Introduction

The U.S. President George Bush’s speech at National Defense University in 2005 caused a debate circulating for some time to gain more currency. He said: “It should be clear the best antidote to radicalism and terror is the tolerance kindled in free societies.” (VandeHei, 2005) This was an effort to justify the invasion of Iraq and to package it as a holy effort to bring democracy to the country in the absence of alleged WMDs and links to Al-Qaeda. He, in fact, redefined terrorism as a function of democracy.

Global Terrorism Database (GTD) defines terrorism as “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by non-state actors to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” (LaFree, Dugan, & Miller, 2015, p. 17) Crenshaw notes the watermark distinguishing ordinary organized crime and terrorism is the latter’s political motivation. (Crenshaw & LaFree, 2017) In other words, terrorism is a method used by political actors unwilling/unable to attain their goals under peaceful conditions. Since then we have been observing scholars making effort to understand the true nature of relationship between the two concepts, namely terrorism and democracy.

On the one side of the debate, there are proponents claiming democracy obviates terror. They argue democracy provides fertile grounds for peaceful solution of differences and probable conflicts. It allows free articulation of grievances and participation of individuals or groups to participate in the political processes to bring about proposed change within legal settings. They depart from the point that if a peaceful solution is possible, there would be no revert to costly violent tactics. Thus, they posit that terrorism is unlikely to flourish in democracies. This position is also a prescription for policymakers to cure terrorism and violent extremism. (Schmid, 1992; Eyerman, 1998; Li, 2005; Abrahms, 2007; Ash, 2014)

On the other side, opponents argue that the wide range of freedoms and permissiveness associated with democracy offer ample opportunities for terrorist groups to form and actively pursue political agenda. The inability to take harsh measures and low threshold to stand human loss based on electoral and social calculations make democracies even greater target for terrorism. (Eubank & Weinberg, 2001; Chenoweth, 2013) Despite reaching the same conclusion, Chewoneth attributes motivation for terrorist attacks in democracies to intergroup dynamics, finding meaningful correlation between number of political competitors and occurrence of terror events (2010).

A third group of scholars can be cited as those not finding a meaningful relationship between democracy and occurrence of terrorism but associate the core reason to other factors. Piazza, dismissing direct link between terrorism and democracy, attributes the reason for the former to state failure. (Piazza, 2007) Findley and Young attribute it to the regime’s potential to abuse power. They opine that an independent judiciary restrains governments, and make their commitments more credible irrespective of regime type. This further provides less incentive for terrorism. (2011)

The problematic and even perplexing dimension of the issue is that all three camps support their theories with statistical data, based on their selection of the dataset. By penning this article, our intention is not to take a side in this debate but to test the link between regime type and terrorism with a different way. All studies hereto address the debate from the source side, meaning the chance of occurrence of terrorist events in states. Therefore, the unit of analysis in these studies is country-year. We, however, structure our dataset in a way that take terror groups as unit of analysis with a temporal variation, and test the impact of regime type on terrorist group termination. In doing that, we focus on the effect of different types of regimes, such as democracy, autocracy and anocracy. Furthermore, we also perform our statistical analyses not only with a way that tests the effect of certain regimes on terrorist group termination, but we also test the impact of the degree of said regime types on terrorist group failure. More specifically, we look at what effects the degree of democracy, anocracy and autocracy have on terrorist group survival. In the next section, we outline the data sources, measurements and methodology that are used to assess the link between regime type and terrorist group termination.

Research Design

In creating the sample of terrorist groups, we use Young and Dugan’s (2014) dataset on terrorist groups that they have constructed based on the terrorist attacks covered in Global Terrorism Database (GTD) (LaFree & Dugan 2007). According to Young and Dugan’s (2014) rules of identifying terror groups, the terror groups in the data are defined as terrorist groups as long as they use terrorist tactics. There are 2,223 terror groups that engaged in terrorist violence between 1970 and 2010. Our unit of analysis is terrorist group-year. Young and Dugan (2014) assigns each terror group to a country, which is named as “primary country”, in which the terror group mostly carries out its terror attacks during its existence.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is “terrorist group termination”. We measure our dependent variable with Young and Dugan’s (2014) data, and consistent with their dataset, a terrorist group has been coded as “terminated” if it ceases to exist or it stopped using terrorist tactics. If the group has been terminated, it has been coded 1, and it is coded 0 for the otherwise. Once the group has been coded 1, it exits the data. In analyzing the data, we use discrete time survival model as the estimation technique due to our data structure.

