Key Takeaways

- Geostrategic Leverage: Pakistan’s location at the intersection of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East, along with access to the Arabian Sea through Gwadar Port, positions it as a critical hub for maritime trade, energy routes, and great power competition.

- China’s Strategic Pillar: Beijing views Pakistan as an anchor for the Belt and Road Initiative, investing heavily in CPEC infrastructure and championing an “all-weather strategic cooperative partnership.” However, growing security risks, trade imbalances, and hesitancy over military basing rights temper China’s ambitions.

- Security-Driven Alignment: China provides Pakistan with advanced military equipment and diplomatic support, while pressing Islamabad to ensure the safety of Chinese personnel amid frequent insurgent attacks—revealing a relationship of deep engagement but increasing demands.

- Transactional U.S. Engagement: U.S. relations with Pakistan have fluctuated from Cold War ally to post-Afghan disengagement. Under Trump’s 2025 administration, renewed interest centers on critical minerals, trade, and geopolitical calculus rather than long-term alliance building.

- Critical Minerals and Economic Interests: The U.S. seeks access to Pakistan’s antimony and rare earths to reduce reliance on China. Trade negotiations, including tariff relief, reflect this growing economic convergence—but remain transactional and politically contingent.

- Pakistan’s Hedging Strategy: Islamabad seeks to balance ties with both China and the U.S., leveraging each for economic and diplomatic gains. This hedging yields short-term benefits but increases exposure to external shocks and geopolitical rivalry.

- Limits of Strategic Depth: Despite its value, Pakistan faces limitations: China’s security concerns slow investment; the U.S. offers little structural aid; and domestic instability complicates long-term partnerships. Future influence hinges on Islamabad’s ability to manage risk and assert coherent strategic policy.

Introduction

Pakistan occupies a pivotal geographical position at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. Its 1,046‑km coastline along the Arabian Sea lies close to the Strait of Hormuz, through which roughly 80 % of the world’s oil trade passes. The deep‑water Gwadar Port gives access to the Persian Gulf and provides land‑locked Central Asian states and western China a direct sea route that bypasses the Malacca Strait. These attributes make Pakistan a significant node for global supply chains, maritime security and competing great‑power strategies.

The country’s strategic value is magnified by its nuclear capability, its influence over security dynamics in Afghanistan and Kashmir, and its large population (240 million). It is also a key player in the global war on terror and a gateway for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The United States and China – two rivals vying for influence across Eurasia – view Pakistan through different lenses shaped by their geopolitical objectives. This analysis examines how Washington and Beijing regard Pakistan’s strategic importance. It focuses on high‑level contacts, initiatives and narrative framing to reveal convergences and divergences in the two powers’ approaches.

