Abstract

Today radicalization and extremism are the two salient issues facing the policymakers in most of the countries. However, it is difficult to say that there is a consensus on the definition of radicalization. The lack of a common definition creates big challenges to define the radicals’ features. Furthermore, the countries’ security-based policies against the radicalization force the radicals to stay hidden in the society. Then it makes the situation worse to reach and recruit the radicals for the research projects about radicalization and extremism. In this regard, this article will introduce how we can recruit the radicals who are staying as a “hidden population” in society.

Introduction

“Radical” and “radicalization” are two highly common terms that one encounters in daily social gatherings or texts. Radical view, radical development, radical effect, radical feminist, radical solution and radical steps can be cited as several examples to those. Although the extent unclear, the user by using this term tries to emphasize a big or extreme change from the original condition. However, based on this ambiguity, it is not certain if this change will evolve into a dangerous situation or more precisely to a threat towards society.

After 9/11, 2004 Madrid bombing and 2005 London terror attacks, the term has taken a different turn by acquiring different connotations mostly rooted in emerging security based definitions. In the whirlwind of multiplicity of definitions, the academics and the policy makers still grapple to find out an explanation, which will capture the true nature of the phenomenon and help formulating policies to treat the problem and those affected from it. However, it is difficult to say a consensus has come to emerge on one definition. On the contrary, it has turned into a more complicated and highly political term.

In the current situation, although almost all countries see radicalization as a societal challenge, the ambiguity on the term still persists. It is still unclear whether it is a process spiraling down to violence or a sudden emotional explosion. Peter Neumann explain radicalization as “What goes on before the bomb goes off (Neumann, 2008, p. 4). He thinks that it is a pathway to the violence. However, Randy Borum thinks that “Ideology and action are sometimes connected, but not always” (Borum, 2011). Here we see that it is not always possible to set a link between radical thoughts and violent actions. There are radicals who have never been involved in or have been support of any sort to any violent action. Furthermore, it is difficult to say that all terrorists have a radical ideological background (Borum, 2011).

All these different approaches and explanations are very important to understand the radicalization issue and the radicals. However, it is clear that without having a common definition and common understanding about radicalization it will be really difficult to build a counter strategy or a program aiming to prevent it.

