1. Introduction

We need to discuss what war is, whether there are certain fundamentals of war that do not change through time and circumstances—namely the nature of war—or whether war has been changing. Our understanding of war’s nature inherently influences how we approach the conduct of war, how we develop military strategy, doctrine and concepts, and train and equip combat forces.[1] Every state has a policy goal, and it has to have an understanding about war and the conduct of war to ensure its security. Yet, policy should not ask the armed forces to engage in actions or activities which are not consistent with their capabilities or with the true nature of war.[2] While war—or the threat of war—has always been one of the most powerful influences that has shaped the course of international relations, there have been relatively fewer studies about war and warfare in the international relations domain. Considering the current lack of knowledge about war and security matters,[3] at the risk of adopting flawed concepts, it becomes important to understand the fundamental themes about war, policy and strategy before discussing and evaluating any emerging concept. This article aims to present the fundamental knowledge about the nature of war and strategy. While the initial sections about war, policy and the nature of war will be mainly based on Clausewitz’s work, the following sections will be based on modern interpretations of strategy, grand strategy and strategic theory.

2. War and Policy

Clausewitz states, “war is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means.”[4] This sentence may be the most quoted passage of Clausewitz’s work which represents “the primacy of policy” and is usually regarded as his core message. There are numerous other passages where he has emphasized the primacy of policy such as: “the political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose,” or “war should never be thought of as something autonomous but always as an instrument of policy” and “policy, then, will permeate all military operations and have a continuous influence on them.”[5]

However, the primacy of the policy should not be understood as political determinism. While “political purpose remains the supreme consideration,” it is “not a tyrant. It must adapt itself to its chosen means.” Policy permeates all military operations; however, it does “as far as their violent nature will admit.” Clausewitz’ statement “war has its own grammar, but not its own logic,”[6] can be understood as the summary of the relationship between war and policy. War has its own restrictions as grammar does on speech, but this does not change the fact that it is merely a political instrument.

The scale of the political objective determines the scope of the military aim. However, another factor which determines the military aim is the enemy’s response. In the very beginning of On War, Clausewitz begins by going straight to the heart of the matter and states:

War is nothing but a duel on a larger scale. Countless duels go to make up war, but a picture of it as a whole can be formed by imagining a pair of wrestlers. Each tries through physical force to compel the other to do his will; his immediate aim is to throw his opponent in order to make him incapable of further resistance. War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.[7]

The enemy’s role is at the centre as it captures the essence of war, simply because war is a bilateral use of violence rather than a unilateral use; violence met by violence. The fact that “war is a duel” has a number of impacts on the entire theory of war. For instance, the military objective of the war may vary depending on the type of war. In an unlimited war, as in the Second World War, a military objective might be rendering the enemy totally defenceless while in a limited war a military objective can be coercing the enemy to affect his will.

Once the interaction begins, both sides start a series of activities to make a judgement about enemy’s character, their institutions, and general situation, and this can only made by using the laws of probability in the real world.[8] Because of the imperfect knowledge of the situation, and usually unreliable intelligence, any given situation requires that probabilities be calculated in light of the circumstances. This is why, “no other human activity [other than war] is so continuously or universally bound up with chance.” Through the element of chance, guesswork and luck come to play a great part in war.[9] Chance, together with danger and courage, from the very start requires the interplay of probabilities and possibilities. As Clausewitz noted, “so-called mathematical factors never find a firm basis in military calculations. In the whole range of human activities, war most closely resembles a game of cards.”[10] [emphasis added]

All of these may sound banal, but it is crucial to know that history is replete with cases where actors underestimated the strength of their opponents, worse, they did not even take their opponents into consideration before they embarked on their military operation. The US’s “War against Global Terrorism” may represent a good example of an actor who does not pay attention to their enemy and the dire consequences. Clausewitz’s idea that escalation was not determined by the laws of necessity, but by the laws of probability, was also truly a revolutionary one in the military theory of Clausewitz’s day.[11]

3. The Nature versus Character of War

According to Clausewitz, war has two natures: objective and subjective. The objective nature of war represents those qualities common to all warfare in all periods.”[12] On War is a quest for objective knowledge, namely, the universal and eternal nature of war. On the contrary, the subjective nature of war corresponds to the actual, dynamically changeable, highly variable detail of historical warfare, as it is valid only for a specific time and place. Military forces, their doctrines, and the weapons that are used in each war are examples of this subjective nature. In today’s language, the objective nature of war is called “the nature of war” while the subjective nature of war is called “the character of war.”[13]

So, what is the nature of war? What are the common features of all warfare in all periods? If we are to follow Clausewitz, all wars are driven by unstable relations among three forces: “passion and enmity,” “chance and creativity” and “policy reason.” He wrote:

War is more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case. As a total phenomenon its dominant tendencies always make war a paradoxical trinity–composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to reason alone.[14] [emphasis added]

According to Clausewitz, these three tendencies are present in every war and yet vary in their relationship to one another. He maintains, “Our task therefore is to develop a theory that maintains a balance between these three tendencies, like an object suspended between three magnets.” The weight of each tendency depends on the context of each war. More importantly, the remarkable trinity demonstrates that war’s nature is inseparable from the historical and socio-political contexts in which that war arises, so therefore, war cannot be examined in isolation as a thing-in-itself.[15]

He attributes objective (unchanging) tendencies to subjective ones (ever-changing): namely, he attributes passion and enmity to the “people,” chance and probability to “the commander and army,” and political reason to the “government.” However, this should not be understood as a rigid, inflexible, and mutually exclusive relationship, as he does not equate them exactly. “The government” in this case stands for any ruling body; any “agglomeration of loosely associated forces;” the military represents any warring body in any era, while the “populace” suggests the population/citizenry of any society or culture in any period of history.[16] For example, policy may be the responsibility of the government, but in the modern world it is likely to be influenced by a public opinion that could prove volatile. Additionally, policy can be influenced by those military commanders who are shaping strategy, in a process of dialogue with politicians.

