Abstract

Social networks play a vital role as a source of information for immigrated people and affect many aspects of their lives. They provide access to information, for example about jobs and conditions in the host country. This article intends to highlight the experiences of the MESH project regarding the importance and challenges of social networks for immigrants in Finland and Belgium. The findings of the article are based on the piloting experiences of the network models developed by the MESH partners. This is a case study in which various methods of qualitative research have been used. The paper finds that cultural gaps and language problems are the major impediments to building social networks and they can be faced and diminished by systematic and patient networking practices.

Keywords: Immigrants, integration, employment, social networking, networking model.

* This article is written with the financial support of European Social Funds (ESF), Finnish and Flemish Governments; by the partnership of Turku University of Applied Sciences, LAB University of Applied Sciences and Tampere University of Applied Sciences from Finland; Economic House of Ostend and Beyond the Horizon ISSG from Flanders, Belgium.

Essi Hillgren[1], Janna Peltola[2], Fatih Yilmaz[3], Nasrin Jahan Jinia[4], Ulla-Maija Koivula[5]

1. Introduction

Immigrants face various challenges to start a new life in a different society. Building a network and finding useful information about the labour market are the main challenges. Nowadays most of the jobs, especially in the private sector, are not well circulated or advertised. An effective way to know about jobs is through networking and connecting with the people. Therefore, it is important to develop networks with the people of the host country. Networking is a useful tool for empowering and integrating immigrants through getting information, making friends, and learning about new cultures. And all these promote the process of a better functioning society and sustainable development.

Social networking is identified as a key to immigrants’ economic and social success in destination countries. Social networking also helps accelerate their integration process and assists to utilize their expertise effectively. It is obvious that social networking is not only concerned with employment or career, it also helps one find new social circles or companions, shows one’s own expertise or interests to the people, and acquaints them with the cultural rules and social norms of a host country.

Highlighting the importance of networks, the MESH international project,[6] “Employing immigrants via networks and mentoring”, has been working to empower immigrants and jobseekers through networking and mentoring since January 2019. The goal of the project is to develop, experiment and distribute models and practices of mentoring and networking. The duration of the project funded by European Social Fund is between 1/2019 – 12/2021.

The partner organizations of the MESH project from Finland are Turku University of Applied Sciences, LAB University of Applied Sciences and Tampere University of Applied Sciences. The Belgian partners are HIVA KU Leuven, Economic House of Ostend and Beyond the Horizon ISSG.

One of the main aims of the MESH project is to develop networking models to empower immigrants. During the last 2,5 years, the partner organizations of this project developed three models of networking:

- Networking steps model by Tampere University of Applied Sciences, Finland

- Model for organizing mentoring initiatives by the Economic House of Ostend, Belgium

- “All-in-one 4 HER” digital networking model by Beyond the Horizon ISSG, Belgium

This article intends to introduce the mentioned networking programmes of the MESH project and summarise the findings of their pilots in Belgium and Finland. It also shortly explains the importance of social networks for jobseeker immigrants.

2. Networking and Its Importance in Employment

Networking is considered to be one of the key skills for successful job search and career building. For many immigrants, however, finding professional networks in a new home country can be very challenging. Language is a strong barrier for them to build a network and get into the labour market. Cultural communication styles can vary, even if there is a common language to converse with.

Networking as a concept has been used since the early 20th century to describe complex sets of relationships between people as well as organisations. Castells (2004, 3) named our society as a ‘networking society’ whose social structure is made up of networks powered by communication technologies. While social networks have always existed, networks today are more diverse and are extremely strengthened by social media and the internet.

Networks have been defined as a group of units connected with ties. Units can be people, organizations or states (Castells, 2000). Network concept is versatile and can also refer to a certain organizational form between independent organizations. Thus, networks can be interpersonal or interorganizational. In this article we concentrate on interpersonal networks.

