Introduction

Belgium and the Netherlands governments are struggling to provide shelter to asylum seekers nowadays in addition to the displaced people from Ukraine. It turned out to be a ‘reception crisis’ leading to strikes, people sleeping on the streets and unhealthy conditions. The governments are trying to find short-term solutions. Given the global situation is leading to migration flows to Europe, longer term policy measures need to be taken at the EU and national levels to avoid such crises in the future.

|

KEY TAKEAWAYS

|

1. Background

Belgium has been facing saturation of its systems to receive asylum seekers for months now. Hundreds of people have to sleep on the streets because the doors of the Fedasil registration centre Klein Kasteeltje/Le Petit-Château in Brussels cannot handle providing shelter to the asylum seekers and the refugees which is their right to get.

In face of this situation, on August 18, State Secretary for Asylum and Migration, Nicole de Moor, tweeted: “What happened today at the Klein Kasteeltje cannot be repeated. The door must open, but we must be able to guarantee the safety of the staff and the other asylum seekers staying there.” Mayor of Brussels Philippe Close called on de Moor to tackle the problem and find a solution. Even though the Public Buildings Administration quickened plans to move the registration centre to Schaerbeek, the capacity of this centre is not competent in solving the problem.

1700 convictions have been opened against Fedasil, Belgium’s Federal Asylum agency, since October last year for failing to ensure its legal responsibility to shelter people. Fedasil staff went on strike on 23 August because of current running risky working conditions.

The current overwhelming problem results from certain facts such as the high rate of the occupancy of the asylum receiving centres and decreased capacity of those centres because the pandemic has brought the situation to a boiling point.

The neighbouring Netherlands is also facing the same problem. Hundreds of applicants of asylum are on the streets in front of Ter Apel’s asylum centre. Conditions are fragile and inhumane, especially for women and children. It was reported that a three-month-old baby died and an investigation was invoked by the House of Representatives. Besides, due to difficulties in taking showers, many of them have to deal with skin diseases. That is why Doctors Without Borders (MSF) are involved to offer medical assistance to people in need. It must be noted that it is the first time that Doctors Without Borders provide medical help in the Netherlands. MSF director for the Netherlands Judith Sargentini said that “Doctors without Borders has been around for fifty years, but it is the first time that we are offering emergency aid in the Netherlands. We are doing this because the Dutch government is so late, the conditions in which the people at Ter Apel find themselves are inhumane.” Sargentini also added that this is a short-term solution and it is important to consider a long-term solution.

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte emphasised that he was ashamed, and announced measures aiming to evacuate people from Ter Apel to get the overcrowding under control. But some asylum seekers refused to leave because they are afraid to lose their turn of registering and facing an obligation to restart the process again.

On 31 August, a cruise ship rented by the national government arrived in Amsterdam to provide accommodation for at least 1000 refugees. In addition, Utrecht reserved the majority of the social housing for refugees for six weeks. It should not be forgotten that there is a serious housing crisis in the Netherlands. Director of the Mixed Migration Center, Bram Frows stated: “There just aren’t enough houses in the country which affects the availability of houses for asylum seekers. So this means they will continue living in asylum reception centres across the country for months. In turn, the asylum centres have no capacity to receive new arrivals and people have to sleep outside.”

The European Union Agency for Asylum offers to provide 160 containers according to Operational Plan 2022 signed between the Dutch government and The European Union Agency for Asylum. The Dutch government is also planning to reduce family reunification to get the situation under control, which is criticised by the EU Commission spokesperson. “The government’s plan to handle this crisis by reducing family reunification arrivals in order to avoid congestion at Ter Apel should be avoided. So far, these people arrive on family reunification visas and also need to register at Ter Apel. There is no need for that since they have already been vetted. This isn’t a solution to stop overcrowding”.