Danger, physical exertion, uncertainty and chance are four elements comprise the “climate of war” that is common to all wars.[17] They can also be grouped into a single concept of general friction, which is one of the unique concepts invented by Clausewitz. Friction can be described as “the factors that distinguish real war from war on paper.” Clausewitz states “Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and produce a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war.” In theory, everything may seem reasonable and flawless, however in practice; every individual has the potential to cause problems. Danger and physical exertion can aggravate any problems to such an extent that they must be ranked among its principal causes.[18]

In summary, the nature of war rests on the fundamental cause–effect relationships involving the forces of purpose, chance, and hostility. These principal elements, though always present, were constantly in flux, both influencing and influenced by one another. The interaction of these forces occurs in an atmosphere of war where danger, physical extortion, chance, uncertainty and friction reigns. All wars, whether major or limited, are instrument for political goals. Before moving on to the strategy, which is mainly about the essentials of achieving those political goals, following section will discuss recent alternative.

4. Alternative Approaches to Clausewitzian War

The trinity constitutes the heart of Clausewitz’s theory, but it has been the most targeted by other academics and experts as well. Following the end of the Cold War, certain scholars claimed that Clausewitz’s trinitarian war is the product of his own time and is now obsolete. His world picture, which is premised upon governments, armies and nations, is outdated. According to Martin Van Creveld, we now live in a post-Clausewitzian era wherein war is no longer conducted solely by governments with armies on behalf of their societies. Instead, the state as understood by Clausewitz is in decline and contemporary warfare is instead being waged by non-state actors often for non-political purposes.[19] According to Van Creveld, if low intensity conflict is indeed the wave of the future, then strategy in its classical sense will disappear.[20] John Keegan objected to Clausewitz’s famous dictum, and at the beginning of his seminal book “A History of Warfare” penned that: “war is not the continuation of politics by other means.” Instead, according to Keegan, the conduct of war was “culturally determined,” and the sort of war which Clausewitz was describing belonged to a short period of history and to a limited part of the globe.[21] For Mary Kaldor, like for Martin van Creveld, new wars were “irregular,” being fought for economic as well as political purposes. These wars were usually waged by warlords not only for policy but also for economic reasons, which is why armed conflict is sustained by the warlords.[22] All three authors believe that the current notion of the state is not the same as what Clausewitz described in his own era and wars are being fought between states and non-state actors as opposed to the state-on-state wars of Clausewitz’s time. Thus, in the words of van Creveld, future wars will be “non-trinitarian.”

Furthermore, the proponents of fourth generation warfare (4GW) also based their concept on the notion of “non-trinitarian” war and presumed that future wars will increasingly be waged outside the nation-state framework.[23] According to this concept, “war has entered a new generation. It is not the high-technology war but rather an evolved form of insurgency which uses all available networks to convince the enemy’s political decision-makers. 4GW does not attempt to win by defeating the enemy’s military forces. Instead, combining guerrilla tactics or civil disobedience with the soft networks of social, cultural and economic ties, disinformation campaigns and innovative political activity, it directly attacks the will of enemy decision-makers. Therefore, decisive Napoleonic battles and wide-ranging high-speed manoeuvre campaigns are irrelevant to 4GW.”[24]

Clausewitzian scholars have argued that the notion of non-trinitarian war is simply the result of a misinterpretation of Clausewitz’s trinity. The proponents of non-trinitarian war identify the “people, army, and government” as being the primary trinity, while according to Clausewitzian scholars, they are merely representations of the actual tendencies of “passion, reason and the play of chance.” These forces or tendencies are universal, and we find them at play in every war, even including in the war on terror, which van Creveld refers to as “non-trinitarian.” [25] To reduce Clausewitz’s trinity to an allegedly obsolete social paradigm of “people, army and government” in an attempt to marginalize Clausewitzian theory is not valid nor is it useful.[26] According to this understanding, even organizations that are motivated by religion today, such as Hezbollah, Taliban or ISIL, organize themselves around certain policy goals and strategies that are developed to achieve those policy goals, and they frequently use religion as a tool. In other words, the impact of religion on their activities is indisputable; however, this does not negate the fact that they develop policies and strategies to achieve their purposes.