Social networks are seen as social capital (compared with human capital, educational capital, cultural capital, economic capital) (Coleman, 1988). Social capital refers to norms of reciprocity and trust. Some scholars see social capital more as an individual property, others more as a community property. For Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992, 119) social capital is “the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition”. They consider social capital as a personal asset in the competition among individuals aiming to improve their own position vis-à-vis others.

Social networking and social capital have become more important in working life due to fragmented and flexible working life structures. Collaboration and project-based working has been increased. Precarious work, fixed term contracts and “limitless careers” are more prevalent. Many job opportunities are not even published officially, but either internally, via social networks or social media. In today’s job market, more than half of the job vacancies are not made public. It is estimated that 75% of posts for jobs are generally filled though the hidden job market (CareerLink, 2015). Networking is considered as one of the most effective tools to get access to the hidden part, which makes developing networks especially important and necessary for immigrants.

3. Methodology

The study adopts qualitative methods with the combination of an explanatory and descriptive case study, interviews, and participant observation to accomplish it. Case study is a preferred method because it allows for the simultaneous investigation of how, what, and why questions in a real-life context, where the researchers have limited control over events (Yan, 1994). Thus, the case study method helps develop a holistic understanding of immigrants’ networking.

The primary data has been collected from different stakeholders and the target group such as immigrants (male & female), project workers and officials working in this field during and after the piloting of the models. The field data has been analysed in a descriptive manner.

4. Networking Steps Model (Finland)

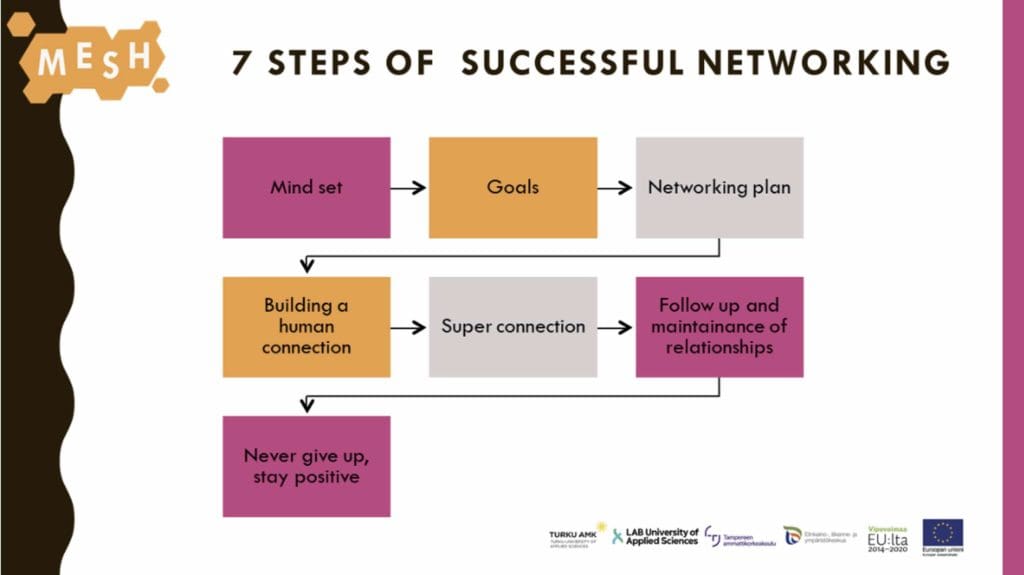

As one of the partners of the MESH international project, the team of Tampere University of Applied Sciences has developed the “Networking Steps Model”. The model recommends seven steps to create or develop a successful network. The steps are: 1) Mindset; 2) Goal setting; 3) Networking action plan (NAP); 4) Building a human connection; 5) Super connecting; 6) Follow-up and maintenance of relationships; and 7) Never give up and be positive.

The steps are interrelated and interdependent, but each step is guided by its own tools, activities, tips, and links which contribute to creating a successful network (see Figure 1). The tools and activities of each step are easy to understand and follow.