China’s Perspective: Pakistan as a BRI Pillar and Strategic Partner

Gwadar Port and CPEC: A Gateway to the Arabian Sea

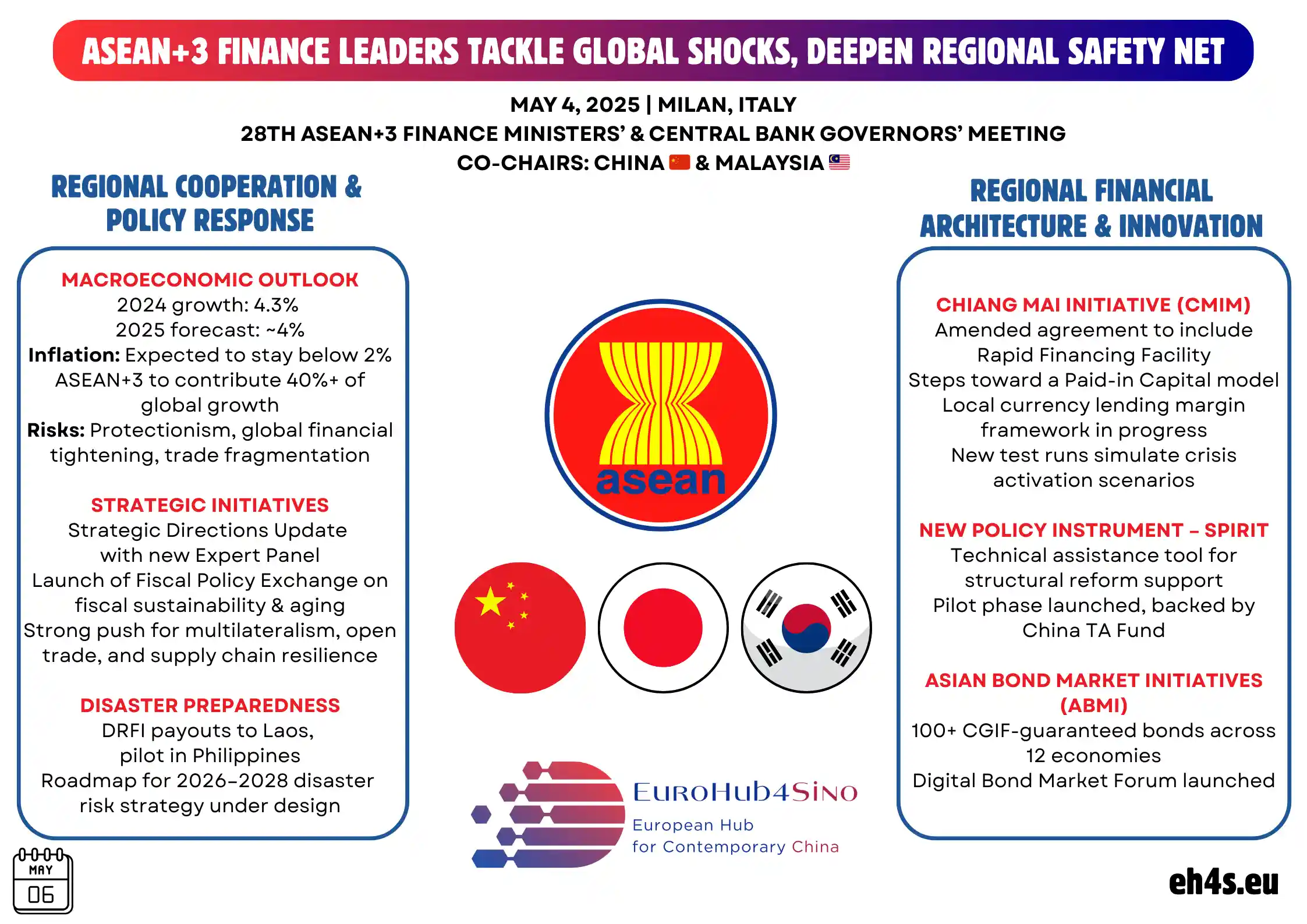

Beijing sees Pakistan as an indispensable partner in its Belt and Road Initiative because the China‑Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) connects China’s western regions to the Arabian Sea. Gwadar Port, developed by China and operated by Chinese state‑owned enterprises, provides China “direct access to the Arabian Sea, bypassing the Malacca Strait” and serves as a gateway to Central Asia and the Middle East. The port’s proximity to the Strait of Hormuz increases its strategic value for energy security and maritime trade.

CPEC includes highways, rail lines, energy pipelines and industrial zones linking Gwadar to Kashgar in Xinjiang. In October 2024 a joint statement released during Premier Li Qiang’s visit to Islamabad reaffirmed that both governments considered their relationship “rock‑solid” and committed to upgrading CPEC by building “growth, livelihood, innovation, green and open corridors,” improving the Main Line‑1 railway (ML‑1) and enhancing Gwadar Port. Pakistan reiterated support for China’s “one‑China” principle and Beijing reciprocated by pledging to safeguard Pakistan’s sovereignty and national security. China’s willingness to invest billions of dollars into infrastructure reflects its belief that economic connectivity can expand influence and secure an overland route for its imports and exports.

All‑Weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership

Since the 1960s, Beijing and Islamabad have described their partnership as an “all‑weather” relationship built on shared opposition to India. In a June 2024 meeting, President Xi Jinping called Pakistan a “good neighbour, good friend, good partner and good brother.” He pledged that China would continue supporting Pakistan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and help it combat terrorism. Xi emphasised synergy between BRI and Pakistan’s development plans, urging cooperation in agriculture and mining and promising to build five corridors for an “upgraded CPEC”. The Pakistani side re‑affirmed the one‑China principle and expressed readiness to protect Chinese interests.