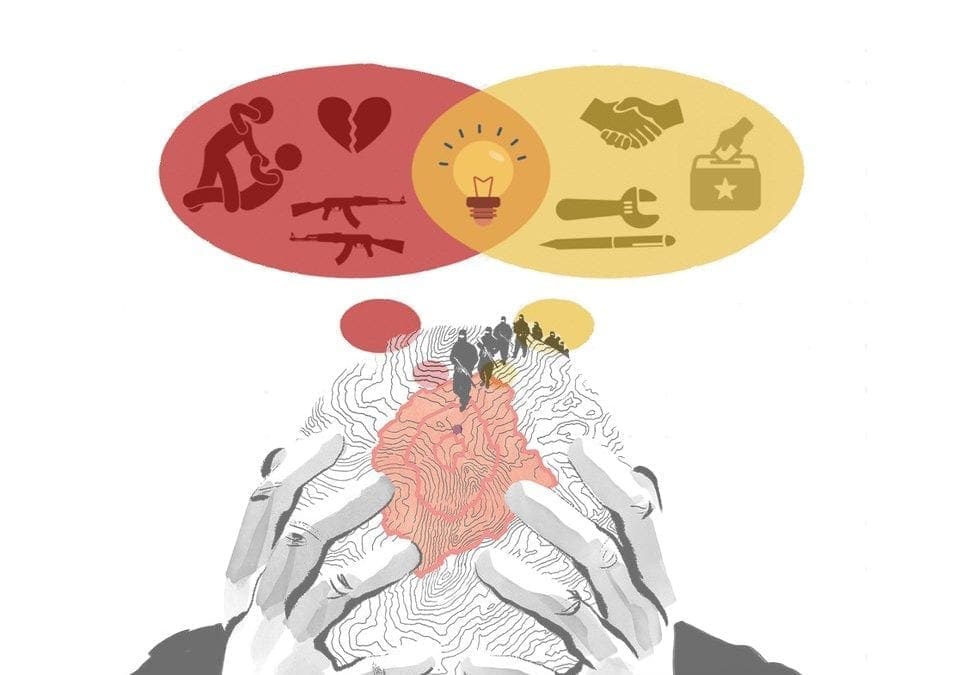

Another important aspect of the issue is that the definition also determine the approaches and the methodologies for such counter-radicalization programs. Linking radicalization directly to violence will lead policymakers to security-based approaches and methodologies, while programs based on an understanding of radicalization as a political position normally will lead to discourse-based approaches.

In more practical terms, ill-defined explanation of radicalization creates big challenges to reach the radicals who are hidden in the society. It would be naïve to expect to reach out to real radicals without understanding the terminology. On the other hand, without reaching the radicals and consulting their knowledge about their experiences into radicalization, it will be difficult to find a suitable or more understandable explanation about radicalization. Hence, we need to make the situation more clear, and it would be better to start with finding and recruiting the person who is known or who describes themselves as radical in the society.

Who are Hidden, Hard-to-Reach and Vulnerable Populations?

The groups, which are excluded from society, and difficult to be reached by the researchers, get different names such as hidden societies, hard-to-reach societies or vulnerable societies. These groups’ social and physical locations as well as hidden and vulnerable natures have effect in getting these names. In this regard, living in a very difficult geography and lack of easy transportation can be a reason to be call a group “hard to reach population”. In fact, those groups are not in a hidden position, but they are not accessible either. For example, the indigenous ethnic group, who are called Yashkun, Shin and Kameen, lives in the Hindu Kush Mountains (Aase, 2014). The group has a population of some 20.000 people. It is clear that they are not hiding themselves from the others. However, the place where they live is nearly inaccessible to the others.

From social accessibility perspective, abused women, gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender can be cited as other examples of hard to reach populations. It is possible to increase number of these examples by including illicit drug users, gang members, the HIV-positives, immigrants, ethnic minorities and so on (Acharya, 2007; Heckathorn, 1997; Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

All these groups can be called hard to reach, vulnerable or hidden population. However, giving different names sometimes increase the complexity of the situation. One group can be hard to reach population, but at the same time, they can be vulnerable as well. For example, abused women live in the society and continue their lives, but when the subject becomes sex violence, they tend to keep silent and behave as hard to reach population because they are highly vulnerable. Hence, most of the academics use the term “hidden society” to describe this kind of populations.

The hidden population is defined as a subset of the general population whose membership is not readily distinguished or enumerated based on existing knowledge and sampling capabilities (Lambert, 1990). This is a very common explanation to describe the hidden societies. As we understand from the definition, the traditional sampling methods do not suit the hidden societies because these marginal groups do not have high visibility in the society (Valdez & Kaplan, 1998).

Why Is It Difficult to Reach Hidden Populations?

There are many different hidden populations in society, and all of them have nearly the same characteristics.

Strong privacy concern is one of the reasons behind their secrecy (Heckathorn, 1997). For example, the women who have trouble with sexual assaults do not voluntarily participate to the research because they do not want to be seen as a symbol of sexual victimization or labelled as a raped woman (Harned, 2004). Similar hesitations exist in other hidden societies such as bisexual, gay, lesbian or transgender population. They see in high risk in revealing their sexual identity when they participate in research. The risk here is to be faced with discrimination, stigmatization, harassment or violence in the society (Herek, 2009). Illicit drug users can be cited as another hidden group who are also reluctant to be respondent. Their main motive is not to have trouble with police and legal system (Faugier & Sargeant, 1997). Immigrants and ethnic minorities can be called as hidden societies as well. Although they are visible in the society, they sometimes do not want to be the part of research projects because they do not expect any benefit from the results of the projects (Corbie-Smith, Moody-Ayers, & Thrasher, 2004). Furthermore, they do not trust the person who does not speak their own language (Shedlin, Decena, Mangadu, & Martinez, 2011).

