanistan) for a breakthrough to be reached. The EU’s Copenhagen European Council of 12-13 December 2002 played a crucial part, not just by virtue of its decisions on the timing of movement towards Turkish EU accession negotiations, but also by way of its endorsement of detailed understandings including the fact that, under no circumstances, the ESDP would be used against an Ally and that Cyprus and Malta as members of the EU would not take part in any ESDP operations using NATO assets. The Turkish Government now felt able to go along with the signature of an EU-NATO Declaration at Brussels on 16 December 2002 which opened the way for the detailed development of ‘Berlin Plus’ arrangements.[8] The specifics were agreed to in March 2003 and were intended to give the EU permanent access to the planning assets of NATO, while provision of other assets would be on a case-by-case basis. The two organisations moved swiftly to open the way for the EU to take over NATO’s mission Allied Harmony in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and similar arrangements were negotiated for the takeover of SFOR in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Berlin Plus arrangements have been only being used then and are still only in place for Operation EUFOR Althea in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In view of the EU’s pre-accession conditionality vis-à-vis Cyprus, Turkey has effectively frozen the application of the Berlin Plus modalities. Yet, it may be argued that the latter framework is anyway no longer sufficient to address the new strategic needs faced by the overlapping 80% of the membership (22 states). Indeed, there have been other channels of cooperation between the two organisations, although generally with less than expected efficiency (see below).

While the new security environment has driven the EU to take a bigger role in security and defence, it has also forced the EU-NATO relations to evolve from a desirable strategic partnership to a more ‘essential’ one, since their security is interconnected and neither organisation has the full range of tools available to address the new security challenges on its own. This new narrative was peddled by the Joint Declaration on 8 July 2016 during the NATO Warsaw summit, which starts with the statement “We believe that the time has come to give new impetus and new substance to the EU-NATO strategic partnership”.[9]

EU and NATO leaders had negotiated this arrangement down to the wire of the July 11–12 Brussels Summit. The Joint Declaration was signed by NATO’s Secretary-General, Jens Stoltenberg, with Donald Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker, presidents of the European Council and the European Commission, respectively, on July 10. The document confirms NATO as the primus inter pares on defence: “NATO will continue to play its unique and essential role as the cornerstone of collective defence for all Allies”. At the same time, “EU efforts will also strengthen NATO, and thus will improve our common security.” While NATO and the EU encourage member states that belong to only one of these organisations to participate in the initiatives of the other, each organisation retains its decision-making autonomy. To promote peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area, the 2016 Joint Declaration outlined seven concrete areas (topics) where the bilateral cooperation ought to be enhanced:

- Countering hybrid threats,

- Operational cooperation including at sea and on migration,

- Cyber security and defence,

- Defence capabilities,

- Defence industry and research,

- Exercises,

- Supporting Eastern and Southern partners’ capacity-building efforts.

Subsequently, the EU and NATO established a common set of 42 actions to implement all seven areas of cooperation mentioned in the joint declaration.[10] The set also introduced a monitoring mechanism to review progress on a biannual basis. So far, three progress reports have been issued. The first, of June 2017[11], highlighted the overall expanded bilateral dialogue in the designated areas through several newly established mechanisms for interaction, information sharing and coordination. The second progress report[12] in December 2017 outlined specifics in implementing the common set of actions. An additional set of 34 actions was endorsed on 5 December 2017 including on 3 new topics: counter-terrorism; military mobility; women, peace and security. The third progress report in May 2018 elaborated on the main achievements and highlighted the added value of EU-NATO cooperation in different areas aimed at strengthening the security of citizens, outlining the significant steps taken for improving the military mobility of troops and equipment, common preparedness for cyber and hybrid attacks, fighting terrorism and fighting migrant smuggling and trafficking in the Mediterranean.[13]

Obscured by US President Trump’s theatrics at the first summit held at NATO’s new headquarters in Brussels, a second Joint Declaration on EU-NATO cooperation was adopted on 10 July 2018.[14] In the shadow of an aggressive American push towards a more equal burden-sharing and Trump’s claims that allies should increase defence spending to an incredible 4% of their GDP, the joint declaration emphasised “coherent, complementary and interoperable” capability development and encouraged the fullest possible involvement of non-EU allies in the European Union’s new initiatives in the field of defence (see below, Section 3). The final communiqué of the NATO Summit pointed to the tangible results achieved so far in a range of areas such as countering hybrid threats, operational cooperation including maritime issues, cyber security and defence, exercises, defence capabilities, defence industry and research.[15]

In terms of achievements, one cannot help but noting that, so far, most of the low-hanging fruits have been picked. A European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats has been set up in Helsinki; frequent contacts at working level and staff-to-staff communication has been achieved between the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell, the NATO Hybrid Analysis Branch and the Centre of Excellence, but trilateral cooperation has so far been based only on open source material. Information and intelligence sharing between the two partner organisations still remain a great challenge. Cyber security and defence is one of the areas where NATO and the EU are working more closely together than ever. Analysis of cyber threats and collaboration between incident response teams is one area of further cooperation; another is the exchange of good practices concerning the cyber aspects and implications of crisis management.[16] Another significant achievement is in the area of defence capabilities concerning the improvement of military mobility. This initiative, which is being catalysed by the EU in the form of a ‘PESCO’ project (cf. Section 3), aims to tackle the regulatory, procedural and infrastructural problems at borders within the EU. The results of this project will be of great importance for NATO too in terms of facilitating its operational planning and increasing its readiness and responsiveness. Of course, preventing project duplication and avoiding competition over member states’ resources continue to be major concerns.

As a sub-conclusion, it is worth observing that cooperation between the EU and NATO has been gradually improving in designated areas. It is obvious that, within the defined framework, there are many obstacles to overcome before opportunities could be more fully exploited (cf. Section 4). Yet, the emergence of the EU as a stronger defence and security actor might spur further cooperation.

3. The emergence of the EU as a military actor[17]

Lack of political will and mutual trust among EU member states has long been an obstacle to cooperation in security and defence. In the years of austerity that followed the financial crisis, defence budgets all over Europe were slashed in an uncoordinated manner, hollowing out most member states’ armies.[18] Facing a fraught security climate in the Arab world, the heads of state or government meeting at the December 2013 European Council decided to buck the trend. For the first time since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, they held a thematic debate on the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in which they declared that ‘defence matters’:

“Today, the European Council is making a strong commitment to the further development of a credible and effective CSDP, in accordance with the Lisbon Treaty and the opportunities it offers. The European Council calls on the Member States to deepen defence cooperation by improving the capacity to conduct missions and operations and by making full use of synergies in order to improve the development and availability of the required civilian and military capabilities, supported by a more integrated, sustainable, innovative and competitive European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB). This will also bring benefits in terms of growth, jobs and innovation to the broader European industrial sector.”[19]

Committed to assessing concrete progress on all issues in the years ahead, the European Council invited the Commission, the High Representative (HR), the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the member states in the Council, each within their respective spheres of competence, to take “determined and verifiable steps to implement the orientations set out above”.[20]

Tapping into the political momentum generated by Russia’s assault on Ukraine, a spate of terrorist attacks on European soil,[21] citizens’ concerns over the refugee and migrant crisis, the prospect of Brexit and the unpredictability injected into US foreign policy by Donald Trump, the EU has made greater strides in strengthening defence integration in the last two years than in the six decades before that.[22] A permanent EU headquarters for non-executive (i.e. non-combat) military operations has been created and located within the European External Action Service (EEAS) in Brussels.[23] The 22 member states that are also NATO allies pledged to increase defence spending to 2% of their GDP and to earmark 20% of that sum for investment in defence capabilities.[24] A Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) mechanism will monitor the implementation of commitments on defence spending and capability development of all EU member states. The European Council has formally launched Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) for the development and deployment of defence capabilities. A European Defence Fund (EDF) has been proposed to stimulate the development of military capabilities. And the defence ministers of nine member states signed a letter of intent to establish a European Intervention Initiative (EI2).