High‑level contacts continued throughout 2025. In February President Asif Ali Zardari paid a state visit to Beijing, where he and Xi discussed accelerating CPEC projects, expanding trade and investment, and enhancing defence and technology cooperation. A Chinese article noted that the visit produced agreements to “boost digital innovation and academic exchanges” and emphasised that Pakistan’s location gives China “a gateway to the Arabian Sea”. Bilateral trade data highlight Pakistan’s growing economic dependence on China: in 2024 China’s exports to Pakistan reached US$20.2 billion (up 11.1 % from 2023), while imports from Pakistan fell to US$2.8 billion. Pakistan mainly sells copper and cotton to China, underscoring a structural trade imbalance.

Security Cooperation and Challenges

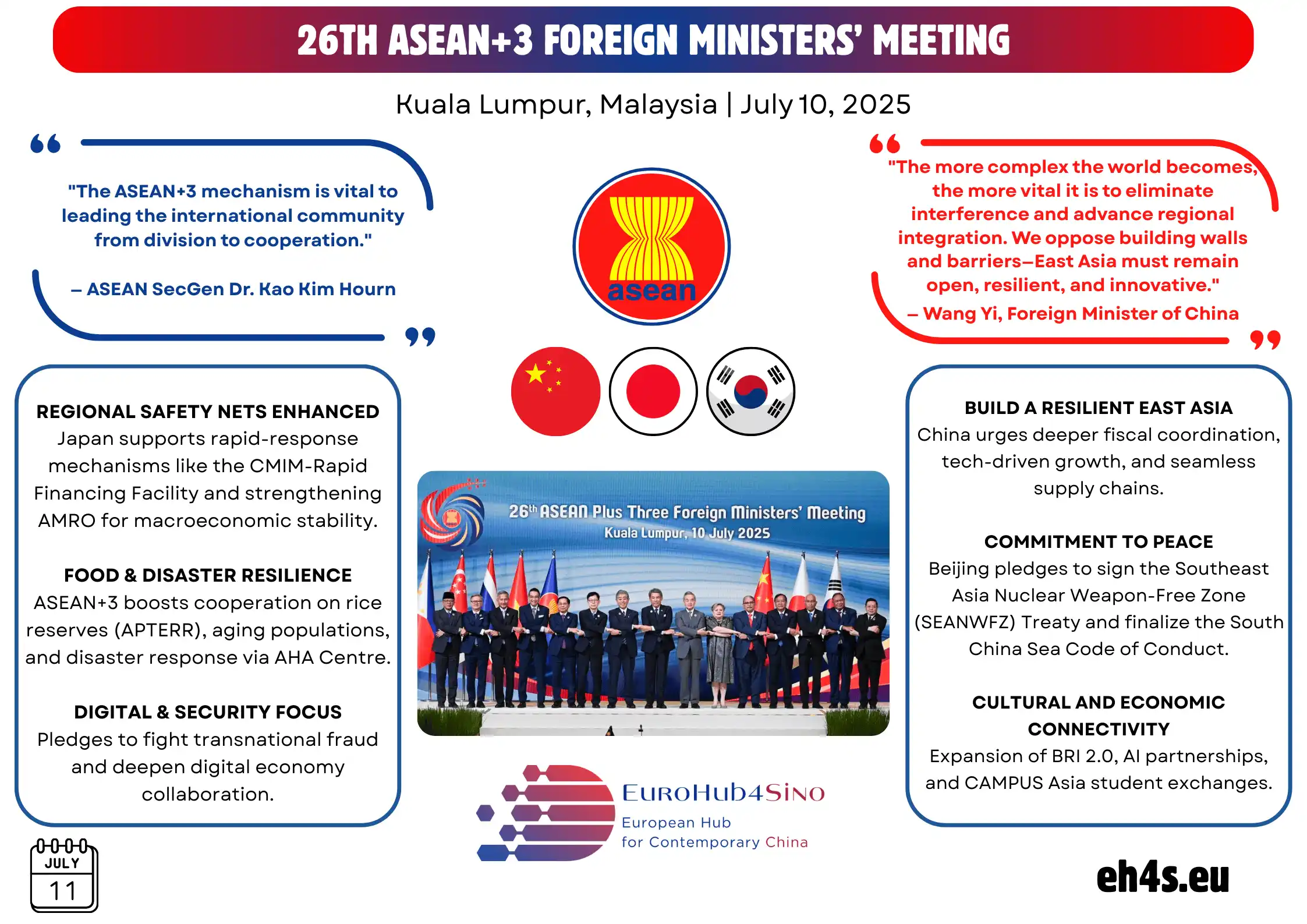

Security cooperation is a cornerstone of the relationship. China provides Pakistan with advanced military hardware, from combat aircraft and naval frigates to surface‑to‑air missiles. Beijing also endorses Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent vis‑à‑vis India. In July 2025 China’s top diplomat Wang Yi met Pakistani army chief General Asim Munir in Beijing. He called the Pakistani military a “staunch defender of national interests” and said China was ready to implement leaders’ consensus and deepen all‑weather cooperation. Wang praised Pakistan’s efforts to combat terrorism and urged its military to ensure the safety of Chinese personnel, projects and institutions. Munir responded that cooperation with China enjoyed consensus in Pakistani society and promised to safeguard Chinese nationals and strengthen counter‑terrorism cooperation.

Despite this camaraderie, security concerns strain the partnership. Insurgents in Balochistan and Sindh have repeatedly attacked Chinese engineers and workers on CPEC projects. A RAND commentary from early 2025 observed that Beijing publicly rebuked Islamabad after such attacks, with the Chinese ambassador insisting that Pakistan “severely punish” perpetrators. It noted that China delayed investments like the ML‑1 railway due to security lapses and demanded the right to deploy its own security personnel in Pakistan. There have also been tensions over potential Chinese military access to Gwadar. Pakistani officials reportedly sought to prevent China from obtaining a permanent naval presence and even denied a port call under U.S. pressure. These episodes reveal a pragmatic calculus in which China’s economic ambitions are tempered by concerns about safety and strategic overreach.

Diplomatic Support and Regional Implications

China backs Pakistan diplomatically on issues such as Kashmir, counterterrorism and relations with Afghanistan. Beijing often defends Islamabad in international forums when India raises terrorism concerns. In return, Pakistan champions China’s positions on Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and the South China Sea. This mutual support buttresses each regime’s narratives and demonstrates their alignment against Western criticism.