- The first step “Mindset” helps in creating a productive mindset through various tools and activities. According to Baker (2000), social capital is created as the resources are available to an individual because of his or her personal relationships. Strong self-motivation, willingness and self-confidence are essential for a mindset in network building.

- “Goal setting” is considered the second step, which clarifies a person’s aims and provides a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of the process. It motivates one to work and creates intentional focus. Goal setting is based on personal importance and self-efficacy (Locke & Latham 2002; Latham and Locke 2006; Schöttle & Tillmann 2018).

- The third step, “networking action plan”, starts when the goals are known and defined. The plans must be realistic and achievable. With a timeline or milestones, you can track progress when different goals need to be achieved (Garcia, 2016).

- The fourth step deals with the “human connection”, either face to face or virtually, depending on the goals and action plan. Building relationships with others leads to a broader network, which can strengthen social support as well as provide useful ideas and advice (de Janasz & Forret 2008).

- The fifth step, “super-connecting”, consists of tools and tips that help in finding the people with strong connections. However, weak connections may also help in finding strong connections.

- The sixth step is about “following up and maintaining the relationship”. It’s difficult to develop a network without regular and continuous follow-up, which helps with building trust and confidence among the stakeholders.

- The final step, “never give-up and stay positive”, motivates one to keep going, even though one might face some adversity during the process. After completing the exercises, networks likely become stronger. They might help immigrants find a job or better connect with a new society.

More details about the steps model are available here: https://networking2work.weebly.com/steps.html

Figure 1. Networking Steps Model (Developed by MESH, 2020)

The MESH project team of Tampere University of Applied Sciences piloted the steps model online during autumn 2020 and spring 2021. The multicultural piloting groups were developing their networks in order to get acquainted with the Finnish society and job market. According to collected feedback, the workshops opened participants’ eyes for possibilities of effective networking and finding information about hidden jobs.

Most of the participants expressed that the content of the programme had met their expectations, even though face to face workshops might have been more fruitful ways to develop networks. Overall, the participants were happy with the discussions during the sessions, and they found the provided materials useful. Nevertheless, challenges during the pilot had to be met, while the world was dealing with pandemic and strict assembly restrictions. Availability and intention of participants varied especially during the second pilot in spring 2021.

In Spring 2021, the networking step model was piloted in the Turku region too. The pilot was divided into four workshops based on different networking phases: mindset & goal setting, action plan, creation of relationships, and maintenance of relationships. Participants were highly educated people with immigrant backgrounds. A common target for the participants was to find their way to the Finnish job market.

Based on the collected feedback, participants were satisfied with the content, process, way to work, and the group in general. The workshops met expectations and offered support and tools for networking. The overall grade for the networking pilot was 8,5/10.

Finnish MESH project has also carried out several career mentoring programmes for international talents. The aim of the programmes is to support international talents, known as mentees, towards Finnish labour markets. Mentoring can support them in recognizing their career opportunities, skills and development areas, as well as understanding networking and working life in Finland with the help of experienced mentors. Mentors and mentees who participated have been interviewed and below are the major findings about how they see networking in Finland.

During the group discussions at the workshops, participants learned a lot from each other, and peer support encouraged them to develop their networks and networking skills. One of the participants said “I am not alone in not knowing how to network. I am more willing to look into networking.” After the workshops, participants felt more confident doing networking activities and they felt more relaxed with networking in general. They felt that networking was not as complicated as they used to think because now they have a better understanding about methods and tools to widen their networks.

Participants wished to learn more about cultural aspects and differences in networking. Different personalities were an interesting topic in discussion and participants wished to have more content related to that.

5. Model for Organising Networking Initiatives (Belgium)

This model is developed by the Economic House Ostend, a city organization where job seekers get support in their job search. The target groups of the Economic House are adult job seekers with a migration background and NEET youth (youth not in employment, education or training). Some of the strengths of Economic house are the multi-disciplinary team and their hands-on flexible approach.