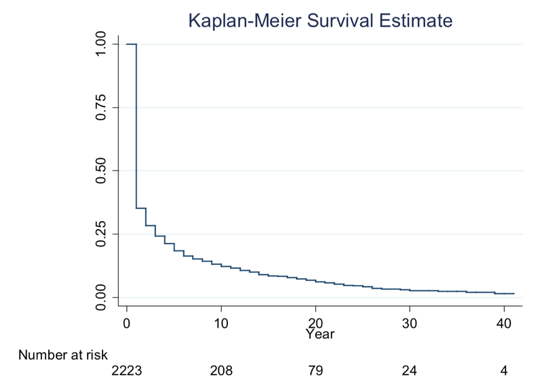

In terms of the survival patterns of terrorist groups in the data, the average survival rate for the terrorist groups is 3.33 years, and almost 68% percent of the groups stopped operating within their first year. About 20 percent of all groups managed to survive five years after they started operating (Young and Dugan 2014, 7-8). Figure 1 below is Kaplan-Meier survival estimate for 2223 terror groups in Young and Dugan’s (2014) data. In the figure, Y axis represents the risk of failure, and X axis represents the years terror groups survive. The figure has been borrowed from Young and Dugan’s (2014) article.

Figure 1 The Survival Estimates of Terrorist Group Termination for 2223 Terrorist Organizations, 1970-2010

Independent variable

The independent variable is regime type. We measure regime type with Polity IV dataset (Marshall, Gurr & Jaggers 2015). The dataset gives us a scale ranging from 10 to -10, and 10 represents the most democratic edge of the scale whereas -10 represents the most autocratic edge. As the scores in the scale increase, the level of democracy increases. We also create dummy variables for democratic, autocratic and anocratic regimes. The states scoring 6 or higher in the dataset are coded democracy. Those scoring between 5 and -5 are coded anocracy. Finally, states scoring -6 or lower are coded autocracies. In addition to creating dummy variables for certain regime types, we have also assigned dummies to measure the degree of these regime types. We code states scoring 9 or 10 as strong democracies, 6, 7 or 8 as weak democracies. Likewise, states scoring -9 or -10 are coded strong autocracies whereas those scoring -6, -7 or -8 are coded as weak autocracies. For anocratic regimes, we code states scoring 0 to 5 as open anocracies, and those scoring -1 to -5 as closed anocracies.

There is no consensus on definition of anocracy. These regimes are incoherent in a way that intermingle democratic and autocratic regimes. They allow opposition groups to participate in politics at some extent but they lack or have incomplete mechanisms to redress grievances (Regan & Bell 2010; Gandhi & Vreeland 2008; Fearon & Laitin 2003;Benson & Kugler 1998). In closed anocracies, political challengers emerge from within élites whereas those may come from all segments of society. (Cole & Marshall 2014).

Control variables

We control for some factors that might potentially blur the relationship between regime type and terrorist group termination. To start with, existence of an ongoing civil war is controlled due to the reason that the phenomenon arises commonly within civil war context (Findley & Young 2012) and the same context has potential to enhance durability of terror groups. To that end, UCDP Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al. 2002) is used to denote existence of civil war in a given year. A dichotomous civil war variable is coded, 1 to indicate existence and 0 otherwise. Some terrorist group characteristics are also controlled because these characteristics play a significant role on the survival of such groups. Group size is controlled because it might be harder to defeat larger terror groups as they recruit more people and increase their capacity in size. We control for group ideology, and terror groups adopting a nationalist ideology because these groups are relatively more durable than other terror groups, such as LTTE, IRA, PKK, ETA. We code nationalist/ethnic terror groups 1, and those not ethnic/nationalist agenda 0. We measure group size and group ideology variables by using Jones and Libicki’s (2008) data. Jones and Libicki’s (2008) data include 648 terror groups in their sample, and provide some variables capturing group characteristics, such as group size, ideology, the breadth of group goal(s). We also control for attack diversity of the terror groups since more diverse types of attacks enhance the terrorist group survival (Blomberg, Gaibulloev & Sandler 2011). Global Terrorism Database distinguishes those in eight categories (e.g., assassinations, armed assaults, and bombings). The variable ranges between 0 and 1, with larger numbers corresponding to greater diversity. If the terror group uses bombings during its lifespan, its diversity is 0. Operating in multiple countries (foreign presence) is also controlled because when the terror group has foreign presence, they may find more resources for survival. In addition to group characteristics, we control for a systemic factor, the Cold War. Post-cold war is coded due to the reason that terrorism becomes increasingly a transnational security challenge in this period. Finally, GDP per capita and population are controlled. This has been done to remain consistent with literature on terrorism as these two factors have been usually controlled in those.