For China, Pakistan serves as a counterweight to India and a bridge to the Muslim world. The South Asia Monitor notes that Pakistan’s location along the Indian Ocean sea lines of communication is a “strategic lifeline” for global energy flows. Participation in joint naval exercises and efforts to build a blue‑water navy help Islamabad contribute to maritime security, but Beijing also views these activities as complementing its own maritime strategy. At the same time, Pakistan attempts to balance between China and the U.S.‑led Indo‑Pacific framework.

The United States’ Perspective: From Cold‑War Ally to Transactional Partner

Historical Background and Post‑Afghanistan Drift

U.S. policy toward Pakistan has oscillated between strategic embrace and disinterest. During the Cold War, Washington saw Pakistan as a bulwark against Soviet expansion and channelled military and economic aid through alliances such as SEATO and CENTO. In the 1980s Pakistan was the frontline state supporting Afghan mujahideen against Soviet forces. After 9/11 it became a major non‑NATO ally in the war on terror, receiving billions in aid and weaponry.

This relationship eroded after the U.S. invasion of Iraq and Pakistan’s alleged support for Taliban insurgents. The Lawfare Institute notes that by the time President Joe Biden took office (2021‑25) the relationship had reached a “low” due to lack of interest. Biden never called Pakistan’s prime minister and maintained only limited agency‑level engagement. Some initiatives existed – such as a Green Alliance framework focusing on climate, a health dialogue and humanitarian assistance during Pakistan’s 2022 floods – but they were modest. With the war in Afghanistan over, Washington lost its central reason for engaging Pakistan. Although U.S. military commanders continued to visit – the CENTCOM head visited five times in four years – these interactions were largely transactional. The article concludes that Pakistan is no longer a high‑priority partner and relations are likely to remain limited.

Trump’s Second Term and the White House Lunch

The return of Donald Trump to the presidency in January 2025 brought unexpected attention to Pakistan. In June 2025 he hosted Pakistan’s army chief Field Marshal Asim Munir for a two‑hour lunch at the White House. According to Reuters, this was the first time a U.S. president had hosted the head of Pakistan’s army – widely considered the country’s most powerful figure – unaccompanied by senior civilian officials. Trump said he was “honoured” to meet Munir and claimed he had “stopped the war” between India and Pakistan by persuading both sides to agree to a ceasefire. He told reporters that the conflict “could have been a nuclear war” and praised Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi for cooperating.