To digest the EU’s new alphabet soup in defence cooperation, we will structure the rapid developments along three strands of implementation: the EU Global Strategy (Section 3.1), the Commission’s European Defence Action Plan (Section 3.2) and PESCO (Section 3.3). The latter will provide the bridge to a forward leaning analysis of opportunities for further EU-NATO cooperation (Section 4). If properly aligned and implemented, these four components would make headway in the creation of a ‘European Defence Union’,[25] akin to the currency and energy unions that have gone before, rather than an ‘EU army’[26] that supersedes, let alone replaces, the national ones. This is remarkable if one considers that the natural locus for member states’ defence cooperation remains within NATO.

3.1. Implementation of the EU Global Strategy

The Union’s mixed performance in external action in the five years following the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty was a vivid reminder of the importance to endow the Treaty’s sanguine worldview of yesteryear with a new vision for the increasingly complex, connected and contested world of tomorrow. The EU Global Strategy of June 2016 did just that.[27] As a sign of the times, the tone of the document is defensive; the first priority (‘The security of our Union’) is fleshed out in most detail; and the High Representative was immediately tasked to draw up an Implementation Plan on Security and Defence (IPSD).[28] This plan formed part of a wider ‘winter package’[29] which was adopted later in 2016 and included the follow-up to the EU-NATO Warsaw Declaration and the Commission’s European Defence Action Plan.

The IPSD proposes a ‘new level of ambition’ for a stronger union in security and defence that centres around three mutually reinforcing priorities: raising CSDP’s awareness and response capacities to external conflicts and crises in an integrated manner; strengthening CSDP’s ability to build capacities of partners and thus systematically increase their resilience; and protecting the EU and its citizens by tackling threats and challenges through CSDP, in line with the Treaty, along the nexus of internal and external security.

Central to the IPSD is the deepening of defence cooperation among member states in order to deliver the required capabilities. This ambition, it is argued, adds to the EU’s credibility vis-à-vis partners:

“Europe’s strategic autonomy entails the ability to act and cooperate with international and regional partners wherever possible, while being able to operate autonomously when and where necessary. (…) There is no contradiction between the two. Member States have a ‘single set of forces’ which they can use nationally or in multilateral frameworks. The development of Member States’ capabilities through CSDP and using EU instruments will thus also help to strengthen capabilities potentially available to the United Nations and NATO.”[30]

Reinforcing this drive towards ‘strategic autonomy’ and higher levels of complementarity with international partners, the European Council of December 2016 called for deeper intra-EU cooperation in the development of the required capabilities as well as committing sufficient additional resources; all in keeping with national circumstances and legal commitments.[31] For the 22 EU NATO members this endeavour supports the commitments on defence expenditure made at Warsaw.

Thus, the heads of state or government agreed to take forward work in the European Defence Agency to translate the new level of ambition into military capability needs, revise the Capability Development Plan (CDP) accordingly, and outline capability development priorities for member states to jointly invest in. On 28 June 2018, the EDA Steering Board (in the composition of Capability Directors) endorsed the 2018 CDP and approved the associated EU capability development priorities.[32] The latter aim to contribute to increased coherence between member states’ defence planning by identifying future cooperative activities irrespective of the chosen cooperation framework,[33] including under PESCO and the European Defence Fund (cf. next sub-sections).

To help operationalise the CDP, the European External Action Service and the European Defence Agency developed proposals on the scope, modalities and content of a member-state driven Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD). The Foreign Affairs Council of May 2017 endorsed the establishment of the CARD, starting with a ‘trial run’ (from autumn 2017 to autumn 2018) in order to test, adapt and validate member states’ approach as necessary ahead of the first full CARD implementation in autumn 2019.[34] The EDA will act as CARD secretariat and present a report to its Steering Board (at ministerial level). This report, which is forwarded to the Council, will provide an overview of:

“(i) Member States’ aggregated defence plans, including in terms of defence spending plans taking into account the commitments made by the European Council in December 2016, (ii) the implementation of the EU capability development priorities resulting from the CDP while considering also prioritization in the area of Research & Technology and Key Strategic Activities, and (iii) the development of European cooperation; providing over time a comprehensive picture of the European capability landscape in view of Member States identifying the potential for additional capability development.”[35]

Such a review of member states’ implementation of CDP priorities should help “foster capability development addressing shortfalls, deepen defence cooperation and ensure more optimal use, including coherence, of defence spending plans.”[36] For those member states participating in PESCO, an annual assessment of progress towards attainment of their commitments should draw to the maximum extent possible on information provided under the CARD exercise. The CARD system is thus designed to encourage EU member states to synchronise their defence budgets and capability development plans. Greater transparency, visibility and political commitment should allow the EDA and the Council to identify opportunities for joint projects in capability development and deployment, and to create peer pressure to spend more on defence – for NATO Allies up to the level of 2% of GDP agreed at Wales. Yet, the CARD would be implemented on an entirely “voluntary basis and in full respect of Member States prerogatives and commitments in defence including, where it applies, in collective defence and their defence planning processes and taking into account external threats and security challenges across the EU.”[37] For the CARD to provide real added value, according to the EDA, it would need to rely on the collection of the most up-to-date and detailed information possible of member states’ defence (spending) plans and implementation of the capability development priorities. The CARD system therefore depends on trust among the member states, which historically has been in short supply. As in the early days of the operation of the semester system in the Eurozone, it is not entirely clear how, short of the diplomatically unfriendly act of suspending a member state from PESCO, compliance with the commitments will be ensured, let alone enforced in cases when peer pressure does not suffice.

What is clear though is that the future European Defence union will require member states’ joint development, acquisition and retention of the full-spectrum of land, air, space and maritime capabilities. In this respect, the EU Global Strategy identifies a number of priority areas for joint investment and development: intelligence-surveillance reconnaissance, remotely piloted aircraft systems, satellite communications and autonomous access to space and permanent earth observation; high end military capabilities including strategic enablers, as well as capabilities to ensure cyber and maritime security (EUGS, 48). But for the Union to be able to deliver on these capability priorities and enhance its strategic autonomy, it needs to create the conditions for more efficient and output-driven defence cooperation. This implies a more innovative and competitive industrial base. These are the main drivers of the Commission’s European Defence Action Plan.