Results

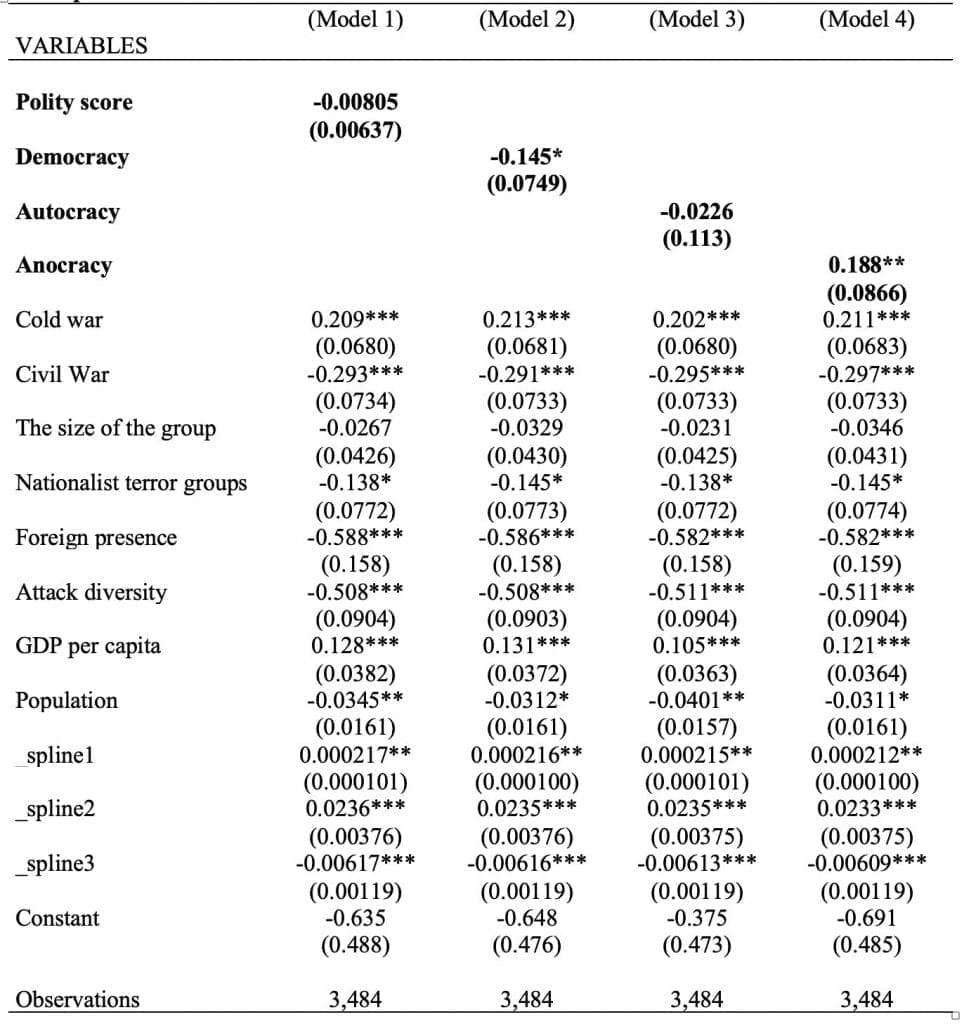

Table 1 presents the results of logit discrete time survival analysis. The analyses have been conducted with STATA 13. The robust standard errors, which are in parentheses below the coefficients, are reported and clustered on terror groups. In interpreting the empirical results, we focus on the coefficients. The coefficients take positive or negative signs. The positive coefficients suggest that a given variable increases the likelihood of terrorist group termination, and the negative coefficients decreases. The coefficients with stars indicate that they are statistically significant, suggesting that the variable has a significant impact on terrorist group termination. One star represents the statistical significance at 90 percent confidence level. Two stars represent the statistical significance 95 percent, and three stars represent 99 percent confidence interval. There are four models in the table. The first model presents the finding on polity score, and the rest of the models has the findings on three regime type dummy variables. The control variables are included in all models.