5. Strategic Theory, Strategy and Grand Strategy

Strategy is one word that is so widely used but hardly understood. While it was borne out of politics, it has become popular in other fields as well, including economics and management. The term has acquired such universality that it has been robbed of meaning.[27] Policy and strategy, despite their vital importance to the security of any nation, are not well understood and these two terms are widely conflated by officials, even by those in key governmental positions.[28] Clausewitz provides a brilliant and very concise, albeit narrow, definition: “strategy is the use of the engagements for the purpose of the war.”[29] Sir Basil Liddell Hart defined strategy as: “the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfil the ends of policy.”[30] Contemporary strategic theorist Colin S. Gray defines strategy as “the direction and use made of force and the threat of force for the purposes of policy as decided by politics.” [31] For Wylie, strategy is “a plan of action designed in order to achieve some end: a purpose together with a system of measures for its accomplishment.”[32] Beatrice Heuser makes a similar definition with an emphasis on the enemy’s will: “Strategy is a comprehensive way to try to pursue political ends, including the threat or actual use of force, in a dialectic of wills.”[33] It is obvious that strategy is closely related to the conduct of war. This is why, not surprisingly the terms “strategy” and “art or conduct of war” have been nearly synonymous at times.[34] Although there are other definitions worth being discussed here, to keep it short, strategy can be summarized as the use of ways and means to achieve the desired ends, and functions as a link between policy and the military. What is common in all definitions is its function of instrumentality.

When it comes to grand strategy, it is defined as the direction of many or all of the assets of a security community, including its military instrument, for the purposes of policy goals. In a sense, it can be considered as a synonym for “statecraft.”[35] Grand strategy identifies and articulates how a political actor’s security objectives will be achieved using a combination of instruments of power—including military, diplomatic, and economic instruments.[36] Posen describes it as “a political-military, means-end chain, a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.”[37] Gaddis defines grand strategy as “the calculated relationship of means to large ends.”[38] As one can easily discern, while strategy is more related to the conduct of military tools, grand strategy comprises all national power tools. This is why strategy is frequently called “military strategy” instead of merely strategy, supposedly to separate it from grand strategy. Echevarria notes that military strategy refers to the “concern of the general” while grand strategy can be thought of as the “concern of the head of state” of which the general’s business is but one aspect.[39] Ideally, a military strategy should be formulated within the parameters established by a grand strategy because a security community cannot design and execute a strictly military-based strategy. Every military activity—whether it is a total war or a limited conflict—has political‐diplomatic, social‐cultural, and economic, inter alia, aspects to the war.[40]

As for strategic theory, it amounts to an entire framework of concepts and principles regarding strategy and grand strategy. Strategic theory postulates that all wars in history share certain characteristics in common. It is a system of interlocking concepts and principles pertaining to strategy and grand strategy, which postulates that a system of attributes common to all wars exists and that war belongs to a larger body of human relations and actions known as politics.[41] It provides guidance on how to manage the complexities of using force to achieve policy ends[42] and comprises thoughts about making effective strategy.[43] Since it is not linked to a particular historical context, strategic theory allows the strategist to extricate himself from situational bias.[44] For these reasons, it may serve as a “basis of valuation” in understanding the validity and soundness of emerging concepts. However, one should be cautious because strategic theory is too comprehensive to grasp all at once as it deals with intricate phenomena such as war, policy and strategy. As Frans P.B. Osinga noted, “it is a strange animal indeed,” which deviates from “proper” scientific theory. It rather belongs to the domain of social science, in which parsimony is only occasionally appropriate.[45]

As mentioned above, in theory, military strategy cannot be rendered alone. It should be nested in a broader framework, where other dimensions such as the diplomatic, economic and social dimensions are taken into consideration. However, in practice, there might be cases where military strategy drives grand strategy and operates independently. For instance, as in the case of Napoleon or Hitler, this occurs when military and grand strategy is embodied in the same person. At other times, grand strategy might be dominant and prevents military strategy from being carried out effectively.[46] This is reminiscent of General Wesley Clark’s—Supreme Allied Commander of NATO during the Kosovo War— eye-catching story about when he first heard about the US decision to go to war against Iraq. General Clark explains how he learned of the decision from one of his ex-colleagues who used to work in the US Department of Defence and illustrates how the US military was isolated from the decision-making process when the US government ultimately made the decision to go to war against Iraq.[47]

Before proceeding further, it is important to note that strategy, and hence strategic theory, is an attempt to explain what has already been practiced throughout history. It is a depiction of the universal and eternal features of strategy-making. Strategy, as a term we would understand today, was first utilized in the 1770s,[48] however, as Gray noted, the basic logic of strategy can be found in all places and periods of human history, regardless of which term was used by distinct societies or cultures. Strategy is unavoidable because humans, the common denominator between the past and the future, always need security and it is in their nature to behave politically and strategically against potential dangers.[49] The human need for security requires political activity, and that activity generates the need for strategy. The interdependencies of security, politics, and strategy render strategic theory both necessary and possible.[50] As Johnson noted, despite enormous advances in technology, it seems clear that decisions will still be made some humans and strategic planners will continue to make decisions on perennial problems such as how one may convert operational success into a strategic advantage. The fundamentals in the conduct of war are unchanged.[51]

Military strategy is usually expressed by the magic formula proposed by the retired U.S. Army Colonel Arthur Lykke. It consists of three simple aspects; policy ends, strategic ways, and military means (EWM), where policy end denotes the goals we aspire to achieve, strategic ways correspond to the alternative courses of action to follow, and military means are the resources that we could employ. Ends, Ways and Means logic can be used at all levels of decision-making, from the tactical level all the way up to grand strategy.[52] Built on the Clausewitzian definition of strategy, Lykke’s formula is an excellent construct to explain the essence of strategy in a concise manner. However, it is also a mechanistic explanation which is far from reflecting the true nature of strategy where complexity, dynamism, uncertainty and chaos reign.[53] It is not that we should not use the construct, but we should know that there is much more to strategy than this formula.