3.2. European Defence Action Plan: market, industry and funding

The European defence market has traditionally suffered from fragmentation and low levels of industrial collaboration. Years of austerity have exacerbated this trend, thereby jeopardising not just the sustainability and competitiveness of the Union’s defence industry but also the strategic autonomy of the EU. Studies have shown that, especially at a time of budgetary constraints, a more efficient use of public money could be achieved by reducing unnecessary duplications, targeting projects that surpass individual member states’ capacities to undertake, and improving the competitiveness and functioning of the single market for defence.[38]

In an effort to support Europe’s defence industry and the entire cycle of capability generation, from research and development to production and acquisition, the Commission launched its European Defence Action Plan (EDAP) at the end of November 2016.[39] Given that the decision to sustain investments and launch capabilities development programmes in the realm of defence remains the prerogative of the member states, the Commission considers that it can, within the limits of the Treaties, only “complement, leverage and consolidate” member states’ joint efforts in this field.

As noted earlier, this is not the first time that the Commission launches a strategy to support competitiveness of the European defence industry and the creation of a more integrated defence market. Yet, the adoption in 2009 of two directives, one simplifying the terms and conditions of transfers of defence-related products,[40] and the other on the coordination of procedures for the award of certain works contracts, supply and service contracts by contracting authorities or entities in the fields of defence and security,[41] have not contributed much to the progressive establishment of a European defence market. Intended to manipulate the supply side of the defence market, they contain loopholes that allow member states to invoke essential interests of its security to continue their protectionist practices of licencing and procuring domestically. Government-to-government sales and 100% R&D contracts are also excluded from the directives’ provisions. The EDA calculated that in 2014, 77.9% of all equipment procurement took place at the national level, thereby depriving countries of the cost savings that come with scale.[42] Yet, in its own evaluation, the Commission declared the two directives “broadly fit for purpose” and therefore not in need of legislative amendment.[43] But acknowledging the untapped potential of the EU procurement rules, the Commission proposed to push ahead with what it calls an “effective application” of the two directives, “including through enforcement.”

The big bazooka, proverbially speaking, is the launch of a European Defence Fund (EDF) through which the Commission plans to bring adult money online to support capability development and the European defence industry.[44] The EDF introduces a specific line through which the Commission can tap into the EU’s general budget to finance initiatives in the field of defence. Generally speaking, budget is policy. The plan to earmark more than €1.5 billion per year after 2020 to spend on military R&D is ground-breaking.[45] However, the final sum is conditional on a future agreement on the EU’s post-Brexit multiannual financial framework (MFF). If the proposal passes all negotiations unscathed then approximately €500 million per year will be made available through the ‘research window’ of the fund. This would make the EU the fourth biggest investor in defence research in Europe, after the UK, France and Germany.[46] Through the ‘capability window’ around €1 billion would be spent annually on development and acquisition.

The mobilisation of EU funds is not intended to be a substitute for low levels of investment in defence by member states. The Commission has opted for a co-financing mechanism, generally taking on 20% (with a 10% bonus for applicants hailing from the 25 member states participating in PESCO) of the financial burden of legal entities (i.e. research institutes and companies) in the R&D phase.[47] The Commission hopes that by providing such a top-up, it will incentivise member states to invest larger sums.[48] However, states participating in the first batch of PESCO projects have budgeted them without counting on the bonus. Also, the potential to “turbo boost”[49] defence spending is likely to be restricted to EU-level initiatives that do not threaten national industries or local jobs, where transnational responses are required to meet current and future challenges, and where shortfalls are, relatively speaking, the biggest. The training, capability development and operational readiness of military prototypes, such as a European drone, a European cyber shield, and medical command come to mind.

For the EDF to succeed in addressing some of the underlying problems that weaken the European defence technological and industrial base it is crucial that the collaborative projects developed in the experimental phase add real value at EU level. In view of global supply chains in defence, the eligibility for EDF grants should probably go beyond the EU. There exists a legal opening for this. Already now projects need to be developed by at least three legal entities from two member states or one plus Norway.[50] From 1 January 2021 onwards, the eligibility criteria will be scaled up to broaden cooperation across Europe and overseas countries and territories. The draft Regulation establishing the EDF prescribes that funding will only be made available if the action is undertaken in a consortium of “at least three legal entities which are established in at least three different Member States and/or associated countries.”[51] Associated countries are defined as members of the European Free Trade Association which are members of the European Economic Area (EEA), in accordance with the conditions laid down in the EEA agreement. Legal entities which are physically located on the territory of or subject to control by non-associated third countries or non-associated third country entities are in principle excluded from European defence funding. Given the United Kingdom’s notified intention to withdraw from the EU, the Regulation was drafted for a Union of 27 member states. Companies and research institutes from the UK would thus in principle not be eligible for EDF grants. The latter also applies to the United States and other NATO Allies. Yet, in view of the specificities of cross-border defence markets and integrated supply chains, the desire to continue industrial cooperation with UK entities after Brexit, and heavy pressure exerted by the United States,[52] the Commission has introduced a narrow derogation from the rule, stating that funding may be awarded to an non-associated country applicant “(…) if this is necessary for achieving the objectives of the action and provided that its participation will not put at risk the security interests of the Union and its Member States”.[53] Applications for EDF grants will be assessed on the basis of award criteria which put fostering excellence, innovation and the competitiveness of the European defence technological and industrial base front and centre. By incentivising joint R&D of products and technologies in the area of defence, the EDF is therefore expected to increase the efficiency of public expenditure and contribute to the overriding aim of enhancing the Union’s strategic autonomy.

3.3. PESCO

The final and binding element of the EU’s new alphabet soup is PESCO – permanent structured cooperation. While the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) identifies opportunities to plug shortfalls and the European Defence Fund (EDF) stimulates the European defence technological and industrial base by investing in cross-border capability development, PESCO facilitates the build-up and operationalisation thereof.

Of all policy fields which fall within the framework of the European Union’s non-exclusive competences, the provisions on PESCO amount to “the most flexible template” of enhanced cooperation.[54] Article 42(6) TEU foresees the creation of a permanent structured cooperation between willing member states “whose military capabilities fulfil higher criteria and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area with a view to the most demanding missions”. This provision encapsulates the raison d’être of PESCO: participating states commit to spend more, and more intelligently, on better defence equipment so that they are better able to conduct operations at the higher end of the military spectrum. The Treaty gives no clear answer whether PESCO will therefore prepare the EU member states to engage in kinetic, i.e. war-like, operations against an identified enemy.[55] Article 1(b) of Protocol No. 10 attached to the Treaties does spell out that any member state wishing to participate in PESCO should:

“have the capacity to supply (…) targeted combat units for the missions planned, structured at a tactical level as a battle group, with support elements, including transport and logistics, capable of carrying out the tasks referred to in Article 43 (TEU), within a period of five to 30 days, in particular in response to requests from the (UN), and which can be sustained for an initial period of 30 days and be extended up to at least 120 days.”