2. Reception crisis in numbers

Belgium

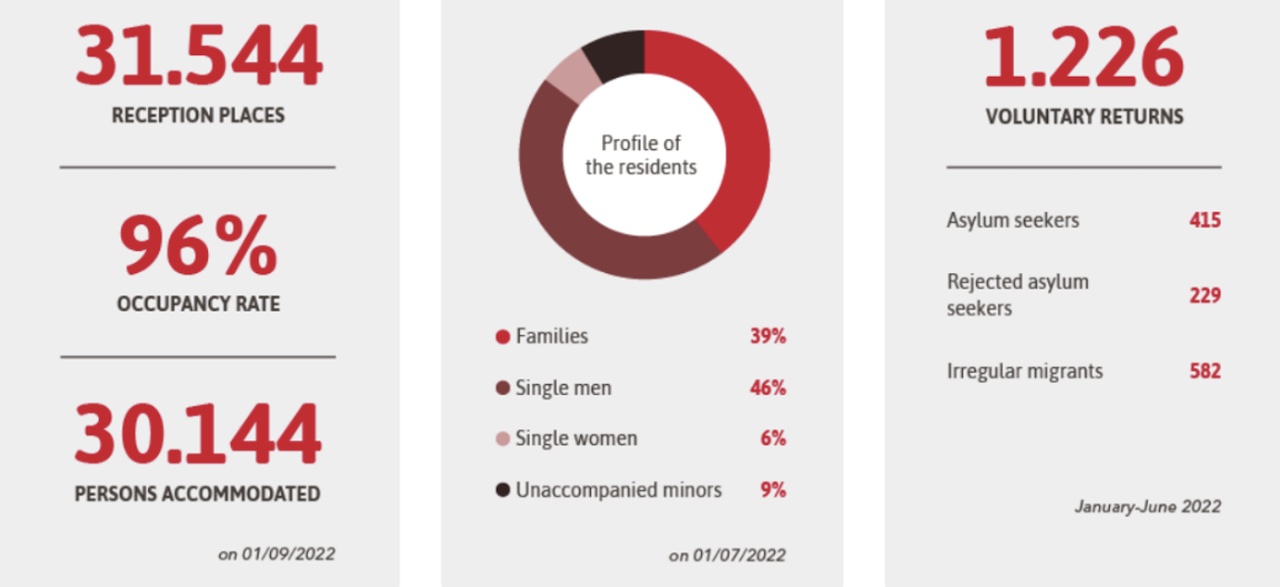

According to Fedasil statistics, Belgium has 32,544 reception places for asylum seekers, of which 30,144 are occupied as indicated in figure 2. These numbers do not include 55,598 temporary protection issued so far by Belgium for the displaced persons from Ukraine. Temporary protection is an exceptional measure to provide immediate and temporary protection in the event of a (imminent) mass influx of displaced persons from non-EU countries who are unable to return to their country of origin.