Pakistan’s military said the meeting discussed trade, economic development and cryptocurrency. Trump’s interest in crypto appeared linked to Pakistan’s “crypto diplomacy”: the Lowy Institute notes that Pakistani leaders established a Crypto Council, appointed a minister for crypto and signed a deal with a company connected to Trump family interests. Pakistan even nominated Trump for a Nobel Peace Prize for halting the India‑Pakistan war. The symbolism of the lunch signaled a temporary “romance” between Islamabad and Trump, reminiscent of his earlier engagement with Prime Minister Imran Khan during peace talks with the Taliban. It also caused consternation in New Delhi; India firmly denied any U.S. mediation in the ceasefire, emphasising that the ceasefire resulted from direct military contacts and rejecting the idea of third‑party mediation. Yet Pakistan publicly thanked Washington for playing a role, demonstrating its willingness to leverage U.S. involvement when convenient.

The meeting highlights the transactional nature of U.S.-Pakistan relations. Trump expected Pakistan’s cooperation on Iran and terrorism; Reuters reports that he and Munir discussed tensions with Israel and Iran, while Pakistani officials hoped the U.S. would avoid striking Iran. Pakistan’s role as the protecting power for Iranian interests in the U.S. gives it a unique niche in Middle East diplomacy. Trump also expressed a desire for a trade deal with Pakistan, acknowledging Pakistan’s critical minerals and emphasising “long-term strategic convergence”. This suggests that the U.S. views Pakistan primarily through the lens of immediate problem‑solving and resource access rather than as a long‑term ally.

Engagement on Trade and Critical Minerals

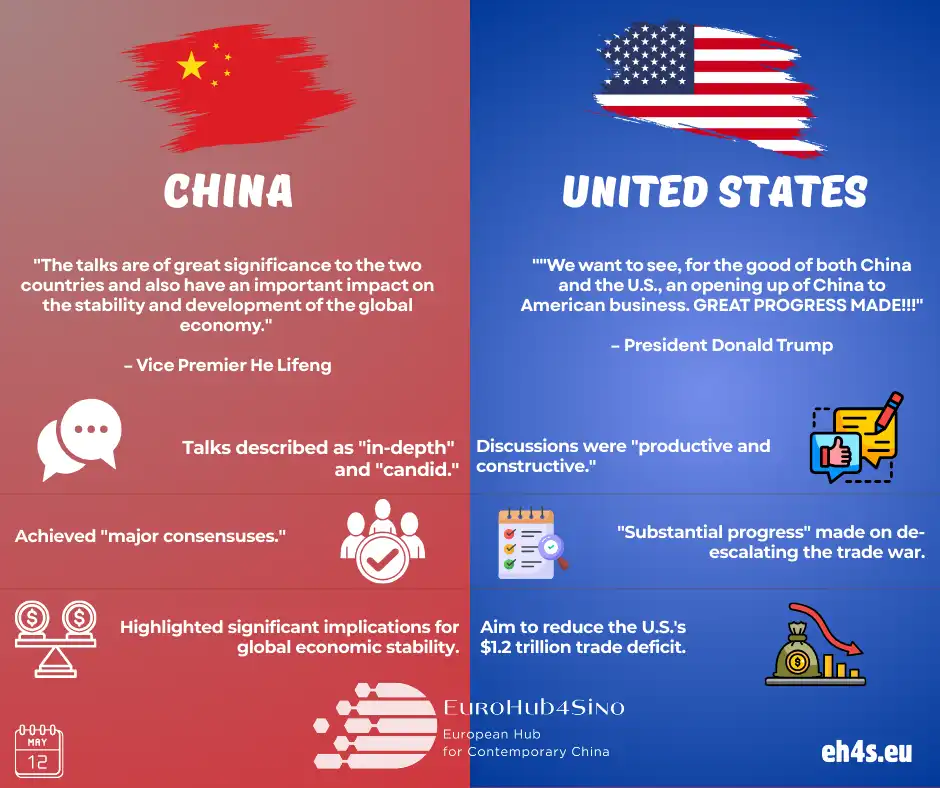

Pakistan has been negotiating with Washington to mitigate a 29 % tariff on its exports imposed by Trump’s 2025 tariff regime. In April 2025 U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio phoned Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar to discuss tariffs, trade relations and critical minerals. Reuters reports that Rubio proposed expanding commercial opportunities for U.S. companies in Pakistan and expressed interest in “critical minerals”. The Pakistani foreign ministry said both sides wanted to collaborate on trade and minerals, reflecting how the U.S. is seeking alternative sources of minerals essential for batteries, semiconductors and defence technologies. Pakistan is thought to hold deposits of antimony, lithium, cobalt and rare earths. Pakistan offered antimony to the U.S. as part of a broader attempt to curry favour with Trump.