According to the first model, polity score variable’s coefficient is not statistically significant, suggesting that the changes in the scale of polity score variable do not have a significant impact on terrorist group termination. In terms of the results on the regime type dummy variables, the democracy variable in the second model is statistically significant at 90 percent confidence level and has a negative sign, which indicates that being a democratic regime significantly reduces the likelihood of terrorist group termination. For the autocracy variable, however, it does not achieve a statistical significance, and this suggests that being an autocratic regime does not have a significant effect on terrorist group termination. Finally, the coefficient for the anocracy variable is statistically significant at 95 percent confidence level, and it has a positive sign, suggesting that being anocracy increases the likelihood of terrorist group termination. This finding is interesting in the sense that the extant literature converges on the idea that anocracies experience more instability and political violence than democracies and autocracies. Our finding on the effect of being anocracy on terrorist group termination shows that they are actually more successful in eliminating terror groups than democracies and autocracies.

Table 1 Logit Discrete Time Survival Results on The Effect of Regime Type on Terrorist Group Termination

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

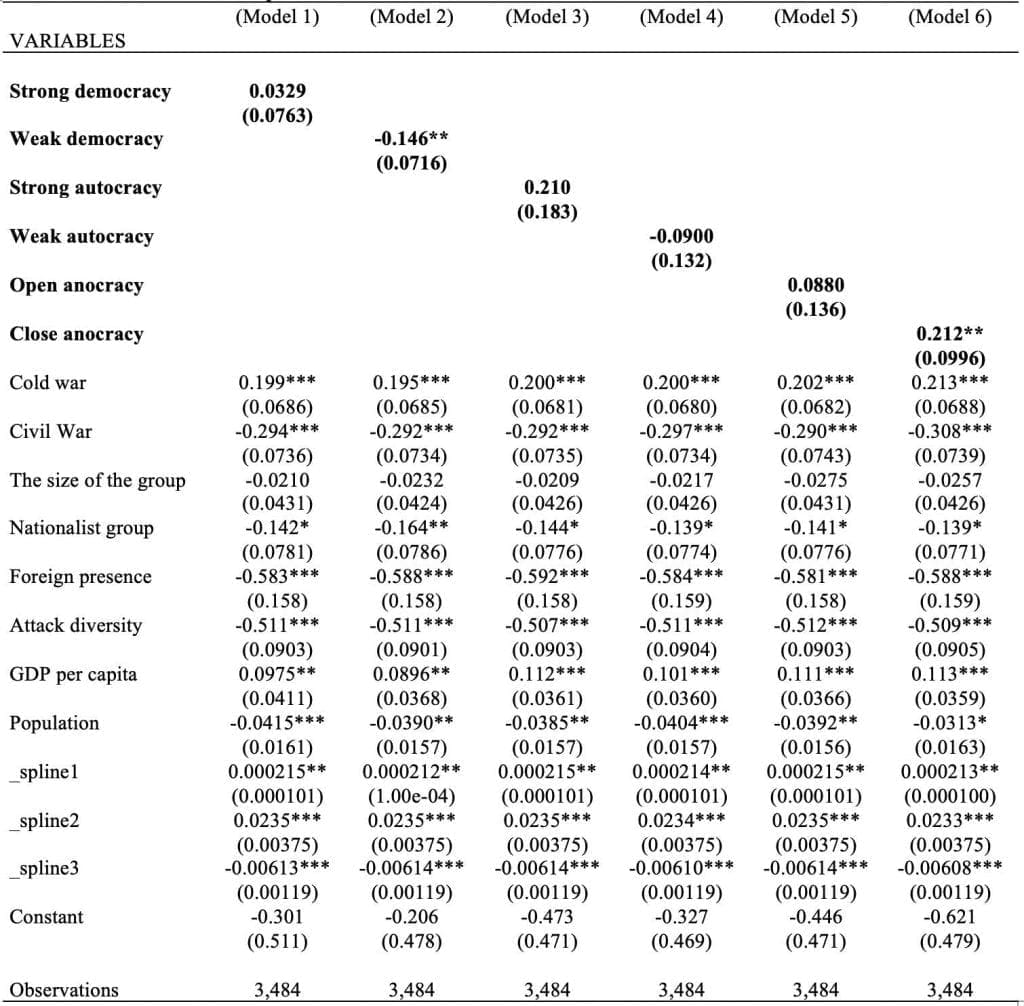

In terms of the effect of the degree of these regime types on terrorist group termination, the results on Table 2 suggest that while the role of being a strong democracy is not significant, terror groups are less likely to fail in weak democracies. For the strong and weak autocracy variables, they both don’t have a statistically significant impact on terrorist group termination. The results on open and closed anocracies report no significant connection between being an open anocracy and terrorist group termination. But they also report that being a closed anocracy significantly increases the likelihood of terrorist group termination.

The findings on the control variables in both tables suggest that terror groups are more likely to end in the post-cold war era. The coefficients of the civil war variable suggest that terror groups operating in a civil war context are less likely to terminate than those operating in non-civil war context. The size of the terror group, unexpectedly, does not have a significant impact on the terrorist group termination, which is not consistent with the conventional wisdom that the larger terror groups are the more likely will they survive longer. The other variables that might capture the strength of the terror group, namely, attack diversity and operating in multiple countries significantly affect terrorist termination. More specifically, terror groups operating in multiple countries and have diverse attack strategies are less likely to fail than those not operating in multiple countries and not adopting diverse attack strategies. In terms of the effect of the ideology of the terror group, the coefficients of the nationalist terror group dummy variable show that ethnic terror groups are less likely to survive longer than non-ethnic terror groups. Finally, the results on GDP per capita and population suggest that terror groups are more likely to end as the target state has higher economic development, and they are less likely to fail as the population size of target state gets greater. After reporting the findings, we now turn to discuss these findings in the last section of the paper.