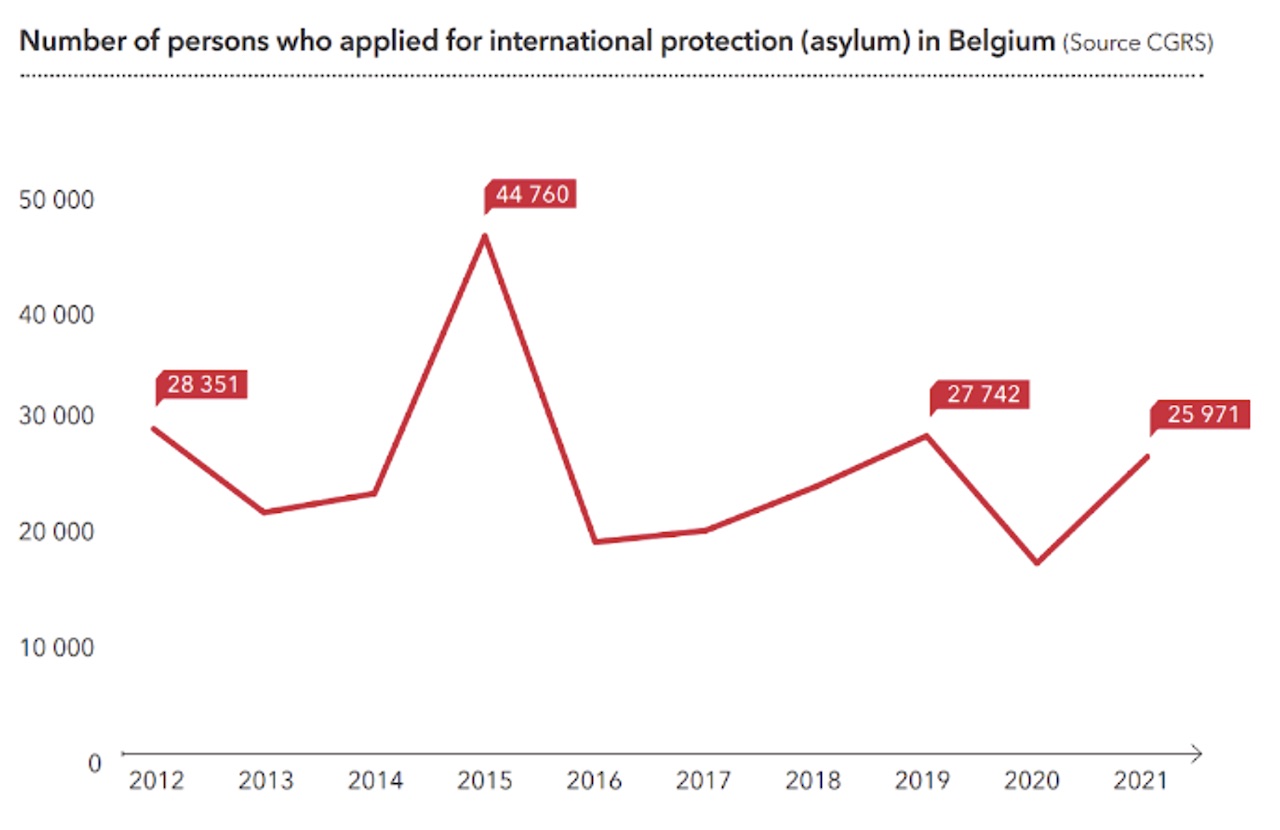

The asylum figures in Belgium saw a peak between 2014-2015, the years at which the civil war in Syria was especially intense (see figure 1). The exact figures for the year 2022 have not been published yet, however the sum of the asylum seekers and issued temporary protections has already passed the last year (figure 1,2). This unexpected increase is a result of a combination of geopolitical developments featuring Russian invasion of Ukraine at the beginning of 2022, Taliban’s takeover of rule in Afghanistan and the slow down of the pandemic.

Figure 1: Annual evolution of the number of persons who applied for international protection (asylum) in Belgium (FEDASIL)