Following the phone call, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar visited Washington in July 2025. Reports from BDDigest note that he met Rubio to discuss strengthening trade relations, reducing tariffs and increasing cooperation on critical minerals. Dar told reporters he was close to finalising a trade deal with the U.S. “within days” and that Pakistani experts were working to mitigate the 29 % tariff. Rubio acknowledged that the U.S. saw Pakistan as a constructive partner and was interested in minerals and investment. Another Arab News article describing the same meeting emphasised that Rubio recognised Pakistan’s “constructive role” in regional peace and that the meeting was the first between the countries’ top diplomats in nine years. The U.S. also seeks Pakistan’s help on immigration and law enforcement issues, including controlling flows of migrants and countering illicit drugs.

This focus on trade and minerals reflects a broader shift in U.S. strategy. With supply chains in flux and reliance on China for critical minerals becoming a vulnerability, Washington is looking for alternative partners. Pakistan’s geology offers potential, but extracting and processing these resources would require significant investment and security assurances. The U.S. also frames engagement as part of its Indo‑Pacific strategy: cooperating with Pakistan could complement efforts to counter China’s influence, but it must be balanced against Washington’s deepening partnership with India.

Limited Structural Support and Societal Perceptions

Unlike China, the U.S. does not offer Pakistan large‑scale infrastructure investment. American aid has declined sharply; economic assistance fell from billions in the 2000s to only hundreds of millions of dollars in recent years. When disasters strike – such as the 2022 floods – Washington provides humanitarian assistance, but long‑term development programmes remain limited. The Lawfare article argues that U.S.-Pakistan relations have settled into a “low‑level equilibrium” where engagements are sporadic and transactional. Even military cooperation, once the backbone of the relationship, is narrow: the United States still provides limited training and equipment but has suspended major security assistance since 2018 over concerns about Pakistan’s alleged support for militants.

Societal perceptions also matter. Pakistan’s political elites sometimes see the U.S. as fickle and disrespectful of their sovereignty. Anti‑American sentiment spiked after U.S. drone strikes and the 2011 raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad without prior notification to Pakistan. While cooperation continues in counterterrorism, many Pakistanis believe the U.S. focuses on its own objectives with little regard for Pakistan’s domestic stability. On the American side, policymakers and the public often view Pakistan as double‑dealing – accepting aid while harbouring militants. These mutual suspicions limit trust and shape the transactional nature of the relationship.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s strategic importance for both the United States and China stems primarily from its geography and its role in regional security. For China, Pakistan is a cornerstone of the Belt and Road Initiative and a trusted strategic partner. Beijing invests heavily in Pakistan’s infrastructure and views Gwadar Port as a gateway to the Arabian Sea and global markets. High‑level visits and joint statements emphasising an “all‑weather strategic cooperative partnership” underscore the depth of the relationship. Yet this partnership faces headwinds from security threats, trade imbalances and latent tensions over the extent of China’s military presence.

For the United States, Pakistan’s importance is more conditional. The end of the Afghan war reduced Pakistan’s centrality, and under President Biden the relationship became a low‑level engagement characterised by limited initiatives. Trump’s return triggered high‑profile outreach, including an unprecedented White House lunch with Pakistan’s army chief and discussions of trade and critical minerals. Yet these gestures are transactional, tied to short‑term crisis management and resource interests. U.S. policymakers remain wary of Pakistan’s ties to China and its history of tolerating militant groups.

Ultimately, Pakistan seeks to harness its strategic position to maximise autonomy and economic gains. It courts investment from China while negotiating tariffs and mineral deals with the U.S. and maintaining working relations with India, Iran and the Gulf. This hedging strategy yields benefits but exposes Pakistan to the vagaries of great‑power rivalry and domestic instability. Whether Pakistan can continue balancing between Beijing and Washington will depend on its ability to address security challenges, sustain economic reform and craft a coherent foreign policy that transcends short‑term political calculus.

Related Infographics