The strategic level where strategy is developed and directed corresponds to one level of war. For this reason, it is more helpful to examine strategy in relation to other “levels of war,” namely the political, operational and tactical levels, for a deeper grasp of its function and its meaning.

5.1 Levels of War and Strategy

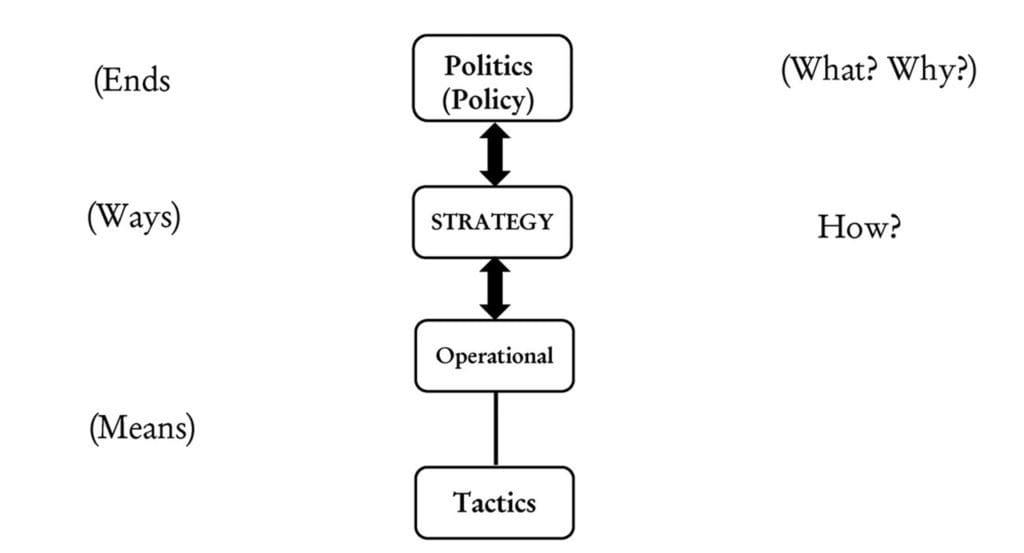

There are four levels of war adopted by most armies: namely policy, strategy, operations and tactics. Traditionally, the construct has been discerned as three levels, but a fourth level was added with the introduction of the operational level in the 1980s. In theory, politics produces policy. Strategy connects policy with military assets, which means that strategy determines military forces and their tasks that can lead to the achievement of the desired aims of policy. The operational and tactical levels execute those concrete tasks decided by the strategy (Figure 2-1). The levels are different in nature and they answer different questions. Policy answers to the question of “why and what,” while strategy seeks an answer for “how,” and tactics do so.

The main challenge in strategy is to convert military power into political effect. “A good strategy” is expected to be one in which all three components are tuned, that is, the means are sufficient to accomplish the ends through the designated ways.[54] It is extremely difficult because there is no natural harmony between levels[55] and it requires an exceptional talent to determine which actions match which policy ends. This is what strategy does—it fills the gap between political goals and military activity and ensures all levels function properly. Despite the huge advances in technology, there is no scientific method to determine how much military power—or other instruments—is/are enough or when this balance has been achieved. It is more of an art than a science,[56] and success largely depends on strategic sense and judgement.[57] Strategy is highly difficult to execute because warfare is inherently complex. It is “a function of interconnected variables”[58] whose weights differ in each context. Apart from its sheer complexity, ‘the friction’ and the presence of an ‘independent enemy’ are two leading factors that contribute to this difficulty.

Figure 2‑1 Levels of War and Strategy

Gray employs a bridge metaphor to explain the instrumentality function of the strategy. A bridge must operate in both ways; therefore, the strategist needs not just to translate policy intentions into operations but also to adjust policy in light of operations.[59] This is done through negotiation; the strategies are developed in an ongoing process of negotiation among potential stakeholders, through a civilian-military partnership. Usually it consists of a committee-driven process, but it is always led by the characters of key leaders and strategic inspiration is usually a product of a single person, not a committee. However, this person, no matter what if they are a genius, needs a staff and confident subordinate commanders to translate their ideas into actionable plans.[60]

It is important to discern that the strategy is not simply the application of force itself. The forces of all levels are designed to achieve strategic effect, but strategy can only be practiced tactically. All strategy has to be done via tactics, and all tactical effort has some strategic effect.[61] Significant strategic impact results from the cumulative effect of numerous tactical events while sometimes a small tactical unit can cause more significant consequences than major forces.[62] A special forces team, a tactical level unit, performing behind enemy lines can play a more significant role strategically than a division or corps, an operational level unit, carrying out a conventional front attack. Therefore, the strategic meaning of action is not contained in the behaviour itself, but instead by the context in which it occurs.[63] While the action itself is tactical—or operational—by definition, it is only strategic in ultimate meaning for the entire conflict. Strategy is all about the consequences of tactical behaviours.

Despite their differences, all levels constitute a unity. If one level is absent, or not functioning well, it jeopardises the entire project. When political guidance is weak or missing, the strategists cannot be sure of the end-state to which they should lead their tactical enablers. If a strategy is weak or absent despite the existence of adequate political guidance, tactical forces might prosecute an unjust war, however they are excellent in their fighting capabilities as there is not necessarily a “bridge” converting political goals to actions. If there is no competent tactical ability, political and strategic endeavour becomes worthless, so they do not exist.