As such, the Protocol codifies the ‘2010 Helsinki Headline Goal’, which set up a rotating system of multinational force packages of at least 1,500 military personnel capable of responding rapidly to conflicts across the entire spectrum of crisis management.[56] PESCO may thus blow new life into the fledgling concept of ‘EU battlegroups’, which reached full operational capability on 1 January 2007 but have never been deployed. Arguably, this is not due to a lack of crises to respond to but primarily because the bulk of the costs of deployment (both human and financial resources) would fall on those governments who happened to be on rotation – something which member states ‘on standby’ could veto in the Council.[57] Article 2 of Protocol No. 10 tries to tackle this issue by requiring PESCO states to “(c) take concrete measures to enhance the availability, interoperability, flexibility and deployability of their forces, in particular by identifying common objectives regarding the commitment of forces, including possibly reviewing their national decision-making procedures”. In this context, the European Council of December 2013 already called for the ‘rapid’ re-examination of the ‘Athena mechanism’ for financing common costs of EU military missions and operations. Four years later, the European Council reiterated its request for a revision, which had been scheduled for the end of 2017. An ambitious expansion of the financing of such operations would, indeed, make sense: “countries contributing to EU battlegroups should not face crippling bills just because they happen to be on duty.”[58]

On top of the entry criteria for PESCO laid down in Article 1 of Protocol No. 10, i.e. proceeding more intensively to develop defence capacities and having the capacity to supply troops and kit, Article 2 adds the following baseline commitments for continued participation in the structured framework: (a) cooperating with a view to achieving higher levels of investment expenditure on defence equipment in the light of, inter alia, international (esp. NATO) responsibilities; (b) aligning the defence apparatus by identifying military needs, pooling and specialising capabilities, and encouraging cooperation in training and logistics; (c) taking concrete measures to mobilise forces; (d) reducing capability shortfalls and gaps; and (e) participating in major joint or European equipment programmes in the framework of the EDA.

Despite early attempts by Belgium, Hungary and Poland in a 2010 non-paper of their Trio Presidency to outline some thoughts on how cooperation might be made inclusive and effective,[59] and a written request by Italy and Spain to HR/VP Ashton in May 2011 to put PESCO on the agenda of the Foreign Affairs Council, it took until June 2016 for a High Representative to suggest in the EU Global Strategy that “(e)nhanced cooperation between Member States should be explored, and might lead to a more structured form of cooperation, making full use of the Lisbon Treaty’s potential” (EUGS, 48). The December 2016 European Council responded by tasking the HR and the member states to present “elements and options for an inclusive Permanent Structured Cooperation based on a modular approach and outlining possible projects.”[60] Throughout 2017, the EEAS and EDA worked with member states to hammer out the principles, commitments and governance of PESCO.

As a first formal step, 23 willing and able member states signalled their intention to the Council and the High Representative to participate in PESCO by signing a joint notification on 13 November 2017.[61] The 10-page notification outlines:

- the principles of the PESCO, in particular that the “PESCO is an ambitious, binding and inclusive European legal framework for investments in the security and defence of the EU’s territory and its citizens”;

- a list of 20 “ambitious and more binding common commitments” that the member states have agreed to undertake, including “regularly increasing defence budgets in real terms in order to reach agreed objectives”; and

- proposals on PESCO governance, with an overarching level maintaining the coherence and the ambition of the PESCO, complemented by specific governance procedures at projects level.

After having consulted the HR, a list of 25 member states participating in PESCO was adopted by the Foreign Affairs Council within the statutory limit of three months.[62] Ireland and Portugal joined the initial group of 23 countries after their respective parliaments gave their consent, while Denmark (which has an opt-out from CSDP), Malta (which invoked a constitutional commitment to neutrality and non-alignment but kept the door open for future participation depending on the course of implementation) and the UK (which is leaving the EU) chose to stand aside. In their capacity as ‘member states’, these countries could still notify their intention of joining PESCO, but only if and when they fulfil the entry criteria and make the required commitments.[63] As a third state,[64] the UK could get involved in PESCO projects if it provides “substantial added value” and contributes financially. Depending on the terms of Brexit, the UK might be eligible to receive European defence funding if it qualifies as a (non-)associated country.[65]

Council Decision (CFSP) 2017/2315 establishing PESCO was adopted by consensus and the European Council “welcome(d) the establishment of ambitious and inclusive permanent structured cooperation.”[66] Those with vested interests ratcheted up the language in an attempt to claim ownership of the “historic”[67] “first operational steps towards a European Defence Union.”[68] Yet the political rhetoric surrounding its launch, including misperceptions about the enforceability of the “legally binding framework” of PESCO, with packs “20 legally binding commitments” aimed at taking the participating states by 2025 to a higher level to perform all crisis management tasks listed in Article 43 TEU, has raised expectations that the EU may not be able to meet. For PESCO to succeed, it will need to overcome at least three key challenges: raising the level of ambition while ensuring inclusivity (see below); maintaining credibility in case member states do not comply with their commitments; and ensuring coherence with the many other building blocks in Europe’s defence architecture, in particular NATO (see Section 4).

The tension between inclusivity and level of ambition is key. PESCO has so far produced the most inclusive expression of enhanced cooperation, even if it is the most flexible of differentiated integration mechanisms provided by the Treaties. This is largely the result of a German push for inclusivity which prevailed over a French desire for a higher level of ambition. Paris wanted high (NATO-level) entry criteria that would allow a military vanguard of only the top European military powers with the same strategic culture to join in carrying out operations at the upper end of the military spectrum. In line with its post-WW2 culture of military restraint Germany did not want to create any binding formats that would force expeditionary warfare upon the Bundeswehr. Berlin was also opposed to creating additional divisions with Central and Eastern European countries. But rather than presenting their views as a binary choice to the other member states, Berlin and Paris agreed to a compromise by applying a ‘modular approach’[69] to enhanced cooperation in the field of defence.[70] Instead of creating a two-speed Europe at the level of the Common Security and Defence Policy, a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model has been agreed to the PESCO mechanism within CSDP; one whereby decision-making by unanimity at the level of the Council (the hub) guarantees inclusivity while at the same time allowing different consortia of member states to pioneer projects (the spokes) in order to raise the level of ambition overall.[71] Paradoxically, the modular approach to structured cooperation also serves as a permanent vehicle for opt-outs and exemptions in the area of defence. For PESCO to succeed, the key challenge, therefore, is “to develop a modus operandi (which is) flexible (enough) to manage diversity (and) solid (enough) to generate tangible collective gains.”[72]

There are two reasons for concern, however. First, in spite of the low threshold for launching PESCO (by QMV), decisions and recommendations taken within the framework are adopted by unanimity, constituted by the votes of the representatives of all participating member states. The likelihood that the participating states would adapt the governance rules for individual PESCO projects so as to take decisions by QMV is close to zero. As a result, decision-making by unanimity will prolong consensus politics and mean that the speed of European defence cooperation and integration is determined by the slowest wagon in the train. Poland may well replace the UK as the member state that most frequently slams on the brakes. In the face of Russian aggression, the country relies on the hard security guarantees provided by the US. Warsaw has long resisted the idea of EU defence integration for fear of undermining NATO’s resolve to come to the rescue in the hour of need. Political market forces unleashed by the prospect of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump have ultimately led the Polish government to sign up to PESCO, no doubt driven by the thinking that ‘if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em’. Rather than being left at the station, Poland jumped on Europe’s defence train, expecting that, once aboard, it would be able to slow it down and even change the direction of travel.[73]