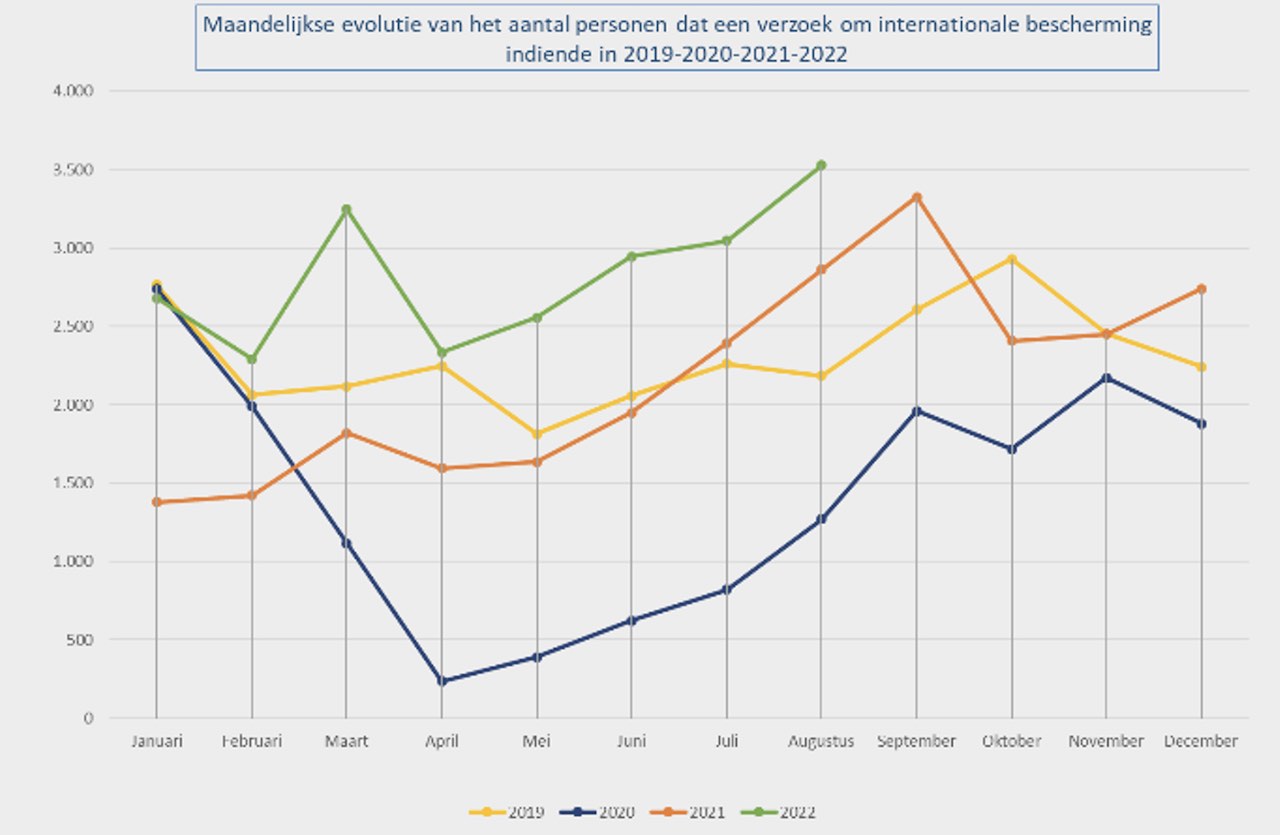

Figure 2: Monthly evolution of the number of persons who applied for international protection (asylum) in Belgium between 2019-2022 (CGVS)

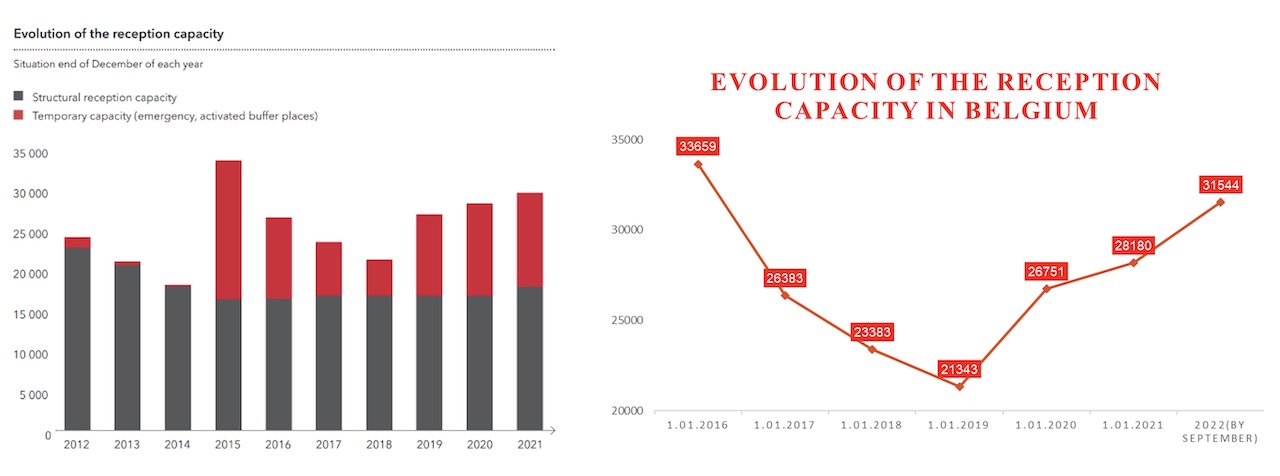

The evolution of the reception capacity indicates that the structural capacity has not been changed since 2015. However, the temporary capacity has been activated according to the needs. As of its peak point in 2015 (during the Syrian crisis) the total capacity decreased until 2018 and the capacity has been gradually increasing since then. The current occupancy rate is 96%.

Figure 3: Statistics of reception places and occupancy rate by September 2022 in Belgium (FEDASIL)

At the beginning of the Russian invasion, UNHCR estimated that approximately 200,000 Ukrainians would flee to Belgium. But The Federal Planning Bureau’s baseline scenario is a total influx of 83,000 refugees from Ukraine throughout 2022. To overcome this problem, the Belgium government assigned local authorities to accept Ukrainian refugees, giving them a subsidy of €2,000 – €3,500 (per refugee). Local authorities have created or assigned separate places for them to reside, such as temporary villages, and new reception centres. Additionally, they have coordinated the dispatch of the refugees with the support of NGOs to local families who are volunteering to host them in their houses.

Figure 4: Evolution of the reception capacity in Belgium (FEDASIL)