Radicals in the Society

The profiles or behaviours of radicals in the society match to those of hidden populations. Because their reflections in the society are very similar to the other hidden populations. Moreover, it is possible to say that they hide better than the others do because the nature of radicalization or being radical is directly related with the secrecy. Maybe it was not like that before 2000s, but after the 9/11 and the following bomb attacks in Europe, the situation has completely changed.

The newly coined term “homegrown terrorism” has repercussions going deep if scratched in the surface. The term implies that the danger is not coming from outside but it has festered within the body, evoking the feeling of treason. The persons who grow up in the same country become a threat because of their radical worldviews. A secondary implication is that such individuals have no integration problems with the society or at the very least the others such as friends or family members around them cannot catch any big change in their attitudes. Some of them have very good education and social environment, but at the end, this group conducts highly detrimental violent actions in the society.

Getting back to Neumann’s definition, when the bomb goes off, we call them terrorists. But the big controversy is about what we can call them before that. Of course, if a person becomes a member of a terrorist organization and has a gun, then it is clear that this person is terrorist, but how can we name the others who neither have any relationship with any terrorist organization nor do they support any violent actions even they have radical thoughts? For example, many salafists do not support ISIS or Al Qaeda. This becomes a never-ending discussion among academicians and policymakers.

Most of the countries prepare their counter-radicalization programs based on the idea that radicalization is a process or a pathway to the extremism or violence. This approach does not see the radicals as terrorists, but also does not treat them as normal citizens.

Anders Behring Breivik[1] and Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel[2] cases are the two examples which reinforce the security-based approaches to the radicalization and radicals. Two factors in Breivik and Bouhleh cases make the situation more complicated. We know that being in a like-minded group facilitates the ideological development of the individuals. However, both Breivik and Bouhleh were alone in the process, and they managed to radicalize themselves without connection with any other radical or terrorist organizations. Second, although they have completely different ideologies, their actions were very similar to each other, which means that all the radicals are dangerous no matter how different ideological backgrounds they have.

As a result, it is possible to say that the negative connotations of the term “radicals” mostly associated with terrorism, violence and murder create pressure on radicals to stay in hidden in society with this ideological orientation. Their motives are to evade being excluded, alienated or demonized in society.

Recruiting Strategies for Radicals

As we understand from Lambert’s definition, the traditional sampling methods do not suit to the hidden societies because these marginal groups do not have high visibility in the society (Valdez & Kaplan, 1998). Moreover, the standard sampling methods require finding sample members with a known probability of selection which means that the researcher must have sample frame, a list of members in that population (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). It can be said that this is not applicable to hidden societies especially to those belonging to radical organizations because there is no existing list like that. The inadequacy of the traditional methods drives the researchers to find out new technics to reach the hidden societies. As a result of this attempts, a number of different methods such as snowball sampling, respondent driven sampling, targeted sampling, time location samplings, capture-recapture technic, multiplier method and fieldwork sampling have been developed. All these technics were used to reach a different kind of hidden population. However, all of them has some inherent challenges because of common features of hidden populations. For example, the mobile situation of the hidden groups creates big challenges to reach them through the community institutions such as police office or health care system (Faugier & Sargeant, 1997). Generally, the number of hidden groups are not so many (Goel & Salganik, 2009), which creates other challenges in terms of finding a significantly large and representative sample for the target hidden group (Medhi, Mahanta, Akoijam Brogen, & Adhikary, 2012).