A second reason for concern is that the first batch of 17 PESCO-branded projects concern mostly the implementation of off-the-shelf plans, i.e. existing EDA and NATO projects such as cooperation on a European secure software defined radio, upgrading maritime surveillance, creating a ‘deployable military disaster relief capability package’ and setting up a ‘network of logistic hubs in Europe and support to operations’.[74] Military mobility, the most populated project (all PESCO states minus Ireland), is another example. Developed within NATO and refined in the PESCO framework, the project has been referred to as the ‘Schengen of defence’.[75] Yet, rather than creating a free-travel zone for European armies (or a visa-free travel area for third country troops for that matter), the project merely aims to facilitate the cross-border movement of troops, services and goods (e.g. for military exercises) by harmonising rules (e.g. customs, dangerous goods, trans-European transport networks) and procedures between participating states.[76] Whereas the upward convergence of legal standards and requirements in the areas where projects are developed is certainly welcome, critics have argued that the 17 PESCO projects stop short of developing the defence capabilities that would endow the EU with the strategic autonomy aspired to, for instance a European military transport helicopter, a maritime patrol aircraft, air-to-air refuelling capacities, the next generation of satellite communications, and a high-altitude long endurance drone.[77] Similarly, the EU Global Strategy’s Implementation Plan on Security and Defence currently does not specify how many operations the EU has to be able to conduct simultaneously, only that “a number of [these] may be executed concurrently”.[78] Nor does it give any indication of the envisaged scale of these operations. In fact, the plan limits the scale by stating that the EU should be capable of these operations based on “previously agreed goals and commitments”, i.e. the existing Headline Goal. An update by the EU Military Staff of five illustrative scenarios that drive the identification of military requirements have fed into the June 2018 update of the Capability Development Plan by the European Defence Agency without, however, going beyond the 2010 Headline Goal.

This raises the question of whether projecting unity was more important to the architects of PESCO than using up the single opportunity to activate a unique Treaty basis that would have allowed for a greater level ambition with a smaller group of states whose military capabilities fulfil higher criteria. In a move widely seen to be a response to an overly inclusive and underambitious PESCO, France – after Brexit the only EU member state with a nuclear and expeditionary force capacity – has been actively preparing the European Intervention Initiative (EI2) proposed by Emmanuel Macron in his Sorbonne speech in September 2017. Beyond the facade of creating a common strategic culture and European strategic autonomy, the EI2 is primarily about preparing a group of able and willing countries for joint military interventions in the EU’s neighbourhood without prejudice to the EU, NATO or any other institutional framework.[79] The latter is underlined by the fact that the UK (which is leaving the EU) and Denmark (which has an opt-out of CSDP) have joined the initiative,[80] and that EI2 will be “resource-neutral”.[81] However, the potential for duplication, in particular with PESCO’s German-led ‘EUFOR Crisis Response Operation Core (EUFOR CROC)’ project, is real. While stressing the “need to further develop the emergence of a shared strategic culture through the European Intervention Initiative” in their Meseberg Declaration of 19 June 2018, French President Macron and German Chancellor Merkel agreed to link EI2 “as closely as possible with PESCO.”[82] For that to happen, the associate status for the respective non-members is essential, as well as the need to fill PESCO with real substance. For the EU to attain strategic autonomy, the next batch of PESCO projects ought to substantially raise the level of ambition — whilst not competing or duplicating, but complementing NATO efforts.[83]

4. Increasing need for a wider EU-NATO Cooperation

As acknowledged by both organisations, the EU and NATO have an increasing need for a wider and more efficient cooperation to tackle new and shared strategic challenges. These strategic challenges emanate from both the Eastern Flank – mainly the Russian aggression starting with its annexation of Crimea – and the Southern Flank. The latter includes a combination of state and non-state actors ranging from Russia’s anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) build-up; Iran’s ballistic-missile proliferation; terrorist, radical and violent non-state groups; fragile states suffering from extreme inequality in the distribution of income and democratic deficit; and uncontrolled migration. With all these newly emerged challenges, the current strategic environment could be seen as an opportunity for a wider cooperation.

Although the efforts for a wider EU-NATO cooperation have been strengthened in the wake of the Joint Declaration in 2016 and the adoption of 42+34 actions in 7+3 defined areas, the improvements achieved so far are more on the bureaucratic than on the operational side. It has become obvious that a wider cooperation is hampered by the unilateralist tendencies by the administration of US President Trump, increasing authoritarianism and illiberalism among member states, different views and policies to tackle strategic challenges, and BREXIT. Then again, the upward trend in member states’ defence spendings may, if managed well and in a complementary fashion, generate new opportunities for enhanced cooperation.

4.1. New Challenges on the Eastern and Southern Flank

There is a widespread acceptance that recent developments have raised concerns about the resilience of the liberal international order established in the aftermath of World War II. In light of the 2018 Munich Security Report[84] one could hold that the main threats emerging in recent decades to the liberal order are: an abdication by the United States from its leading role in the liberal world order; the protracted crises affecting the EU, which has a long way to become a global actor; Russian aggression using primarily hybrid tactics; and Chinese economic dominance. The threats align with the decline of liberal democracy and civil liberties, the rise of nationalism and populism, erosion of the role of international institutions and agreements, and finally the rise of defence spending in many parts of the world. We will discuss some of these in turn.

4.1.1The Eastern Flank

Analysis of the origins and the evolution of Russian aggression reveal that the current Russian way of war, using hybrid methods in sync with military means,[85] asks for a holistic, harmonised approach that comprises political, economic, humanitarian, informational, and other non-military instruments.[86] In his speech at the Valdai International Discussion Club’s annual meeting in 2014, President Putin argued that “the Western system of order threatens Russian interests” and that if existing international relations and law got in the way of these interests, that order would have to yield.[87] Seen from the Kremlin, therefore, EU and NATO enlargement in the post-Soviet “buffer-zone” are threatening Russia’s interests.

On the back of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, Russian aggression against Ukraine has proved to be a turning point in pan-European relations. In the months following violent ‘Euromaidan’ protest in Kyiv, masked Russian Special Forces and Russian backed para-military groups, referred to by the international media as “little green men”, seized government buildings and key infrastructure in Crimea. In reality, this de facto invasion was not a surprise, but a deliberate and long-term political warfare strategy directed by the Kremlin.[88] This Soviet-style disruption used “masked warfare” with the addition of computers, social and mass media, and deception operations paralysed the Ukrainian government and the international community, which could take no action.[89] Furthermore, Russia conducted cyber-attacks against Ukraine,[90] organised pro-Russian Ukrainians to terrorise Eastern Ukraine.[91] The Kremlin manipulated the outcome of a referendum on self-determination which produced scant legitimacy for the annexation.[92] Moscow played the energy card at every opportunity by exploiting Ukraine and Europe’s dependency on Russia.[93] Russia also exported instability to Ukraine through the use of economic warlords, mafia, and criminals whose origins are linked to the late-Soviet era black market.[94] As such, Russia created an opportunity for itself to turn away from the West. Russia’s involvement in Syria and rapprochement with Turkey have cemented this radical departure from the pursuit of closer relations with NATO and the EU under Putin’s first term.[95]

Russian aggression now affects the Western security and stability in three ways: it destabilises the global security status quo and liberal international order; it threatens the EU’s and NATO’s solidarity and cohesion and undermines their roles in the international system; and it sets an example for other possible adversaries how political warfare could be a valuable and effective way to target liberal democracies without triggering any armed conflict.[96]