Table 2 Logit Discrete Time Survival Results on the Effect of Disaggregated Regime Types on Terrorist Group Termination

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Conclusion

In this paper, we have revisited the debate addressing link between regime type and terrorism. In the extant literature, the studies predominantly test the effect of regime type on number of terrorist incidents experienced. Central to this paper’s goal is to build the literature in a way that conduct the same statistical tests for terrorist group termination in order to show how the different regimes perform in fighting terror when they experience it. The results of our empirical analysis demonstrate that terror groups are less likely to fail in weak democracies. They also suggest that there is no significant relationship between being an autocratic regime and terrorist group termination regardless the strength of the autocratic regime. Our findings with respect to the effect of being an anocratic regime on terrorist group end demonstrate that closed anocracies, which include more authoritarian characteristics than open anocracies seem to be more successful than other regimes in eliminating terror group. This finding is interesting in the sense that the extant literature has demonstrated that anocracies are more vulnerable to experience terrorism (Piazza 2008; Abadie 2004). In other words, anocracies seem to experience more terrorist violence but when they experience terrorism, they seem to be more likely to achieve success in eliminating terrorist groups. Since the goal of our paper is to revisit the debate focusing on the link between regime type and terrorism in a way that only test the effect of the different regimes on countering terrorism, we don’t have a strong theory that can explain why anocracies are more prone to terror, but they are more successful in eliminating it. Future studies addressing this debate should focus more on the counterterrorism capability of different regime types, particularly anocratic regimes. Likewise, the finding that terror groups are less likely to be terminated in weak democracies also need plausible theoretical explanations. While the literature includes studies looking at the effect that the degree of democracy has on experiencing terrorism (Findley & Young 2011), more research seems to be needed that should address the role of the degree of democracy on eliminating terrorism. As a concluding remark, the debate on the regime type and its link to terrorist violence is primarily studied to show which regimes are more prone to terror in the first place. This debate, however, should also be studied further in the sense of exploring the varying degree in the counterterrorism capacity of the different regimes in order to help us better understand the variation among these different regimes in countering terrorism.