Targeted Sampling;

The targeted sampling method is used to find the members of hidden groups according to the public places where they are mostly seen. This technic is sometimes called “street outreach” as well (Watters & Biernacki, 1989). The researcher prepares a geographical map then send the fieldworkers to the selected places in order to recruit a person from the hidden society (Acharya, 2007). Patrick Biernacki and John Watters use the technic to reach the drug users who have the risk to have HIV infection and AIDS (Watters & Biernacki, 1989). This technic is very beneficial to recruit the person who is not registered to any communal institutions. However, it is difficult to say that the result of the recruitment can reflect the hidden population. This means that the results cannot be generalized.

Furthermore, it is a kind of labour intensive technic because it requires too many fieldworkers and too much time to reach the expected outcome. When it comes to the radicals, this technic can be insufficient to find them because most of the radicals do not visit the same public places. Sometimes it is possible to find the religious radicals in religious institutions or mosques, but they also exist in mundane places such as cafes, gym clubs (RAGAZZI, 2014). It means that before conducting this method, a very detailed ethnographic study is required about the targeted radical society. However, even after this detailed study, it is not guaranteed that the radicals will be reached with targeted sampling methodology.

Time Location Samplings (TLS);

It is possible to say that time location sampling is an alternative method to targeted sampling method. The main principle in TLS is to specify a map of places and venues (as in Targeted Sampling method) where the radicals mostly visit or use for their gatherings. Then the time and period are prepared for visiting the specified places. After finishing this process, the researcher visits the places according to the planned time in a day to find and recruit the members of the hidden group (Mackellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996). Researchers, who studied on how truck drivers help to disseminate the HIV in Brazil, used this method with success (Ferreira, Oliveira, Raymond, Chen, & McFarland, 2008). They identified five venues at four truck stops. Then they began to observe the places during the daytime and in the night. After this process, they identified four hour time periods in a day for the different venues, and these findings were constructed general as venue day time (VDT) periods for truck drivers.

In this project, it is seen that the researchers did not have so much trouble to find out the specific places where the truck drivers usually congregate. However, when there are not a specific place for å focus, then this creates big challenge. Moreover, when the hidden groups do not prefer to meet in a public place, it is a big problem for the researcher because private venues are not accessible for the researcher (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

Another problematic issue is the generalization of the information. It is difficult to assume that the recruited persons according to the VDT can reflect all the hidden populations (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). For example, it is possible to find the drug users in one place, but it can be problematic to allege that the data that comes from these drug users can be generalized for all the drug users. The same challenges exist for the radicals as well. Furthermore, the radicals do not tend to meet in one place especially in public place. Therefore, we can say that the troubles in the targeted sampling method show itself in this method again.

Capture-Recapture, Field Work and Multiplier Method Technic;

The capture-recapture method is initially conducted to count the number of wild animals in nature (Shaghaghi, Bhopal, & Sheikh, 2011). Afterwards, it is used to find the hidden population in society. The main goal of the method is to estimate the size of the hidden group. The success of the technic rely on the prepared lists which are independent of each other; then these lists are compared by the researchers with some statistical models (Williams & Cheal, 2002). According to the number of overlaps, the researchers get a conclusion about the number of members of the hidden population. William and Cheal used this technic to find out the homeless population in the UK. According to them, the researcher should avoid dependency while preparing the list, and the total number of the hidden population must stay stable throughout the research (Williams & Cheal, 2002). Hay and Gannon, other two researchers, used the capture recapture method to identify the number of drug users in Scotland. The researchers got the main data from the treatment centers, general practitioners (GPs), police, and social work institutions (Hay & Gannon, 2006).

The fieldwork is another version of the capture and recaptures technic (Richard, Brian, & Donald, 2011), which aims to find out the numbers of the hidden populations. The researcher reaches the data from the specified places such as streets, bars, dance clubs and so on instead of getting it from the institutions. For example, Richard Berk, Brian Kriegler and Donald Ylvisaker used the technic to count number of homeless people in Los Angeles County. After they specified the places where the homeless exist, they paired the enumerators with the homeless individuals who were hired as a guide to show the census tracks in the Los Angeles County.