The Netherlands

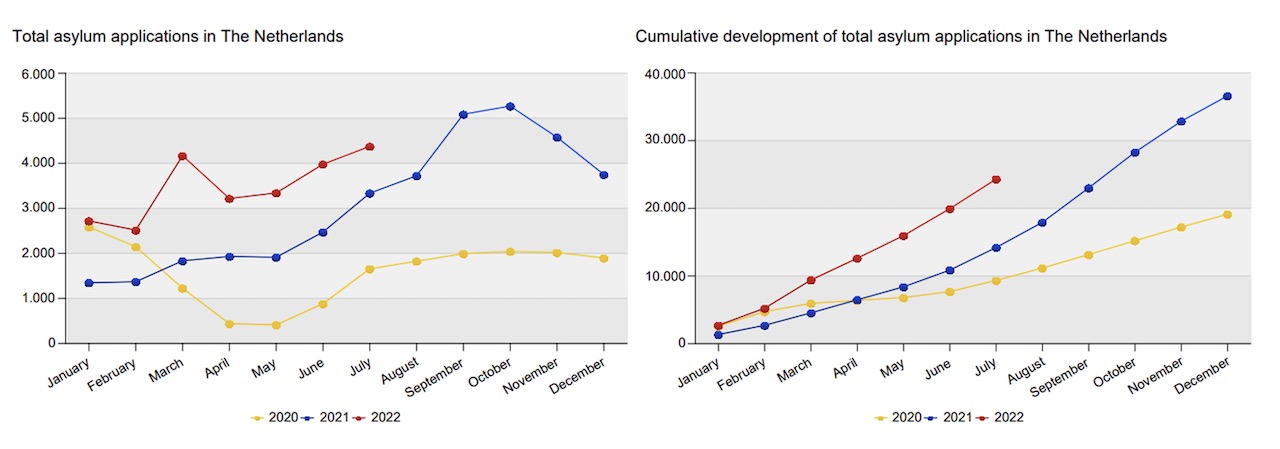

According to the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security, the total number of asylum applications in the Netherlands has reached 29,114 (not including Ukrainians) from January 2022 to August 2022. In the last 12 months, the number of applications counts up to 46,734, the biggest share or 41 percent of which come from Syrians.

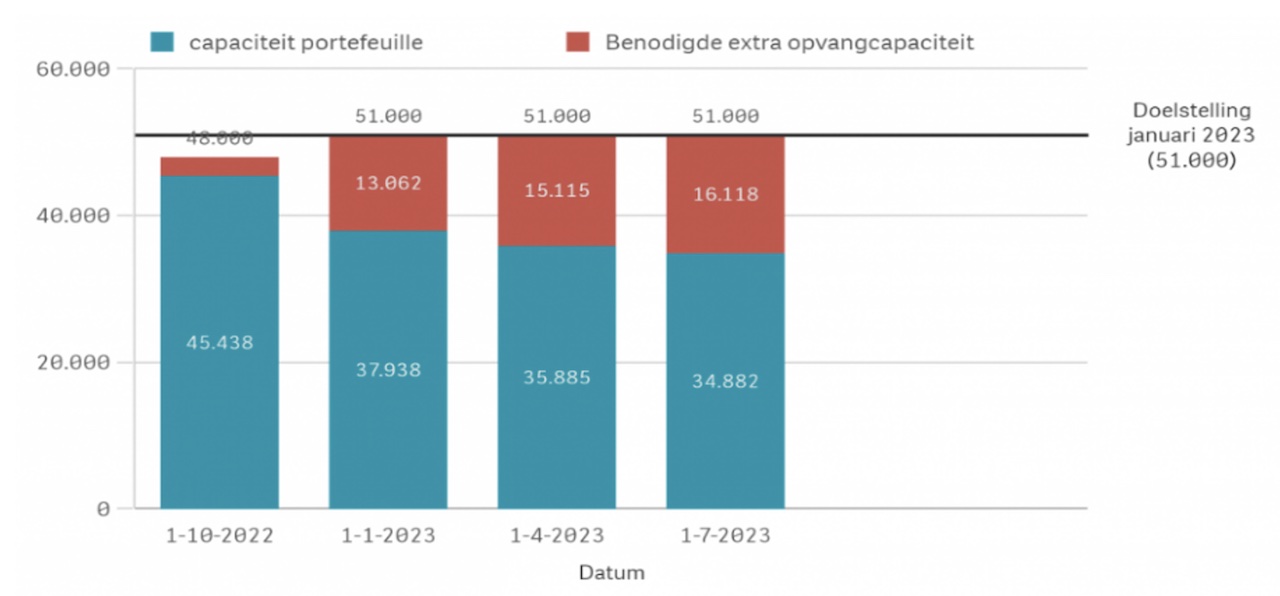

Figure 5: Capacity (real estate portfolio) versus capacity requirement (COA)

(The total locations does not include reception of Ukrainian refugees in municipal shelter Ukraine (GOO), reception of Afghan evacuees in defence locations, (crisis) emergency shelter managed by municipalities)

There is an increase in the total number of asylum applications (not including Ukrainians) by July compared to the last two years (see figure 6). The reasons behind are similar, the takeover of Taliban in Afghanistan and the pandemic’s slowdown. According to the Dutch Central Organisation for the reception of asylum seekers (COA), the Netherlands will require more than 13,000 additional reception capacity by 2023 .