Strategy summarized here represents the narrower understanding, which takes military resources as the main instrument to achieve policy goals. The following section will discuss the grand strategy, which has evolved from this narrow meaning of strategy since the beginning of the twentieth century.

5.2 Grand Strategy

As Hew Strachan indicated, there has been an evolution in the meaning of the term “strategy” since it was first conceptualized by classical theorists such as Clausewitz and Jomini. By 1900, strategy had been used to explain anything concerning the actions of generals in the conduct of operations in a particular theatre.[64] It usually referred to a relationship below the level of politics, between strategy and tactics. But following the experience of two World Wars, where all national resources were used, alongside the Cold War, during which deterrence became the essence of strategy, the function of strategy shifted to higher levels. The operational level, which became effective in the 1980s, took the place of what classical theorists called strategy, whereas strategy in practice became something between strategy and policy. In fact, strategy has even begun to be used as a synonym for policy.[65]

In the nineteenth century, grand strategy was not a well-anchored concept, but certainly had currency. Of all the early authors mentioning grand strategy, it was General William Tecumseh Sherman who may have been most interested in contextualizing the term. However, Julian Corbett was the first to use grand strategy in a manner which is identifiably modern.[66] In 1911, Corbett, addressing the officers at the Royal Naval War College, stated; “major strategy in its broadest sense has to deal with the whole resources of the nation for war. It is a branch of statesmanship.”[67] Distinguishing between ‘major strategy’ and ‘minor strategy,’ Corbett was actually drawing our attention to a greater strategy which postulates keeping an eye on all the resources of a nation while conducting military strategy during a war. Following the First World War, further scholars such as J.C. Fuller, Liddell Hart, Edward Mead Earle and André Beaufre brought forward other, non-military aspects in strategy. With a notion similar to Corbett’s major strategy, in 1923, Fuller introduced the term “grand strategy” and claimed that strategy is not only a war-time business. According to Fuller, how a nation fights in a war largely depends on the preparation that it has conducted in peace time. Highly impressed by Fuller’s ideas, Liddell Hart further developed and advocated the concept of grand strategy. Interestingly, although the concept had been discussed before Liddell Hart, it is generally assumed that no concept of grand strategy existed prior to his discussion of it in 1929.[68] Liddell Hart interpreted that grand strategy is “practically synonymous with the policy which governs the conduct of war” and it serves to bring out the sense of “policy in execution.”[69]

Another theorist highlighted together with Liddell Hart in the literature was American wartime theorist Edward Mead Earle. In his famous book, Makers of Modern Strategy (1943), he emphasized that strategy is an inherent element of statecraft at all times, both in war and peace.

But as war and society have become more complicated – and war … is an inherent part of society – strategy has of necessity required increasing consideration of non-military factors, economic, psychological, moral, political, and technological. Strategy, therefore, is not merely a concept of wartime, but is an inherent element of statecraft at all times … In the present-day world, then, strategy is the art of controlling and utilizing the resources of a nation – or a coalition of nations –including its armed forces, to the end that its vital interests shall be effectively promoted and secured against enemies, actual, potential, or merely presumed.[70]

Writing in the middle of the Second World War, Earle indicated the importance of non-military factors and implied that strategy inevitably must be rendered as grand strategy. Two World Wars demonstrated that the conduct of war involves more than a military strategy, there are political, social or economic dimensions to war as well. Similarly, André Beaufre also argued that all warfare is ‘total,’ and is carried on in all fields of action, political, economic, military, cultural, and so forth.[71] In the same vein, modern strategic theorist Colin S. Gray postulates that strategy indispensably has to be grand.

All strategy is grand strategy. Military strategies must be nested in a more inclusive framework, if only in order to lighten the burden of support for policy they are required to bear. A security community cannot design and execute a strictly military strategy. No matter the character of a conflict, be it a total war for survival or a contest for limited stakes, even if military activity by far is the most prominent of official behaviours, there must still be political‐diplomatic, social‐cultural, and economic, inter alia, aspects to the war (…)Whether or not a state or other security community designs a grand strategy explicitly, all of its assets will be in play in a conflict. The only difference between having and not having an explicit grand strategy, lies in the degree of cohesion among official behaviours and, naturally as a consequence of poor cohesion, in the likelihood of success.[72]

As Gray eloquently stated, whether it is a limited conflict or a major war, all conflicts inherently include non-military dimensions. In a limited war, a smaller number of dimensions can be in play whereas in a major war, almost all of a nation’s resources and powers are mobilized. Moreover, there might be cases where the military plays no part. Only the threat of force, instead of the direct use of force, can sometimes provide the desired effects. But whether it is the leading component or not, the military is indispensable in designing and executing grand strategy. Another important aspect that Gray draws our attention to is the fact that the notion of grand strategy functions whether we are aware of this fact or not. However, consciousness obviously increases the likelihood of success.