Subsequent crises, for instance over the poisoning of an ex-spy in the UK with weapon-grade novichok, have heightened tensions further. Some argue that despite tough rhetoric, the steps taken so far constitute a weak response from the UK. On the other hand, some have concerns about the return of cold war mentalities and hostilities without clear rules of the road,[97] and without – less so for NATO but more for the EU – proper channels of communication, as they were mostly cut following the war in Ukraine crisis. France has pursued a balancing act between Russia and the West. With a more self-assured Russia under Putin, to some extent, such an approach could be seen as a challenge for the EU and NATO as well.[98] Despite ongoing tensions between the West and Russia over Syria and Ukraine, visits at presidential level and the Franco-Russian Economic, Financial, Industrial and Trade Council (CEFIC) periodic meetings have continued since January 2016. Since coming to office, President Macron has tried to improve relations with his Russian counterpart, particularly in coming up with a sustainable solution to the war in Syria.[99] The relationship between Germany and Russia is officially still one of ‘strategic partnership’, enhanced by a ‘modernisation partnership’.[100] Irrespective of the war in Ukraine and the attempted assassination of double agent Skripal, Russia seems to have been able to count on Berlin’s “strategic patience” and strengthen its ties in the realm of energy security.[101] Italy has also special relations with Russia based on historical ideological sympathies, geostrategic calculations, commercial interest, energy dependence, and personal relationships between leaders.[102] Italy’s Prime Minister Conte emphasised his government’s commitment to dialogue with Russia, with an intention to review the EU sanctions policies over Ukraine.[103] Key EU member states have thus followed a kind of re-balancing behaviour while increasing their ‘unified defence’ capacity.[104]

We can summarise NATO’s (and also the EU’s) actions in Table 1.

| Actions and Counteractions | Overt Direct | Overt Indirect | Covert Direct | Covert Indirect |

| NATO Counteractions |

– Strategic Communication (The NATO-Russia Council meetings) – Assurance measures in Eastern Europe and Turkey * Mil exercises for deterrence * Enhanced forward presence * NATO’s VJTF[105] – Suspension of all practical cooperation with Russia |

– Alliance cohesion – Partnership with the countries in Russian buffer-zone |

– Cyber defence | – ? |

| EU Counteractions |

– Strategic Communication – Public diplomacy – Economic sanctions – Frozen policy dialogues and mechanisms of cooperation (Partnership and Cooperation Agreement) |

– EU-Ukraine AA/DCFTA[106] – Lifting arms embargo on UKR – Common External Energy Policy |

– Diplomatic support to legal governments – Cyber defence |

– ? |

Table 1: Comparison of NATO and EU Counteractions Spectrum (Suzen, 2018).

4.1.2. The Southern Flank

The Southern flank poses a series of threats and risks to both the EU and NATO, with protracted and varied challenges from a combination of state and non-state actors. They range from Russia’s anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) build-up; Iran’s ballistic-missile proliferation; terrorist, radical and violent non-state groups; fragile states with extreme inequality in the distribution of income and democratic deficit; population flows and uncontrolled migration. [107] It is obvious that to counter these elements of the threat landscape calls for a robust response which should include multidimensional strategies and combination of efforts of the two organisations.

In light of these challenges, the EU and NATO have enhanced the coordination of their crisis management and capacity-building actions, for instance through surveillance operations, interventions against terrorist groups, or maritime security and border protection missions.[108] By expanding military cooperation with regional partners, NATO and the EU should cooperate in security sector reform and defence capacity-building (DCB) in order to strengthen migration control, maritime security and counterterrorism. The two organisations would also need to enhance maritime and air assets in and around the region with a stronger focus on A2/AD, stronger intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. When it comes to preventing the flow of foreign fighters and radicalised terrorists, the EU has already taken significant steps to increase systematic checks at its Schengen borders. NATO’s position could be in training local forces in terrorist hotspots.[109]

As a result of the Putin-Brexit-Trump factor, items related to the Southern Flank have been downgraded to a “lower priorities” status on the agenda of both organisations.[110] Furthermore, some NATO states, such as France, have argued that, due to limited diplomatic capacity of the Alliance, NATO should concentrate on its initial purpose — defending its territories — rather than engaging with MENA region.[111] In such an environment, neither NATO nor the EU is able to engage all MENA partners simultaneously and address all threats and risks individually. Moreover, reduced Western influence – accelerated by the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, fall-out from NATO’s Operation Unified Protector in Libya, and the “America First” approach of the Trump Administration – has caused a power vacuum[112] that has enabled outsiders like Russia, ill-minded regional powers like Iran, or terrorist/radical groups to fill this gap.

In this regard, wider EU-NATO cooperation focus should shift towards partners’ specific needs especially. These include: security sector reform and defence institution building, civilian control of armed forces, enhanced capacity building in inter-operability, joint and multinational operations for countering hybrid threats, terrorism, and humanitarian aid.

4.2. Increase in defence budgets

Since Donald Trump has taken on the presidency in the U.S., fair burden-sharing has moved to the top of NATO’s agenda. Much ink has been spilled about increasing defence budgets, its reasons, its impacts, divergence of approaches and its potential consequences.[113] This section focuses on the core of the problem, defence expenditures, without necessarily diving into all of the details.

From the end of Cold War to the eruption of war in Ukraine in 2014 Allies enjoyed the peace dividend of the unipolar world.[114] As a consequence of the rapidly changed security environment, a rise on defence budgets has been observed. The 2014 Wales Summit formalised the commitment in concrete criteria: spending a minimum of 2% of GDP on defence and 20% of defence expenditure on the acquisition of major equipment, research and development (R&D); those who’d fail these criteria were expected to halt any decline in defence expenditure and aim to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade.[115] These guidelines were severely criticised by many for being unrealistic and ineffective.[116] A NATO Ally purchasing a $2.5bn Ballistic Missile Defence System from Russia and by so doing meeting its 2% guideline is a case in point.[117] Alternative indicators have been suggested to better reflect burden-sharing among Allies. One of the most recent works on this issue introduces different criteria such as security assistance expenditure as a share of GDP, troop contributions as a share of total active duty force, pre-crisis military mobility, trade with sanctioned competitors and average refugee intake in order to take into account different parties’ sensitivities.[118]

Prior to NATO’s 2018 Summit the Secretary General announced that in 2018, only eight Allies (U.S., UK, Greece, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia) would be able to either maintain or increase their defence spending above the 2% guideline.[119] Regarding the second metric, equipment expenditure, Allies’ performance is much better. 15 Allies currently spend more than 20% of their defence expenditures to heavy equipment. Apart from these metrics, there are some other powerful estimates of burden-sharing, in terms of defence expenditure per capita and the number of military personnel made available by NATO. Table 2 shows the latest available official data from NATO, made public at the Brussels Summit.[120] Figures are 2018 estimates in constant 2010 prices. Table 3 presents the available data on defence expenditures of non-NATO EU countries (in constant 2016 prices). Austria, Finland and Sweden are of particular importance. NATO’s Enhanced Opportunities Partners Finland and Sweden spend as much as Norway in the Baltics for defence mainly in view of the Russian threat. Austria is an important security provider in the Western Balkans.