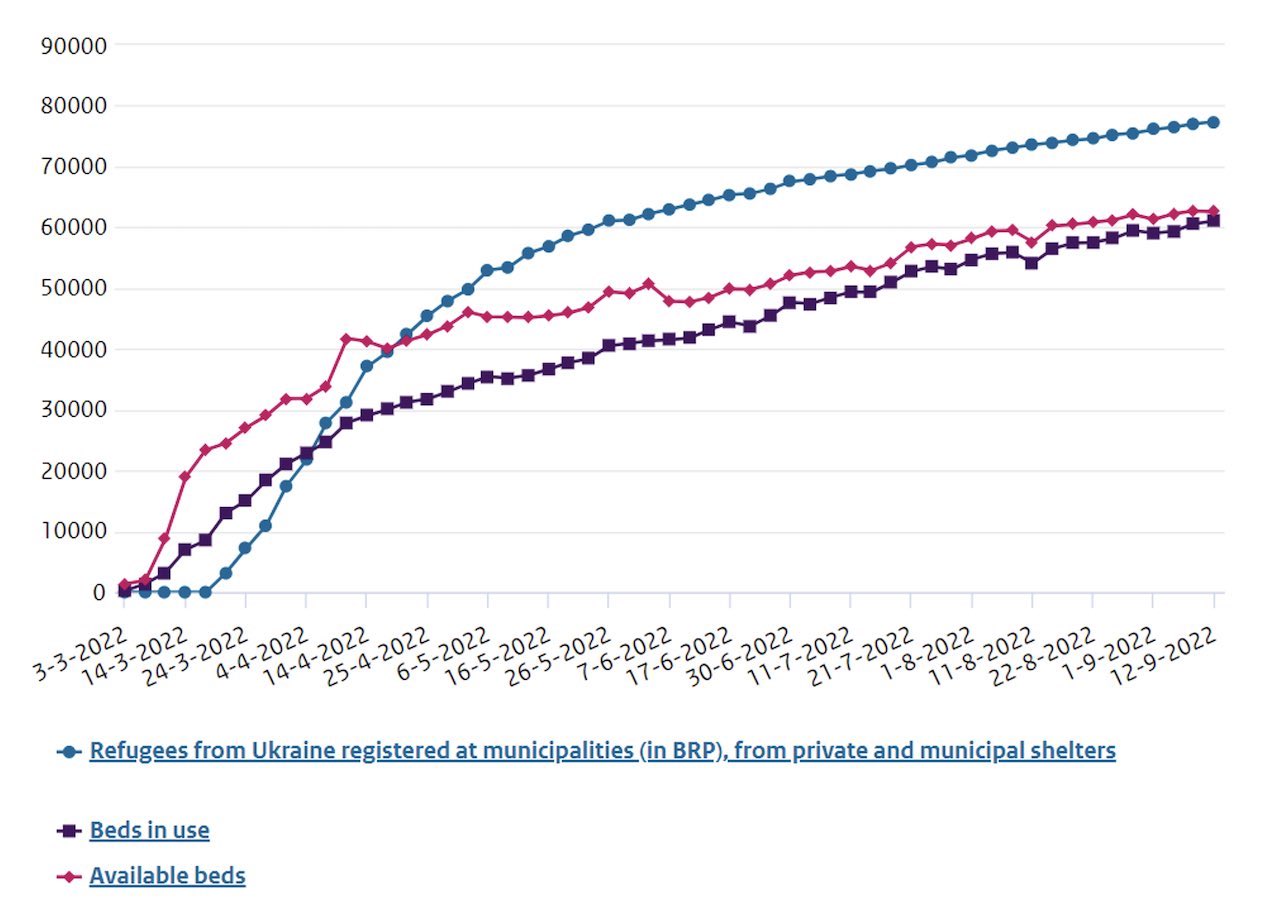

In addition to the asylum seekers, the number of refugees from Ukraine registered at municipalities, from private and municipal shelters stands at 76.470. Accordingly, 59.389 of 62.231 available beds are occupied. Ukrainians refugees are treated under the temporary protection statute as in Belgium. It is seen that there are more refugees from Ukraine than available beds (Figure 7), who are mostly hosted by volunteers or NGOs. At the beginning of the influx, thousands of Dutch families opened their houses to Ukrainians via some matching applications such as takecarebnb or Share My Home. But with the beginning of the summer, Dutch families started to leave their houses and they did not want to leave Ukrainians in their houses alone. So, many Ukrainians had to leave their hosting families putting a burden on municipalities to find additional accommodations.