The modules created by Economic House enhance learning in the context of job application skills and orientation to the labour market through guided job applications during an open learning centre, individual coaching, and a driver’s license programme. The House also organises different networking initiatives such as a job application afternoon session with temporary employment agencies and information sessions for people who are distant from the labour market. The House has taken some additional initiatives in building trust among the jobseekers with migrant backgrounds, such as accessibility of counsellors, an open door policy and a solution-oriented attitude. They aim to look for additional initiatives to increase the confidence of the clients.

The Economic House of Ostend is developing a professional network model and practical guide. Both instruments are being developed through a combination of theoretical starting points and practical experiences of the Economic House. The model outlines a gradual and phased process that will help service organisations with the same mission as Economic House in order to stimulate, broaden and finally activate a professional network of jobseekers with migrant backgrounds. The intended result is to create employment opportunities.

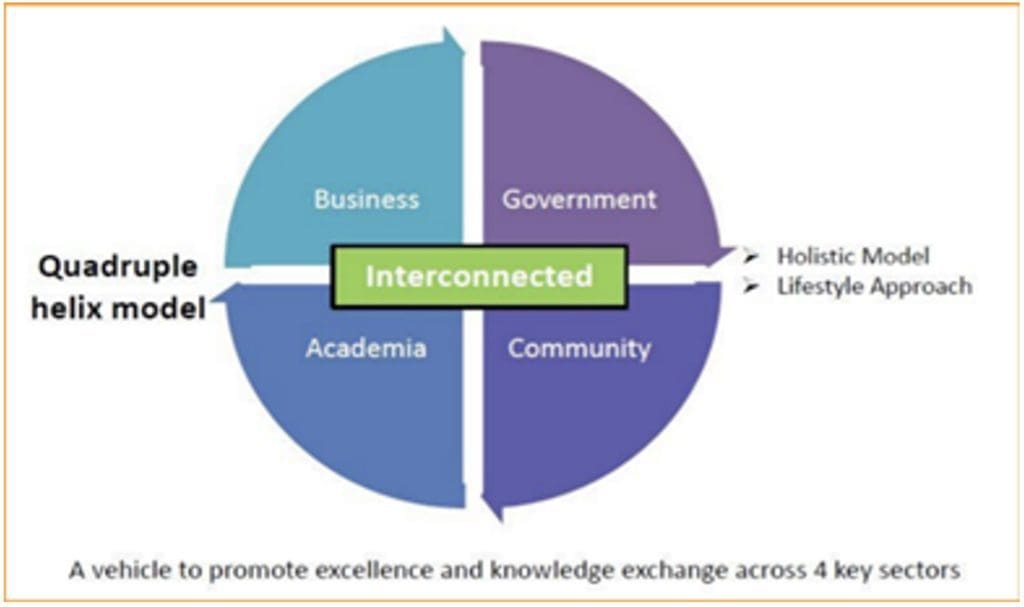

The theoretical starting point for developing a model for organising networking initiatives was ‘The quadruple Helix model’. It’s been assumed that the gradual process can be qualitative if service organisations collaborate closely with each other. In practices of the model, the policy and educational staff visualize their (potential) partners. The needs of the clients are central in every activity. This holistic model is based on the collaboration of four actors such as government, academia, business & community. Due to a collaboration between the four various actors, a synergy effect is created (see Figure 2).

On the other hand, a criteria checklist is developed for organising the networking initiatives which includes the following factors: communication, accessibility, trust, focus on bridging, equality and added value.

Read more about the model here: https://networking2work.weebly.com/for-organizations.html

Figure 2. (Quadruple Helix) Model for organising networking initiatives (Carayannis & Campbell, 2009).