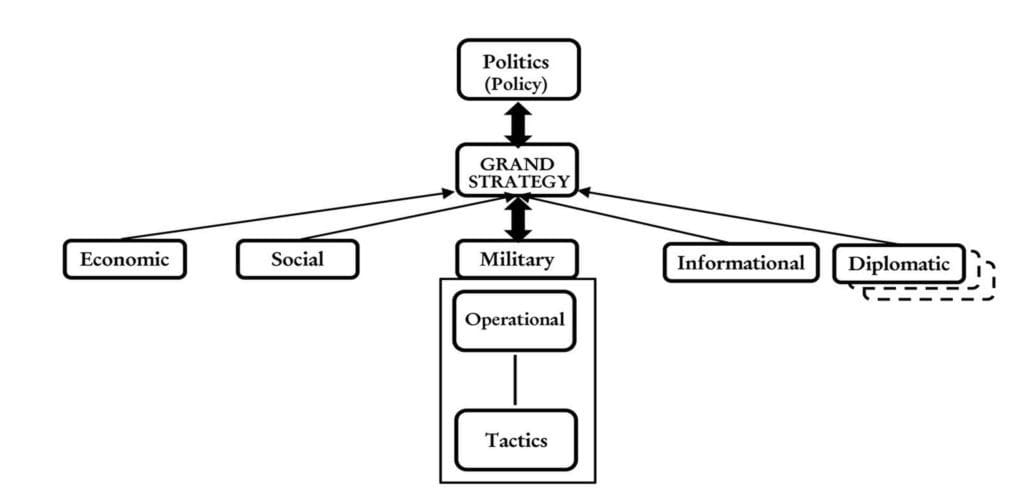

Against this background, Figure 2-2 represents a simple depiction of how grand strategy works. While military strategy forms a bridge between policy and the military, and it is concerned with the use of military forces for the purpose of war, grand strategy aims to determine the best possible combination of various dimensions including the military.

Figure 2‑2 Grand Strategy

Lonsdale & Kane grouped the instruments of grand strategy into four categories: military, diplomacy, intelligence and economy.[73] The “intelligence” can be replaced by “informational”, which is a broader aspect that includes propaganda and information warfare as well. Furthermore, the “social” dimension is too broad to be included under any other category, and therefore needs to be separated. Although these categories are the aspects most relevant to national security, the process of strategy/grand strategy-making is so complex that there might be other instruments which are not foreseen depending on the context and the characteristics of the state. The dotted boxes in Figure 2-2 refer to this fact.

5.3 Key Factors of Strategy-Making

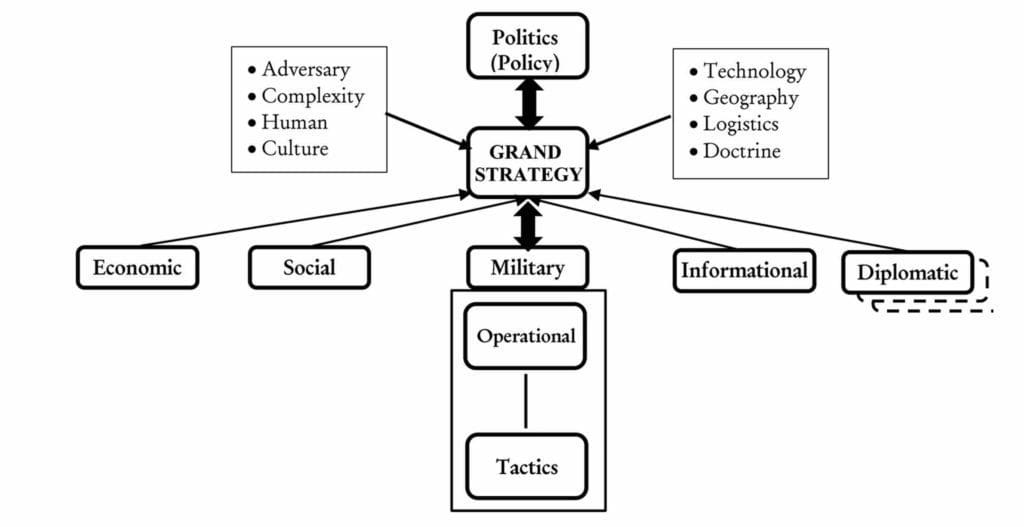

Figure 2‑3 Grand Strategy and Key Features

Besides the non-military dimensions, in each war, there are certain factors that need to be taken into the consideration in strategy-making. Arguably, there are eight dimensions in strategic theory, namely adversary, complexity, human, culture, technology, geography, logistics and doctrine, which are valid for all wars, whereas their relative weights depend on the context of the specific war in question. Each dimension plays its part with ever-changing importance in every conflict. (Figure 2-3)

6. Strategy in Context

While the main principles of strategic theory explained above applies all times and places, one should understand that strategies in a particular time is commanded significantly by its context. Colin S. Gray makes a distinciton between general theory of strategy and historically specific strategies. He states that “strategy in real‐world specificity derives from, and is shaped by and for, no fewer than the seven distinctive context: political, social‐cultural, economic, technological, military‐strategic, geopolitical and geostrategic, and historical” and general theory of strategy tries to ensure that none of these contexts is neglected in making strategy.[74]

However, the context is not only important for specific strategies drafted but also for the military theory developed in a certain period. Frans Osinga argues that understanding the strategist’s sources of influence helps understanding his theory because strategic theorists are influenced by both intellectual and social factors, both internal as well as external to the discipline. Referring to Avi Kober’s work[75], he presents following formative factors that shape and explain the development of a certain theory of conflict in a particular period, in a particular country or by a specific author: 1) the nature of war during successive periods; 2) the specific strategic circumstances of the countries involved; 3) the personal and professional experience of the particular thinker; 4) the intellectual and cultural climate of the period in question.[76]