Multiplier method is also a different version of capture-recapture technic, which is conducted to estimate the number of hidden population. Here, the researcher reaches the unknown population by using the known population (Hope, Hickman, & Tilling, 2005). It can be said that the method mixes the capture and recapture technic with the fieldwork technic. One of the sources is the institutions, which are well-known for everyone. The other data source is the hidden population itself. This technic serves well to test official lists’ accuracy as well.

It is seen that the capture and recapture method is very useful when there is a chance to reach the data through the public or private institutions. For example, while studying hidden criminal populations, it is easy to access the information about the numbers via police records. However, it cannot be possible to find any numbers related to the radicals from such institutions. There can be some information about the radicals within police records or social institutions, but these numbers reflect the radicals who have been involved in criminal events, and it is difficult to assume that this data can be used as basis for all radicals.

Another challenge is the stability of the radicals. It is nearly impossible to be sure about engagement and disengagement process with the radical groups. There is no quantifiable subscription or cancellation of membership to the radical organizations.

Furthermore being a radical or not is a cognitive status, very difficult to be observed and reported by outsiders. The fieldwork and multiplier technics involve similar challenges with capture and recapture technic for reaching the radicals. Firstly, it is not easy to hire a radical as a guide. Secondly, even if it becomes possible; there are not specific map of places where the radicals visit.

Snowball Sampling and Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS)

Snowball sampling is defined as a “technique for finding research subjects. One subject gives the researcher the name of another subject, who in turn provides the name of a third, and so” (Vogt, 2005). Snowball sampling is mostly used to conduct qualitative research on hidden populations. Furthermore, it helps enumerating the hidden population as well (Atkinson & Flint, 2001). Biernacki and Waldorf explain the method as; “The method yields a study sample through referrals made among people who share or know of others who possess some characteristics that are of research interest”(Watters & Biernacki, 1989).

It is seen from the explanation that the conceptual background of snowball sampling is based on the assumption that the members of hidden organizations have relationships with each other. The way of conducting it involves a couple of steps. First is obviously to reach initial hidden group members who are called “seed” (Atkinson & Flint, 2001). This group can be a subgroup of the hidden population and can be recruited through fieldwork. Then these members turn to the hidden population, find another and convince them to be part of the research project. This process continues until the researcher reach the targeted sampled size or the sample has become saturated (Magnani, Sabin, Saidel, & Heckathorn, 2005).

Respondent-driven sampling, on the other hand, is mainly used to estimate the proportion of the hidden population. Instead of getting this information directly from the sample (because it is nearly impossible in hidden populations), the RDS use an indirect method to reach that (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Therefore, it is very necessary to find out the social network in the hidden population, which help to estimate the population. The system starts with establishing a seed group. Each seed recruit at least one new person from his/her social network. During this recruitment process, seeds provide a coupon (money or gift) for each person that they recruited. This incentive system, which encourages the respondent to find a new participant for the research project (Goel & Salganik, 2009), deter some ethical challenges as well because the recruitment takes place through the participants instead of the researcher. The recruitment process continues until the researcher reaches the desired sample size (Acharya, 2007).

This link tracing design samplings (snowball sampling and RDS) are used to find many different hidden populations. For example, Petersen and Valdez used snowball sampling to reach the gang affiliated adolescent females (Petersen & Valdez, 2005), a group of researcher compared TLS, RDS and snowball sampling on the study of behavioural surveillance in men who have sex with men in Brazil (Kendall et al., 2008). Handcock and Gile used RDS to estimate the number of hidden populations who have the high risk for HIV (Handcock, Gile, & Mar, 2014), Heckathorn used the RDS to reach the illicit drug users (Heckathorn, 1997, 2002). Salganik and Heckathorn studied on jazz musicians in San Francisco by using the RDS (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