Economic House Ostend, Belgium has arranged different types of networking activities with individuals from migrant backgrounds. At the end of March 2021, the total number of participants who finished coaching to work was 874, and the number of participants in active coaching was 147. The success rate of the completed job coaching was 73 percent.

In general, job coaches of the Economic House also face some obstacles, such as lack of vacancies in the region and a large number of temporary job contracts. In most cases, job seekers with low skills received a temporary job contact, especially during the COVID-pandemic. Quite often a temporary job contract lowers motivation of the client. The professional network of people with a migrant background is often small and they do not always see the benefits of professional networking.

When a job seeker has no intrinsic motivation to find a long-term job or is struggling with social problems (e.g., homelessness), he or she does not come to appointments. In such situations, it is difficult to help the job seeker. Nevertheless, there are also many success stories[7].

6. Digital Networking Model on a Platform (Belgium)

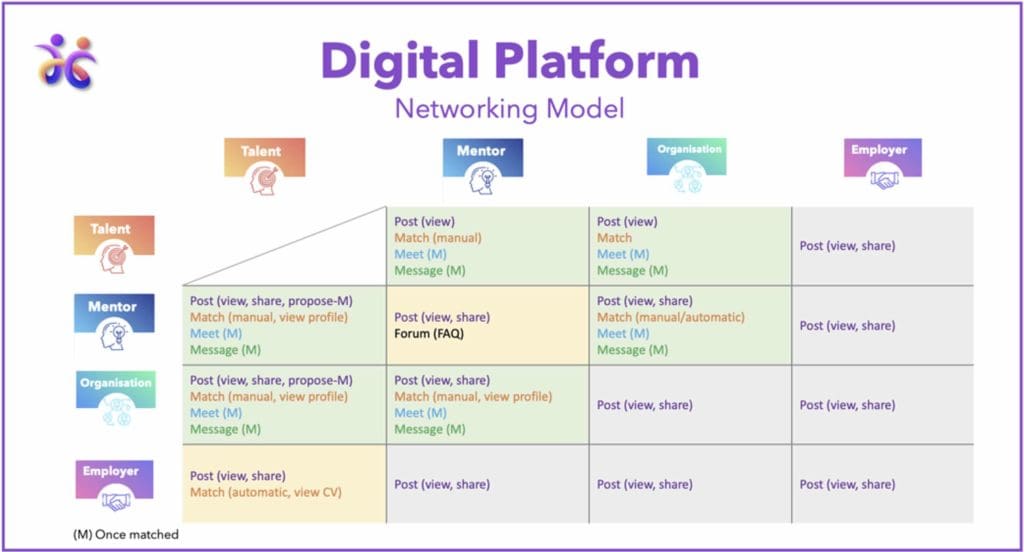

Beyond the Horizon ISSG has developed a digital platform[8] and an application[9] as a part of the ESF project “All-in-one 4 HER – Fast-track integration of highly educated migrants into the labour market” in Flanders, Belgium. The platform aims, among others, to connect migrants to the other regional actors of integration in order to support their networking in their new host country. Platform’s networking model has been developed with the inputs of transnational partners and tested in several provinces of the Flemish region in Belgium.

The digital platform is also mainly based on the quadruple Helix model, which focuses on the actors from academia, government, industry, and civil society to define its users. The four main users of the platform are defined as talent (refugee, migrant), mentor, employer (industry), organisation (academia, government, civil society). The platform gives a central role to migrant users and provides a space for networking and connecting with other users. The platform is built in different languages to mitigate the language barrier for migrants.

The digital platform uses four different main functions to allow networking among the users, namely POST, MATCH, MEET and MESSAGE. The users can share different types of posts on the platform with other users. These are named as S-V-E-P-T posts, including the initial letters of the post types: Study, Vacancy, Event, Project, Tool. This function aims to provide users an open space where they can freely interact, share useful posts, promote their activities and tools or reach out to their target groups. The match function is managed by the platform admin for matching a migrant with a mentor or organisation user. It allows the users to see each other’s profiles and to use the other two functions, meet and message among each other. Matched users can send messages to each other and also plan their meetings and activities on the platform, which actually makes up a log of their activities. See Figure 3 for the digital networking model.

