The underlying source of a terrorist organization’s sustainability seems altruistic; it claims to be a champion of a larger cause. This claim to legitimacy underscores its raison d’etre and shapes its reputation. Terrorism is a theater where the battle for legitimacy is contested between the state and the terror group. As of May 2018, the Spanish State seems to have resolutely won that battle against the Basque separatist group ETA. ETA who stands for “Euskadi ta Askatasuna” or “Basque Homeland and Freedom” in the Basque language waved almost a five-decade terrorist campaign against the Spanish State. Having failed to achieve its goal of an independent Basque state in northern Spain and southern France, ETA announced complete dissolution on May 2, 2018. How has ETA come to the end of its existence? There are a few possible explanations, yet in the long run, the reason behind group’s dissolution appears to indicate that its violence hindered its claim to legitimacy, thus self-defeating the group and ending itself.

Sustaining the claim of acting on behalf of the people while operating underground in isolation from the masses and in the absence of popular support or a good reputation can pose difficult existential and ideological challenges for the terrorist organizations (Cronin, 2009). ETA’s early years had similar challenges as the organization grew out of Franco’s repressive regime. After the end of the civil war in Spain in 1939, General Franco severely punished the Basques who had allied with the Republicans during the war. His labeling of “the traitors” followed eradicating thousands and leaving many more to be perished under brutal working conditions in labor camps (Powell 2011). Therefore, Basques grievances against the Spanish government ran deep in which the roots of ETA’s legitimacy were entrenched, especially beginning with the Franco’s political repression. For an organization who initially appeared to have the necessary sources of legitimacy for representing the anger and frustration among Basques however, the popular support has eventually waned and the organization has gone through splintering, disagreements and even fratricide throughout its lifetime (Cronin, 2009).

There are several reasons behind ETA’s failure to achieve its objectives and to lose its popular support. First of all, most governments’ initial response to terrorism have been from a security/military perspective (Cronin, 2011), and Spain’s case was no different even after its transition into a democracy. The Spanish counterterrorism regime, especially following the cooperation of France and Spain’s transition into democracy, put existential pressures on ETA. The organization claimed its first victim in late 1960s. In response, Spanish security forces came down on the organization quite hard. Its militants went through imprisonment, torture, exile, and extrajudicial targeting which has come to be described as Spanish Dirty War. Secondly, one must acknowledge the non-military approaches that were eventually utilized by the Spanish State. For instance, Spain banned Basque Euzkadi ta Askatasuna (ETA) and its political wing Batasuna while keeping conciliatory measures and practices for “social reinsertion”. This gave an exit option to those involved in militancy to abandon insurgency in order to rejoin civil society. Such non-military measures including offering amnesty to the militants and opening negotiations helped diminish organization’s cohesion. Thirdly, Spain’s administrative concessions to its regions in terms of fiscal, institutional and legislative autonomy as well as the overall consolidation of Spanish democracy helped depreciate the terrorist group’s raison d’être. Above all however, the detrimental reason behind the group’s failure was its indiscriminate violence.

Terrorist organizations want their existence and struggle to be known widely, for which they use indiscriminate violence to instill fear and panic among large populations (Hoffman 2010). Terrorist violence is also a tool to provoke a disproportionate government response in the contest of legitimacy. Moreover, violence aims to keep the in-group cohesion and creates opportunities to challenge the state. Above all, violence shatters the norms of society and attracts the attention of masses. However, while attracting the mass attention is one goal, achieving the strategic organizational objectives is another. The nature and the intensity of violence may jeopardize the necessary elements for achieving policy objectives as this has been observed in the following cases.

Terrorist groups that set territorial objectives for themselves, such as ETA, have not turned out to be achieving those goals generally. For instance, Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) and the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA) have all similar strategic territorial goals; ending what they deemed to be foreign occupations. PKK’s ambitions of an independent Kurdish state were abandoned by the group itself after the decapitation of its leader; HUM has accomplished little in forming a Kashmiri state; and Irish unification is not on the horizon. ETA on the other hand may claim to have accomplished making progress in civil and political rights however, it has failed to achieve its main demand of a sovereign Basque state. Nevertheless, even when they fall short of achieving their objectives, terrorist groups still hold onto using violence which in turn becomes both a sustaining and a defeating factor for their existence. As such, in 1981 some ETA militants accepted an amnesty offer from the Spanish authorities at a time when the group was weakened, yet the violence persisted (Cronin, 2011). 44 members of the ETA who took on the amnesty offer were targeted by other recruits who accused them of betraying the movement. Their murders prompted public outrage among the Basque population, denting the organization’s legitimacy and its popular support.

