Increased tension over the past couple of years between West and Turkey has reached to another level after Turkey and Russia signed an accord for supplying S-400 surface-to-air missile batteries.

The S-400 deal, reportedly worth some $2.5 billion and according to Turkey’s Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (SSM) initial delivery planned for the first quarter of 2020.

The SSM said Turkey would buy two S-400 batteries from Russia under the agreement, with one being optional, and added the systems would be used and managed “independently” by Turkish personnel, rather than Russian advisors. As previously mentioned in various speeches by the Western officials and military experts, NATO member countries, who are already worried about Moscow’s military presence in the Middle East, are unnerved by this deal not only due to system’s incompatibility but also it significantly finances an opponent’s defense industry. However Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan has expressed that ties with NATO remain strong.

Although Turkey’s desperate and well-known need for a long-range missile defense system is understandable, it will still be difficult to explain the rationale behind the purchase of a Russian system in the current security landscape. From the military perspective, it should have two dimensions. Firstly, if Turkey would like to have a decent missile defense capability, there are definitely better options available in the market. Yet the missile defense capabilities of Russian systems are always ‘on paper’, it is difficult to tell that the system is ideally suited for Ballistic Missile Defense.

Range problem

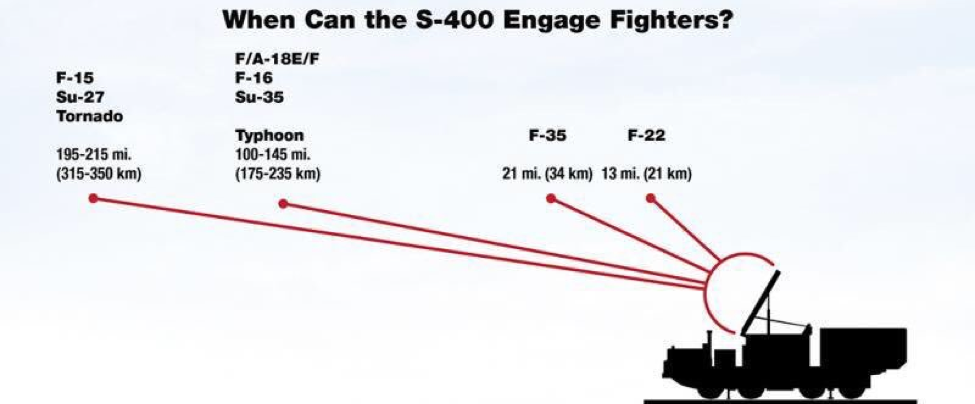

From the air-breathing target defense perspective; With its unrivaled maximum range of 400 kilometers, S-400 theoretically able to strike before the incoming aircraft enter the range of their anti-surface weapons. But when it comes to reality, the picture is different: the 400 km range missile is yet to be produced, and S-400 engagement envelope for ballistic missiles is less than 60 km. According to a study by Aviation Weekly, the actual engagement ranges for fighters are only a fraction of 400 km. Triumf (S-400) can engage an F-16 at 175-235 km, and an F-15 at 315-350 km, rendering those platforms almost unable to engage, but when it comes to low-observable (LO) aircraft, the name of the game changes. F-35 can only be engaged -if the numbers are precise- at 34km, easily enabling it to knock out an entire system with GBU-39 SDB. More than double in range with 72 to 108km, SDB munitions warrant F-35 a successful engagement. Turkey should go back to the drawing back and reassess gains and losses by obtaining this non-NATO system, acquisition of which is risking JSF delivery. The air and missile defense gap in Turkish airspace is wide, but sacrificing a prominent LO platform for S-400 is a trade that should be reassessed by Turkish defense acquisition planners.

Another real impediment from this deal would be the exclusion from NATO Air and Missile Defence. Currently, the crisis areas are closer to NATO territories. Therefore NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense (NIAMD) provide a clear solution to meet today’s priorities. NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense (NIAMD) is an essential, continuous mission in peacetime, crisis and times of conflict, which safeguards and protects Alliance territory, populations and forces against any air and missile threat and attack. It contributes to deterrence and indivisible security and freedom of action of the Alliance. NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense (NIAMD) ranges from NATO air policing in peacetime to the actions necessary to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of air and missile threats during times of crisis and conflict.

Integration problem

From NATO perspective, S-400 system will have no chance of being integrated into NATO BMD system. Turkish Defense Minister has already stated that the system will not be integrated to NATO and will operate independently. As a result, Turkey will not be able to take advantage of the European Phased Adaptive Approach’s (EPAA) sensor network.

Turkey is hosting a US BMD radar at Kürecik/Malatya, as part of the US European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA), which provides cueing data to all NATO-based missile defense systems. With the absence of NATO datalink, operators may be able to see the complete air picture with heritage systems but the system will not have access to the combat management software that cues the missile defense interceptors and there will be no automatic data transfer.

The primary goal of the air defense system is protecting the vulnerable sites of the country while preventing the enemy’s efforts to reach them. Principally, in order to have a robust air defense capability, different parts of the air defense network are expected to work harmoniously. Creating raw air picture, identification of targets, decision-making process, intervention and engagement are parts of this continuous process. Additionally, because every system has its strong sides and weaknesses, countries build their air defenses in a layered manner by various products, which complement each other. Area defense systems are complemented by point defense systems against close-in threats.

S-400 is a very complicated air and missile defense system. It has its own architecture. But it is still a single system.

In an operational environment, like Syria, Russia complements S-400 with different air defense capabilities. Air picture in Syria is most probably being produced by combining various sources like Syrian operational surveillance radars, Russian ground operating radars, Russian Navy’s eastern Mediterranean ships and other intelligence aircraft. These systems are supposedly compatible. Additionally, S-400 is also protected by SA-17 or SA-22 point defense systems against close-in threats like low altitude flying cruise missiles or UAVs. Furthermore, S-400 is additionally protected by electronic support systems which are transferred in Syria immediately after the transportation of S-400s.

Logistics has its different aspects, and everything is based on realities in logistics world. No single system can be operated continuously. Personnel training, spare parts and maintenance are also essential. Furthermore, for a sustainable air defense capability, logistics is very crucial.

Buying such a complex system will make Turkey heavily dependent on Russia for training & education, technical expertise and spare parts, which then, requires a stable and reliable bilateral relationship. Russian–Turkish relations have always been problematic from a historical perspective. Therefore, a possible conflict may result in severe repercussions in due course.

Just a short time after S-400 final deal, Turkey also engaged with MBDA for a study about missile defense. Heads of Eurosam and two Turkish Defense Firms (Aselsan and Roketsan) signed a Heads of Agreement (HoA) where it sets the work-sharing agreements for a definition study with the SSM on a long-range air and missile defense system to be launched in the coming months.

Albeit this deal seems only for the definition study, it still makes sense when one thinks about the narrow, inward focus for the S-400 procurement and its incapacity against Ballistic Missiles. Regardless, it seems that Turkey’s air and missile defense adventures will continue to attract international community for the foreseeable future.