Figure 6: Total asylum applications in The Netherlands and Cumulative development of total asylum applications in The Netherlands (Dutch Immigration Service)

Figure 7: Figures on reception of refugees from Ukraine in the Netherlands (Dutch Government)

3. What does it tell us?

There is a real ‘reception crisis’ both in Belgium and in the Netherlands. And it must be kept in mind that it is not an asylum crisis. It is more likely to be called a reception crisis, because the number of arrivals are lower than the levels in 2015. But still, the occupancy rates of reception centres in both countries are almost at their maximum capacity and the required additional reception capacity will likely increase by 2023 (see figures 4 and 5). So both countries must urgently seek to create extra places to increase the capacity in order to meet the requirements.

The structural problems are apparent at the political and policy level. Michael Kegels resigned from his position as Fedasil director, citing that “There are still so many challenges in the reception policy. All Fedasil employees work hard to give people a place to stay. In recent years, this task has become increasingly difficult.” On the other hand, Judith Sargentini, Dutch director of Doctors Without Borders, criticised the absence of political willingness of the Dutch government, noting that the Dutch government has not invested 200 million euros in the reception of refugees as was planned.

The politics of ‘reluctant reception’ at the national levels can be also seen as a significant factor. In line with that, the lack of a sufficient solidarity action among the EU member states regarding reception of asylum seekers is worsening the situation and making the crisis more unforeseeable for some of them.

It is hard to boil down the reasons for the ongoing crisis to purely lack of enough resources. It is undeniable there is a housing crisis, especially in the Netherlands. To respond to this problem, the plan of the Government is to build 100.000 additional capacity every year. But, there is shortage of workers and also a nitrogen emission crisis. The Netherlands has the second highest nitrogen surplus in Europe, which must be reduced by 2030. The nitrogen crisis and the shortage of workers together restrain the Netherlands from building houses as planned.

Experts have been proposing to keep a surplus reception capacity during times of lower arrivals, because it is cheaper to keep them open than build new ones when relatively higher numbers of migrants come. Besides, forcing small municipalities to host those arriving people is not a rational solution.

It must be noted that the “temporary protection” regime, which was introduced in 2001 after the Yugoslav War, has been used for the first time for displaced persons from Ukraine. The directive was urgently invoked on 4 March 2022 with a big solidarity among the member states right after the start of the illegal Russian occupation. It helped the EU to react in a very short time to the crisis although not in a perfect manner due to its shortcomings. However many member states were not prepared to implement the requirements of the directive. The great solidarity from the people and their volunteer support helped the governments to react. The member states need to have contingency plans for future cases of mass influx. The temporary protection should be handled in a way more proactive than reactive, imposing a minimum level of preparedness on the member states. A positive attitude within the society would not always be there. So the European and national level policies should be updated accordingly, given such cases are not out of scope in the foreseeable future.

The attention to the energy crisis has eclipsed this humanitarian crisis. And it is hard to say that migration towards Europe will decrease. The conflicts in the European periphery are far from being resolved. A wave of migration as a result of the climate crisis is on the door, and Europe is among the top list of destinations. So, a mixture of anticipation, preparation of the right policies and capacity building would help the Member States avoid similar crises.

On the other hand, providing more flexibility in asylum and integration policies could help the newly arrived to find jobs in a shorter period, leading to easier integration into society. As the Belgian Secretary of State Sammy Mahdi proposed in his action plan, partnership with organisations that are entitled to help recruitment may help asylum-seekers to find jobs in shorter periods. Tent Partnership for Refugees which is carrying its activities and network to Europe is a good practice that brings companies to pledge positions to refugees. This could accelerate the socio-economic integration of asylum-seekers while reducing economic and social pressure on governments. In addition, this could also help the newly arrived to find proper accommodation options and prevent over-concentration in urban areas.