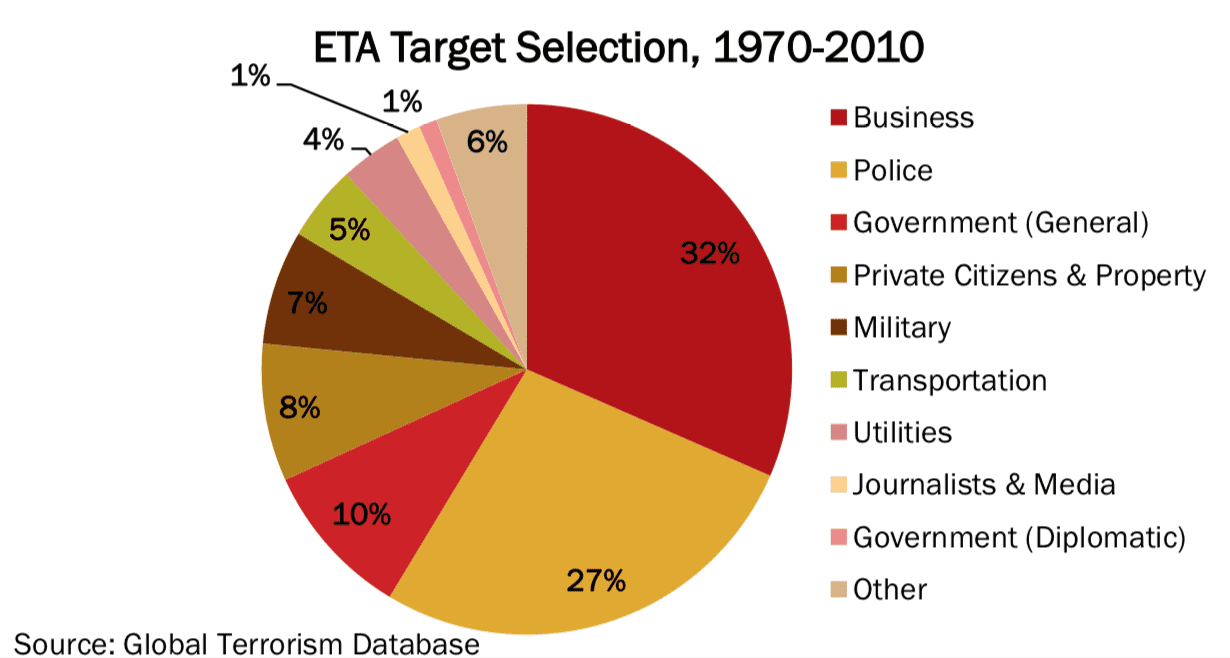

Terrorist groups, especially the nationalist-separatist ones such as ETA adopting territorial goals aim to capitalize on popular support by targeting symbolic targets and members of security forces. They aim to challenge government’s control over citizens and territory. This form of terrorism generally accompanies rural guerrilla warfare (Crenshaw, 2011).As such, ETA initially targeted mostly the symbols of the Spanish State, such as public infrastructure and the law enforcement. However, their targeting evolved to become increasingly indiscriminate and counterproductive to the cause. Between 1994 and 2004, 70 percent of the victims were civilians, and most were Basques (Maclean, 2004). This sort of violence was detrimental to the group’s reputation, especially for such a nationalist-separatist one. Civilian targeting in ETA’s case suggests that terrorism as an instrument of coercion is counterproductive, and its failure is inherent to the tactic of terrorism itself. Political scientist Max Abrahms makes the case that terror groups fail to win concessions by primarily attacking civilian targets. He delineates, “a change in targeting from military to civilian generates high positive odds for complete failure, and the likelihood of partial success or even near failure falls sharply” (Abrahms, 2012). In this regard, using violence and/or refusing to abandon it presents existential problems for these groups. Terrorism in this sense can be self-defeating.

Continuing on its history, attacks such as the 1987 car bomb at a Barcelona supermarket which killed 21 civilians and injured 45, including a pregnant woman and two children, drew popular revulsion and international outrage against the organization. Another haunting moment was in 1997 when the murder of a conservative councilor garnered a national outrage. The Economist report from Madrid on Jul 17th 1997 reads the following: “The response was overwhelming. People took to the streets in protest all over Spain, half a million in Madrid alone. In the Basque country, where it mattered most, protest turned to violence. There were attacks on offices belonging to Herri Batasuna, ETA’s political wing. In several places relatives of ETA members expressed their horror. Even Basques who had previously found it hard to condemn the organization had at last, it seemed, had enough.” (The Economist, 1997). In ETA’s case, violence, which increasingly targeted civilians mostly in urban areas, caused ETA’s legitimacy and reputation to take irredeemable damage, eventually leading to organization’s demise.

In conclusion, one of the deadliest terror groups in Western Europe, has self-defeated its cause. The mistreatment of Basque nationalists, especially during the Spain’s repressive State of Exception (1961-1975) period, meant support for the organization as a legitimate champion. However, Spain’s transition to democracy, stable military counterterrorism efforts including the global post-2001 counterterror regime and non-military responses such as opening up negotiations and social reinsertion policies all worked against ETA. Under these circumstances, increasing indiscriminate violence, let alone the refusal to abandon it, meant waning popular support and losing the battle of legitimacy. State actors, both Spain and France, undermined ETA’s ability to wage an armed struggle. The organization had eventually declared a “definitive end” to its armed campaign in 2011 and effectively dissolved as of May 2018. Is bad publicity better than no publicity in so far as some terrorist groups are concerned? In the end, the Basque case indicates that for groups like ETA the answer is negative.

Bibliography

Abrahms, Max. 2012. “The Political Effectiveness of Terrorism Revisited.” Comparative Political Studies 45(3): 366–93.

Crenshaw, Martha. 2011. Explaining terrorism: causes, processes, and consequences.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. 2009. How terrorism ends: Understanding the decline and demise of terrorist campaigns. Princeton University Press.

Hoffman, Bruce. 2010. “A Diverse and More Complex Threat.” The National Interest.

Powell, Robert. 2011. International Terrorism: The Global War on Terror. Madacy (Music Distributor).

Renwick Maclean. 2004. “Madrid Sees Signs of ETA’s Death Throes,” International Herald Tribune, December 20, 2004, accessed at http://www.iht.com/articles/ 2004/12/20/basque_ed3_.php

The Economist, “A murder too far”, Jul 17th 1997, The Print Edition, Madrid, Spain. Accessed at https://www.economist.com/node/151703

Source of the graph, see: https://www.start.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/publications/br/ETACeasefires.pdf