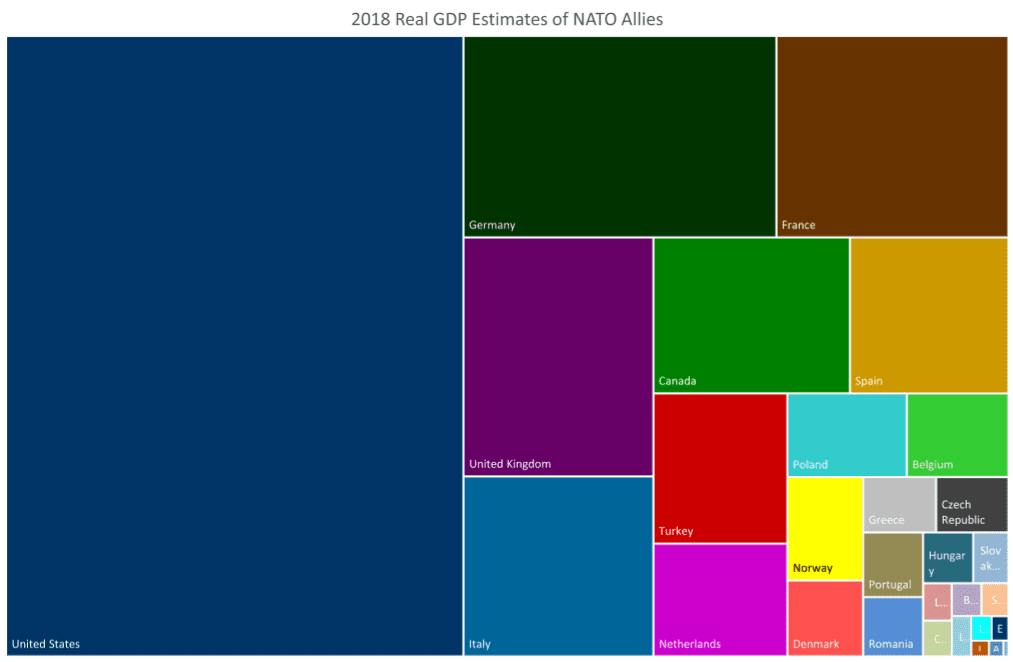

Charts 1 and 2 depict the core of the discussion and visually compare 2018 GDP and defence expenditures respectively. Cumulatively, other Allies earn more than the U.S. in terms of GDP but U.S. defence expenditure ($623.2bn) alone outweigh that of all other Allies combined ($312bn). With a combined total of $210bn, the EU member states outspend Russia, the main (potential) threat to European security, which accounts for slightly more than $46bn per year.[121] Germany’s defence budget currently stands at more than $48bn.

Table 2: Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2018 estimates)[122]

Table 3: 2016 Defence Expenditure of non-NATO EU Members[123]

Chart 1: 2018 Real GDP Estimates of NATO Allies[124]

Chart 2: 2018 Defence Expenditure Estimates of NATO Allies[125]

Table 4 compares the economic performances and the defence expenditures of the Allies between 2015-2018. In the 2% debate Europe tends to focus on the green columns, increase in defence spendings, while the U.S. understands the problem as calculated in the blue columns, putting pressure on Allies to close the gap between the 2% guideline and actual defence spending. In the last four years Allies spent an extra $40bn whereas the gap between the 2% guideline and the actual spending continues to diminish and currently stands at $476bn (Minus figures are neglected in gap calculation since a surplus in one Ally’s defence expenditure doesn’t close another Ally’s gap).

Table 4: Defence Expenditures of NATO Allies Between 2015-2018[126]

NATO’s Brussels Summit is a good indicator for future trends in defence spending. The Joint Declaration on EU-NATO Cooperation (2018) and Brussels Summit Declaration were carefully crafted, balanced and reinforced much needed solidarity among Allies. The former covers almost all important topics between EU and NATO. It describes transparency as ‘crucial’ and encourages EU and NATO to get its members that are not among the members of the other to involve in the initiatives of the other to the fullest possible extent, something to which the US attaches great importance. On the other hand, PESCO and the EDF are praised as they contribute to the safety and stability of Trans-Atlantic region with the condition that ‘the capabilities developed through the defence initiatives of the EU and NATO should remain coherent, complementary and interoperable’. The document also underlines the importance of sharing of the burden, benefits and responsibilities in accordance with Defence Investment Pledge.

The Brussels Summit Declaration’, 2018 underlines the importance of the European Union as a unique and essential partner for NATO and will continue to further strengthen our strategic partnership in a spirit of full mutual openness, transparency, complementarity, and respect for the organisations’ different mandates, decision-making autonomy and institutional integrity, and as agreed by the two organisations emphasizing ongoing cooperation efforts that substitute common set of 74 proposals.[127] Generating additional 30 major naval combatants, 30 heavy or medium manoeuvre battalions, and 30 kinetic air squadrons, with enabling forces, at 30 days’ readiness or less, or in other words NATO Readiness Initiative, offers a huge area of cooperation between NATO and the EU for countering conventional threats. As mentioned earlier, improving legislative arrangements, enhancing command and control, increasing transport capabilities, and upgrading European infrastructure to facilitate military mobility is another strand to boost cooperation between NATO and the EU. Furthermore, the Brussels Summit Declaration pointed to the establishment of new command and control entities in Europe. Two multi-corps capable Land Component Commands (LCC), a Corps-level LCC (possibly in Romania) and multinational Division Headquarters (possibly in Denmark, Estonia, Latvia) and Divisional Headquarters in support of activities envisaged by the enhanced Framework for the South on a rotational basis (Italian offer) may also invigorate the cooperation between the two organisations.

However, the 2% debate was at the centre of the discussions and spoiled the meal. President Trump publicly criticized Allies[128] and urged them to pay 2% of their GDPs to their defence ‘immediately, not by 2025’[129] which will ‘ultimately go to 4%’.[130] Unsurprisingly, Germany was at the centre of the discussions. Although increasing its defence budget steadily, Germany will be able to reach 1.5% rather than the 2% target by 2024, as agreed at Wales. The debate revealed severe combat readiness issues within the German army and raised questions among its Allies. It is not only Germany that Trump blamed. Prior to the Summit, U.S. administration sent letters to some Allies,[131] even to the ones that meet the 2% objective and asked for increasing their defence budgets. Table 4 shows that the U.S. has already dealt with or will also deal with Italy, Spain, Canada and the Netherlands because of their 2% gap in defence spending.

There are three possible scenarios for the foreseeable future:

- Allies behave as Mr. Trump wishes and boost their defence budgets to 2% overnight (least likely),

- Europeans refuse American commitment on European defence step forward to construct ‘the European pillar’ in order to counter risks and threats that they faced (most dangerous),

- Something in between (most likely). Taking the security environment into account, nations will in one way or another invest in their security. It is in European countries’ national interests to spend their money in a way to maximize the efficiency and minimize ‘unnecessary duplication’.

4.3. Strongmen: Rise of illiberalism and Authoritarianism

In the midst of an era of competition between liberal and illiberal or autocratic states, the liberal vision of the West is under strain. According to the Freedom House findings for 2018 democracy, political rights, and civil liberties are declining around the world for 12 consecutive years.[132] Trump, Putin, Erdogan, Orban and like-minded ‘strongmen’ use challenges such as terrorism, radicalism and illegal immigration to polarize societies and export these problems to their rivals to further national and more narrowly-defined causes instead of promoting liberal values and universal democratic principles and rights.