* Michael Sanchez is non-resident Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon.

** Onur Sultan is a senior research fellow at Beyond the Horizon ISSG and a PhD candidate at the University of Antwerp.

Bibliography

Abadie, A. (2006). Poverty, political freedom, and the roots of terrorism. American Economic Review, 96(2), 50-56.

Abrahms, M. (2007, April – June). Why Democracies Make Superior Counterterrorists. Security Studies, 16(2), 223-253.

Ash, K. (2014). Representative Democracy and Fighting Domestic Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1-21.

Benson, Michelle; Kugler, Jackek (1998). “Power Parity, Democracy, and Severity of Internal

Violence”. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 42 (2): 196–209.

Blomberg, S. B., Gaibulloev, K., & Sandler, T. (2011). Terrorist group survival: ideology, tactics, and base of operations. Public Choice, 149(3-4), 441.

Chenoweth, E. (2010, January). Democratic Competition and Terrorist Activity. The Journal of Politics, 72(1), 16-30.

Chenoweth, E. (2013). Terrorism and Democracy. The Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 355-378.

Cole, B. R., & Marshall, M. G. (2014). Global report 2014 conflict, governance, and state fragility. Center for Systematic Peace.

Crenshaw, M., & LaFree, G. (2017). Countering Terrorism. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Eubank, W., & Weinberg, L. (2001). Terrorism and Democracy: Perpetrators and Victims. Terrorism and Political Violence, 13(1), 155-164.

Eyerman, J. (1998). Terrorism and Democratic States: Soft Targets or Accessible Systems. International Interactions, 24(2), 151-170.

Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American political science review, 97(1), 75-90.

Findley, M., & Young, J. (2011). Terrorism, Democracy, and Credible Commitments. International Studies Quarterly, 55, 357–378.

Findley, M. G., & Young, J. K. (2012). Terrorism and civil war: A spatial and temporal approach to a conceptual problem. Perspectives on Politics, 10(2), 285-305.

Gandhi, Jennifer; Vreeland, James (2008). “Political Institutions and Civil War: Unpacking Anocracy”. Journal of Conflict Solutions. 52 (3): 401–425.

Gleditsch, N. P., Wallensteen, P., Eriksson, M., Sollenberg, M., & Strand, H. (2002). Armed conflict 1946-2001: A new dataset. Journal of eace research, 39(5), 615-637.

Jones, S. G., & Libicki, M. C. (2008). How terrorist groups end: Lessons for countering al Qa’ida. Rand Corporation.

LaFree, G., & Dugan, L. (2007). Introducing the global terrorism database. Terrorism and Political Violence, 19(2), 181-204.

LaFree, G., Dugan, L., & Miller, E. (2015). Putting Terrorism in Context: Lessons from the Global Terrorism Database. Routledge.

Li, Q. (2005). Does Democracy Promote or Reduce Transnational Terrorist Incidents? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(2), 278-297.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2015). Polity IV Project: Regime characteristics and transitions, 1800-2015. Dataset users’ manual.

Piazza, J. A. (2007). Do Democracy and Free Markets Protect Us From Terrorism? International Politics, 45, 72-91.

Piazza, J. A. (2008). Incubators of terror: Do failed and failing states promote transnational terrorism?. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 469-488.

Regan, Patrick; Bell, Sam (2010). “Changing Lanes or Stuck in the Middle: Why Are Anocracies More Prone to Civil Wars?”. Political Science Quarterly. 63 (4): 747–759

Schmid, A. (1992). Terrrorism and Democracy. Terrorism and Political Violence, 4(4), 14-25.

VandeHei, J. (2005). Bush Calls Democracy Terror’s Antidote. The Washington Post.

Walter, B. F. (2017). The New New Civil Wars. The Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 469–486.

Young, J. K., & Dugan, L. (2014). Survival of the fittest: Why terrorist groups endure. Perspectives on Terrorism, 8(2).

Contact

Phone

Tel: +32 (0) 2 801 13 57-58

Address

Beyond the Horizon ISSG

Davincilaan 1, 1932 Brussels