It is possible to increase the numbers with many other examples because it can be said that these technics suit to find and recruit many different hidden populations. It is very useful to conduct these technics when there are limited recorded information or data sources. Snowball sampling and RDS are cheaper, accurate and quicker when they are compared with the other technics (Acharya, 2007; Atkinson & Flint, 2001). Furthermore RDS technic achieves to recruit many respondents (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

However, these methods involve some drawbacks as well. The main challenge is that these technics requires many people researchers in the project. Attaining success in contacting the hidden group is another challenge (Faugier & Sargeant, 1997). The researcher must verify the eligibility of the newly recruited person. Sometimes that is possible to recruit a new person who is in fact not a member of a hidden population. Therefore the researcher must ensure the respondent connection with the hidden population (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

Conclusion

Although the radicals/extremists form a hidden society, they have connection with each other because nearly all theories about radicalization process pay attention to the group effect in the radicalization process. Finding a place in like-minded group facilitates the radicalization process (Moghaddam, 2005; Silber & Bhatt, 2007). Of course, there are exceptions such as Breivik and Bouhleh, but the general tendency of radicals is to move together with the other members of the radical organization. In this regard, link tracing design technics are suitable to reach the radicals.

The initial part, finding the seeds, have some challenges in terms of reaching the target group. Because there is low probability that a specific place and time exists to find them. However, social, religious institutions and former radicals can be a starting point for the researcher. By their guidance, it is possible to recruit a small group, which can be assumed as a seeds. Reaching radicals through internet can be another option because there are many blogs, social media accounts, and internet web pages related to radical organizations which can show the social network of radicals especially when they are online. The researcher can connect to this virtual environment, communicate with them and identify some suitable participants for his/her research. There are also some challenges in this process. The usernames of radicals can be different from the originals. Furthermore, one person may have more than one account, which creates a complex situation. Despite those difficulties it is a precious way to be explored.

All in all, despite difficulties to reach the radical population through snowball sampling and RDS, these two methods presents the most efficient ways to engage radicals when compared to the other sampling technics.

References

Aase, T. H. (2014). The Grammar of Honour and Revenge.

Acharya, A. K. (2007). A methodological approach to study hidden populations: The case of trafficked women in Mexico City. International Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 9-23.

Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update.

Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 7-36. doi:10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.1

Corbie-Smith, G., Moody-Ayers, S., & Thrasher, A. D. (2004). Closing the Circle Between Minority Inclusion in Research and Health Disparities. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(13), 1362-1364. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.13.1362

Faugier, J., & Sargeant, M. (1997). Sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(4), 790-797. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00371.x

Ferreira, L., Oliveira, E., Raymond, H., Chen, S., & McFarland, W. (2008). Use of Time-location Sampling for Systematic Behavioral Surveillance of Truck Drivers in Brazil. AIDS and Behavior, 12(Supplement 1), 32-38. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9386-0

Goel, S., & Salganik, M. J. (2009). Respondent‐driven sampling as Markov chain Monte Carlo. Statistics in Medicine, 28(17), 2202-2229. doi:10.1002/sim.3613

Handcock, M. S., Gile, K. J., & Mar, C. M. (2014). Estimating hidden population size using respondent-driven sampling data.

Harned, M. S. (2004). Does It Matter What You Call It? The Relationship Between Labeling Unwanted Sexual Experiences and Distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1090-1099. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1090

Hay, G., & Gannon, M. (2006). Capture–recapture estimates of the local and national prevalence of problem drug use in Scotland. International Journal of Drug Policy, 17(3), 203-210. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2004.07.005

Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems(Social Problems), 174–199.

Heckathorn, D. D. (2002). Respondent driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Sociological Problems.

Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate Crimes and Stigma-Related Experiences among Sexual Minority Adults in the United States: Prevalence Estimates from a National Probability Sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54-74. doi:10.1177/0886260508316477

Hope, V. D., Hickman, M., & Tilling, K. (2005). Capturing crack cocaine use: estimating the prevalence of crack cocaine use in London using capture-recapture with covariates. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 100(11), 1701. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01244.x

Kendall, C., Kerr, L., Gondim, R., Werneck, G., Macena, R., Pontes, M., . . . McFarland, W. (2008). An Empirical Comparison of Respondent-driven Sampling, Time Location Sampling, and Snowball Sampling for Behavioral Surveillance in Men Who Have Sex with Men, Fortaleza, Brazil. AIDS and Behavior, 12(Supplement 1), 97-104. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9390-4

Lambert, E. Y. (1990). The Collection and interpretation of data from hidden populations (Vol. 98). Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services.

Mackellar, D., Valleroy, L., Karon, J., Lemp, G., & Janssen, R. (1996). The young men’s survey: Methods for estimating HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Rep., 111, 138-144.

Magnani, R., Sabin, K., Saidel, T., & Heckathorn, D. (2005). Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. Aids, 19, S67-S72.

Medhi, G., Mahanta, J., Akoijam Brogen, S., & Adhikary, R. (2012). Size estimation of injecting drug users (IDU) using multiplier method in five Districts of India. Substance Abuse Treatment, 7(1), 9. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-7-9

Moghaddam, F. M. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: a psychological exploration. Am Psychol, 60(2), 161-169. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.161

Neumann, P. (2008). Perspectives on Radicalisation and Political Violence. Retrieved from London:

Petersen, R. D., & Valdez, A. (2005). Using Snowball-Based Methods in Hidden Populations to Generate a Randomized Community Sample of Gang-Affiliated Adolescents. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 151-167. doi:10.1177/1541204004273316

RAGAZZI, D. B. a. L. B. a. E.-P. G. a. F. (2014). Preventing and Countering Youth Radicalization in the EU. doi:10.2861/62642

Richard, B., Brian, K., & Donald, Y. (2011). Counting the Homeless in Los Angeles County.

Salganik, M., & Heckathorn, D. D. (2004). Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 2004, Vol 34, 34, 193-239.

Shaghaghi, A., Bhopal, R. S., & Sheikh, A. (2011). Approaches to Recruiting ‘Hard-To-Reach’ Populations into Re-search: A Review of the Literature. Health promotion perspectives, 1(2), 86. doi:10.5681/hpp.2011.009

Shedlin, M., Decena, C., Mangadu, T., & Martinez, A. (2011). Research Participant Recruitment in Hispanic Communities: Lessons Learned. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(2), 352-360. doi:10.1007/s10903-009-9292-1

Silber, M. D., & Bhatt, A. (2007). Radicalization in the West: The Homegrown Threat. Retrieved from New York City:

Valdez, A., & Kaplan, C. D. (1998). Reducing Selection Bias in the Use of Focus Groups to Investigate Hidden Populations: The Case of Mexican-American Gang Members from South Texas. Drugs & Society, 14(1-2), 209-224. doi:10.1300/J023v14n01_15

Vogt, W. P. (2005). Dictionary of statistics & methodology : a nontechnical guide for the social sciences (3rd ed. ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

Watters, J. K., & Biernacki, P. (1989). Targeted Samplings: Options for the Study of Hidden Populations. Social Problems.

Williams, M., & Cheal, B. (2002). Can we measure homelessness? A critical evaluation of the method of ‘capture-recapture’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 5(4), 313-331. doi:10.1080/13645570110095346

[*] Ömer Faruk Sazak is a PhD candidate at the University of Stavanger. His research deals with «radicalisation» and different de-radicalisation programs in Europe.

[1] Andres Behrig Brevik killed 77 people with his bombing and mass shooting attack in Oslo and Utoya Island in 22 July 2011.

[2] Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhleh drove the truck into the crowd while they were celebrating the Bastille day in Nice in 14 July 2016. 86 were killed and 458 were injured in this terror attack.