For the NATO and EU, countries represented by strongmen are of particular concern especially when they are member states. Both organizations share similar universal values in their founding acts. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilisation of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.[133] The Treaty on European Union and Charter of Fundamental Rights enshrine the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and the rule of law.[134] Paradoxically, democratic backsliding is being observed in countries such as Hungary, Poland and Turkey which have signed up to the above-mentioned treaties and enjoy the membership/partnership of EU and NATO. Putting a distance from the values on which Europe and U.S. defined themselves through the hands of the strongmen is posing may be the greatest threat to the solidarity within and between both organisations.

To give only one more specific illustration of this scenario, the efforts to pursue an independent grand strategy, such as “America first”, may have the welcome effect on the decline of internationalism. The pattern of withdrawal of the US in taking the lead in building regional and global institutions or maintaining alliances is likely to leave a vacuum, which Russia and China will look to fill. On the other hand, Trump also declared that he wants peace through strength in his address to South Korea’s National Assembly in 2017. Contrary to his ambition, rather than strength based on shared values and interest, globally enjoyed unquestioned military dominance could easily become peace through war.[135] If the US changes its course, it will have implications on NATO and the EU’s role in the international security and stability. Especially in an environment in which the effects of nationalist, far-right, and populist parties within the Western civilization have started to become obvious. The impact of the codification of autocracy in Erdogan’s Turkey on NATO,[136] and the ‘Orbanisation’ of parts of the EU are other cases in point.

5. What can be done for the future?

Although the efforts to strengthen EU-NATO cooperation which have been initiated by the 2016 Joint Declaration are to be welcomed, the improvements have so far been made mostly on the bureaucratic than on the operational side. Further concrete steps are to be taken for a wider and substantial cooperation between two Brussels-based organisations who share 80% of overlap in membership and show a great level of interconnectedness in terms of security. Considering the new forms of warfare and challenges stemming from the Southern and Eastern flanks of Europe, we argue that a joint response must be formulated in the form of a common strategy, implemented in an integrated way by using a more comprehensive toolbox. In this regard, NATO’s 2018 Summit Declaration highlights that “defence capabilities developed by NATO and the EU shall be complementary, interoperable and available to both organizations”, with full “respect for the EU and NATO’s different mandates”. The Joint Declaration on EU-NATO Cooperation of that same year flags up the requirement of “political agreement” on the EU’s next budgetary cycle to give greater priority to security and defence. The Joint Declaration identifies counter-terrorism and resilience to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear-related risks as areas for future cooperation and singles out military mobility as a major priority for EU-NATO cooperation because it constitutes a prerequisite to both organisations’ readiness and responsiveness.

In order to widen the ‘essential’ EU-NATO cooperation and enhance the interconnected security environment for the two organisations, one might consider the following policy-agenda. Those are to be taken into account by either NATO, EU or both jointly.

- For deterrence and enhanced responsiveness against common challenges, the EU and NATO must adopt a proactive and integrated strategy and joint framework that encompasses all elements of soft and hard power and synchronises the interagency community to employ their sources to wage and counter external aggressions. (JOINT)

- Given the different nature of threats, capabilities and strategic interests of NATO and EU, one of the organisations should have a leading role in determining a joint strategy against one of the challenges emanating from East and South. While NATO can better react against Eastern challenges with its collective defence capability, EU can better cope with Southern challenges with its different wide-ranging tools. (JOINT)

- The joint strategy should include effective measures against rising illiberal and undemocratic tendencies within the member states. (JOINT)

- It is extremely important to go beyond bureaucratic issues and add formal substance to the cooperation in particular areas, such as assisting a rapid-reaction force deployment and a fast military build-up; combating organised crimes such as drug trafficking and people smuggling; intelligence fusion, crisis response; operation management; and smart burden sharing. (JOINT)

- The EU and NATO should combine their efforts for capacity-building in partner countries including security sector reform, defence institution building, and allocation of resources. (JOINT)

- The EU should be included as an organisation in NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP) would facilitate EU-NATO cooperation on defence capability building, however this would necessitate the non-NATO EU members to bear increased burden. For reciprocity, PESCO should be open to all NATO member country industries. (JOINT)

- The EU (and to some extent NATO) must reduce the dependency of the US protection and power projection; in this respect, it is important to exploit the current trend of increasing defence spendings. (JOINT)

- EU-Turkey relations, which can be seen as the main bottleneck due to the Cyprus issue, should be reformulated in such a way that it constitutes no longer an obstacle to the EU-NATO cooperation. (EU)

- Consensus-based NATO decision-making mechanism might be improved in a way that it furthers Alliance’s common interests. (NATO)

• Senior Research Fellow and Head of EU Foreign Policy Unit, Centre for European Policy Studies and Professor of EU External Relations Law and Governance, University of Amsterdam

•• Senior Research Fellow, Beyond the Horizon International Strategic Studies Group and PhD Candidate, University of Antwerp

••• Senior Research Fellow, Beyond the Horizon International Strategic Studies Group

•••• Research Fellow, Beyond the Horizon International Strategic Studies Group

- See, e.g., S. Duke, ‘The Future of EU-NATO Relations: A Case of Mutual Irrelevance Through Competition?’, 30 Journal of European Integration (2008), No. 1, 27-43; and J. Smith, ‘EU-NATO Cooperation: A Case of Institutional Fatigue?’, 20 European Security (2011), No. 2, 243–264. ↑

- Joint Declaration on EU-NATO Cooperation. (2018, July 10). Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156626.htm ↑

- See S. Blockmans & W. Van Eekelen, ‘European Crisis Management avant la lettre’, in S. Blockmans (ed.), The European Union and Crisis Management: Policy and Legal Aspects (The Hague: Asser Press 2008), 21–36. ↑

- See S. Blockmans, ‘Participation of Turkey in the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy: Kingmaker or Trojan Horse?’, KU Leuven GGS Working Paper No. 41 (2010). ↑

- Final Communiqué of the Ministerial Meeting of the North Atlantic Council, Press Communiqué M- NAC-1(96)63, 3 June 1996, para. 7. ↑

- Washington Summit Communiqué issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C. on 24 April 1999, Press Release NAC-S(99)64, 24 April 1999, para. 9. ↑

- NATO, ‘The Alliance’s Strategic Concept’, Doc. 0773-99 (Brussels, NATO Office of Information and Press 1999), para. 30. ↑

- The finalisation of the ‘Berlin plus’ arrangements was concluded with the signing of a Security of Information Agreement between the European Union and NATO on 14 March 2003. See Council Decision 2003/211/CFSP of 24 February 2003 concerning the conclusion of the Agreement between the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation on the Security of Information, Official Journal of the EU 2003 L 80/35. The agreement itself is not publicly accessible. For background and analysis, see M. Reichard, ‘Some Legal Issues Concerning the EU-NATO Berlin plus Agreement’, 73 Nordic JIL (2004), 37-67. ↑

- Joint declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission, and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’, 2016. ↑

- Statement on the implementation of the Joint Declaration signed by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission, and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’, 2016. ↑

- Progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorsed by NATO and EU Councils on 6 December 2016’, 2017. ↑

- Council conclusions on the Implementation of the Joint Declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. (2017, December 5). European Council. Retrieved from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/12/05/defence-cooperation-council-adopts-conclusions-on-eu-nato-cooperation-endorsing-common-set-of-new-proposals-for-further-joint-work/ ↑