Find more details about the digital networking model and the digital platform on this link: https://networking2work.weebly.com/platforms.html

Figure 3. Digital platform networking model (Developed by Beyond the Horizon ISSG, 2020)

The piloting outcomes can be summarized in a nutshell as follows. The Covid situation increased the attention of immigrants and other users to the digital platform due to the limitations of physical contact. There was more necessity in the use of digital tools and meetings, which also shows the increasing need for digital networking. At this point we need to consider the digitalisation of the integration processes. It’s been experienced that a digital platform can be a good complementary tool for mentoring support in networking and professional networking itself, but it is certainly not a sole tool for networking. On the other hand, it has its own challenges such as data sensitivity and competition in the digital market. Processing sensitive personal data of users, particularly immigrants, is limited by the GDPR. It also limits the networking functions of the platform. Competition in the digital market increases the standards for a digital networking platform and attracting users is difficult in this respect.

7. Key Findings of Networking Programmes in Finland and Belgium

Based on the pilots of networking programmes in Finland and Belgium, some key findings are outlined in this section in terms of common challenges faced by immigrants developing networks in their host society.

Creating or developing networks in a new location is difficult for immigrants for many reasons, especially because of language barriers. It takes time to get familiar with the language. Accessibility and social engagement might be limited when immigrants are not able to communicate with the same language to build or develop a network.

A lack of language proficiency is also a barrier to finding out about resources and events provided by different stakeholders for people coming from different parts of the world to a new society. Immigrants hesitate to communicate with a member in the host society because they are unable to understand their language.

Some cultural barriers have been faced, too. People coming from different cultures may not find comfort in communicating or coordinating easily with one another. When people from different countries come together, their way of thinking varies. Some might be shy while others are outgoing. Because of cultural differences, immigrants often hesitate to develop networks with people in the host countries. Networking is a two-way process, and it will be effective only when each person can understand the other side. Thus, it’s obvious that it is difficult for networking to take place in the presence of any kind of barriers that hinder interaction between the communicators. Cultural barriers reduce effective communication at both personal and professional levels.

The behaviour of people in a host country can be considered as a barrier to effective networking. Culture influences one’s personality and the persona in turn impacts the way one thinks, behaves, and communicates. For example in Finland, quite many Finns do not feel comfortable using English or other second languages. That may keep themselves away from communicating or networking with people coming from different countries.

Lately, because of the pandemic, networking has been mostly virtual. One of the common challenges of virtual networks is that it is too formal. In many cases effective networking happens during informal situations. In face-to-face events, people can see, hear and feel the connection of a person and thereby can more easily sense whether they’re really interested in networking or not. In virtual situations, this can be difficult.

The pandemic has accelerated the necessity for digitalisation of the integration processes including networking programmes. The digital networking model and the digital platform are timely in this respect, but they have their own challenges including data sensitivity and competition in the digital market. GDPR limits the networking functions of the platform, and users might be hesitant to use new digital platforms. Competition in the digital market increases the standards for a digital networking platform and attracting users is also difficult in this respect. But the piloting showed that a digital platform including an application can be a good complementary tool for professional networking and mentor support in networking for immigrants.

Despite limitations, networking programs help immigrants find new opportunities and integrate in a new society through building professional networks and finding jobs. The networking programmes support describing your current network and expertise, growing your network, and setting your personal goals. They share information about informal and formal local habits. Most importantly, they might create new possibilities and relationships that the international talent did not plan or see coming.

Networking is like planting seeds. With some preparation, care and time, it has the potential to grow into something fruitful. Networking is a practice that immigrants are encouraged to adopt so that they can find a good job and expand their circle of acquaintances. Stimulating, broadening and activating the professional network of jobseekers with a migration background creates awareness, job opportunities and sustainable employment.