References

Asylum and migration: The Netherlands also faces asylum crisis. (2022, August 21). The Brussels Times with Belga. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.brusselstimes.com/

Belgian municipalities will receive a subsidy for accepting asylum seekers. (2022, September 3). Belga News Agency. Retrieved September from https://www.belganewsagency.eu/

Belgium’s ‘Ukrainian villages’ open doors to refugees. (2022, May 12). DW. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.dw.com/

Boztas, S. (2022, August 31). First cruise ship for 1,000 refugees to come in Amsterdam. DutchNews.nl. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.dutchnews.nl/

CGVS (2022). Asielstatistieken Augustus 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 from https://www.cgvs.be/

Deux nouveaux centres d’accueil pour réfugiés ukrainiens à Molenbeek et Saint-Gilles. (2022, August 12). RTBF with Belga. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.rtbf.be/

European Commission (2022). Retrieved September 2022 from https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/

European Commission (2 March 2022). Ukraine: Commission proposes temporary protection for people fleeing war in Ukraine and guidelines for border checks. Retrieved September 2022 from https://ec.europa.eu/

FEDASIL (2022). Statistics. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.fedasil.be/

Fedasil est à la recherche d’un nouveau directeur général. (2022, September 6). RTBF. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.rtbf.be/

Fienet, V. (2022, May 9). Les réfugiés ukrainiens seraient bien moins nombreux que prévu à Bruxelles et en Belgique. RTBF. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.rtbf.be/

Frouws, B.(2022, September 22). Article & Podcast: MMC Director Bram Frouws, about the asylum reception crisis in the Netherlands. Mixed Migration. Retrieved September 2022 from https://mixedmigration.org/

Guerre en Ukraine : les familles d’accueil se disent satisfaites d’accueillir des réfugiés ukrainiens. (2022, September 7). RTBF. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.rtbf.be/

Halm, I.(2022, August 16). The Dutch nitrogen crisis shows what happens when policymakers fail to step up. Energy Monitor. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.energymonitor.ai/

Harbour V. & The Hague. (2022, May 6). Operational Plan 2022 Agreed by The European Union Agency For Asylum And The Netherlands. Retrieved September 2022 from https://euaa.europa.eu/

Immigration Office. (September, 2022). Retrieved September 2022 from https://dofi.ibz.be/

Lalor, A. (2022, May 10). Why is there a housing shortage in the Netherlands? The Dutch housing crisis explained. Dutc Review. Retrieved September 2022 from https://dutchreview.com/

Lyons, H. (2022, August 23). Staff at Belgium’s asylum reception centre stage spontaneous strike. The Bulletin. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.thebulletin.be/

Many Ukrainians must leave host families for shelters as summer vacation approaches. (2022, June 26). NL Times. Retrieved September 2022 from https://nltimes.nl/

Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid. (2022). Retrieved September 2022 from https://ind.nl/

Nazaruk, Z. (2022, March 9). Thousands open their homes to Ukrainian refugees. Dutch News. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.dutchnews.nl/

Norman, K. (2020). Reluctant Reception: Refugees, Migration and Governance in the Middle East and North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108900119

O’Leary, S. (2022, August 25). Three-month-old baby dies in overflowing Dutch asylum centre. Dutch Review. Retrieved September 2022 from https://dutchreview.com/

Panchana, E. (2022, August 25). Artsen Zonder Grenzen grijpt in bij asielzoekers in Nederland: ‘Bizar en beschamend’. DeMorgen. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.demorgen.be/

Perspectives démographique 2021-2070 – Update : nette révision à la hausse de la croissance de la population en 2022 suite à la guerre en Ukraine. (2022). Federaal Planbureau. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.plan.be/

Rijksoverheid. (2022). Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/

Shankar, P. (2022, September 1). Dutch asylum center disaster: Housing crisis and politics to blame for Ter Apel crisis. InfoMigrants. Retrieved September 2022 from http://www.infomigrants.net/

‘Situatie Ter Apel is mensonwaardig’: Artsen zonder Grenzen biedt voor het eerst medische hulp in Nederland. (2022, August 25). De Morgen. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.demorgen.be/

Staatssecretaris Sammy Mahdi stelt actieplan voor om asielzoekers aan het werk te krijgen. (2021, December 1). HLN. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.hln.be/

Temporary protection. (2022). European Commission. Retrieved September 2022 from https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/

24,000 Ukrainian refugees working in the Netherlands; Amsterdam & The Hague most popular. (2022, July 17). NL Times. Retrieved September 2022 from https://nltimes.nl/

Utrecht reserves virtually all social housing for settled refugees for six weeks. (2022, July 13). DutchNews.nl. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.dutchnews.nl/

Walker, L. (2022, August 19). “Cannot be repeated”: Migration Minister called on to find solution for migrant crisis. The Brussel Times. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.brusselstimes.com/