This means that any theory cannot be understood without formative factors that create that specific theory. For instance, Azar Gat attributes the difficulties interpreting in Clausewitz to the fact that On War is a classic case where the text cannot be understood without its context; not only the military and intellectual context but also that provided by the evolution of Clausewitz’s own thought. Although he defines Clausewitz’ work as “a unique achievement that has never been equalled, the most sophisticated formulation of the theory of war, based on a highly stimulating intellectual paradigm, and brought the conception of military theory into line with the forefront of the general theoretical outlook of his time”, he argues, “reading On War as it stands, without the necessary preliminary knowledge is bound to result in misunderstanding.”[77] As Osinga expounded, it is difficult to understand Clausewitz’ theory without knowing the total war concept, which was initiated by the French Revolution and continued during the Napoleonic wars, the Prussian geo-strategic situation of the time, his personal experince in the Napoleonic wars or the impact of the Enlightment and Romantic Period.[78]

7. Strategy as a Whole

None of the aspects mentioned above, whether the ends-ways-means construct or its key features, can be ruled out in the conduct of war or strategy. War and strategy are interactively complex systems, a nonlinear phenomenon, where all these factors are in flux and play their own role. Technology has a huge impact on war, yet human, ethics, geography and logistics have an impact as well. It is so complex in its working parts that it is not possible to approach war through solely one or two perspectives. Clausewitz stated, “In war, more than in any other subject we must begin by looking at the nature of the whole; for here more than elsewhere the part and the whole must always be thought of together.”[79] There is no scientific formula to calculate the exact share of each factor. As Paul Van Viper indicated, it is useless to approach war with linear methods as the Americans do. [80]

All of the key factors explained above are valid for all wars. Strategists—and/or commanders—articulate a different combination of these factors in each war. As Heuser suggested, war is “a function of interconnected variables” [81] whose weights differ according to the context and circumstances. As the purpose and the intensity of the warfare could vary from one war to the next, or even multiple times within the same war, these factors are dynamic, influencing the outcome of war but also being influenced by one another. Strategy must be considered as a whole, and an effective strategy requires careful analysis including a weighing of the options where a number of variables must be considered to decide whether tactical deeds can be converted into political capital, in a continuously fluid and context-dependent environment. Echevarria’s weather metaphor is simple, yet concisely explains the logic:

To be sure, Clausewitz believed all wars were things of the same nature. However, that nature was, like the nature of the weather, dynamic, and its principal elements, even if always present, were constantly in flux. Like war, the weather consists of a few common and inescapable elements, such as barometric pressure, heat index, dew point, wind velocity, and so on. Nevertheless, the difference between a brief summer shower and a hurricane is significant, so much so, in fact, that we prepare for each quite differently. Indeed, the difference in degree is so great, the danger to our lives and property so much higher in the latter, that we might do well to consider showers and hurricanes different in kind, though both are certainly stormy weather. We might apply some of the same rules of thumb for each kind of weather, but also many different ones. [82]

This article explained the principal elements of war that we need to take into consideration in each war. They have different values in each type of warfare as the principal elements of weather have different values in each type of weather. These principal elements are crucial to understanding the nature of weather and to measuring their impact on the weather. The same rule applies to war as well. However, there is one important difference between the two. While it is possible to measure principal elements of the weather scientifically, this is not possible in the case of warfare.

Contact murat.caliskan@uclouvain.be, muratcaliskan78@gmail.com ESPO, Louvain Political Science Institute (SPLE), Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain La Neuve, Belgium

[1] Antulio J. Echevarria, Clausewitz and Contemporary War, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 58.

[2] Hew Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 77.

[3] Colin S. Gray, War, Peace and International Relations: An Introduction to Strategic Theory (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 23. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203088999.

[4] Carl Von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 87, 605.

[5] Ibid, pp. 87-88.

[6] Ibid, pp. 87-88, 605.

[7] Ibid, p. 75.

[8] Ibid, p. 80.

[9] Ibid, p. 85.

[10] Ibid, p. 86.

[11] Echevarria, Clausewitz and Contemporary War, p. 66.

[12] Clausewitz, On War, p.606.

[13] Gray, War, Peace and International Relations, p. 23.

[14] Clausewitz, On War, p. 89.

[15] Antulio J. Echevarria, Globalization and the Nature of War (Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S.A.W.C., 2003), p. 9.

[16] Echevarria Ibid, p. 10.

[17] Clausewitz, On War, p. 104.

[18] Ibid, p. 119.

[19] Martin Van Creveld, Transformation of War (New York: The Free Press, 1991), pp. 33-62.

[20] Ibid, p. 207.

[21] John Keegan, A History of Warfare (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), p.3.

[22] Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars, Third Edit (Polity Press, 2012).

[23] Antulio J. Echevarria, ‘Deconstructing the Theory of Fourth-Generation War’, Contemporary Security Policy 26, no. 2 (4 August 2005): p. 235, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260500211066.

[24] Thomas X. Hammes, ‘War Evolves into the Fourth Generation’, Contemporary Security Policy 26, no. 2 (4 August 2005): pp. 205-206, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260500190500.

[25] Echevarria, ‘Deconstructing the Theory of Fourth-Generation War’, p. 235; Hew Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 48-49; Gray, War, Peace and International Relations: An Introduction to Strategic Theory, p. 227; Lukas Milevski, ‘The Nature of Strategy versus the Character of War’, Comparative Strategy 35, no. 5 (19 October 2016): 438–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2016.1241007.