References

Baker, W. (2000). Achieving success through social capital: Tapping the hidden resources in your personal and business networks. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Carayannis, E.G. and Campbell, D.F.J. (2009). “‘Mode 3’ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: toward a 21st-century fractal innovation ecosystem”. International Journal of Technology Management. 46 (3/4): 201–234. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374.

CareerLink (2015). Tips on how to access the hidden job market. Available at: https://careerlinkbc.wordpress.com/2015/03/02/tips-on-how-to-access-the-hidden-job-market/ Accessed on 17.5.2021.

Castells, M. (2004). The power of identity. The information age: economy, society and culture. Volume 2,2nd edn (Malden: Blackwell).

Castells, M. (2000). The rise of the network society. The information age: economy, society and culture. Volume 1, 2nd edn (Malden: Blackwell).

Coleman, J. (1988) “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital” American Journal of Sociology 94 Supplement: S95-S120.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches, CA: Thousand Oaks, Sage.

De Janasz, S.C. and Forret, M.L. (2008). Learning The Art of Networking: A Critical Skill for Enhancing Social Capital and Career Success. Journal of Management Education. 2008;32(5):629-650. Doi: 10.1177/1052562907307637

Garcia, E.V. (2016) Strategic planning: a tool for personal and career growth, Heart Asia 2016; 8: 36-39. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2015-010684

Gould, J. (2017). Career development: A plan for action. Nature 548, 489–490. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7668-489a

Johnson, D.W. and Johnson, F.P. (2009). Joining together: Group theory and group skills. 10. ed., Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ [u.a.].

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Locke E.A., Latham G.P. (2006). New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(5):265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

Marshall, C. and Rossman, G. (2011). Designing Qualitative Research, 5th edn, London: Sag

MESH (2021). Networking Coaching Guide. https://networking2work.weebly.com

Schöttle, A. and Tillmann, P.A. (2018). “Explaining the benefits of team goals to support collaboration. ”In: Proc. 26th Annual Conference of the International. Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), González, V.A. (ed.), Chennai, India, pp. 432–441. DOI: doi.org/10.24928/2018/0490. Available at: www.iglc.net Accessed on 12.2.2021.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

[1] Essi Hillgren is project advisor and project manager at Turku University of Applied Sciences. She has been running the MESH project, which aims to support international talents to find their way to Finnish working life by offering career mentoring and networking coaching.

[2] Janna Peltola is a project worker at Turku University of Applied Sciences. She has been part of the ESF-funded MESH project supporting and promoting possibilities of international talents in the Finnish labour markets via mentoring and networking.

[3] Fatih Yilmaz is a research fellow and project manager at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. He has been recently managing two ESF projects: All-in-one 4 HER and Super-mentor. His field of expertise covers migration and integration, as well as peace studies.

[4] Nasrin Jahan Jinia, PhD is a teacher and MESH project expert of the department of Well-being and Health Technology, Tampere University of Applied Sciences. Her field of expertise covers women’s empowerment, immigration governance and empowerment, Multi-culturalism, Networking, NGOs and Civil Society.

[5] Ulla-Maija Koivula was a principal teacher and a MESH project advisor at Tampere University of Applied Sciences. She was an experienced and respected expert in project work, multi-cultural work and social sciences. Ulla-Maija Koivula passed away in spring 2021 and a colleague Minna Niemi completed her writing work on this article.

[6] More information on MESH project is available at https://mesh.turkuamk.fi/in-english/

[7] Such as this one on the video: https://www.facebook.com/514048215317462/videos/623206201915716

[8] The platform can be reached by this link: https://all-in-one4her.eu

[9] HER Welcome Application can be reached at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=eu.allinone4her.her&hl=en_US&gl=US and https://apps.apple.com/th/app/her-welcome-app/id1570396001#?platform=iphone