[26] Christopher Bassford and Edward J. Villacres, ‘Reclaiming the Clausewitzian Trinity’, accessed 2 May 2020, https://www.clausewitz.com/readings/Bassford/Trinity/TRININTR.htm#top.

[27] Hew Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 27.

[28] Paul Van Riper, ‘From Grand Strategy to Operational Design: Getting It Right’, Infinity Journal 4, no. 2 (2014): pp. 13–18.

[29] Carl Von Clausewitz, On War (New Jersey: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 132.

[30] Basil Henry Liddell Hart, The Strategy of Indirect Approach (London: Faber, 1946), p. 187.

|[31] Colin S. Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 29 doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579662.001.0001.

[32]. Joseph Caldwell Wylie, Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1967), p. 59.

[33] Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy, pp. 27-28.

[34] Antulio J. Echevarria, Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. (New York: Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition., 2017), p.3.

[35] Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice, p. 18.

[36] Tami Davis Biddle, ‘Strategy and Grand Strategy: What Students and Practitioners Need To Know’, U.S. Army War College Press, no. December (2015): 1–97.

[37] Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine France, Britain, and Germany between the World Wars (New York: Cornell University Press, 1984), p. 13.

[38] John Lewis Gaddis, ‘What Is Grand Strategy?’ American Grand Strategy After War’, 2009, p.7 as cited by Lukas Milevski, The Evolution of Modern Grand Strategic Thought (Oxford University Press, 2016), p.2.

[39] Echevarria, Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

[40] Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice, p. 28; Echevarria, Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition, p. 4.

[41] Joseph M. Guerra, “An Introduction to Clausewitzian Strategic Theory: General Theory, Strategy, and Their Relevance for Today,” Infinity Journal 2, no. 3 (2012), p. 31.

[42] Thomas M. Kane and David J. Lonsdale, Understanding Contemporary Strategy (Routledge Taylor&Francis Group, 2012), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203801512.

[43] Frans P B Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (Routledge Taylor&Francis Group, 2007), p. 11. http://www.tandfebooks.com/isbn/9780203088869.

[44] M.L.R. Smith and John Stone, “Explaining Strategic Theory,” Infinity Journal 1, no. 4 (2011): p. 30.

[45] Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 11.

[46] Echevarria, Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition, p. 4.

[47] “General Clark on the Iraq Invasion | American War Generals”, Youtube video, 2:59, “National Geopraphic”, 12 September 2014.

[48] Beatrice Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 5. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511762895.

[49] Colin S. Gray, The Future of Strategy (London: Polity Press, 2015), p. 28.

[50] Colin S. Gray, Theory of Strategy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 137.

[51] Rob Johnson, ‘The Changing Character of War: Making Strategy in the Early Twenty-First Century’, RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 6–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2017.1301489.

[52] Gray, Theory of Strategy, p. 146.

[53]. Robert Mihara, “Strategy: How to Make It Work,” Infinity Journal 3, no. 1 (2012): 20.

[54] Antulio J. Echevarria, Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction, Kindle Edition, p. 4.

[55] Gray, “Strategy: Some Notes for a User’s Guide”, p. 7.

[56] Hew Strachan, ‘Strategy in Theory; Strategy in Practice’, Journal of Strategic Studies 42:2, 2019, p. 190, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2018.1559153.

[57] Gray, “Strategy: Some Notes for a User’s Guide”, p. 6.

[58] Beatrice Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 18, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511762895.

[59] Emile Simpson, “Constitutional Stability versus Strategic Efficiency: Strategic Dialogue in Contemporary Conflict,” Infinity Journal 2, no. 4 (2012): p. 14.

[60] Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice, 138.

[61] Gray, “Strategy: Some Notes for a User’s Guide”, p. 5.

[62] Kane and Lonsdale, Understanding Contemporary Strategy.

[63] Gray, Theory of Strategy, p. 18.

[64] Strachan, The Direction of War, p. 29.

[65] Strachan, The Direction of War, p. 18; Lukas Milevski, “Strategy and the Intervening Concept of Operational Art,” Infinity Journal 4, no. 3 (2015): pp. 17–22.

[66]. Lukas Milevski, The Evolution of Modern Grand Strategic Thought (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 5, 18-19.

[67] Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, EricGrove (London: Annapolis, 1988), p. 30, as cited by Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective, p. 32.

[68] Lukas Milevski, “The Mythology of Grand Strategy,” Infinity Journal 3, no. 1 (2012): p. 29.

[69] Strachan, The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective, p. 34.

[70] Edward Mead Earle, Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to Hitler (Princeton University Press, 1943), p. viii, as cited by Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present, p. 26.

[71] André Beaufre, Strategy of Action (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), p. 29, as cited by Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present, p. 8.

[72] Gray, The Strategy Bridge, p. 28.

[73] Kane and Lonsdale, Understanding Contemporary Strategy, p. 14.

[74] Gray, The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice, p. 41-42.

[75] Avi Kober, ‘Nomology vs Historicism: Formative Factors in Modern Military Thought’, Defense Analysis 10, no. 3 (1994): 267–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/07430179408405629.

[76] Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 15.

[77] Azar Gat, The Origins of Military Thought : From the Enlightenment to Clausewitz, Oxford Historical Monographs, 1989, p. 252-53.

[78] Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 16.

[79] Clausewitz, On War, p. 13.

[80] Van Riper, “The Foundation of Strategic Thinking”, p. 6.

[81] Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present, p. 18.

[82] Echevarria, Clausewitz and Contemporary War, p. 56.